Branded with a hot iron, exiled, and later one of the most lucid political thinkers of his century, Cyrille Bissette was a major actor in the struggle against slavery in the French Empire. Yet his name remains largely erased from official narratives, eclipsed by a simplified memory of abolition. Retracing his path means understanding the complexity of Caribbean societies, the violence of the colonial system, and the intellectual power of a man who, long before 1848, had already thought freedom through.

Rehabilitating a name erased from imperial and republican history

History rarely remembers all of its protagonists. Some names impose themselves, sculpted by official narratives, while others gradually fade away, victims of an oblivion shaped by politics, rivalries, and selective memory. Cyrille Bissette, born in 1795 in Martinique, belongs to this second category. Yet he was one of the major actors in the fight against slavery in the French sphere: a founder of newspapers, a theorist of a new colonial policy, an indefatigable activist, and, for a time, a deputy.

His trajectory is a true journey through the colonial nineteenth century: a path marked by the violence of a defensive slave system, the internal divisions of Caribbean societies, the manufacture of political enemies, and the instrumentalization of memory. Understanding Bissette therefore means questioning not only the structure of colonial power but also the social fractures of Martinique and Guadeloupe, European abolitionist strategies, and the complex dynamics of the post-1848 period.

The Bissette paradox

Cyrille Bissette was born into a free family of color at the very moment when the French Antilles were emerging from revolutionary turmoil. The status of “free mulatto” or “free person of color” was deeply ambiguous. It granted certain privileges compared to enslaved people, but remained marked by a set of legal, social, and racial discriminations. Free people of color rarely had access to education, even more rarely to positions of power, and remained under close surveillance by colonial authorities.

The Bissette family nevertheless belonged to an enviable category: that of a relatively affluent elite of color, orbiting the influential white families of the colony. Young Cyrille thus grew up in a stratified society, where the plantation economy shaped the social order and racial hierarchies imposed themselves as an immutable dogma.

Around 1818, he became a merchant in Fort-Royal. This activity placed him at the heart of the colonial economic system, exposed him to its injustices, but also gave him a refined understanding of its internal functioning: commercial networks, the influence of planters, and total dependence on slavery. Like many affluent free people of color of the time, he navigated between economic collaboration and political frustration.

The founding moment of Bissette’s engagement came in 1823, when a pamphlet circulating clandestinely on the island—criticizing the status of free people of color and denouncing the slave order—was attributed to him and a few others. This text, which argued for civil equality, the end of corporal punishment inflicted on freed people, and the establishment of education for all, constituted a rare act of political defiance in the repressive colonial context.

The authorities’ reaction was immediate: searches, arrests, and then a trial designed as an example. Bissette was sentenced to a punishment of exceptional violence: branding with a hot iron bearing the inscription “GAL,” an infamizing mark reserved for the most harshly punished criminals. The public branding was conceived as a ritual of domination, reminding free people of color of their place in the colonial order and the dangers of any political claim.

Although his first conviction was overturned on appeal in Paris, the colony organized his expulsion. For Bissette, this violence was not merely a humiliation; it was a rupture. It marked the birth of a determined activist, convinced that emancipation could only come from a radically new intellectual and political mobilization.

Paris, the press, and political thought

In Paris, Bissette discovered a very different political landscape. Far from colonial authoritarianism, he found a space where the press, salons, Masonic lodges, and parliamentary circles allowed ideas to circulate and positions to be defended. He became familiar with European abolitionist networks but quickly distinguished himself through an original thought, deeply rooted in Caribbean reality.

It was in this context that he founded La Revue des colonies, a journal he would lead for more than a decade. A true political laboratory, the review analyzed laws, denounced injustices, examined the condition of freed people, and openly criticized slave ideology. Unlike metropolitan abolitionists, who often approached the empire in abstract terms, Bissette articulated a vision built from colonial experience: he knew “from the inside” the mechanisms of social violence, racial relations, and everyday forms of resistance.

His articles also included concrete proposals: a supervised transition, preparation of freed people for citizenship, reform of the plantation economy, and political dialogue among social groups. This pragmatic dimension, nourished by his precise knowledge of Caribbean society, made him a unique analyst of the period.

The abolition of slavery in 1848 profoundly disrupted the colonial order. For Bissette, who had spent twenty years denouncing oppression and proposing solutions, it was an ideological victory. When he returned to Martinique, he was welcomed by a newly freed population that saw him as one of the architects of its liberty.

He then undertook a large-scale political effort. Acknowledging that the island was emerging from a system founded on violence and segregation, he called for “forgetting the past” and rebuilding a shared social fabric. This fundamentally modern idea ran counter to the vengeful logic some feared. Bissette did not seek the brutal collapse of colonial society, but its gradual transformation through the political, economic, and cultural integration of former slaves.

In 1849, he was elected deputy. His election represented a powerful symbol: a former free man of color, branded with a hot iron and condemned by the slave system, became one of the representatives of the new citizenship.

But the victory was short-lived. Political rivalries, the mistrust of part of the free population of color, tensions with certain metropolitan abolitionists, and maneuvers orchestrated by his adversaries weakened his position. A sense of betrayal arose among some groups when he allied, in order to stabilize the political landscape, with white figures from the former colonial elite. This pragmatic strategy was perceived by some as a compromise.

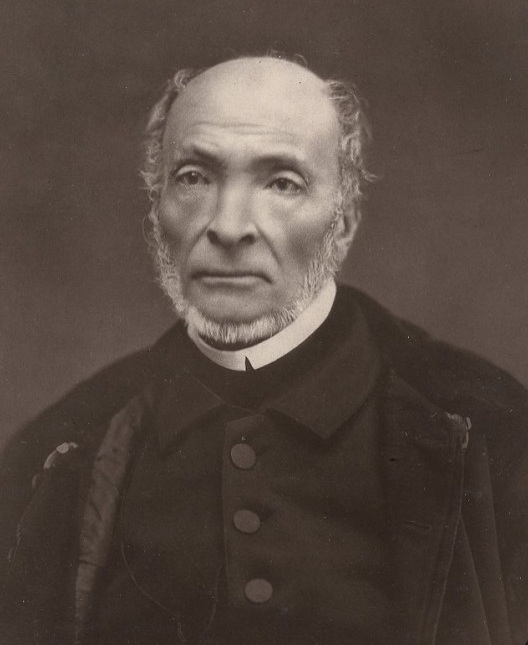

Victor Schœlcher photographed by Étienne Carjat.

One of the most complex dimensions of Cyrille Bissette’s history is his rivalry with Victor Schœlcher.

The two men did not share the same vision of post-slavery society, nor the same conception of the role of the state. One, shaped by colonial society and deeply rooted in Caribbean realities, thought in terms of internal balances. The other, a European abolitionist, inscribed emancipation within a universalist narrative centered on the intervention of the Republic.

After 1848, part of the French press and political class chose to construct a memory of abolition centered on a single figure. In this process, Bissette became “the man to erase.” His work received little attention, his writings were marginalized, his political conflicts were magnified, and his stature deliberately diminished. Opposite him, a heroic narrative was built around one name, facilitating the construction of a coherent national memory—but one that was historically reductive.

This marginalization partly explains why, even today, Bissette remains less well known than other abolitionists, despite his substantial role.

After the coup d’état of 1851, Bissette gradually withdrew from political life. The climate was no longer favorable to dissident voices, and the Second Republic, sliding toward increasing authoritarianism, left little room for anticolonial activists.

He nevertheless continued to write, publish, and observe. But his influence waned, networks contracted, and the generation that followed retained above all the simplified version of abolition disseminated by the Republic.

Martinique itself preserves an ambivalent memory of Bissette: some institutions honor him, while others prefer to forget his positions, alliances, or divergences with local elites. His legacy remains fragmented, sometimes contested, often misunderstood.

History readily retains simple, univocal figures that are easy to celebrate. Bissette is the opposite. He embodies nuance, complexity, political ambiguity, and strategic compromise.

He is neither a radical revolutionary nor a conservative; neither a blind assimilationist nor an uncompromising separatist. His thought escapes the categories into which Afro-diasporic actors of the nineteenth century are often confined.

Above all, he unsettles because he reminds us that abolition was a collective endeavor: the work of Black men and women, free or enslaved, of activists, journalists, insurgents, and political thinkers. The idea of an abolition “granted” by a single individual does not withstand historical analysis.

Bissette makes this truth impossible to ignore.

Today, Bissette’s contribution resonates powerfully in debates on memory, social justice, Caribbean identity, and postcolonial politics.

He anticipates several essential dimensions of the modern Afro-diasporic struggle:

- The importance of the press and intellectual production in political struggle.

- The demand for universal civil rights, transcending the racial question without ignoring it.

- The necessity of thinking about “after,” that is, the construction of a new society following the fall of an oppressive system.

- The articulation between memory and action, where understanding the past becomes a tool of emancipation.

At a time when many states are reassessing their historical narratives, Cyrille Bissette emerges as an essential figure: a man who did not wait for republican legality to demand justice.

Cyrille Bissette embodies a rare form of political courage. His life bears witness to the violence of the slave system, but also to the determination of those who, from within the colonies themselves, imagined a future without chains.

Rehabilitating his name is not an act of militancy; it is a requirement of historical truth. For the history of abolition cannot be understood without its multiple voices, its contradictions, its tensions, and without the major contribution of men like him.

For NOFI.media, telling the story of Cyrille Bissette is to affirm that Afro-diasporic worlds possess their own thinkers, their own strategists, their own architects of freedom. It is to remind us that emancipation was never a gift: it was conquered, thought, written, and contested—sometimes at the price of a red-hot iron.

Notes & References

- Arlette Gautier, Les sœurs de Solitude. La condition féminine dans l’esclavage aux Antilles, Paris, Éditions La Découverte, 1985.

- Frédéric Régent, La France et ses esclaves. De la colonisation aux abolitions, 1620–1848, Paris, Grasset, 2007.

- Frédéric Régent, Esclavage, métissage, liberté. La Révolution française en Guadeloupe, Paris, Grasset, 2004.

- Laurent Dubois, A Colony of Citizens: Revolution and Slave Emancipation in the French Caribbean, 1787–1804, University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Myriam Cottias, La question noire. Histoire d’une construction coloniale, Paris, Bayard, 2007.

- Myriam Cottias (ed.), Dictionnaire des esclavages, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2018.