Ottobah Cugoano, a former African slave who became an intellectual in London, was one of the earliest Black voices of British abolitionism in the eighteenth century.

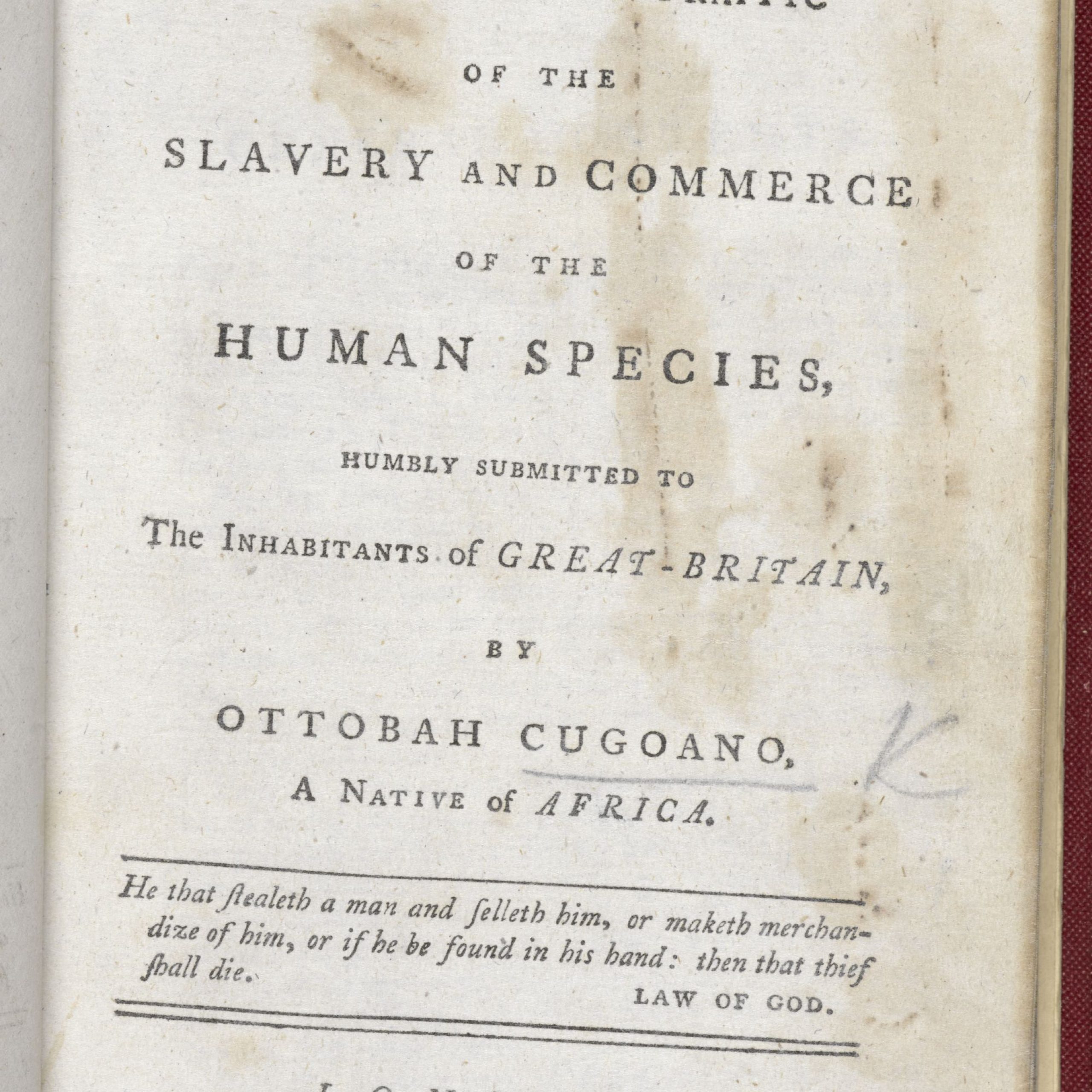

At the heart of London in the 1780s, while the British Empire derived a crucial share of its wealth from Atlantic trade and the exploitation of enslaved labor, a voice rose with unusual clarity. This voice was neither that of a parliamentarian, nor that of an influential pastor, nor even that of an Enlightenment philosopher. It was the voice of Ottobah Cugoano, an African born on the Gold Coast, a former slave who became an author and abolitionist activist. In 1787, his book Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species formulated one of the most radical and earliest critiques of Atlantic slavery.

Long relegated to the margins of European intellectual history, Cugoano now appears as a central figure in abolitionist thought, bearing an autonomous African voice in a debate dominated by white British elites.

The abolitionist thought of Ottobah Cugoano in eighteenth-century England

Ottobah Cugoano was born around 1757 in Ajumako, in the hinterland of the Gold Coast, a region corresponding to present-day Ghana. He belonged to a Fante family relatively well integrated into local political structures. Contrary to a reductive vision of a precolonial Africa as chaotic or outside of history, the world in which Cugoano grew up was structured by political authorities, social hierarchies, and long-established commercial networks. Fante societies participated in complex regional exchanges well before the intensification of the Atlantic slave trade.

However, in the mid-eighteenth century, the growing pressure of the European slave trade disrupted these balances. Coastal forts, local intermediaries, and transatlantic demand contributed to an increase in raids and kidnappings, often far from areas directly controlled by Europeans. It is within this specific context, and not within an abstraction called “Africa,” that Cugoano’s childhood must be situated.

Around the age of thirteen, Cugoano was kidnapped along with other children. He was taken to Cape Coast and then forcibly embarked on a slave ship bound for Grenada in the British West Indies. This crossing and the years that followed constituted a formative experience, which he would later describe with chilling restraint. On the plantations, he discovered the economic logic of slavery, in which human beings were reduced to interchangeable units of value.

In his book, he recalls having been appraised at the equivalent of a few European manufactured goods, a brutal reminder of the dehumanization at the heart of the slave system. These passages, although subjective, constitute precious sources, as they articulate lived experience with a moral and political analysis. Historians nonetheless stress the need to read them as testimonies constructed after the fact, written in a militant context, without denying their fundamental truthfulness.

Cugoano’s trajectory shifted in 1772, when he was purchased by Alexander Campbell, a Scottish merchant, who brought him to England. London was not at that time a haven of freedom for Africans, but the legal framework there was ambiguous. That same year, the Somerset v. Stewart case called into question the legality of slavery on English soil, without formally abolishing it.

Cugoano managed to obtain his freedom in this climate of legal uncertainty. He learned to read and write, converted to Christianity, and was baptized in 1773 under the name John Stuart at St James’s Church, Piccadilly. Access to literacy played a decisive role in his transformation. It was not merely a personal emancipation, but the acquisition of a tool that allowed him to formulate a structured critique of the system that had enslaved him. As historian Anthony Bogues would later note, writing became for Cugoano a space for the reconquest of political subjectivity.

From the 1780s onward, Cugoano became integrated into a network of literate Africans and Afro-descendants living in London. He worked as a servant in the household of artists Richard and Maria Cosway, which allowed him to frequent influential intellectual and artistic circles. Above all, he joined the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group composed of free Black men, among whom was Olaudah Equiano. Contrary to a paternalistic vision of abolitionism, these Africans were not merely witnesses instrumentalized by white reformers. They wrote to newspapers, addressed petitions, and intervened directly in legal cases.

In 1786, Cugoano played a key role in the rescue of Henry Demane, a Black man kidnapped and destined to be forcibly returned to the West Indies. By alerting the abolitionist Granville Sharp, he helped secure Demane’s release before the ship’s departure. This episode illustrates the passage from written advocacy to concrete political action.

It was in this context that Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species appeared in 1787. The book stands out for its radicalism. Where many British abolitionists argued for gradual abolition or focused on the slave trade rather than the institution itself, Cugoano demanded the immediate abolition of slavery and the unconditional emancipation of those held in bondage. His argument rests on three pillars. The first is theological. A committed Christian, he asserted that slavery was incompatible with the teachings of Christ and constituted a direct offense against divine law.

The second pillar is political. He argued that slavery corrupted the societies that practiced it, generated violence and instability, and contradicted the principles of liberty that Britain claimed to defend. The third is moral and legal. Cugoano went so far as to justify the right of enslaved people to free themselves by force, an extremely bold position for the time. This assertion, often softened in later accounts, places his text at the boundary between philosophical reflection and a call to action.

The reception of the book was mixed. It went through several editions and was translated into French, a sign of a certain resonance within abolitionist circles. Artistic and intellectual figures supported its dissemination. However, its political influence remained limited. In a context marked by deep structural racism, the voice of an African, even a free and educated one, struggled to assert itself against the white voices of the abolitionist movement. Historian Adam Dahl emphasizes that Cugoano’s radicalism, particularly his refusal of any gradualism, placed him on the margins of a more cautious reformist consensus. This marginalization helps explain why his name quickly disappeared from dominant narratives of British abolitionism.

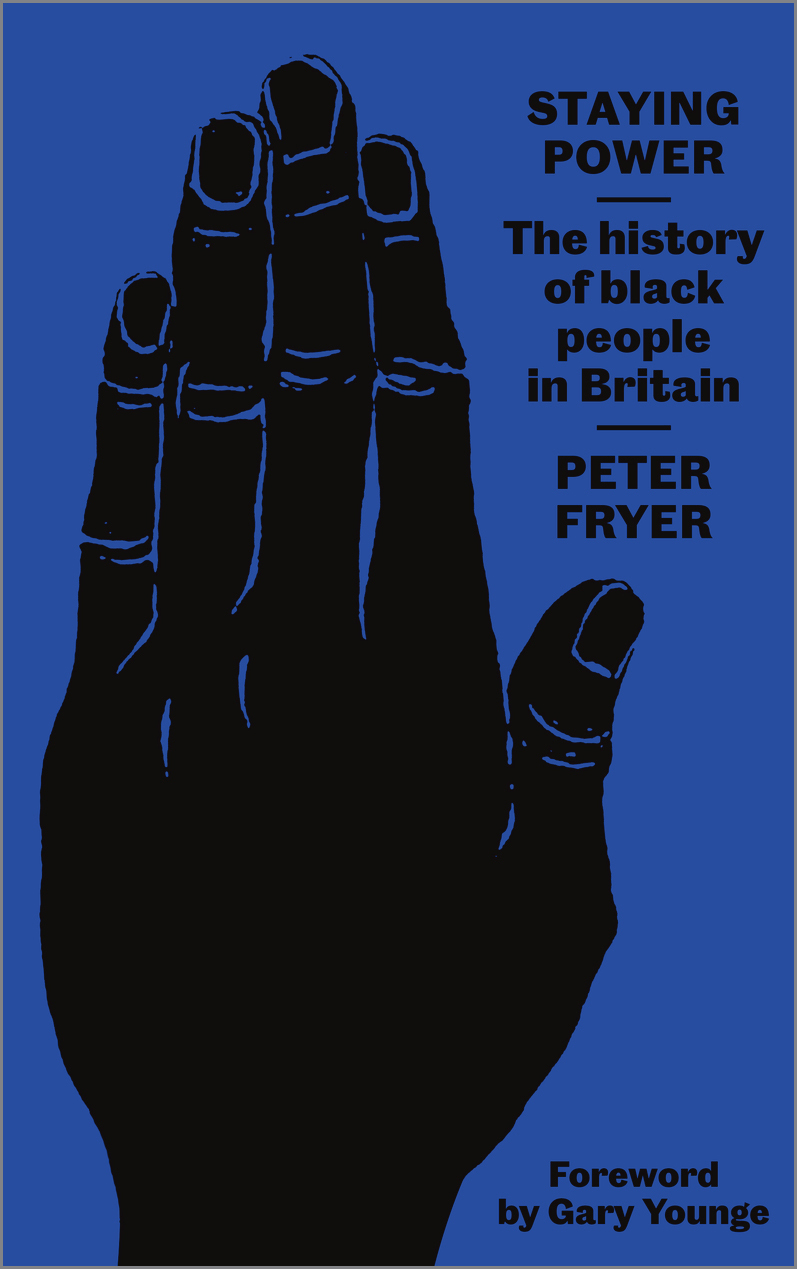

After 1791, Cugoano fades from the archives. His last letters mention travels intended to promote his book and defend the abolitionist cause. The exact circumstances of his death remain unknown, probably occurring in the early 1790s. This disappearance is not incidental. It reflects a selective construction of historical memory, in which African figures are often relegated to the background in favor of European reformers deemed more acceptable. As Peter Fryer showed in Staying Power, the history of Black people in Britain is marked by these silences and organized omissions.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, Ottobah Cugoano has been the subject of a gradual rediscovery. In 2020, an English Heritage commemorative plaque was placed on the house where he lived in London. In 2023, St James’s Church, Piccadilly commemorated the 250th anniversary of his baptism, accompanied by a specific artistic commission. These initiatives are part of a broader movement to recognize Black British history. They do not constitute a belated rehabilitation, but a necessary reintegration into a historical narrative long distorted.

Ottobah Cugoano is neither an isolated figure nor a mere witness to slavery. He is an African intellectual of the Atlantic world, capable of thinking about his era with remarkable clarity. His trajectory reminds us that abolitionism was not solely the product of a European awakening of conscience, but the result of multiple interventions, including those of African men and women who transformed their experience of oppression into political argument. Writing the history of abolition with Cugoano, and not simply about him, makes it possible to restore the full complexity of a struggle in which African voices were, from the outset, a driving force.

Notes and references

Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, London, 1787.

Anthony Bogues, Black Heretics, Black Prophets: Radical Political Intellectuals, Routledge, 2003.

Adam Dahl, “Creolizing Natural Liberty: Transnational Obligation in the Thought of Ottobah Cugoano,” The Journal of Politics, 2019.

Peter Fryer, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, Pluto Press, 1984.

English Heritage, “Ottobah Cugoano Blue Plaque,” 2020.

BBC News, “Quobna Cugoano: London church honours Ghanaian-born freed slave and abolitionist,” September 20, 2023.

Table of contents

The abolitionist thought of Ottobah Cugoano in eighteenth-century England

Notes and references