On 22 september 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed the Empire of Haiti. A few weeks later, he crowned himself Jacques I in Cap-Haïtien. The first Black Empire in the Americas, the experiment lasted only two years: iron constitution, bloody campaign in 1805, and assassination in 1806. But in two years, Dessalines fixed the horizon of a State: transforming conquered freedom into a fortress against the return of the colonial yoke.

Cap-Haïtien, the imperial dawn

October 1804. In the dense heat of Cap-Haïtien, the former enslaved people turned soldiers witness a ceremony unprecedented in the Americas. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, hero of the war of independence, crowns himself emperor under the name Jacques I. Draped in purple, haloed by victory over the Napoleonic army, he proclaims to the world the existence of a sovereign Black Empire. The echo is immense: for the first time, a nation born of a slave uprising claims an imperial order, both mirror and challenge to European monarchies.

But behind the pageantry, a reality imposes itself: Haiti, born in blood, must survive in a hostile world. Napoleon has not given up, the United States hesitates, Spain still controls the eastern part of the island, and the young nation is exhausted. Dessalines chooses Empire: an authoritarian, military, centralized political form, meant to protect the freedom that has been won. Two years later, he is assassinated at Pont-Rouge, leaving behind a fractured State but lasting foundations.

How should this First Empire of Haiti be understood? Was it a simple bloody Caesarism, or a pragmatic attempt to set up a barrier against recolonization and economic dependence? To answer, one must return to the revolutionary legacy, the institutions of 1805, the bloody Santo-Domingo campaign, the economic choices and the brutal fall of Jacques I.

The independence of 1 january 1804 did not end the state of permanent siege. The memory of the massacres of 1802–1803, of Rochambeau and the threats of French reconquest, haunted the island. Dessalines, governor-general proclaimed in Gonaïves, knew that a fragile republic would not survive. He needed a form of power able to mobilize the army, discipline the population and instill fear in the enemy.

The choice fell on Empire. Unlike European monarchies, the crown was not dynastic but elective: the emperor named his successor. This formula aimed to avoid succession wars while keeping the iron hand of a military chief. The motto “Liberty or death” became the State motto, and the imperial arms integrated cannons, drums and palm trees.

This was no coincidence: the Empire was born from war and for war. In an island still smoking from battle, the sabre and the land were the only sources of legitimacy.

The Constitution of 20 may 1805 fixed the framework of the Empire. It is a brief, military text, without republican lyricism.

Haiti was divided into six military divisions, each commanded by a general directly subordinated to the emperor. The civil hierarchy disappeared in favour of the military chain. Sovereignty did not belong to the abstract people, but to the emperor, “father of the nation”.

The crown was declared elective and for life: Jacques I designated his successor. This clause, inspired both by the Roman Empire and by African kingdoms, aimed to lock down power.

But it is above all on the racial and land question that the Constitution innovates: no White person could own land or exercise mastery in Haiti. The only ones tolerated were the Germans and Poles who had fought alongside the insurgents. This provision, born from the traumatic experience of slavery, made colour a line of political defense. Haiti thus became the first modern State to proclaim universal equality… while excluding those who embodied the old colonial order.

The text made French the official language and recognized Catholicism as the dominant religion, but without an independent clergy: the State controlled everything.

In sum, the Constitution of 1805 forged a steel State, designed for survival, not for political liberty.

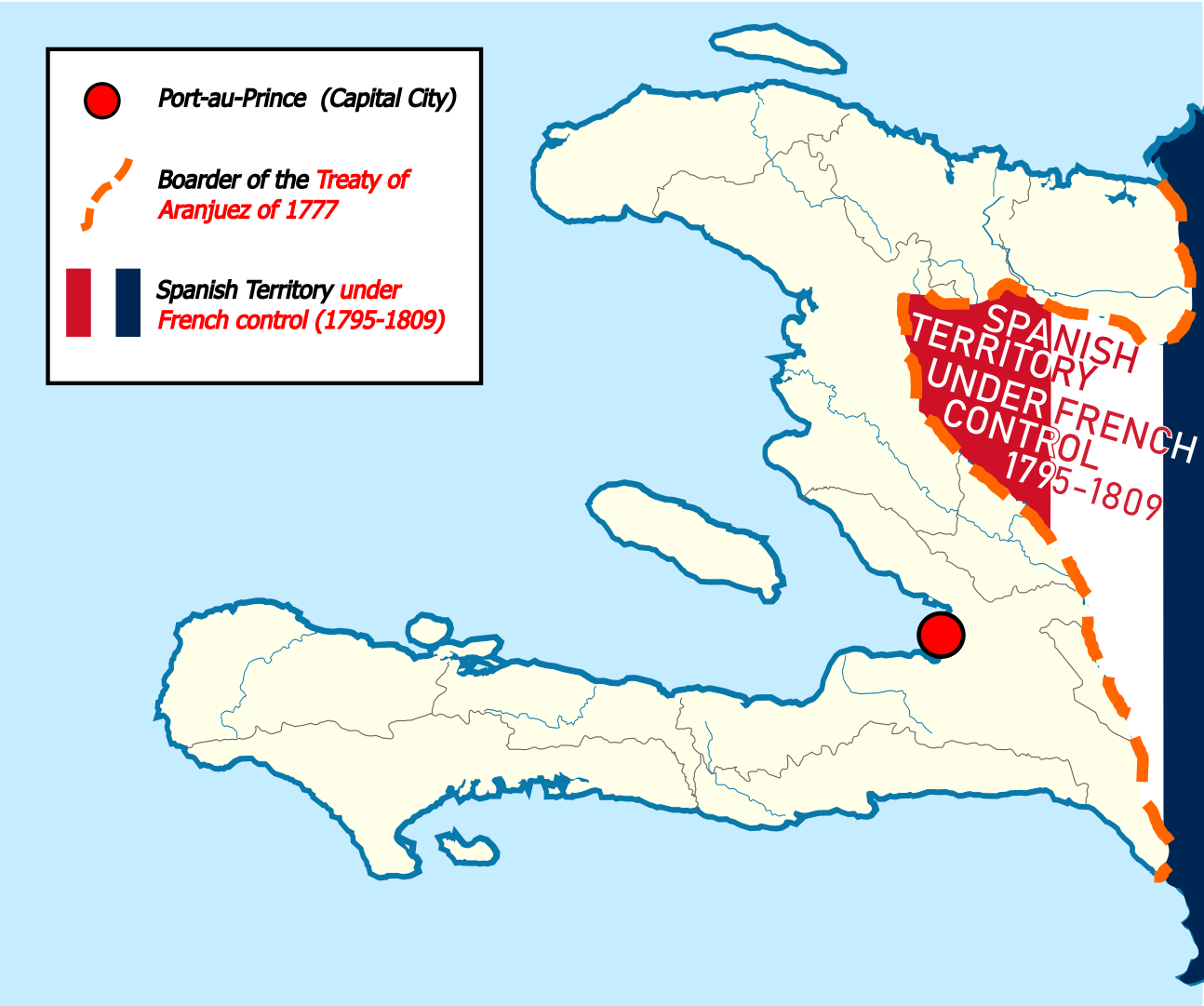

In 1804, the Empire of Haiti occupied only the western side of the island. In the east, Santo-Domingo remained under French control before being taken back by Spain in 1809. Dessalines knew that this border was a permanent threat.

He then launched a policy of fortifications. The heights were studded with forts and redoubts, the passages closely watched. Cap-Haïtien and Port-au-Prince became armed strongholds. In the logic of Jacques I, every peasant had to be a potential soldier, every field a reserve for the army.

Imperial geopolitics rested on a certainty: Haiti would survive only if it discouraged any attempt at reconquest through total militarization.

At the beginning of 1805, Dessalines decided to put an end to the eastern threat. He launched an offensive in two columns. In the north, Christophe took Santiago and advanced to La Vega. In the south, the emperor marched on Hinche, San Juan and Azua. The Haitian troops reached Santo-Domingo and besieged the city.

But a French squadron arrived as reinforcements. The siege was lifted. Then began a bloody retreat. Haitian troops burned towns and villages, massacred inhabitants of Santiago, Moca, La Vega, Baní. The logic was clear: punish a population perceived as hostile and discourage any collusion with the French.

These events left a deep mark on Dominican memory and fed the centuries-long hostility between the two peoples. For Haiti, the 1805 campaign was both a warning sent to European powers and a demonstration of brutality that shocked contemporaries.

On 20 may 1805, in the wake of this campaign, Dessalines adopted a new black and red flag, symbol of mourning and blood. This flag, later adopted by Christophe and Duvalier, became the emblem of a radically Black power.

Independence did not mean prosperity. The island was devastated, infrastructures destroyed, foreign markets closed. The Empire’s economy rested on three pillars: land, labour and the army.

The lands of the French colonists were confiscated. Some were distributed to officers to ensure their loyalty. The rest was exploited through a system of forced labour. Each peasant was assigned to a plantation; the State imposed quotas and discipline. This regime, harsher than that of Toussaint Louverture, provoked resistance. But for Dessalines, it was a necessity: without agricultural production, no revenue; without revenue, no army.

The logic was implacable: the economy was subordinated to war. The imperial treasury was built on sugar, coffee and forced export.

Dessalines staged his power. He adopted imperial attributes: mantle, sceptre, ceremonial. A military nobility formed around him. Generals became counts and dukes, officers received lands and titles.

But this staging had a political function: embodying Black sovereignty in the face of Europe. The coronation of Jacques I, far from being a personal fantasy, was a message sent to the world: the former enslaved would not settle for a fragile republic, they positioned themselves as equals of kings and emperors.

In society, however, tensions persisted. Administration was conducted in French, but the people lived in Creole. The distance between military elites and peasants widened. The imperial order appeared as a confiscation of the freedom that had been won.

Barely two years after his coronation, Dessalines was betrayed by his own. Christophe in the North, Pétion and Boyer in the West, all feared his brutality and his will to centralize.

On 17 october 1806, at Pont-Rouge, near Port-au-Prince, the emperor fell into an ambush. Riddled with bullets, his body was mutilated. The man who had defeated Napoleon was assassinated by his own.

The death of Jacques I plunged the island into division. The North, under Christophe, became a kingdom. The South, under Pétion, a republic. Haiti fractured durably.

The Empire of Dessalines lasted only two years. But it left a lasting imprint.

Politically, it gave Haiti a centralized, military State structure capable of resisting external threats. Economically, it imposed a discipline of iron, which guaranteed exportation at the price of peasant freedom.

Symbolically, it established the codes of Black sovereignty: the flag, the motto, the exclusion of Whites from land ownership.

Finally, it created an imaginary: that of a people who, to survive, accepted the authority of a war leader. This imaginary would resurface with Henri Christophe in the North, with Soulouque in 1849, with Duvalier in the 20th century.

Two years to shape a century

The First Empire of Haiti was brief, brutal, contradictory. But it was necessary. Without militarization, Haiti would likely have succumbed. Without the exclusion of Whites, recolonization would have threatened. Without economic discipline, the army would have collapsed.

Dessalines, Jacques I, embodied this logic: the freedom wrested had to be defended with the sabre, at the price of constraint and terror.

In two years, he set the lines of force that would run through the entire 19th century in Haiti: military centralization, North–South fracture, ambivalence between freedom and order.

The Empire fell with him, but Haiti itself remained standing.

Notes and references

Constitution impériale de 1805 – Official text of 20 may 1805, Archives nationales d’Haïti (ANH).

Proclamation de l’Empire – Act of 22 september 1804 and coronation in Cap-Haïtien in early october 1804, reported in contemporary Gazettes and in the edition by Thomas Madiou.

Madiou, Thomas – Histoire d’Haïti, Tome III, Port-au-Prince, 1847.

Saint-Rémy, Joseph – Mémoires de Toussaint Louverture suivis de sa correspondance, Paris, 1850.

Schœlcher, Victor – Vie de Toussaint Louverture, Paris, 1889.

Beaubrun Ardouin – Études sur l’histoire d’Haïti, Paris, 1853, vol. 9–10.

James, C.L.R. – The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage, 1963.

Hazareesingh, Sudhir – Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020.

Geggus, David – Haitian Revolutionary Studies, Indiana University Press, 2002.

Bell, Madison Smartt – Toussaint Louverture: A Biography, Pantheon, 2007.

Casimir, Jean – La culture opprimée, Port-au-Prince, 2001.

Moïse, Claude – Constitution et lutte de pouvoir en Haïti (1801–1806), Port-au-Prince, 1990.

Debien, Gabriel – Les colons de Saint-Domingue et la Révolution (1789–1795), Karthala, 1992.

Nicholls, David – From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race, Colour and National Independence in Haiti, Rutgers University Press, 1979.

Ardouin, Beaubrun – Guerre de l’indépendance de Saint-Domingue (1802–1803), Paris, 1853.

Summary

Cap-Haïtien, the imperial dawn

Two years to shape a century

Notes and references