Often reduced to the image of nomadic herders—or, more recently, confined to the security-driven caricatures of the Sahel—the Fulani nonetheless rank among the most structurally influential peoples in African history. From their great pastoral migrations to the founding of powerful Islamic states, from colonization to contemporary crises, their trajectory sheds light on the deep tensions between mobility, power, and political modernity. This investigation retraces a long, rigorous history without shortcuts, to understand what the Fulani destiny ultimately reveals about Sahelian Africa itself.

For decades, the Fulani were perceived as an anthropological given: a people of nomadic pastoralists, cattle herders roaming the Sahelian savannas in relative political indifference. Over the past fifteen years, they have become one of the most media-exposed groups on the African continent, often (and sometimes mechanically) associated with rural violence, land conflicts, and jihadist dynamics in the Sahel. This sudden centrality is no coincidence. It reveals a deep historical tension between an ancient way of life—based on mobility, social flexibility, and strong moral discipline—and a contemporary world structured by state borders, demographic pressure, resource scarcity, and the militarization of territories.

Understanding who the Fulani are therefore requires breaking away from the media snapshot and restoring a long history shaped by slow migrations, ambitious political constructions, religious transformations, colonial ruptures, and contemporary recompositions. The goal is neither to idealize nor to essentialize them, but to analyze what their trajectory tells us about Sahelian Africa as a whole.

Fulani: origins, empires, islam, and the sahelian crisis explained

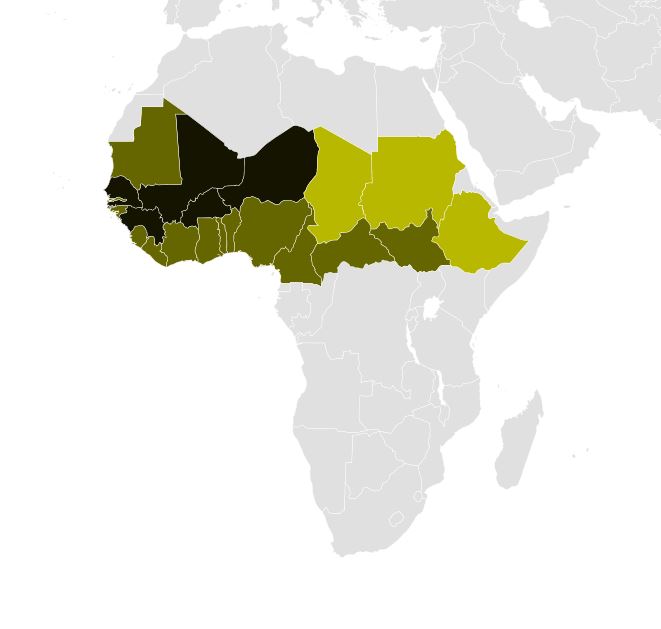

[Dark shading: Fulani constitute one of the main components of the country; medium shading: significant ethnic group; light shading: minority ethnic group]

The Fulani constitute one of the most geographically widespread human groups on the African continent. They are found from Senegal to Sudan, from Guinea to the borders of Cameroon and Chad, with particularly significant population centers in Guinea, Nigeria, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Cameroon. This dispersion is not anarchic fragmentation: it rests on ancient networks of pastoral circulation, kinship, marital alliances, and commercial exchanges.

Unlike peoples structured around a stabilized political territory, the Fulani have historically defined themselves through movement. They form less a nation than a human archipelago, connected by a common language (Fulfulde or Pulaar) and a relatively homogeneous set of social codes despite vast distances. This linguistic continuity is remarkable in an African space often fragmented by linguistic diversity. It facilitates mobility, local integration, and mutual recognition among dispersed groups.

Fulani identity thus developed more as a cultural and moral belonging than as a territorial inscription. It is transmitted through language, social practices, clan memory, and collective ethics. This flexibility explains both the group’s remarkable long-term resilience and its vulnerability to modern states, which privilege territorial fixation, cadastral logic, and administrative sovereignty.

Fulani oral traditions evoke prestigious ancestors, founding migrations, and semi-legendary figures meant to give meaning to group cohesion. These narratives serve a political and symbolic function: they inscribe the community in an honorable continuity and produce a sense of unity beyond geographic dispersion.

Modern historical and linguistic research shows, however, that Fulani identity does not stem from a single or homogeneous origin. It results from a slow process of cultural, linguistic, and biological intermixing among different Sahelian and Sudanic populations, in a context marked by ancient pastoralism, trans-Saharan exchanges, and contact with North Africa. Contemporary genetics confirms the existence of ancient admixtures, without allowing for the reconstruction of a linear or ethnically “pure” narrative.

This point is essential: the Fulani are not a fixed biological essence but a dynamic historical construction. Their identity was forged through progressive aggregation, the adoption of shared norms, and the transmission of a way of life and an ethic. This plasticity explains both their capacity for expansion and the persistent misunderstandings surrounding them: they are sometimes attributed a homogeneity they never possessed.

Pastoralism, social organization, and pulaaku

The historical core of Fulani society remains extensive livestock herding. Cattle are not merely an economic resource: they are a symbolic marker, a form of social capital, a tool for marital alliance, and an identity reference point. The herd constitutes a form of mobile savings adapted to unstable ecological environments, allowing mobility to be converted into relative security.

This pastoral economy imposes a specific social organization. Seasonal transhumance structures calendars, alliances, conflicts, and solidarities. It produces fine-grained knowledge of territories, climatic cycles, and ecological balances. But it also presupposes weak land fixation, which becomes a vulnerability in a context of agricultural pressure, urbanization, and rigid administrative demarcation.

Traditional Fulani society is hierarchical. It distinguishes noble lineages, specialized groups (blacksmiths, griots, artisans), and descendants of former captives. These hierarchies are not fixed but regulated by strict social rules, particularly marital ones. Honor, reputation, and conformity to collective norms play a central role in social regulation.

The central concept of Fulani culture is pulaaku. It is neither a political ideology nor a written code, but a set of moral dispositions valuing restraint, self-control, modesty, patience, sobriety, dignity, and endurance. Pulaaku values individual autonomy, the ability to endure hardship without complaint, and the refusal of excessive dependence.

This ethic produces relatively autonomous individuals capable of mobility and adaptation, but also sometimes perceived as distant or closed by sedentary societies. It fosters strong internal cohesion while limiting full integration into external political structures.

Historically, pulaaku enabled the Fulani to preserve a continuous identity despite dispersion and constant contact with other cultures. But it can also come into tension with modern state logics based on bureaucracy, taxation, and behavioral standardization.

Fulani states and islamic reform

From the seventeenth—and especially the eighteenth—century onward, a major transformation occurred: part of the Fulani elites engaged in a process of deepened Islamization, giving rise to reformist movements and theocratic states. These dynamics culminated in the formation of several major political entities: Fouta Toro, Fouta Djallon, the Macina Empire, the Sokoto Caliphate, and the Emirate of Adamawa.

These states were not improvised. They rested on disciplined military organization, structured religious administration, organized taxation, and an ambition to morally reform local societies. Jihad played a political as much as a religious role: it served to overthrow elites deemed corrupt, restructure social hierarchies, and impose a new legitimacy grounded in Islamic knowledge.

These experiences demonstrate that the Fulani were not merely nomadic pastoralists but also state actors capable of producing sophisticated political systems. However, these states remained fragile, dependent on a balance between religious authority, clan loyalties, and territorial control. Their limited centralization made them vulnerable to external shocks.

Fulani states were characterized by strong moral normativity: power was meant to be exercised in the service of religious justice, social discipline, and communal stability. Elites were subject to internal mechanisms of oversight. This political culture valued rectitude more than patrimonial accumulation.

Yet this organization made the transition to modern state forms particularly difficult. Bureaucratic administration, centralized taxation, and rigid territorial management were foreign to these structures, which relied on more flexible social equilibria. The encounter with European colonization would produce a brutal rupture.

Colonization, marginalization, and contemporary crisis

French and British colonial expansion gradually dismantled Fulani states. Theocratic structures were neutralized, religious authorities marginalized, and territories carved up according to administrative logics alien to local dynamics. Former elites became subordinate notables integrated into hierarchical colonial systems.

Pastoralism was particularly misunderstood by colonial administrations. Mobility was seen as an anomaly to be corrected, transhumance as an obstacle to taxation and control. Policies of sedentarization, census-taking, and taxation progressively disrupted traditional balances.

Colonization did not immediately destroy Fulani society, but it weakened its economic and political foundations, laying the groundwork for the structural difficulties of the twentieth century.

After independence, new states inherited arbitrary borders and centralized administrations poorly adapted to pastoral realities. The Fulani often became dispersed minorities across several countries, without genuine capacity for national collective representation.

Demographic growth, land pressure, agricultural expansion, and urbanization progressively reduced transhumance spaces. Former mechanisms of negotiation between herders and farmers eroded. Local conflicts took on political and security dimensions.

In some countries, Fulani elites reached the highest levels of state power, but this did not translate into structural improvement in pastoral conditions. State logics favored sedentary populations, fixed infrastructure, and intensive agricultural models.

Since the 2010s, Sahelian regions have experienced a rise in armed violence fueled by state fragility, transnational trafficking, local rivalries, and the implantation of jihadist groups. In this context, certain segments of marginalized Fulani populations—deprived of state protection and engaged in land conflicts—have found in armed groups a form of protection, revenge, or recognition.

This partial reality has gradually been transformed into collective stigmatization. The shortcut “Fulani = jihadist” has taken hold in some political, military, and media discourses. Community militias have formed, targeted massacres have multiplied, and the spiral of revenge has become self-sustaining.

This ethnicization of conflict is particularly dangerous. It destroys local solidarities, radicalizes positions, and traps entire populations in a logic of identity-based survival.

What the Fulani Trajectory Reveals About the Sahel

The contemporary fate of the Fulani reveals the Sahel’s structural contradictions: the growing incompatibility between pastoralism and territorialized states, ecological crisis, demographic explosion, security fragility, and deficits in local governance. The Fulani are not the cause of these crises, but they are a sharp indicator of them.

They embody a fundamental tension between historical mobility and administrative immobilization, between pastoral economy and land-based economy, between communal ethics and modern state sovereignty.

The Fulani are neither an eternally nomadic people frozen in tradition nor a homogeneous bloc responsible for contemporary disorder. They are the product of a long history of adaptation, ambitious political constructions, colonial ruptures, and modern fragilizations.

Their trajectory forces a rethinking of simplistic categories of ethnicity, nomadism, security, and development. It raises a central question: can the Sahelian space still integrate mobile societies within states founded on territorial fixation, administrative centralization, and economic standardization?

Through the Fulani, a decisive part of the Sahel’s future is at stake: either the capacity to invent hybrid political forms capable of articulating mobility, ecology, and citizenship—or long-term entrapment in a spiral of fragmentation and violence.

Notes and References

A. D. Roberts — The Colonial Moment in Africa: Essays on the Movement of Minds and Materials, 1900–1940, Cambridge University Press (1990).

E. Lovejoy & S. M. Falola (eds.) — The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Cambridge University Press (2003).

E. Sayad — The Double Absence: From the Illusions of Emigration to the Sufferings of Immigration, Seuil (1999).

Table of contents

Fulani: Origins, Empires, Islam, and the Sahelian Crisis Explained

Notes and References