A legendary city emerging from the edges of the desert and river, Timbuktu has successively been a caravan crossroads, an Islamic university, and the spiritual capital of the Sahel. From its Tuareg foundation to its post-jihadist revival, here is the story of an African center of knowledge and resistance—a forgotten symbol of rooted, scholarly Islam.

Timbuktu: the Sahelian exception between desert, faith, and knowledge

African history, too often told through the lens of silences or tragedies, nevertheless contains major centers of civilization that were ignored or distorted by a long-blind European historiography. Timbuktu, a frontier city between the Saharan sand seas and the fertile lands of the Inner Niger Delta, embodies one of the highest expressions of precolonial Sahelian civilization. Neither strictly a political capital nor a simple trade hub, for centuries it was a major spiritual, intellectual, and cultural center, nourished by the routes of gold, ink, and faith.

Yet Timbuktu was not born by imperial decree or royal whim. Like many African cities, it emerged at the intersection of several dynamics: Tuareg settlement, caravan trade, gradual and localized Islamization, absorption by the great Sudanese empires (Mali then Songhai), and finally its entry into Maghreb geopolitics with the arrival of Moroccan armies. Each stage of its development followed territorial, economic, or religious logic, in which Africa acted as a subject of its history, not a passive backdrop.

Timbuktu, therefore, is the story of a city without walls yet surrounded by legends—long feared by Europeans, idealized by Muslims, often forgotten by Africans. It is time to trace its history, beyond myths, as close to the facts as possible, through a rigorous reading rooted in Sahelian realities and in the spirit of a continent that, far from purely oral, also produced libraries, charters, thinkers, and empires.

Genesis of a Saharan outpost (11th–13th century)

Understanding Timbuktu first requires reading the terrain. Far from a creation ex nihilo or the result of imperial whim, the city is rooted in a geographical interface at the junction of three strategic zones: desert, savanna, and river. This ecological tripod, unique in West Africa, shaped human mobility, trade, and settlement for centuries.

At the heart of this dynamic lies the Inner Niger Delta, an amphibious region of oxbow lakes, marshes, alluvial plains, and dunes. This territory is not only fertile; it is foundational. It serves simultaneously as an agricultural basin, a pastoral reserve for Fulani and Moorish herders, and—most importantly—a fluvial corridor linking the Sahara’s edges to the Guinean savanna. In other words, whoever controls the delta controls the Sahel’s logistical key.

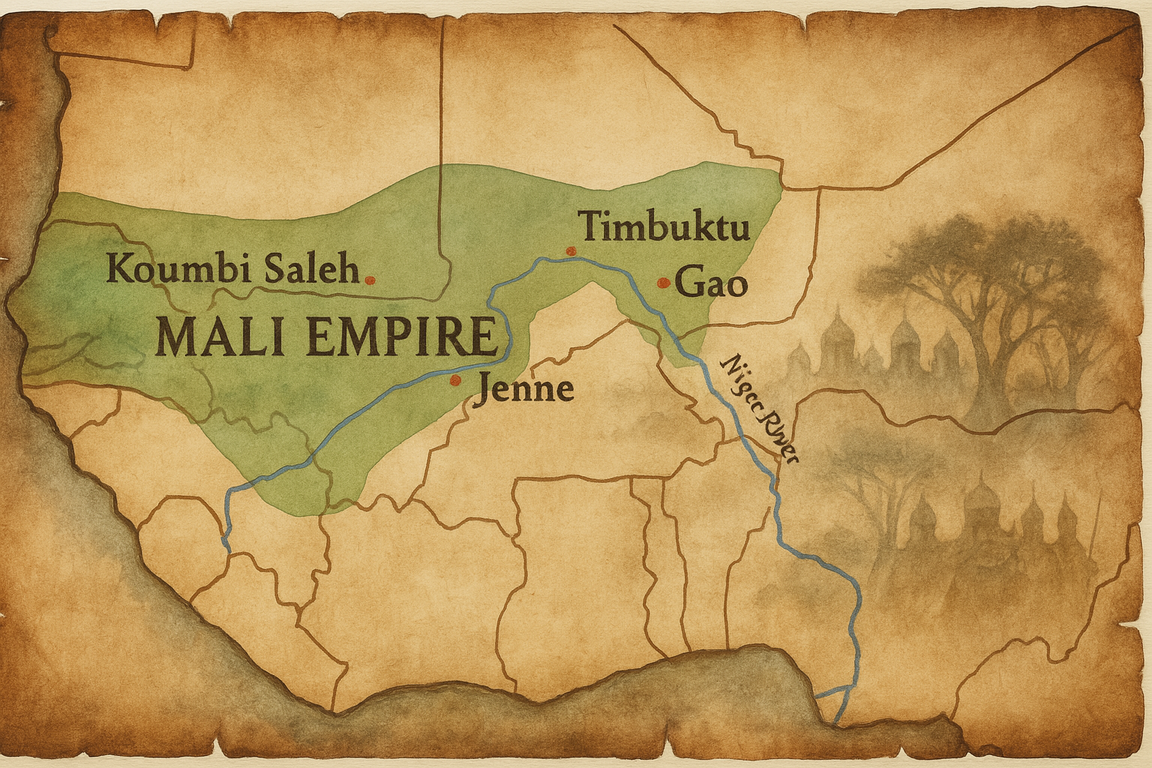

Further north, the advancing dunes mark the start of the Tuareg sand sea. Yet rather than a barrier, the desert acts as a highly structured circulation space, crisscrossed for centuries by major trans-Saharan caravans. Routes start from Sijilmassa, Ghadames, or Tindouf, pass through Taghaza (the salt mines), then split toward Gao or Timbuktu, before stretching south to Djenné or Koumbi Saleh. Timbuktu early on became a major stop on this commercial diagonal, at the intersection of Berber and Sudanese worlds.

This dual articulation—riverine and desert—makes the region a geo-economic hub. No other city on the Sahelian map combines so many advantages: hosting caravaneers, supplying fresh water for people and animals, storing salt and gold, negotiating with sedentary Soninke or Songhai communities. At a time when the state was still nascent and borders nonexistent, geography decided history: Timbuktu arose because it was necessary.

As in many prominent African sites, Timbuktu’s foundation cannot be rigidly dated, existing somewhere between history and collective memory. This ambiguity is not an obstacle to historical truth but a reflection of a world where writing was not the sole guarantor of legitimacy. The Tuaregs—more specifically the Imakcharen clan, a branch of the Kel Tamasheq—initiated this settlement in the second half of the 11th century.

These nomadic pastoralists, masters of the Saharo-Sahelian fringes, did not found cities but established encampments. At the river’s edge, at the junction of their transhumance zones and northern caravan routes, they set up precisely this type of post. Initially, Timbuktu was only a seasonal station, a resting area for humans and animals, with water points guarded by clan members.

The city’s very toponymy attests to this Tuareg rooting. “Tin-Bouctou,” literally in Tamasheq, means “Bouctou’s well.” Bouctou, according to oral tradition, was a wise and respected Tuareg woman entrusted with guarding the camp. This female figure, embodying domestic authority, knowledge transmission, and group security, reflects a Tuareg conception of power that is non-militaristic and matrilineal. This is not trivial: it reminds us that the city, before becoming an Islamic stronghold, was first a Sahelian matrix managed by women.

As trade flows increased, the Tuaregs settled part of their activity at this point. Without building a stone or mudbrick city (this would be the work of later Mande and Songhai sedentaries), they allowed the emergence of a structured outpost where Saharan caravans intersected with Black merchants from the south. They ensured the security of the routes, collected tolls, and arbitrated conflicts between clans and tribes. They were not builders but maintainers of balance.

Timbuktu’s destiny was shaped not by architecture or conquest but by the geography of trade flows. What was initially just a water point guarded by Tuaregs became, by the turn of the 12th century, a vital stop on trans-Saharan trade, favored by a specific geo-economic conjuncture: the growth of Sahelian trade networks and the gradual integration of West Africa into the global Islamic economy.

At the time, the great Sudanese empires (notably Ghana then Mali) organized and secured southern routes, while North African caravan cities (like Sijilmassa, Tindouf, or Ghadames) ensured logistical relay from the Maghreb. Timbuktu, ideally situated at the desert’s edge, at the southern exit of these routes, became a point of transfer and exchange between two worlds: nomadic and sedentary, Berber and Mande, salt and gold.

Tuareg caravans, sometimes hundreds of camels strong, stopped there to resupply, trade, and redistribute goods. Salt from the Taghaza mines, the Sahara’s “white gold,” was exchanged for gold from Bambouk, buried deep in Mande lands. Slaves captured in raids or delivered by southern chiefdoms were sold to be transported to oases or Atlas cities. Cereals from the Inner Delta (sorghum, millet, flood-recession rice) were a strategic resource to feed caravan travelers.

Soon, a regular market emerged, structured around Tuareg, Songhai, Fulani, and Mande traders, as well as Maghrebian Jews and Arabs from the north. It was not yet a city in the urbanistic sense, but a hub of interdependence, with brokers, granaries, and merchant camps. The settlement of trade preceded that of builders.

Trade was regulated: by the Tuaregs, through tolls and fees, and also by the merchants themselves, under unwritten but strongly respected rules, derived from sanankuya (joking cousinship) and interethnic hospitality pacts.

Integration into the great west african empires (13th–16th century)

Commercial power calls forth political power. As Timbuktu established itself as a hub of Sahel-Saharan trade, it attracted the attention of those to the south seeking to secure and capture these flows to feed their imperial centrality. These were the emperors of Mali, whose territorial expansion at the turn of the 14th century incorporated Timbuktu into a logic that was both strategic and symbolic, imperial and Islamic.

The annexation of the city occurred without a spectacular battle or a formal siege. Unlike other cities taken by force, Timbuktu entered the Malian orbit through a dual process: diplomatic and commercial. Historiography agrees in situating this integration during the reign of Mansa Musa (1312–1337), a charismatic and visionary figure, who gave the Mali Empire a pronounced Islamic dimension on the Afro-Maghrebian and Middle Eastern stage.

The logic is clear: for a Muslim sovereign seeking international recognition, control of commercially and symbolically valuable crossroads is essential. By annexing Timbuktu, Mansa Musa not only captured a caravan stop: he also gained a diplomatic lever with the ulama of the Islamic world, as well as a foothold in trans-Saharan trade circuits. The city became a northern imperial outpost, complementary to Gao on the river and Djenné further south.

This change in status was accompanied by a first urban transformation. From the 14th century, the first banco constructions were erected, breaking with the nomadic aesthetics of its origins. These were not yet the great mosques of the golden age, but rather discreet foundations: places of prayer, residences for merchants and scholars, warehouses, and weighing centers. Architectural influence came from the Mandé heartland, but also from builders from the Maghreb, drawn to the Malian court. The most famous case being Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, an Andalusian poet who became a court architect after Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca.

But beyond stone, it was learned Islam that took root. For Mali, while remaining an African empire founded on clan and lineage structures, now saw itself as a legitimate Muslim power, protector of the faith. Timbuktu thus became a relay for Malian religious authority, a place of passage for jurists, imams, and students coming from the heart of the empire or the Maghreb.

This process did not erase preexisting social complexity: the Tuaregs retained local influence, merchants remained autonomous, and African traditions persisted. But a new power insinuated itself: imperial power, distant but structuring, introducing taxation, armed security, and legitimacy through Islamic law.

In precolonial African history, the spread of Islam did not follow a logic of military conquest but an elite-driven dynamic, where pilgrimage, diplomacy, and economy charted the paths of faith. In this regard, Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 constituted a decisive turning point: not only for the image of the Mali Empire on the global Islamic stage, but also for the religious structuring of its cities, foremost among them Timbuktu.

Tradition reports (and Arab chronicles confirm) that the Malian sovereign traveled at the head of several thousand men and tens of tons of gold, distributing lavish gifts to the elites of Cairo and Mecca, even causing monetary inflation in some regions of the Near East. But beyond the spectacular, this pilgrimage had a political purpose: to inscribe Mali into the umma, the community of believers, and thus religiously legitimize his imperial power. It was not an isolated act of faith, but a calculated diplomatic gesture.

Upon his return, Mansa Musa was not alone: he was accompanied by scholars, architects, scribes, and jurisconsults, among whom the most famous was Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, an Andalusian literatus, poet by training, turned builder by pragmatism. The latter, installed at the imperial court, is said to have initiated the adoption of certain Maghrebian architectural norms in the Niger Valley, notably in Gao, Djenné, and Timbuktu. Even if al-Sahili’s role may have been idealized by Arab chroniclers, his presence symbolizes Mali’s intellectual openness to learned Islam.

Timbuktu benefited directly from this openness. For what the pilgrimage triggered at the top of the state, the desert city translated into its walls: installation of jurists trained in Fez or Kairouan, development of mosque-schools (the oldest being Djingareyber), constitution of a body of learned clerics teaching Maliki law, Ash’ari theology, Arabic grammar, and rhetoric.

These schools, relying on private foundations and merchant patrons, were not part of a centralized state educational system, but a decentralized and organic network, as in the rest of the Islamic world. This is what allowed their resilience: each scholar attracted his students, each mosque became an intellectual center, each learned family established its prestige through the transmission of knowledge.

Far from being a rupture, this learned Islam fits within a distinctly African continuity: earlier practices of griot storytelling, oral memory, and public commentary on sacred texts found an Islamized translation, without abrupt disappearance. The Islam of Timbuktu, although orthodox in its legal form, remained African in its social and pedagogical dynamics.

By the mid-15th century, the Malian imperial horizon collapsed due to internal crises, dynastic quarrels, and weakening provincial networks. It was into this vacuum that the Songhai Empire, founded from Gao, rose, whose rapid westward expansion heralded a political reconfiguration of the central Sahel. In this context, Timbuktu became a major strategic prize: not only for its commercial wealth, but above all for its religious and intellectual influence, now a tool of imperial legitimacy.

The city was first taken militarily by Sonni Ali in 1468, following a brutal campaign aimed at breaking the autonomous power of the ulama and bringing the city under Songhai control. According to chroniclers, the animist, pragmatic, and authoritarian sovereign repressed religious notables resisting his dominance, causing a first rupture in the scholarly management of the city. Under Sonni Ali, Timbuktu was conquered but not yet invested with its intellectual dimension: it was captured, not yet integrated.

It took his successor, Askia Muhammad (1493–1528), for a second, foundational phase to begin, this time peaceful and structuring. A devout Muslim, pilgrim to Mecca, and religious reformer, Askia transformed military conquest into ideological integration. Under his reign, Timbuktu became the heart of Sudanese Islam, a model of a theocratic empire organized around Maliki sharîʿa law.

The reform proceeded through a dual policy: institutional construction and centralization of the ulama. It was at this time that the three great emblematic mosques of the city reached their full importance:

- Sankoré, more than a place of worship, became a true Islamic university, housing up to 25,000 students and a library of manuscripts of exceptional richness. It was supported by merchant patrons and integrated into the scholarly networks of the Muslim world.

- Djingareyber, renovated and expanded, became a royal mosque, symbolizing the emperor’s authority over the faith.

- Sidi Yahya, finally, embodied local spiritual diversity, housing prayer, teaching, and mediation.

Simultaneously, the Songhai state implemented a policy of legal codification, entrusting the ulama with managing civil affairs, commercial disputes, inheritances, and marriages. It was a form of centralization through knowledge: the power did not impose the law, it delegated its authority to Maliki law, which became a tool of homogenization in a multiethnic empire. The ulama here played a role equivalent to European royal administrators, but in the language of fiqh.

Far from mere outward piety, Askia Muhammad’s policy demonstrates a desire to root the Songhai Empire in a global Islamic legitimacy. Relations were established with Cairo, Tlemcen, Fez, and Mecca. Scholars came to teach, manuscripts circulated, diplomas were exchanged. Timbuktu became the black Fez of the Sahel, a literate city, sanctuary of orthodoxy, scholarly showcase of an African empire fully integrated into the Muslim community.

Intellectual peak and Islamic influence (15th–16th century)

If Timbuktu established itself as the Sahelian capital of trade, it above all inscribed itself in history as the capital of African Islamic intelligence. From the 15th to the 16th century, the city experienced an unprecedented scholarly effervescence in sub-Saharan Africa. It was not only a city of prayer but a metropolis of religious, legal, and scientific education, rivaling Fez, Cairo, or Kairouan at the time. In this period, knowledge was no longer transmitted solely in the shade of tents, but in libraries, law courses, and treatises on astronomy.

The foundation of this efflorescence rested on a unique institutional triangle: Sankoré, Djingareyber, Sidi Yahya. These three mosques, simultaneously places of worship, centers of teaching, and libraries, embodied the convergence of spirituality, pedagogy, and scholarly power.

Sankoré, first. Founded as early as the 14th century but developed at its zenith under Askia Muhammad, this mosque-university became the beacon of Maliki knowledge south of the Sahara. Funded by wealthy merchants, equipped with hundreds of manuscripts imported or written locally, it attracted students from across the Sudanese world. Subjects taught included Arabic grammar, logic, Islamic law (fiqh), rhetoric, mathematics, and astronomy. Certain masters, such as Ahmed Baba, enjoyed such prestige that they were invited to courts in Morocco or Cairo.

Djingareyber, rebuilt in banco by Abu Ishaq al-Sahili in the 14th century, became the royal mosque par excellence, where public prayer, Friday sermons, and major lessons converged. It embodied the link between Islam and imperial power, between faith and political authority. It was there that the ulama justified the legitimacy of the askia, arbitrated jurisprudential debates, and issued fatwas.

Sidi Yahya, later (late 15th century), represented the spiritual diversity and internal tolerance of Timbuktu’s Islam. Less directly connected to imperial power, it was a center of popular devotion and mystical transmission, where teaching touched on Sufi spirituality as much as on fiqh.

This triangle did not rely on a centralized Western-style university model. It was a flexible network of masters and students, often organized by scholarly lineages, study circles, or zawiya. The city lived to the rhythm of theological debates, Quranic recitations, and public readings. Discussions ranged from Mu’tazilism to commentaries on Al-Ghazali, interpretations of Ibn Rushd. Knowledge circulated, manuscript by manuscript, memory supporting transmission.

But this intellectual effervescence was not autarkic. Thanks to merchant networks and pilgrimages, Timbuktu was connected to the great cities of the Muslim world: manuscripts came from the Hijaz, Cairo, and al-Andalus; diplomas were exchanged with Fez; correspondence was maintained with scholars in Tlemcen and Tunis. Timbuktu stood at the center of an Islamic Republic of Letters on a Sahelo-Mediterranean scale.

It must be emphasized: this centrality was neither myth nor postcolonial nostalgia. It is documented, archived, preserved in the thousands of manuscripts still held in the city’s family libraries, despite plundering and fires.

If Timbuktu shone through its institutions, it would never have radiated without the men who carried its thought. Africa, like any other civilization, is not told only through its empires or trade exchanges, but through its intellectual lineages, its masters, its commentators, its thinkers. In Timbuktu, the elite was not of the sword but of the pen. The literati were the true architects of its renown, transmitters of Islamic knowledge, guardians of orthodoxy, and social mediators.

Among these figures, Ahmed Baba of Timbuktu (1556–1627) occupies a central place. A Maliki jurist, theologian, grammarian, and biographer, he embodied the pinnacle of Sahelian scholarly culture, at the crossroads of Black Africa and the Arab-Islamic world. Born into one of the city’s great learned families, he received a complete education at Sankoré, composed legal and historical works early on, and became a reference for Sudanese fiqh. His literary production includes more than 40 works, including treatises on jurisprudence and biographical catalogs of African scholars.

But his destiny shifted with the Moroccan conquest of 1591. Refusing to submit to the sharifian invaders, Ahmed Baba was arrested and exiled to Marrakesh with several notables. There, instead of being marginalized, he was recognized for his scholarship and even gained the esteem of Maghrebi ulama. His exile, far from annihilating him, made him a living symbol of literate, dignified, and resistant African Islam. He embodied, in the eyes of the Muslim world, the intellectual fertility of the Bilād as-Sūdān.

But Timbuktu was not reducible to a single figure. It thrived through its learned families, true dynasties of knowledge. The most illustrious were the Kati and the Aqit. The Kati, allegedly descended from a converted Andalusian, were behind many legal and historical works, including the famous Chronicle of Timbuktu. The Aqit, for their part, formed a lineage of judges (qadis) across generations, ensuring the continuity of Islamic law in an African context, providing the city with legal stability based on Maliki jurisprudence.

Around these lineages revolved scribes, copyists, and anonymous masters, artisans of the book and memory. In Timbuktu, the manuscript was a sacred object, carefully copied, sometimes adorned with calligraphy or marginal glosses. Each work was a living object, annotated, transmitted, gifted, or sold through family or merchant networks. The book became currency, heritage, a prestige tool, and an act of faith.

In this way, Timbuktu’s literati built a true knowledge society, rooted in African traditions while fully integrated into Islamic norms. Their role went beyond teaching: they acted as intermediaries between power and the population, diplomats between cities and caravans, guardians of a lucid, rigorous, and rooted Sahelian Islam.

In the Sahelian zone, where sand erodes walls and memory is transmitted orally, Timbuktu was exceptional: the city made writing its shield, ink its gold, manuscript its civilizational banner. From the 15th to the 17th century, it was not only a center of education but a continent-scale scriptorium, a crossroads of the book where thousands of texts were exchanged, copied, and commented upon.

Far from clichés associating Africa with generalized orality, Timbuktu proves the existence of a distinctly African literate culture, rooted in Islamic law but extending to all fields of classical Islamic knowledge: exegesis, grammar, medicine, astronomy, logic, Sufism, poetry, agriculture, and even diplomacy. This profusion rested on a triple dynamic: importation, local copying, and private preservation.

First, importation. From the 14th century, with the first pilgrimages of Malian and Songhai rulers, ties strengthened between the Bilād as-Sūdān and the intellectual centers of the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the Mashreq. Merchants brought religious treatises from Tlemcen, grammars from Fez, medical works from Cairo, and even philosophical texts from al-Andalus. These books became objects of prestige, as well as pedagogical matrices for local schools, foundations of teaching, and sources for reproduction.

Then, local copying. Timbuktu’s scholars did not merely read: they copied, translated, and commented. A true manual and scholarly industry emerged, with professional scribes, calligraphers, and binders. Paper was imported, ink manufactured locally, often from gum and soot, and quills carefully cut. Each copied work became unique, marked by regional styles and enriched with marginal glosses expressing local thought. These ranged from simple legal collections to vast hagiographic compilations or precise genealogical lists.

Finally, preservation. Here lay perhaps Timbuktu’s greatest originality: manuscripts were preserved not in a centralized public library but within families. Each scholarly lineage held its works, hiding or displaying them according to political risks. These domestic libraries, sometimes secret, sometimes open to selected students, ensured the transmission of knowledge over centuries. Even today, hundreds of families in Timbuktu, Djenné, or Gao possess such treasures, protected against plundering, fire, or foreign conquest.

The scope of this heritage is staggering: estimates speak of more than 700,000 manuscripts scattered across the region, often intact despite the trials of time. They include treatises on Islamic law, commentaries on Ibn Ajurrum’s grammar, correspondence between scholars, astronomical records, and even previously unknown local works. It is a continent of paper, buried in the desert, the memory of a literate, scholarly, and sovereign Africa.

Decline, conquests, and marginalization (1591–19th century)

By the end of the 16th century, Timbuktu was no longer just a city: it had become a symbol. Symbol of African learned Islam, of trans-Saharan commercial prosperity, of Songhai political power rooted in Sahelian tradition. It was precisely this prestige, as much as the region’s gold resources, that drew the attention of an ambitious Moroccan sultan: Ahmad al-Mansur, of the Saadian dynasty.

The geopolitical context was decisive. Morocco, freshly victorious against the Portuguese at the Battle of the Three Kings (1578), sought to assert its legitimacy as a shining Muslim power. But the Saadian throne was fragile, contested, threatened by internal tensions. Ahmad al-Mansur, attempting to redirect instability outward, planned a military expedition to the heart of western Sudan. Public objective: control the gold mines of Bouré and Bambouk. Implicit objective: demonstrate force and subjugate a black Islam deemed autonomous, even too independent.

The expedition was carefully prepared. In 1590, an expeditionary force of about 4,000 Moroccan soldiers, led by Turkish officers and armed with arquebuses, crossed the desert at forced march. Although numerically limited, this army had a decisive technological advantage over the Songhai: gunpowder. At its head was the feared pasha Judar, a Spanish renegade turned Muslim, an energetic but brutal general.

In 1591, the Moroccan army reached Gao and destroyed the Songhai army at the Battle of Tondibi. The shock was severe: Songhai cavalry, despite their bravery, could not withstand the firepower of the arquebusiers. Timbuktu, without real military defense, fell soon after without a fight. But the true drama unfolded after the conquest: the city, intellectual pride of West Africa, became an occupied territory, subject to foreign military power, Muslim indeed, but foreign in its forms, logics, and methods.

The ulama, guardians of law and memory, were particularly targeted. The Saadian power, wary of their prestige and influence, ordered the arrest, deportation, and even execution of many scholars. The most emblematic case was Ahmed Baba of Timbuktu, the leading intellectual of his time, arrested, humiliated, and deported to Marrakesh. There, despite the admiration he inspired, he refused to collaborate with power and became a symbol of resistant and dignified black Islam facing northern interference.

This invasion marked the end of Timbuktu’s political autonomy. The Moroccans installed a military governorship (local pasha), recruited local troops to control the region (the Arma, Hispano-Maghrebian mestizos), and imposed heavy and arbitrary taxes. Yet their control remained superficial, constantly contested by Fulani chiefdoms, Tuareg militias, and Songhai populations. The occupation never transformed into integration.

Even worse: trans-Saharan trade, pillar of local prosperity, was durably disrupted. Caravans diverted, routes shifted, North African markets turned toward the Atlantic. By the late 17th century, Timbuktu entered a long phase of political and economic marginalization, reduced to a symbolic and scholarly role, peripheral to major flows of the Muslim world.

The Moroccan occupation after 1591 gave rise neither to structured colonization nor stable administration. It was a military occupation without political project, a mere foreign garrison perched on a fundamentally hostile Sahelian base. Far from bringing order, it generated a chronic instability, fueled by both the weakness of the sharifian command and the resilience of indigenous powers.

Effective authority was entrusted to a governor called a pasha, installed in Timbuktu as representative of the Saadian sultan. But this envoy, often disavowed or abandoned by Marrakesh, depended on his own troops (the Arma) to maintain a semblance of authority. These Arma, descendants of former Moroccan soldiers established locally and mixed with the local population, formed a hybrid military caste, without popular base, torn between loyalty to the Maghreb and African roots.

Very quickly, the pasha’s authority eroded. Commercial circuits were disrupted. Trans-Saharan trade, in decline, no longer financed the ambitions of governors. Caravans bypassed Timbuktu in favor of safer routes. The absence of resources, metropolitan support, and religious legitimacy led to revolts, mutinies, and coups. Pashas succeeded one another amid intrigue; their authority sometimes did not extend beyond the city walls.

In this political vacuum, the Kel Essouk and Imghad Tuaregs, long kept distant from centers of power, returned to play a role. Desert people, masters of caravan routes and formidable horsemen, they sporadically regained control of Timbuktu’s peripheries, and at times the city itself. This was especially the case in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the Tuaregs acted as protectors, extortionists, and sometimes city lords, imposing authority over markets, routes, and mosques.

This Tuareg domination was not unified: the Kel Essouk in the north, the Imghad closer to the lowlands, acted as independent chiefs, basing their authority on control of routes, collection of zakat, and the constant threat of the sword. They did not aim to administer the city according to imperial schemes, but to profit from it while maintaining the autonomy of nomadic confederations.

The result of this double domination—Moroccan in façade, Tuareg in fact—was a century and a half of political drift, where Timbuktu survived, but on the margins, without stable leadership, political program, or central religious project. Its scholarly elite maintained, as best they could, the memory of a glorious past, but without central power to relay it. The ulama became notables without power, the manuscript archives lay dormant, the mosques citadels of silence.

Timbuktu’s marginalization was not the result of a single conquest or disaster. It was more insidious: a slow suffocation through peripheralization, a progressive geopolitical erosion caused by the recomposition of regional and global economic axes. In other words, Timbuktu was not destroyed; it was surpassed.

At the turn of the 18th century, the great trans-Saharan trade, pillar of its prosperity for five centuries, gradually collapsed. Three major factors contributed to this decline:

- Chronic insecurity of caravan routes, now subject to Tuareg raids, arbitrary levies by the Arma, or blockades imposed by rival chiefdoms.

- Structural decline of major northern Saharan markets, especially Sijilmassa and Tindouf, themselves weakened by internal Moroccan turmoil and Atlantic commercial competition.

- Rise of the Atlantic coast, notably around Saint-Louis, Gorée, or Porto-Novo, which now captured most trade in gold, slaves, and textiles, bypassing desert routes.

Hence, Timbuktu found itself isolated at the heart of the continent, far from the new lines of force of nascent merchant capitalism. Europe entered Africa by the sea, not through the Sahara. The salt of Taghaza was no longer strategic, gold was extracted elsewhere, caravans became scarce, and major merchant families dispersed.

This shift was accentuated in the 19th century by French colonial expansion. First in Senegal, then toward the Upper Niger, the colonial administration introduced new exchange circuits, new economic capitals (Saint-Louis, then Bamako), and new taxation and production methods. Timbuktu became an administrative cul-de-sac, a symbolic outpost, without real influence over commercial flows.

The local economy then retreated to subsistence activities, punctuated by local fairs but without international outlets. The scholarly elite, without state patronage or merchandise flows, fossilized, maintaining a veneer of erudition but without political or social projection. Manuscripts gathered dust, mosques cracked, ulama became notaries rather than jurists.

The French conquest of 1893 by Colonel Bonnier provoked no notable resistance. Timbuktu was no longer a strategic stake but a famous toponym, annexed for prestige and to assert domination over French Sudan.

French colonization and rediscovery (late 19th–early 20th century)

Timbuktu under Colonial Rule and Contemporary Challenges

Timbuktu’s entry into the colonial orbit was neither heroic nor negotiated. It was the mechanical result of French expansion from Senegal toward the Upper Niger, following a strategy of encirclement and a “military oil-spot” logic, under the guise of a civilizing mission. For officers of the Third Republic, taking Timbuktu had only symbolic value—but all the more essential, as its legendary name resonated in Parisian salons as that of a “mysterious desert city,” inaccessible and mythic.

The operation was carried out in 1893 by Colonel Eugène Bonnier, leading a column of Senegalese riflemen and local auxiliaries from Mopti. The enterprise was as much a demonstration of force as an act of imperial cartography: planting the French flag on a city celebrated in the media but geopolitically marginal. Poorly prepared, the column was intercepted and decimated by Tuareg armed groups at Takoubao, a humiliating episode that forced the high command to dispatch reinforcements.

It was ultimately Commander Joffre (the future Marshal) who restored order. In January 1894, French troops entered Timbuktu without significant resistance from the population, yet determined to suppress any regional dissent. The Kel Antessar Tuaregs, the Imghad, and other confederations launched sporadic offensives in the following months, but their desert-harassment tactics, while effective in the open terrain, collided with the French columns’ firepower and logistics, now well-equipped and coordinated.

Occupation soon took on a systematic character: military posts, secured caravan routes, traffic control, and taxation. Timbuktu became a garrison of the colonial empire, administered not by civilians but by a military administration under the “French Sudan,” one of the major entities of French West Africa (AOF). The goal was twofold: silence Tuareg resistance and integrate the region into an administrative grid, exploiting both its human and symbolic resources.

Yet the French quickly encountered a bewildering reality: Timbuktu, mythologized by European travelers, no longer possessed the economic or religious centrality they imagined. Manuscripts were abundant, but the city lived in the memory of its past grandeur. Mosques were empty or dilapidated, ulema discreet, and merchants scarce. The conquest was, above all, a reappropriation of myth—a prestige act for the Republic rather than a genuine strategic gain.

However, in their quest for legitimacy, colonial authorities began a process of “rediscovery” of Timbuktu’s past. French scholars started cataloging manuscripts, questioning learned families, and mapping the old quarters. Erudite Africa, previously ignored or denied, began to interest imperial anthropology—not without condescension, but with a methodical curiosity.

Even before its conquest, Timbuktu had been imagined. In many ways, its place in the European imagination preceded—and even provoked—colonization. The “forbidden city,” the “Black Eldorado,” the “African Athens”: such expressions, dating from the 18th century, fueled orientalist fantasies, colonial projections, and exploratory missions, soon used as a pretext for military intrusion.

The Enlightenment-era Europe, seeking geographic knowledge and new markets, discovered through Arab chronicles and Maghrebi traders’ accounts the existence of a mysterious city at the edge of the Sahara, renowned for its wealth, manuscripts, and mosques. Timbuktu thus became a Grail of exotic geography, poised between the reality of Muslim Africa and the golden fiction of tropical opulence.

It is in this context that René Caillié, the first European Christian to reach the city and return alive, emerges. Disguised as a Muslim pilgrim, he entered Timbuktu in 1828, alone, ill, yet determined to demystify the myth. What he discovered—or believed he discovered—disappointed him: a dusty, impoverished city, marked by decline. His account, published in Paris as Voyage à Tombouctou et à Jenné, sharply contrasted with fantasies of wealth. Yet the myth persisted. Europeans were less interested in what Caillié saw than in the past prestige his narrative allowed them to imagine—a past to be revived under colonial oversight.

A quarter-century later, German explorer Heinrich Barth, sent by the British, visited Timbuktu in 1853. Unlike Caillié, he mastered Arabic, engaged extensively with local scholars, and recognized the city’s cultural depth despite its political weakening. His Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa remains an erudite, precise, and respectful work. He described a learned society structured around jurist families and attested to the existence of authentically African manuscript knowledge, written in Arabic by Black Muslim authors. Yet these observations were largely ignored by the emerging colonial administration, which preferred the fiction of an empty desert to the history of an intellectual Africa.

In the French orientalist tradition, Timbuktu became a mirror city. Europeans projected either the vanished grandeur of African civilizations or the decadence of Muslim societies onto it. For soldiers, it was a remote post to secure; for writers, a sand-and-silence backdrop for post-romantic reveries. Myth supplanted reality.

At the heart of this dual gaze—wonder and condescension—remained a constant: the inability to recognize Timbuktu as an autonomous African intellectual center, forged by its own dynamics and not merely by echoes from the wider Islamic world. This political reading, more than historical, explains many misunderstandings of the colonial period, when the past was inventoried without being truly understood.

Timbuktu’s passage under French domination marked a radical rupture in the management, transmission, and meaning of its heritage. What had been living knowledge—transmitted by ulema, interpreted by learned families, consulted in legal or spiritual debates—became, under colonial administration, an object of study and display. In short, the transition moved from scholarly library to ethnographic exhibit.

By the early 20th century, colonial administrators were struck by the abundance of manuscripts preserved in Timbuktu’s family libraries: texts on Maliki law, Arabic grammar, traditional medicine, astronomy, as well as private letters, contracts, and historical chronicles. Their conservation had occurred without state intervention or formal institutions: scholarly memory was maintained by ulema lineages such as the Aqit and Kati, custodians of knowledge for centuries.

French authorities, influenced by Maghrebi orientalist methods, then began a process of collection, classification, and preservation, partially directed by European scholars. These initiatives, erudite in ambition, detached manuscripts from their living context, archiving, mapping, and sometimes transferring them to Dakar or Paris.

Similarly, the city’s architectural heritage—mud-built mosques, scholars’ homes, revered tombs—was incorporated into a museological logic. The colonial administration, seeking civilizing justification, began inventorying sites and “protecting” them according to European heritage norms. Djingareyber Mosque, for example, became emblematic not for its cultic function, but as a “historic monument” of a past grandeur to be framed.

This museification was part of a larger logic: a colonial narrative of heritage, where the vestiges of the past illustrated present decay and justified French tutelage. Timbuktu thus became an open-air museum of a bygone African golden age, with the Republic positioning itself as enlightened guardian. A subtle but meaningful inversion: the colonizer presented itself as the savior of what it had first marginalized.

It should be noted that this “preservation” was often partial. Mud architecture was not restored according to local knowledge, manuscripts were classified without contextualization, and learned families were excluded from conservation decisions. Heritage became administrative dossier rather than living corpus.

Ultimately, while colonial authorities may deserve credit for preventing the physical loss of some treasures, one must also recognize the symbolic dispossession they imposed. Manuscripts were no longer tools of autonomous African knowledge but objects of Western knowledge about Africa.

It is within this tension—between preservation and confiscation, curiosity and control—that Timbuktu’s heritage destiny played out in the 20th century: a city whose stones spoke, yet were silenced to be placed under glass.

Contemporary Challenges and Sahelian Memory

At the heart of Mali’s 2012 crisis, Timbuktu fell to Ansar Dine and AQIM, two jihadist groups linked to al-Qaeda. Their forces occupied the city from June 2012, instituting a radical theocracy and proscribing anything contrary to their puritanical vision of Islam.

The destruction was symbolic. Between June 30 and July 2, 2012, jihadists demolished nine Sufi saint mausoleums (some UNESCO World Heritage sites) and the sacred gate of Sidi Yahya Mosque with pickaxes and iron bars, affirming their rejection of all forms of worship deemed idolatrous.

The international community reacted forcefully. The Malian government immediately listed the city as a World Heritage site in danger. UNESCO and the UN Security Council condemned the destruction as war crimes, the first such cases judged by the International Criminal Court (ICC). In 2016, Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, one of the perpetrators, was sentenced to nine years in prison by the ICC.

Faced with urgency and danger, the people of Timbuktu responded with quiet determination. Learned families, notably the Haïdara family, organized clandestine evacuations of hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, hidden in underground caches or moved to Bamako. Sources estimate that around 300,000 to 350,000 documents were saved, often at extreme personal risk.

In parallel, international organizations launched digital preservation programs: the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project, supported by the University of Cape Town, and the Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation cataloged and digitized thousands of manuscripts, mainly from private libraries such as the Haïdara family collection. These initiatives complemented efforts at physical restoration, notably at the Mamma-Haïdara Memorial Library, which houses around 42,000 manuscripts and serves as a regional model.

Reclaiming the heritage site was not only a material restoration but also symbolic and civic. In 2015–2016, with UNESCO and MINUSMA support, 14 destroyed mausoleums were rebuilt by local artisans using traditional techniques and reconsecrated in a collective ceremony in February 2016.

This was more than an archaeological project: it was cultural resistance—reasserting Timbuktu as a living symbol of tolerant, literate African Islam rooted in knowledge, against those who sought to enclose it within a uniform dogma. The city once again shines as an intellectual beacon in the Malian and African imagination, reinforcing its memorial sovereignty and cultural diplomacy.

Timbuktu today is far more than a static relic: it is a city rebuilt by its inhabitants, whose renewed intellectual and heritage activity testifies to the vitality of a recovered Sahelian memory.

Timbuktu: Africa’s memory and a civilizational stake

Timbuktu is not just another Sahelian city. It embodies, in itself, the continuity of a learned, Muslim, literate, and sovereign Africa. From the sands of the Niger’s inner delta to the subterranean libraries of the medina, it demonstrates that West African societies built, without European assistance, religious, intellectual, and commercial institutions of remarkable complexity.

Its historical trajectory—from its Tuareg foundation in the 11th century to the post-jihadist reconstructions—reveals a capacity for adaptation and resilience that contradicts all condescending or miserabilist readings of Africa’s past. Timbuktu was successively a trans-Saharan crossroads, the spiritual center of the Mali Empire, an Islamic university under the Songhai, an object of colonial fantasies, and finally a symbol of reclaimed African memory.

A city at times coveted, forgotten, destroyed, and restored, Timbuktu is also a battleground of memory: between those who seek to erase African history and those who aim to use it as a lever of sovereignty. This is the core of its contemporary challenge: to make its heritage not a folkloric backdrop for tourists or foreign scholars, but a soft power tool for civilizational reaffirmation in a Sahel increasingly confronted by the war of narratives.

Today, Timbuktu’s revival depends less on NGOs or UNESCO than on Africans’ ability to defend their own past, control the means of its transmission, and transform it into a source of intellectual and political strength. The city of 333 saints has not spoken its last word: it remains, always, the historical conscience of West Africa.

Sources

- Walker, Robin. The Manuscripts and Intellectual Legacy of Timbuktu. Gresham College Lecture Series.

- Timbuktu: An Islamic Cultural Center. Library of Congress.

- “Timbuktu Scholarship: But What Did They Read?” Journal of the History of Ideas (University of Chicago Press).

- “Timbuktu: A Refuge of Scholarly and Righteous Folk,” JSTOR.

- Oxford Research Encyclopedias – Ahmed Bâba al-Timbukti.

- Al‑Saʿdī, Abderrahman. Tarīkh al‑Sūdān.

- Wikipedia – Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library.

- Wikipedia – Timbuktu Manuscripts.

- National Geographic Education – A Guide to Timbuktu.

Table of Contents

- Timbuktu: The Sahelian Exception Between Desert, Faith, and Knowledge

- Genesis of a Saharan Trading Post (11th–13th century)

- Integration into the Great West African Empires (13th–16th century)

- Intellectual Apex and Islamic Influence (15th–16th century)

- Decline, Conquests, and Marginalization (1591–19th century)

- French Colonization and Rediscovery (late 19th–early 20th century)

- Contemporary Challenges and Sahelian Memory

- Timbuktu: Africa’s Memory and a Civilizational Stake