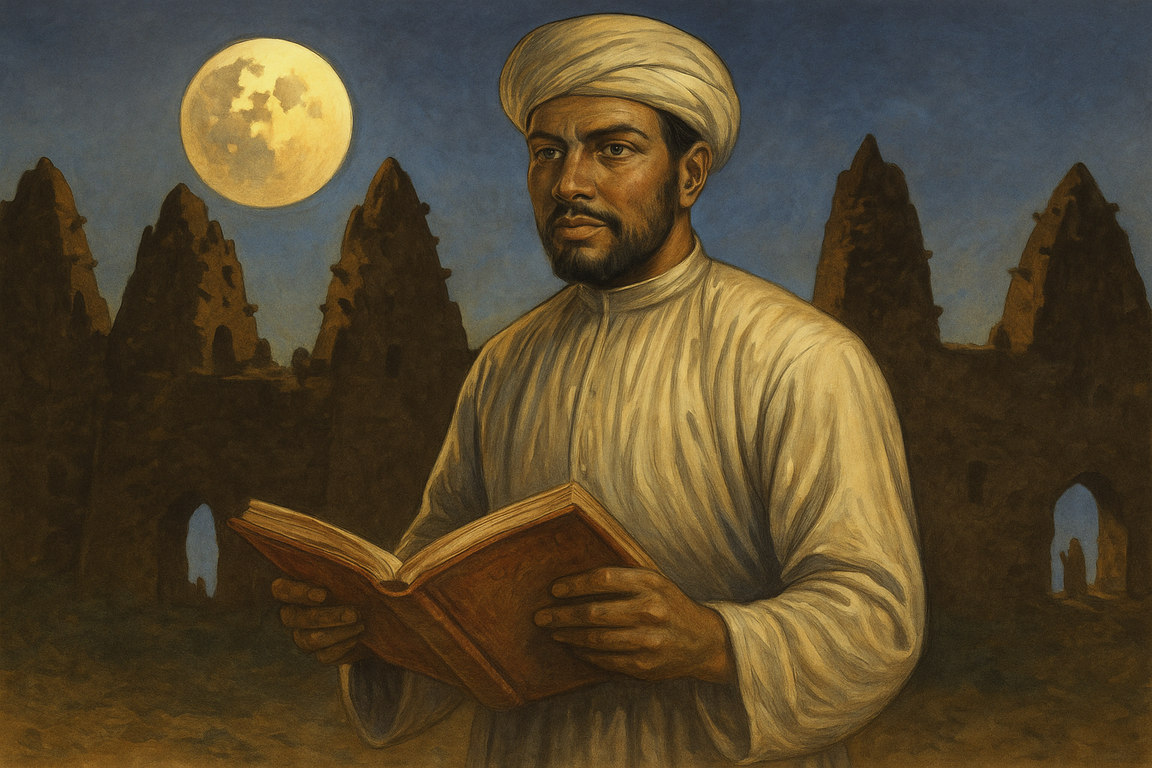

An emblematic figure of the sahelian intellectual golden age, Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī was at once a maliki jurist, a political exile, and a defender of a learned black islam against foreign injunctions and racial distortions. Through his work and his engagement, he embodies the scholarly resistance of a rooted, autonomous and universalist muslim Africa.

A pivotal figure of west african islam

If one were to embody, in a single figure, the final brilliance of sahelian scholarly civilization, it would undoubtedly crystallize in the person of Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī. Born into an illustrious lineage of Timbuktu ulema, trained within the demanding circles of maliki thought, and deported by the saadian dynasty to the Maghreb, this intellectual was both a product of his time (that of the songhai collapse) and a witness to the former grandeur of islamized western Sudan.

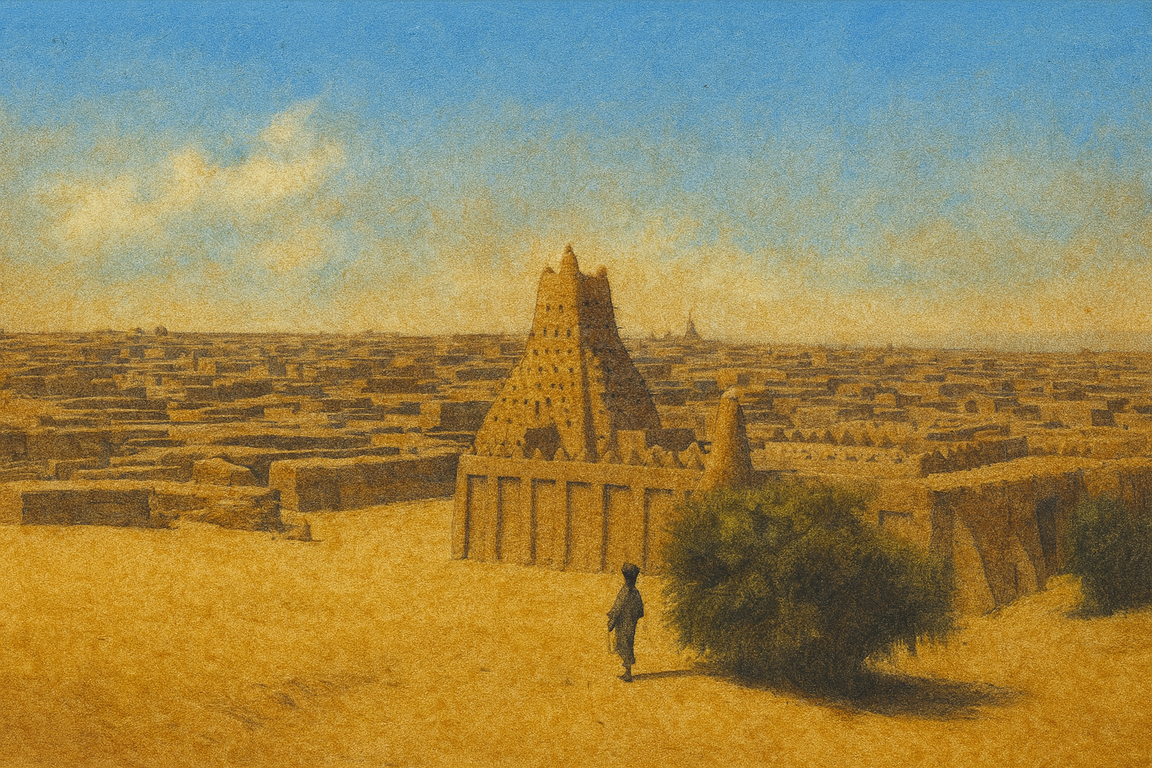

Timbuktu, in the sixteenth century, was no longer the effervescent crossroads of Mansa Musa or Askia Muhammad, but it nevertheless remained an intellectual bastion where religious sciences, law, logic, medicine and arabic letters were transmitted. In this city of the inner Niger delta, situated at the intersection of trans-saharan trade and sahelian clan solidarities, Ahmad Bābā emerged as the last great spokesperson of an endogenous and demanding tradition.

His work, vast and still insufficiently studied, attests to a deep grounding in maliki fiqh corpora, but also to a determination to affirm the dignity and intellectual competence of black peoples in the face of racial prejudices, sometimes present even in religious discourses imported from the Maghreb. In this sense, he was as much a scholar as a resister, wielding the pen where others raised the sword.

But this resistance was ambivalent. For while Ahmad Bābā opposed the humiliation of songhai elites by the Moroccan conquerors, he never fundamentally challenged the established order. If he criticized the ignorance of saadian governors, he did not contest their monarchical legitimacy. If he defended black Muslims against enslavement by assimilation, he nonetheless justified the enslavement of african pagans. This is the full complexity of a thinker rooted in an era of rupture.

At once guardian of ancient knowledge and actor in a world turned upside down, Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī embodies one of the final glimmers of a sovereign african intellectual tradition, islamized but not alienated, scholarly yet rooted, with Timbuktu as its gravitational center. This study is devoted to rediscovering this man, his work and his time.

The lineage of a sahelian faqih

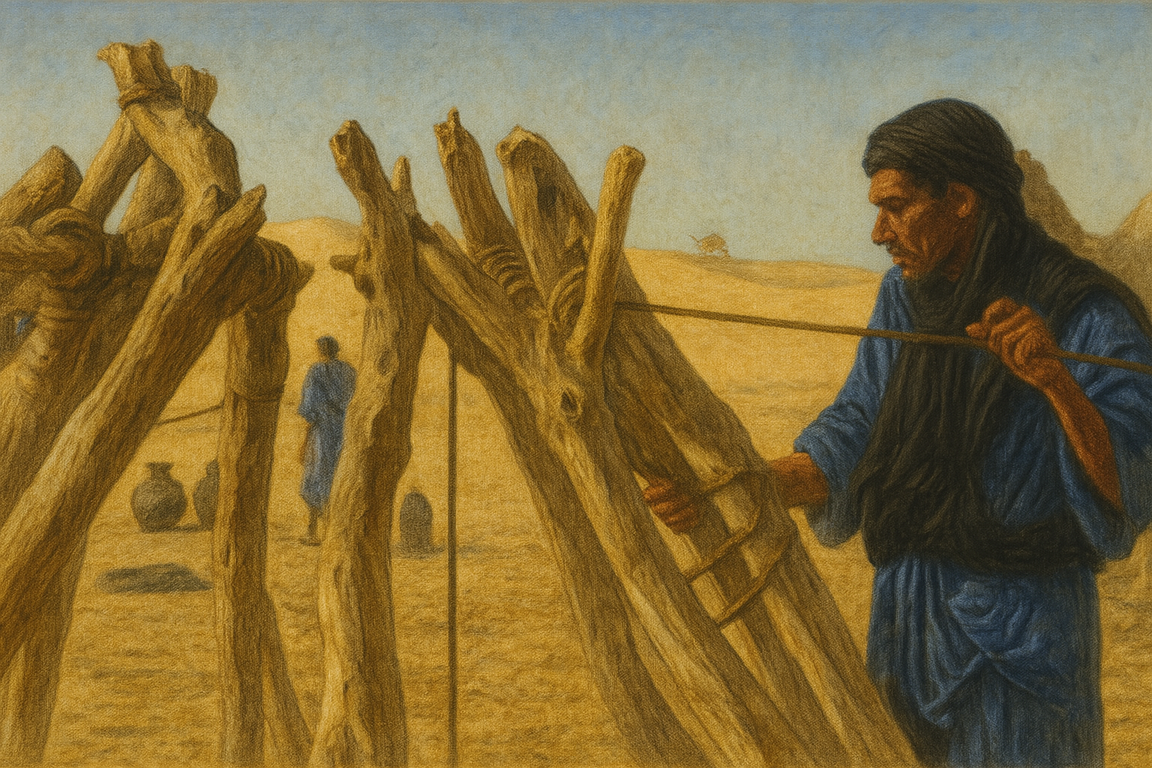

It was in 1556, in the saharan oasis of Araouane, on the edge of the desert and the inner Niger delta, that Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī was born. This modest caravan transit post north of Timbuktu immediately symbolizes the future scholar’s anchoring in the geographical dynamics linking the sahelian world to the great trans-saharan trade circuits.

Born into the Aqīt family, Ahmad Bābā belonged to Timbuktu’s intellectual aristocracy. This lineage, of sanhaja berber origin, had established itself since the fifteenth century as the core of the city’s ulema. Its members continuously held positions as qadis (judges), imams and professors in the mosque-universities, exercising authority over textual mastery and the purity of maliki orthodoxy.

From a young age, Ahmad Bābā was thus immersed in a universe of erudition, austerity and prestige. His father, Ahmad bin al-Hajj Ahmad bin Ahmad Aqīt, taught him the first foundations of the Qur’an, the arabic language and islamic sciences. But the true turning point of his education occurred under the guidance of Shaykh Mohammed Bagayogo, himself descended from the noble lineage of Djenné and one of the greatest jurists of his time. Under this demanding master, young Ahmad sharpened his reasoning skills, developed a strong taste for scholarly disputation (munāzara), and gained access to the most complex corpora of muslim law.

At an age when others struggled to memorize a few verses, Ahmad Bābā had already assimilated the foundations of maliki fiqh, tafsīr (Qur’anic exegesis), usūl al-fiqh (legal theory), mantiq (aristotelian logic adapted to islam), as well as arabic grammar and rhetoric, essential keys to textual interpretation. This rigorous intellectual base, forged in the halls of the Sankoré mosque and in family majlis, prepared him to embrace the destiny of a mujtahid, an authorized interpreter of scriptural sources.

Thus, far from being an autodidact or an inspired marginal, Ahmad Bābā embodied the archetype of the classical sahelian scholar: born into a great house, steeped in tradition, rooted in a milieu where knowledge is a hereditary vocation. His future authority, both juridical and moral, derived its full legitimacy from this lineage and early discipline.

Timbuktu at the end of the sixteenth century

In the final third of the sixteenth century, Timbuktu, once the radiant jewel of the songhai empire, had become a coveted and wounded territory, torn between imperial memory and the intrusion of a foreign power. In 1591, the Moroccan invasion launched by the saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur brutally ended the political independence of western Sudan. The occupying army, commanded by Pasha Judar, a Spanish renegade converted to islam, crushed the songhai forces at the battle of Tondibi, triggering the collapse of an imperial order which, though weakened, had still structured the region’s political and commercial balances.

The arrival of the Moroccans in Timbuktu, under the pretext of restoring a supposedly pure islamic order, in reality marked the beginning of a period of systematic plunder, authoritarian centralization and repression of learned elites. The ulema, long holders of moral and juridical authority, were now perceived as obstacles to a disguised colonial domination. Ahmad Bābā, already an eminent scholar respected for his doctrinal authority, was accused of sedition, suspected of inciting disobedience against the occupier and of attempting to preserve a degree of local jurisprudential autonomy.

This suspicion led to a wave of indiscriminate arrests. In 1594, Ahmad Bābā was deported to Fez, chained alongside several dozen other scholars, in what remains one of the most dramatic episodes of Timbuktu’s intellectual memory. The official justification of the Moroccan authorities—ensuring the purity of maliki doctrine—barely concealed a policy of eliminating scholarly counter-powers guilty of defending an african islamic identity misaligned with the Maghreb.

Under saadian domination, Timbuktu thus entered an ambiguous era: an occupied city yet still a center of knowledge; a commercial hub stripped of autonomy yet still connected to caravan networks; a citadel of manuscripts emptied of its most eminent masters. The banishment of Ahmad Bābā, far from extinguishing him, paradoxically consecrated his role as the moral conscience of literate islamic Africa and inaugurated a fertile exile.

Exile in Fez (1594–1608)

Torn from his homeland and conducted under guard to Fez, Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī could have become just another political prisoner, broken by exile and chains. This was not the case. In this Maghrebi intellectual capital, where the most sophisticated schools of islamic thought converged, the sudanese scholar asserted himself.

During his fourteen years of captivity, Ahmad Bābā transformed disgrace into an exercise of memory and scholarly authority. He authored more than forty works covering a wide range of disciplines: fatwas addressing complex jurisprudential cases, treatises on maliki law, works of logic and grammar, as well as precious hagiographic biographies celebrating key figures of west african islam. In these writings, methodological rigor rivals stylistic elegance, and sunni orthodoxy never excludes local rootedness.

Among his major works is Nayl al-ibtihāj bi-taṭrīz ad-dībāj, an intellectual biography of Muhammad al-Maghīlī, the north african theologian who had introduced a rigid form of maliki islam into sahelian black societies in the fifteenth century. By paying homage to this indirect mentor, Ahmad Bābā affirmed his belonging to a trans-saharan tradition of orthodoxy while correcting certain doctrinal excesses. The work is both a manifesto of sunni fidelity and an assertion of african intellectual sovereignty.

But it is above all on the slippery terrain of the “racialization of slavery” that Ahmad Bābā articulated his boldest reflections. He vehemently opposed the idea, widespread in certain Maghrebi circles, that skin color constituted a criterion of servitude. He explicitly rejected the biased interpretation of the “curse of Ham,” used to justify the enslavement of black people. For him, only religious unbelief—and not race—could justify enslavement under islamic law. This position, both courageous and ambivalent, makes him a precursor of islamic anti-racist thought, even though it did not challenge slavery as an institution.

In sum, far from being a dark interlude, Ahmad Bābā’s exile in Fez consecrated his influence beyond the Sahel. He earned the respect of Morocco’s greatest jurists and left behind a body of work that continues to nourish african muslim intellectual circles today. His pen, sharpened by trial, became the weapon of an african scholar— islamized but not subordinated, faithful to his tradition and lucid about the dangers of ignorance and prejudice.

Return to Timbuktu (1608)

After fourteen years of exile and enforced scholarship in the Maghreb, Ahmad Bābā was finally authorized to return to his sahelian homeland. The decision came from the saadian sultan Zaydan an-Nasir, successor to Ahmad al-Mansur, who sought to ease tensions with southern ulema and pacify the region through measured integration of local religious elites. Thus, in 1608, Ahmad Bābā re-entered Timbuktu as a master consecrated by trial and knowledge.

His return was greeted with fervor by the scholarly community. His peers, former students and mosque scholars welcomed him as a faqih returned from a long initiatory journey, strengthened by his intellectual struggle against ignorance, arrogance of power and racial prejudice. Teaching circles (halaqāt) quickly reorganized around him. He taught fiqh, exegesis, logic and biography, transmitting to younger generations the fruits of his Moroccan labor while rehabilitating the methodological foundations of sahelian maliki thought.

Yet this intellectual renaissance unfolded within a profoundly altered context. The songhai political framework had collapsed, and saadian domination, though weakened, remained present through the pashas installed in Timbuktu and dependent on Marrakech. Ahmad Bābā, despite his immense moral prestige, remained under surveillance, as his positions—though not openly subversive—implicitly asserted intellectual and religious autonomy.

Indeed, Ahmad Bābā assumed a true spiritual magistracy. In a climate of instability and suspicion, he sought to reconstruct a structured scholarly order based on ancient learned families, preserved manuscripts and the authority of Qur’anic schools. His work and posture expressed the will to maintain african doctrinal sovereignty without dissolving into political injunctions from the north.

The task was immense: political structures were fractured, commercial circuits disorganized, and clan rivalries inflamed by the weakness of central power. Nevertheless, Ahmad Bābā endured until his death in 1627, in a city transformed yet still illuminated by his knowledge.

He left behind a corpus of manuscripts, a revived teaching tradition and a respected memory that would endure within the Aqīt family and beyond. In this sense, he remains the final great symbol of a literate, rooted and intellectually independent muslim Africa—a figure whose return consecrated not only a man, but a civilization on the brink.

An islamic critique of racism

One of the most fascinating—and controversial—facets of Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī’s thought lies in his reflections on slavery and race at a time when the sahelian-maghrebi world experienced an intensification of captive exchanges through both jihad and trans-saharan trade networks. A scrupulous jurist faithful to the maliki school, Ahmad Bābā nevertheless emerged as a critical thinker confronting racialist distortions infiltrating islamic legal practice.

In his writings, particularly his fatwas on slavery, he established a fundamental distinction: the criterion of slavery is not skin color, but religious status. In other words, no black person could be enslaved if muslim. This assertion, juridically elementary, acquired particular resonance in a context where many arab-berber traders abusively equated “black” with “slave,” following an implicitly racialist logic.

Ahmad Bābā thus attacked, with rare firmness for his time, the pseudo-religious justification of anti-black racism, notably the invocation of the “curse of Ham,” a biblical theory falsely identifying sub-saharan Africans as Ham’s descendants destined for servitude. He rejected this notion as alien to islam, denouncing a racialized reading of sacred law that corrupted its universal meaning.

However, this courageous stance should not be idealized beyond its doctrinal framework. Ahmad Bābā did not challenge slavery as an institution. On the contrary, he defended it as legitimate for non-muslims captured through jihad or born outside dār al-islām, in accordance with the orthodoxy of his time. In his texts, legal protection thus rested solely on islamic affiliation, not on universal humanitarian principles.

This contradiction—between explicit critique of racism and implicit adherence to confessional slavery—illustrates the intellectual complexity of a man torn between fidelity to fiqh and sensitivity to the socio-political realities of his era. Ahmad Bābā was, in essence, an ethical regulator of the islamic slave system, concerned with preserving the honor of black Muslims in a world increasingly tempted by racial instrumentalization.

This position, though limited in emancipatory scope, remains historically crucial, as it laid the foundations for an islamic anti-racial discourse later taken up by african muslim reformers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Legacy, posterity and appropriation

The legacy of Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī extends far beyond the temporal confines of his century. Upon his death in 1627, the faqih of Timbuktu was celebrated by his peers as a mujaddid, a renovator of islam, a prestigious role attributed to one destined to restore doctrinal purity at the turn of each hijri century. This recognition was not merely rhetorical: within sahelian scholarly circles, his name was inscribed in the pantheon of great maliki jurists alongside Ibn Rushd or Khalīl.

His intellectual canonization within Timbuktu’s learned traditions occurred through a dual process. On the one hand, scholarly families integrated his works into Qur’anic teaching cycles. On the other, scribes and copyists ensured their continuous reproduction, making Ahmad Bābā not only a thinker but a living pillar of sahelian manuscript memory.

This organic bond between his thought and african written culture was magnified by the creation, in 1973, of the Ahmad Baba Institute of Timbuktu, whose collections now hold more than 18,000 manuscripts from mosques, private libraries and family archives. The institute does more than honor his name: it extends his vocation through preservation, digitization and transmission of west african intellectual heritage. During the islamist attacks of 2012–2013, this legacy was endangered but defended with exemplary courage by Timbuktu’s inhabitants, determined to protect the work of their “imam of knowledge” against new iconoclast barbarism.

Yet Ahmad Bābā’s legacy is not confined to scholarly circles. It is appropriated, interpreted and sometimes reinvented in light of contemporary issues. In debates on “black islam,” human rights and the critique of racism in muslim societies, his name is frequently invoked as a symbol of an islamized, educated and resistant Africa. His critiques of racial prejudice are mobilized as anti-colonial and anti-slavery arguments, while his defense of islamic law underscores the juridical autonomy of sahelian societies vis-à-vis modern ideological imports.

This appropriation is nonetheless ambivalent. Ahmad Bābā was both a humanist thinker in his struggle against racism and a conservative jurist in his rigid defense of confessional social order, including justifications of non-muslim slavery. This tension is not an obstacle to understanding his thought—it is its very core. Ahmad Bābā embodies the complexity of a saharan intellectual world capable of combining juridical rigor, local rootedness and global reach.

He stands, in this respect, as the ultimate watchman of a sahelian golden age whose tutelary shadow still hovers over manuscripts, mosques and consciences.

The watchman of the desert and the faith

Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī remains one of the last giants of an era when west Africa, far from clichés of marginal alterity, shone within the islamic world through its scholars, manuscripts and intellectual autonomy. Heir to great sahelian traditions and artisan of a rooted islam, he was both guardian of an ancient order and precursor of critical consciousness. Neither rebel nor subordinate, he embodied the rare figure of a free scholar bound only to his principles.

His work, written between chains and lecterns, teaches that in troubled times the pen may rival the sword, and that the truth of law can challenge the arbitrariness of the powerful. If posterity honors him, it is because he upheld african dignity in the most learned circles while reminding that black islam, far from being a periphery of the umma, is one of its spiritual lungs.

In the sands of Timbuktu, the wind has not erased his name.

It has engraved it.

Sources

Timothy Cleaveland, “Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī and his Islamic Critique of Racial Slavery in the Maghrib”, Journal of North African Studies (2015).

Oxford Research Encyclopedias – Ahmed Bâba al-Timbuktî.

John O. Hunwick, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire (Brill, 1999).

“Timbuktu Scholarship: But What Did They Read?”, Journal of the History of Ideas.

Robin Walker, The Manuscripts and Intellectual Legacy of Timbuktu, Gresham College.

Wikipedia (fr/en) — Ahmad Bābā al-Timbuktī; Institut Ahmed-Baba; Manuscripts of Timbuktu.

Contents

A pivotal figure of west african islam

The lineage of a sahelian faqih

Timbuktu at the end of the sixteenth century

Exile in Fez (1594–1608)

Return to Timbuktu (1608)

An islamic critique of racism

Legacy, posterity and appropriation

The watchman of the desert and the faith

Sources