We think we know Rosa Parks. A woman, a bus, a refusal. But behind this gesture, turned into myth, lies a life of struggle, strategy, and courage. Far from the frozen image of a docile icon, Rosa Parks was a formidable activist—trained, connected, and determined. Her refusal on December 1, 1955 was not an isolated act of defiance, but the result of years of silent battles and collective tactics. This is the true story, complete and political; that of a woman who never stopped resisting.

Montgomery, Alabama. December 1, 1955.

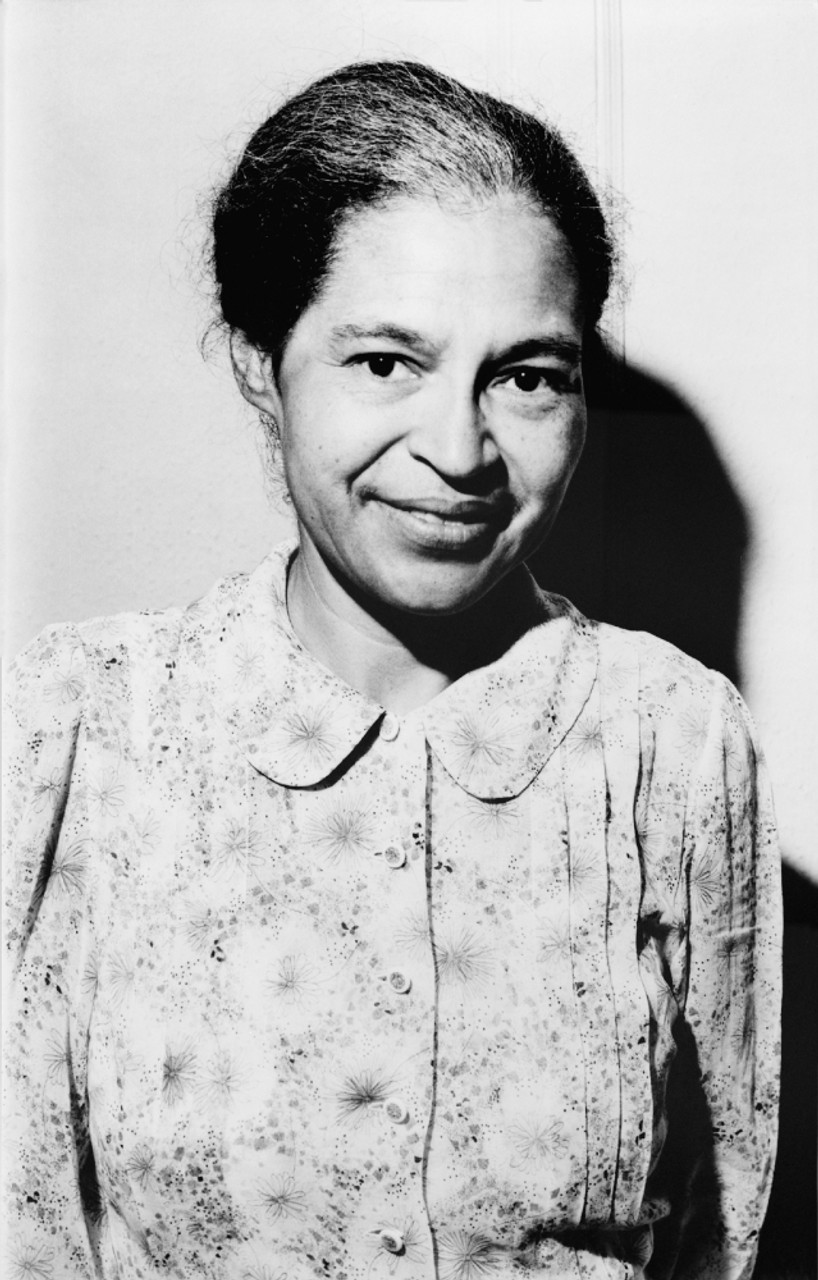

The bus engine growls in the dim light of a winter afternoon. Leather seats creak under the weight of a segregation that has become ordinary. On seat 11, a Black woman, 42 years old, a discreet seamstress, sits where she is not supposed to. The driver, James F. Blake (a regular purveyor of public humiliations), orders her to stand. She refuses. And History changes course.

That day, in the stifling confines of a municipal bus, the entire racial structure of the Southern United States cracks.

But to understand the significance of that refusal, one must plunge into postwar America: a republic victorious over Nazism, yet incapable of guaranteeing equality on its own soil. In Alabama, as elsewhere in the Deep South, Jim Crow laws codified an American-style apartheid: segregated public benches, unequal schools, unpunished lynchings, and compartmentalized transportation. Black bodies were controlled, displaced, and often crushed—symbolically as much as physically.

In this landscape of legal violence and institutional silence, Rosa Louise Parks enters the scene. Not as a grandmother suddenly tired of walking (as the sanitized narrative of school textbooks likes to repeat), but as a seasoned activist, a strategist, fully aware of the political theater in which she was acting.

See more

What if Rosa Parks was not “tired” that day, but strategically ready?

What if the courage to remain seated was less an impulse than the culmination of a struggle already underway?

In the limbo of a racially fractured South

Born Rosa Louise McCauley in 1913 in Tuskegee, in the heart of Alabama, the little girl whose calm posture of refusal History remembers was first inscribed in a complex map of bloodlines and belonging. At the crossroads of worlds, her family tree blended sub-Saharan Africa, Cherokee lands, and Northern Ireland via the Scots of Ulster. A dissonant, composite genealogy that alone embodies the founding violence of the Americas: the rape of enslaved women, the erasure of Native peoples, white settlers in search of “virgin” land.

The mixed heritage of Rosa Parks was nothing like folkloric identity. It was a memorial burden, a painful memory embodied. Her maternal grandmother, Rose Edwards—daughter of an enslaved woman and an Irishman—was the emotional and spiritual pillar of her childhood. Beyond the name, she transmitted the moral strength of subaltern lineages: a strength made of quiet dignity, intimate refusals, and domestic insubordination; that of women who remain silent yet teach.

Her grandfather, meanwhile, stood guard, rifle in hand, on the family porch, watching for the nocturnal processions of the Ku Klux Klan. For in this America of the first half of the twentieth century, Black people did not live only under the threat of institutional contempt; they lived in the tangible, physical fear of arbitrary hanging. Far from passive figures or defenseless victims, the McCauley family formed a cell of resistance ahead of its time—a kind of domestic fortress in the midst of hostile territory.

It is therefore no surprise that Rosa Parks developed early a sharp awareness of the “double world” in which she lived: that of Whites—vertical, dominant, confident in its laws; and that of Blacks—lateral, defensive, forced into invisibility. She experienced this divide during her school journeys, watching each morning as buses carried white children away while she and her peers walked through the red dust of the rural South. America offered her its racial geography from her very first steps.

Before attending school desks, Rosa Parks was first the silent pupil of her mother, Leona, a trained teacher and committed activist. After her parents’ divorce, it was in the confined but rigorous space of her mother’s home that Rosa learned to read, write, think—and resist. Education there was not merely instruction; it was the transmission of a moral code, a sense of struggle. Every lesson became an act of faith in Black dignity, in a world built to deny it.

It is therefore no accident that Rosa Parks was literate before ever wearing a school uniform. And when she entered the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, an institution founded by abolitionist missionaries from the North, she encountered a double lesson: academic knowledge on one side, and the hatred in return of those who could not tolerate young Black girls receiving an education. Twice, the school was burned down by local Klan henchmen. Ashes as report cards.

But violence is not always spectacular. It can be muffled, insidious, daily. Rosa recalled that in public places, the water from the “Whites Only” fountains seemed to taste better—not because she had drunk it, but because prohibition itself made it desirable. At seven years old, this perception was not naïve; it was the realization that the world was not neutral, that it was divided into privileges and codified humiliations.

On buses, humiliations became ritualized. Black children had no school transportation. Adults had to pay at the front, get off, then re-enter through the back—when the driver did not simply close the doors and leave them behind. A scene that, in 1943, nearly escalated when Rosa already clashed with the same James Blake, the driver she would confront twelve years later. That day, he expelled her like an undesirable. She walked eight miles in the rain, alone, but determined never to submit again.

In this childhood marked by maternal pedagogy and structural brutality, there was an invisible threshold—what Rosa Parks would later call the boundary between submission and consciousness. Many Black Southerners had resigned themselves to surviving on the margins. Rosa learned instead to read there the fundamental lie of the American “living together.”

And slowly, very slowly, an idea took shape: that acceptance can become complicity. That refusing is not a heroic choice, but a moral necessity.

An activist, a strategist, a woman

Contrary to the frozen image of a seamstress “caught off guard” by History, Rosa Parks did not stumble into dissent by accident. Her gesture on December 1, 1955 was neither impulsive nor isolated: it was the result of years of patient, discreet, but deeply structured engagement.

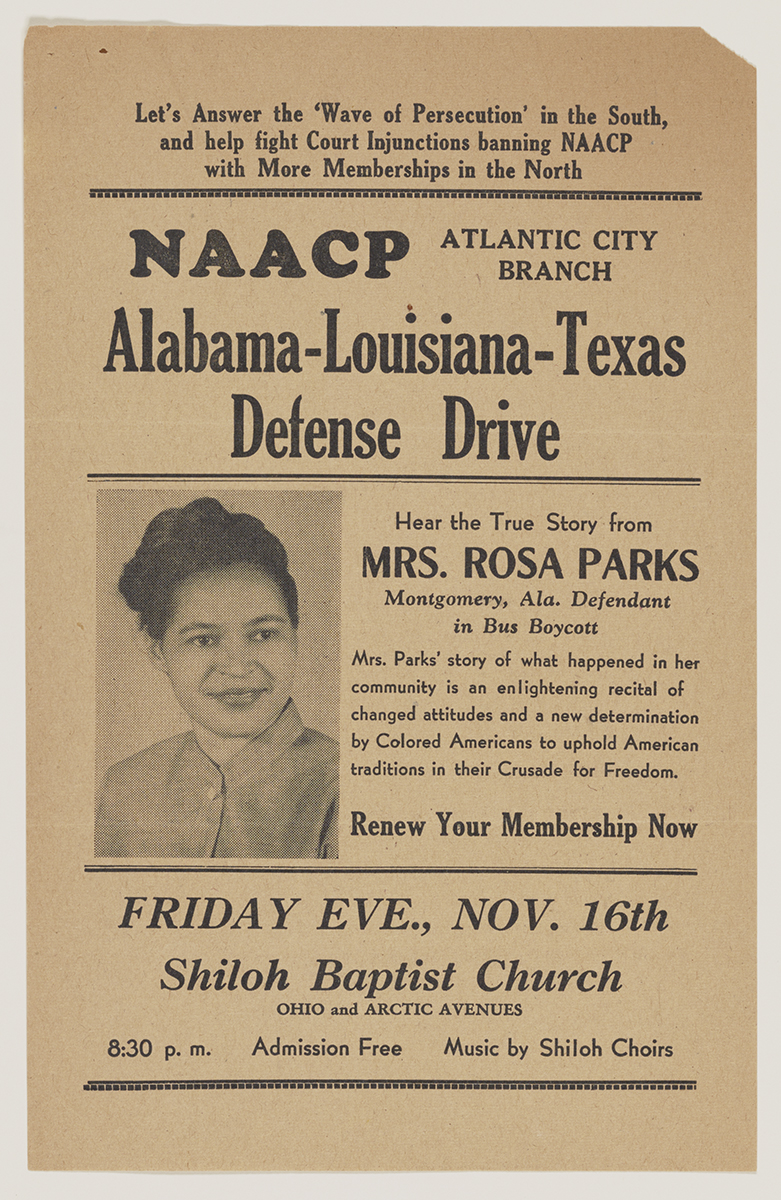

As early as 1943, she joined the Montgomery branch of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), then at the forefront of legal defense for African Americans. She was initially confined to the position of secretary—an administrative role, modest in appearance. But in a patriarchal South, where even Black men struggled to assert themselves, the status of a Black woman activist remained subordinate. Yet she held her ground with constancy and determination, meticulously recording meetings, organizing memberships, listening to accounts of brutality. This secretarial post became a strategic observation post.

The following year, 1944, Rosa Parks was sent on assignment to Abbeville, Alabama, to investigate a case that shook Black consciousness: the gang rape of Recy Taylor, a young Black factory worker, by seven white men. None were prosecuted. The case, smothered by the authorities, brutally revealed white impunity in the South. Rosa investigated, interviewed, gathered evidence, and passed the information to the press. Outrage spread nationwide, but justice remained blind. For Rosa, it was a turning point: the intuition that institutions protect only those they choose to consider citizens.

This same turning point led her to another circle of resistance: a white couple, Clifford and Virginia Durr—progressive lawyers, close to the New Deal, and rare figures of white allies in a hostile South. They recognized in Rosa not a useful subordinate, but a lucid conscience. They encouraged her to attend a training session at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, a center of popular education then under surveillance for its radical ideas. There, Rosa Parks discovered other struggles: those of workers, miners, trade unionists. She understood that the Black question was not isolated; it lay at the heart of a global system of oppression.

This period was not a mere “preface” to her act of civil disobedience. It was its framework. It shows that Rosa Parks was never a simple victim, but a methodical activist—strategically trained, socially connected, ideologically armed.

It is therefore time to reconsider the conventional image of the “tired old lady.” In 1955, Rosa Parks was neither naïve nor spontaneous. She was ready. History did not seize her in passing; she seized it with composure.

Popular history loves clear beginnings, solitary heroines, symbolic gestures. But Rosa Parks was neither the first nor the only one. Nine months before she refused to give up her seat, Claudette Colvin, a 15-year-old teenager, had already defied the same system in Montgomery. Handcuffed, brutally expelled from a bus, Colvin invoked her constitutional rights while shouting in the police station: “It’s my freedom you’re violating.” Yet her case was set aside. Why? Too young, too outspoken, and above all—pregnant by a married man. A moral transgression deemed unacceptable for a Black community anxious to present an “irreproachable plaintiff.” Rosa Parks, by contrast, was a married, stable, Christian, discreet woman. A respectable figure. And, crucially, an activist already embedded in the networks.

This choice, far from a coincidence, reveals the political strategy of the movement. Rosa Parks was not propelled by chance; she was selected. She embodied both internal moral order and controlled revolt. An activist experienced enough to withstand police pressure, yet dignified enough to carry the fight into courtrooms and the media. She was, quite literally, the defensible figure.

At the same time, her job at a desegregated military base—Maxwell Air Force Base—exposed her to another possible world. There, neither cafeterias nor internal transportation were subject to Jim Crow laws. This coexistence, relative but real, acted on Rosa as a revelation: segregation was not natural; it was political—and therefore reversible. It was at Maxwell that the idea took root that oppression could be challenged, and that refusal, even individual, could shake the established order.

Added to this was another dimension, less known but essential: yoga. Rosa Parks practiced it from the 1950s, long before it became a bourgeois trend. For her, it was not a leisure activity but a tool of bodily mastery, stress management, and moral centering. In her memoirs, one discovers a woman for whom breath and inner calm were forms of resistance. She later even taught this discipline, within her institute, to young activists—combining postures, memory of struggles, and civil rights education.

Thus, long before the famous boycott of December 1955, Rosa Parks was already in motion—physically, intellectually, and spiritually. What she accomplished that day on the bus was not a rupture, but a culmination. A decision born of a long inner journey, made of disillusionments, trainings, micro-struggles, and a daily practice of self-mastery.

Nothing in her gesture was improvised. Everything, on the contrary, was already written.

The gesture, the arrest, the organized revolt

It was not a stranger Rosa Parks confronted on December 1, 1955. It was not a mere overzealous driver enforcing unjust laws. It was James F. Blake, the same man who, twelve years earlier, had already tried to humiliate her publicly. In 1943, Rosa boarded his bus, paid at the front as required, but instead of getting off to re-enter through the back—this humiliating gymnastics imposed on Blacks—she moved directly toward the rear. Blake exploded. He shouted, threatened, hand on his gun. Rosa was expelled. The bus pulled away, leaving her alone in the rain. Eight miles on foot. A bitter walk, soaked in cold anger. That day, something broke—and perhaps, something also formed.

For Parks, Blake embodied the daily brutality of segregation. Not the hooded Ku Klux Klan, not the racist judge in robes, but the banal functionary of American apartheid: an ordinary white man, invested with a small power, determined to remind Blacks of their place.

So in 1955, when Rosa boarded that bus in Montgomery and saw Blake at the wheel, she knew. She recognized him. She also knew what would follow. And this time, she stayed seated.

Some convenient narratives will say she was “tired.” Physically, perhaps. But fundamentally, she was ready—long prepared. Her refusal was not an outburst of exhaustion, but a meticulously matured act; the convergence of a decade of struggles, trainings, readings, digested humiliations, and learned strategies.

In her memoirs, she wrote:

“I was not tired of walking; I was tired of giving in.”

And she did not give in. Blake called the police. Rosa did not resist arrest, but she did not collaborate either. She was calm, determined, unshakable. At that precise moment, it was no longer James Blake who held the power. It was she—who orchestrated the scene, who set the tempo. She had just triggered a mechanism that no white driver would be able to defuse.

The arrest of Rosa Parks, in itself, might not have been enough to trigger a national movement. Others before her had refused injustice—Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Mary Louise Smith—but none of these acts had yet found the right resonance. What was needed was a conjunction: a legitimate figure, seasoned militant relays, and a context ripe for the crystallization of Black anger.

From her cell, Rosa Parks called Edgar Nixon, leader of the local NAACP, a tenacious trade unionist and veteran of civil rights struggles. Nixon immediately understood that the event went beyond a simple incident. He, in turn, called Clifford Durr, a progressive white lawyer and defender of lost causes in a South hostile to seekers of justice. Durr agreed to represent Parks. The chain was set in motion. The case moved beyond the penal framework. It became political.

That very evening, rumors spread through Montgomery. Activists gathered. The Black community, which made up the majority of public transport users, had been seething for years over the humiliations imposed by the municipal bus company. Rosa Parks became the catalyst of this collective frustration. But for mobilization to last, structure was needed.

This is where a young pastor, still little known beyond his circle, emerged: Martin Luther King Jr. He was only 26, newly arrived in Montgomery, and preached at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. His eloquence captivated, his bearing reassured. He was appointed president of the newly created organization formed in urgency: the Montgomery Improvement Association.

The boycott was declared. No loud demonstrations, no violence: a massive abstention. African Americans, who represented 75% of bus customers, decided to walk, organize solidarity taxis, and boycott until concrete gains were achieved. Three simple but decisive demands were formulated:

- The freedom to sit anywhere, according to the rule “first come, first seated.”

- More respectful drivers toward all passengers, regardless of skin color.

- The hiring of Black drivers in African American neighborhoods.

The boycott lasted 381 days. The city was paralyzed. Economic losses accumulated, judicial pressure mounted, the homes of King and Nixon were bombed. But the mobilization held. The world watched. Telegrams of solidarity poured in from Europe, India, and Harlem. The local struggle became a universal symbol.

And Rosa Parks, in this machinery, remained the initial flame. Without fiery speeches, without spectacular charisma. Just a woman seated on a bus, refusing erasure.

Rosa Parks, the woman behind the icon

History loves heroines, but rarely treats them with gratitude. Once the flashes fade, the name Rosa Parks becomes a totem; her body, however, remains vulnerable. In Montgomery, her life became impossible. Threatened, harassed, blacklisted by white employers and even marginalized by some Black activists for having “stolen the spotlight,” she was forced, with her husband Raymond, to leave Alabama. It was not an ascent, but an exile.

Destination: the industrial North, more precisely Detroit, Michigan. A working-class city, an emerging African American stronghold, yet still riddled with subtler social segregations. There, she encountered poverty, unemployment, loneliness. She worked for a time as a seamstress, returning to basics—fingers on the sewing machine, mind full of bitter silences. The icon had no income, no status, no protection.

Then came a decisive meeting: John Conyers, a young lawyer and later African American congressman. He hired her as a parliamentary assistant in 1965. Rosa Parks entered the corridors of power—not to glorify herself, but to continue, quietly, the struggle for civil rights. She worked there until her retirement in 1988. Thirty years of labor, often in the shadows, always coherent.

This post-boycott trajectory reveals a harsh truth: liberal societies love to sanctify their dissidents—on the condition that they then remain silent. Rosa Parks never did. Even ignored, she never turned away from the struggle—for youth, for political prisoners, for the most deprived.

Exile did not break her. It freed her from institutionalization. The icon went into exile; the activist remained standing.

From the earliest months of the boycott, the image of Rosa Parks escaped Rosa Parks. Photographs circulated, speeches praised her, politicians cited her. She was made into a secular saint, the “mother of the civil rights movement.” Yet what was retained of her was often frozen: a woman seated, calm gaze, purified gesture. The icon eclipsed the individual, and history became decorative.

American media, hungry for simple, consumable figures, reduced her gesture to an act of passive dignity. Rosa became a reassuring symbol for white consciences: not violent, not loud, not radical. Her NAACP engagement, her investigation into Recy Taylor, her links to socialist circles, her attendance at the Highlander School were erased. The legend remained: a tired old woman who just wanted to sit. She was sanctified in order to be neutralized.

Faced with this confiscation, Rosa Parks decided to speak again. In her books (notably My Story and Quiet Strength), she restored her version of the narrative, with lucidity and gravity. She spoke of her faith, her commitment, her anger. She corrected the record:

“I was not old; I was 42. I was not tired of walking; I was tired of submitting.”

Her words deflated the myths. She also affirmed that the arrest was not an accident, but a considered decision.

Yet despite these clarifications, Rosa Parks remained alone. Her iconic status did not come with material support. She eventually lived with difficulty, was the victim of a burglary in 1994, fell ill, and was threatened with eviction for unpaid rent. The American state granted her symbolic honors—but few means. The public aura barely masked militant solitude, the harshness of the post-revolt years, the feeling of abandonment.

For behind every statufied figure lies flesh. Behind every myth, a betrayed memory. Rosa Parks, long before being an icon, was a strategist, an activist, a lucid woman—and often alone.

Rosa Parks, captured icon or active fighter?

The paradox of Rosa Parks is that she was long forgotten, then suddenly omnipresent. Today, she is everywhere. Her name adorns high schools, avenues, tram stations. Her silhouette, frozen on a bus bench, stands in museums. A Barbie in her likeness was even launched by Mattel, presenting her as a smooth, inspiring universal heroine. Rosa Parks has become a brand.

This memorial explosion is not neutral. It is part of a well-oiled process by which liberal societies integrate dissident figures to neutralize their subversive potential. By turning her into a statue, she is rendered harmless. By celebrating her, one forgets that she was long fought, ignored, marginalized. Museification produces consensus, not memory.

But what is often honored is not Rosa Parks; it is an edited version of her. A gentle, composed, almost depoliticized woman. The image has become more convenient than the commitment. It allows institutions, brands, and elected officials to cloak themselves in a comfortable memory: that of a moral victory already achieved, without rough edges or conflict.

Yet Rosa Parks never ceased to be radical. Her engagement went far beyond refusing to give up a seat. She advocated for political prisoners, for Black youth, for prison reform. She criticized American imperialism, denounced structural racism, supported controversial figures. Her legacy, if taken seriously, would be unsettling.

But official history prefers saints to fighters. And so Rosa Parks was gradually absorbed, polished, sanitized. By commemorating her gesture endlessly, her struggle is forgotten. By speaking of courage, the structures she denounced are elided.

A question remains open: by multiplying statues and tributes, do we honor Rosa Parks—or do we seek to imprison her forever in the frozen moment of a silent bus?

Where others might have settled for medals and honors, Rosa Parks chose transmission. In 1987, she founded with Elaine Eason Steele the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development—a structure conceived not as a museum, but as a school of consciousness. The goal was not to recount history, but to train heirs. The “Pathways to Freedom” program takes young people to key sites of the civil rights struggle. One learns the past, yes—but above all how to face the future.

This legacy does not stop at the walls of an institute. It infuses current struggles. Rosa Parks is a central reference—not because she “advanced the cause,” but because she showed the method: disobey, resist, embody. She is also claimed by Black feminism, for having long been ignored in favor of great male figures, despite her fundamental role in shaping militant strategies.

Perhaps most avant-garde was her relationship to the body. We now know, thanks to recently explored archives, that she practiced yoga from the 1970s—long before it became a marketing product. She taught postures, stretching, and breathing, notably to young activists—not as wellness, but as political discipline. The body, she said, had to be ready: to resist, to endure, not to give in to panic. In a world where Black people lived in constant hypervigilance, breath became a weapon.

This articulation between spirituality, resistance, and transmission constitutes the true legacy of Rosa Parks. A praxis, more than a memory. A tool, more than a narrative. She never sought to become a monument; she sought to sow seeds.

Rosa Parks did not change History by accident. She confronted it, corrected it, and transmitted it.

Rosa Parks, the irreducible complexity of a refusal

For a long time, Rosa Parks was reduced to a simple gesture: a refusal to stand up. But that gesture, seemingly modest, was in reality an earthquake. It was not just a seat she refused to give up; it was a millennia-old logic of inferiorization, a social organization founded on the obedience of Black bodies, a segregationist order legitimized by law, custom, and fear.

Her “no” was not a pause in reality. It was a tipping point. It emerged at the end of a long, harsh, meticulously constructed path. That day, on that bus, Rosa Parks was neither passive nor tired; she was strategically ready. She knew what she was doing—and for whom she was doing it. Her resistance was neither spontaneous nor solitary: it was historical, rooted, collective.

And yet, History loves shortcuts. It likes to turn struggles into legends, dissidents into icons, strategies into anecdotes. But it is time to return to the true density of Rosa Parks: a radical, organized, committed woman. A woman who understood that revolutions are not born in tumult, but in mastery.

She did not stand up. And that refusal—seemingly inert—made a nation rise.

Notes and references

- Rosa Parks, My Story, trans. from English by Julien Bordier, Libertalia, 2018.

- Rosa Parks & Jim Haskins, Quiet Strength: The Faith, the Hope, and the Heart of a Woman Who Changed a Nation, Zondervan, 1995.

- Rosa Parks, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Montgomery Bus Boycott: Stride Toward Freedom by Martin Luther King Jr., Harper & Row, 1958.

- Claudette Colvin, Twice Toward Justice, Phillip Hoose, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.

- Official biography on BlackPast.

- Complete Wikipedia file (consulted for chronological verification and iconography).

Table of contents

- Montgomery, Alabama. December 1, 1955.

- In the limbo of a racially fractured South

- An activist, a strategist, a woman

- The gesture, the arrest, the organized revolt

- Rosa Parks, the woman behind the icon

- Rosa Parks, captured icon or active fighter?

- Rosa Parks, the irreducible complexity of a refusal

- Notes and references