Discover the horrifying truth of the Parsley Massacre of 1937, where thousands of Haitians were executed under the orders of dictator Rafael Trujillo.

In the dead of night, a single word became a death sentence, and a river turned red, carrying away thousands of innocent lives.

In October 1937, under the ruthless dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, the island of Hispaniola became the scene of an unspeakable human atrocity. The Parsley Massacre — also known as “El Corte” (the cutting) — is one of the darkest episodes in Caribbean history, where racism, xenophobia, and political cruelty combined to lead to the murder of tens of thousands of Haitians and black Dominicans. Under Trujillo’s orders, Dominican soldiers carried out these killings simply because the victims couldn’t correctly pronounce the word “perejil” (parsley) in Spanish.

For a terrifying week, the fertile lands along the border between the Dominican Republic and Haiti were transformed into mass graves, symbolizing the height of human cruelty.

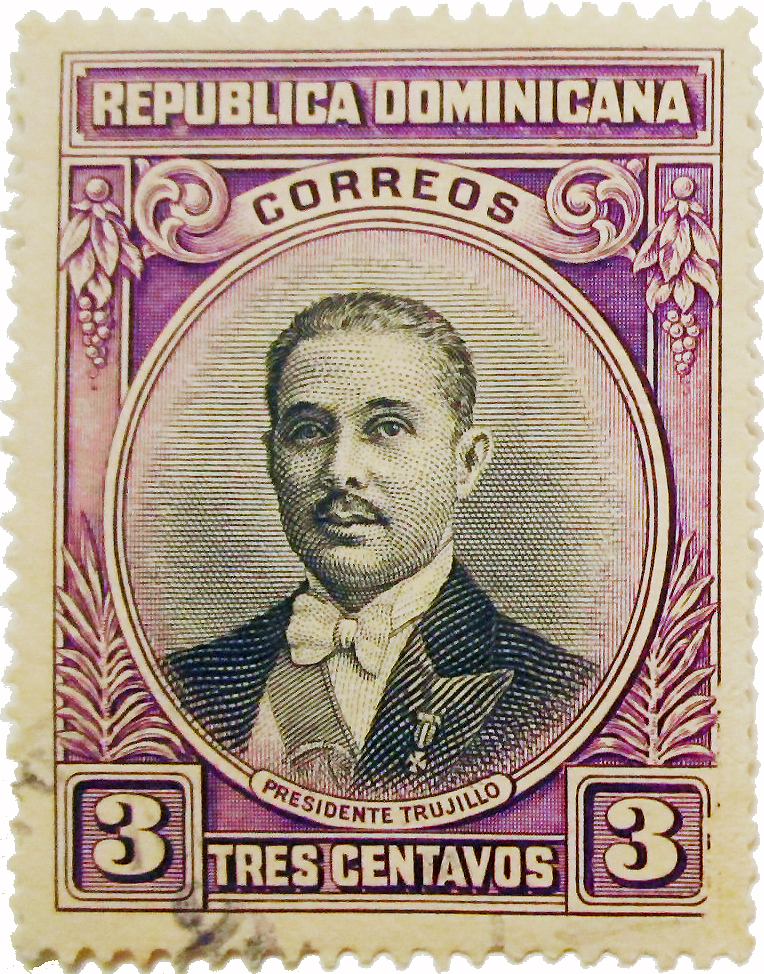

The dark plan of a dictator

Rafael Trujillo, whose name is forever associated with violent nationalism and extreme racial policies, had long harbored a deep-seated hatred for Haitians. His regime promoted an ideology of antihaitianismo, a profound aversion to Haiti and its people, fueled by fear of their African heritage, culture, and supposed illegitimate presence on Dominican land. Trujillo sought to purify Dominican identity, drawing a clear racial line between the two nations sharing the island of Hispaniola.

On October 2, 1937, at a gathering in Dajabón, Trujillo announced his grim plan. In a speech filled with nationalist rhetoric, he declared that the time had come to resolve the “Haitian problem.” A few days later, the massacre began.

A linguistic death sentence

The most terrifying aspect of this massacre lies in its method of identification. Dominican soldiers stopped people suspected of being Haitian and asked them to pronounce the word “perejil.” This simple pronunciation became a matter of life or death. Haitians, whose native languages were French or Creole, struggled to roll the Spanish “r.” Those who failed to pronounce the word correctly were executed on the spot, often decapitated with machetes or shot.

This inhumane linguistic test gave the massacre its infamous name, but it was just one of the many methods used to identify and kill victims. Soldiers roamed villages, rounding up Haitians and black Dominicans, subjecting them to unimaginable violence. Accounts report babies being impaled on bayonets and thrown into rivers.

The blood-stained river

The Dajabón River, a natural border between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, became the symbol of this horror. Dominican soldiers, armed with machetes and guns, chased Haitians into the water, turning the riverbanks into sites of indescribable massacres. Witnesses described how bodies piled up and the blood flowed into the river, staining its waters red for several days.

Survivors who managed to cross the river testified to extreme brutality, where entire families were exterminated. Some were able to swim to Haiti to escape the massacres, but many others were struck down by the relentless violence of the Dominican soldiers.

A calculated genocide

When the killings finally ended on October 8, 1937, estimates of the death toll ranged between 17,000 and 35,000. Entire communities were annihilated, and the Haitian population in the Dominican Republic was decimated. The Dominican regime, under Trujillo, sought to erase all traces of the Haitian presence on its territory. Despite attempts to cover up the atrocities, the massacre drew international attention.

The United States, under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and its “Good Neighbor” policy, opted to push for compensation rather than seek justice. Trujillo eventually agreed to pay Haiti $525,000 (around $30 per victim), a paltry sum in light of the human toll and suffering inflicted.

A hatred that persists

The Parsley Massacre was not just an act of mass murder; it was a deliberate attempt to cleanse the Dominican Republic of its black population. Trujillo aimed to create a whiter and more European nation, and this event left a deep mark on relations between the Dominican Republic and Haiti. This wound, over 80 years old, continues to affect the relationship between the two nations.

The massacre profoundly shaped the history of the two countries that share Hispaniola. Even today, relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic remain tense, often fueled by debates over immigration, identity, and race.

The river remembers

Today, the Dajabón River still flows, but it carries with it the memory of the thousands of lives brutally taken by a dictator’s racial ambition. The Parsley Massacre serves as a painful reminder of the consequences of extreme nationalism and the horrors that can arise when humans are dehumanized because of their skin color or the language they speak.

In both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, this massacre is remembered under different names, but the pain remains the same. For the survivors and the descendants of the victims, the legacy of the Parsley Massacre is not just a historical page; it is a living wound, a reminder of the fragility of human life in the face of hatred.

As the world reflects on this tragedy, one question remains: what have we learned? The river remembers, even if the world forgets.