The Mali Empire, an emblematic civilization of West Africa, is famous for its wealth, its flourishing culture, and its powerful rulers. This empire, which prospered from the 13th to the 16th century, left an indelible mark on world history.

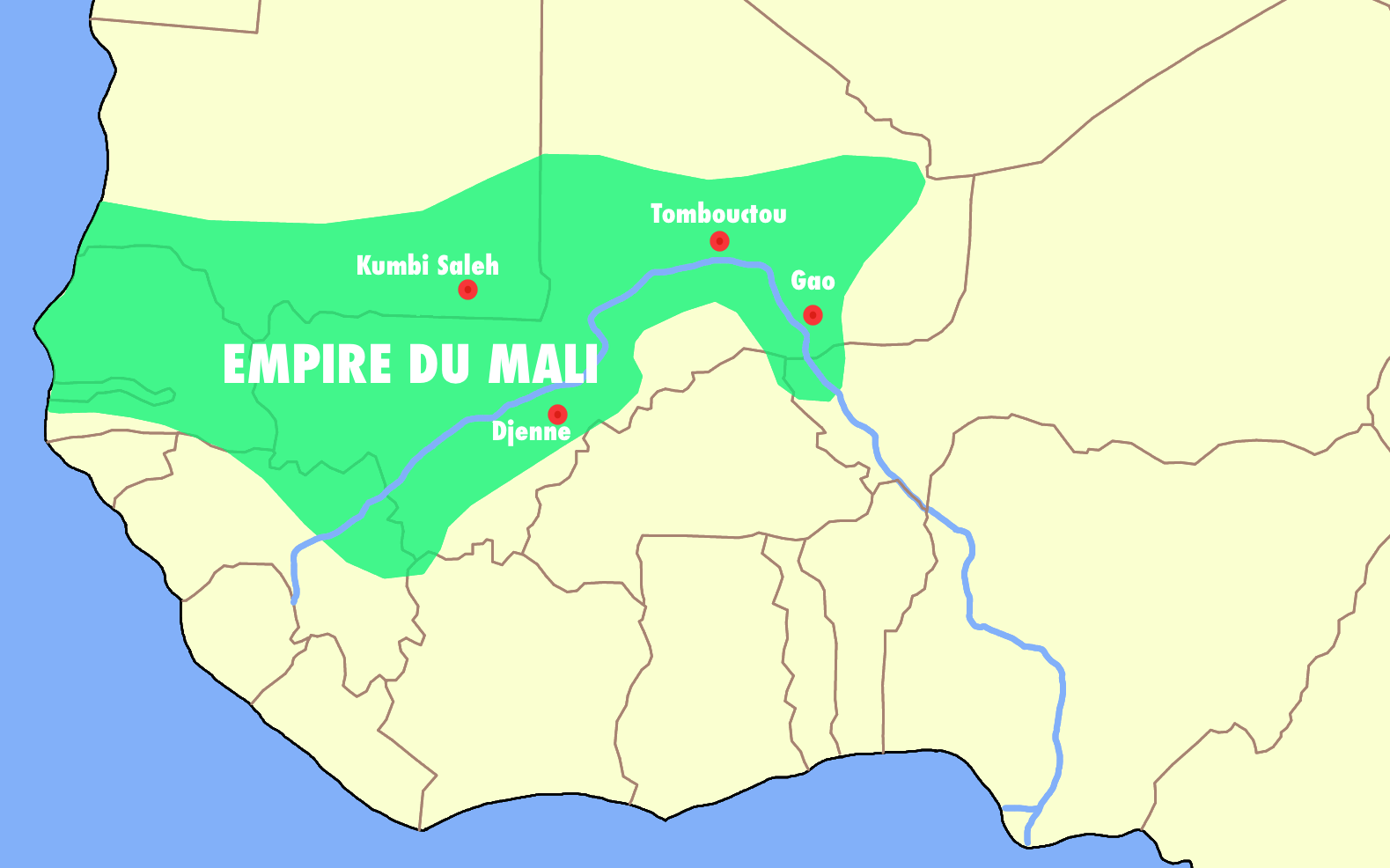

The Mali Empire, founded by the ancestors of modern Manding populations (Malinke, Bambara, Dioula, Mandinka, etc.), dominated a large part of West Africa during the Middle Ages. Stretching from Senegal in the west to Niger in the east, and from Mauritania in the north to Côte d’Ivoire in the south, this empire had its center in Mali and Guinea-Conakry. At its height in the 14th century, it covered more than one million km², becoming one of the largest and most prosperous empires in African history..

Known as Manden by Manding populations, the Mali Empire may have been called so by foreign peoples such as the Peuls. Arab writers also referred to it by various names such as Malel, Malal, Mellal, Mellit, or Mallei. The name “Mali” appears for the first time in the form “Mellal” in the 9th century.

In the 11th century, Al-Bakri¹ mentions the cities of Mellal and Daw, near gold mines, located in the region that would become the heart of the Mali Empire. In the following century, Al-Idrisi² describes Mallal as a vassal of the Ghana Empire, involved in the slave trade with the Maghreb, and mentions the neighboring great kingdom of Daw, which some researchers associate with the Soussou Empire.

The emergence of Soundjata, the Manding hero, and the birth of an empire

Around the 13th century, Soundjata Keïta, a Manding prince, led a victorious revolt against the authority of the Soussou, ruled by Emperor Soumahoro Kanté, thus seizing his territory. Soundjata’s reign was marked by the conquest of numerous territories, including that of Djoloff (present-day Senegambia), which left a positive legacy still celebrated in oral tradition.

Soundjata is also recognized for having established the Charter of Kouroukan Fouga³, considered by some as the oldest declaration of human rights, potentially abolishing slavery. However, doubts remain regarding its authenticity, as later Arab manuscripts mention the continued presence of slaves.

While Manding tradition would have favored one of Soundjata’s brothers as his successor, it was his son, Wulen, who took power. This may indicate an already present Muslim influence, especially since the famous explorer Ibn Battuta⁴ mentions that Soundjata had converted to Islam. However, Islam was only partially adopted by Mali’s rulers, some emperors deliberately refusing to Islamize their subjects—particularly those working in gold mines—in order to maximize output.

Ibn Battuta (1304–68/69) was a Moroccan Berber scholar and traveler.

After a war of succession, power was usurped by a former slave named Sakoura. His reign was marked by rich conquests, including the cities of Timbuktu, Gao, and Tekrour. Sakoura even undertook the pilgrimage to Mecca, but was assassinated by Afar warriors on his return in the Horn of Africa.

An exploration toward the Americas?

According to the account of the Arab historian Al-Umari⁵, the predecessor of the famous emperor Kankou Moussa launched a daring maritime expedition to discover what lay on the other side of the Atlantic.

During his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, Mansa Moussa told the emir of Cairo that he became king after his predecessor had equipped a fleet of 200 ships to explore the Atlantic. Only one ship returned, reporting that a mysterious river in the ocean had swallowed the rest of the fleet. Determined to find the end of the Atlantic, the king prepared 2,000 ships and personally led a second expedition, from which he never returned.

Although this account is the only known testimony of this expedition, some historians take seriously the possibility of such a voyage. Descriptions of Black men by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus have been interpreted as possible confirmation. However, no solid archaeological evidence has yet been found to support this theory.

Al-Umari’s account, reported after an interview with Mansa Moussa during his pilgrimage, provides fascinating details about this expedition. Mansa Moussa reportedly stated that his predecessor, probably Abu Bakr II, was obsessed with discovering the end of the Atlantic. After the failure of the first expedition, he himself set sail with a massive fleet, leaving the throne to Moussa.

Although intriguing, physical evidence is lacking. Archaeological research and studies of European historical documents report mentions of Black men in the Americas before Columbus, but without definitive confirmation. Some modern historians, such as Gaoussou Diawara⁶, support the idea that Malians may have reached the Americas, but this theory remains debated.

The reign of Kankou Moussa, a golden age for the Mali Empire

When the supposed predecessor, Aboubakri II, ceded the throne to Kankou Moussa, the latter became the most famous ruler of the Mali Empire. According to the Tarikh el-Fettach (Chronicle of the Scholar), a 17th-century chronicle, Moussa undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca after a tragic accident involving his mother.

His journey to Mecca has gone down in history for its incredible splendor. Moussa distributed so much gold during his travels that he caused the price of this precious metal to fall. This pilgrimage highlighted the wealth and power of the Mali Empire throughout the world.

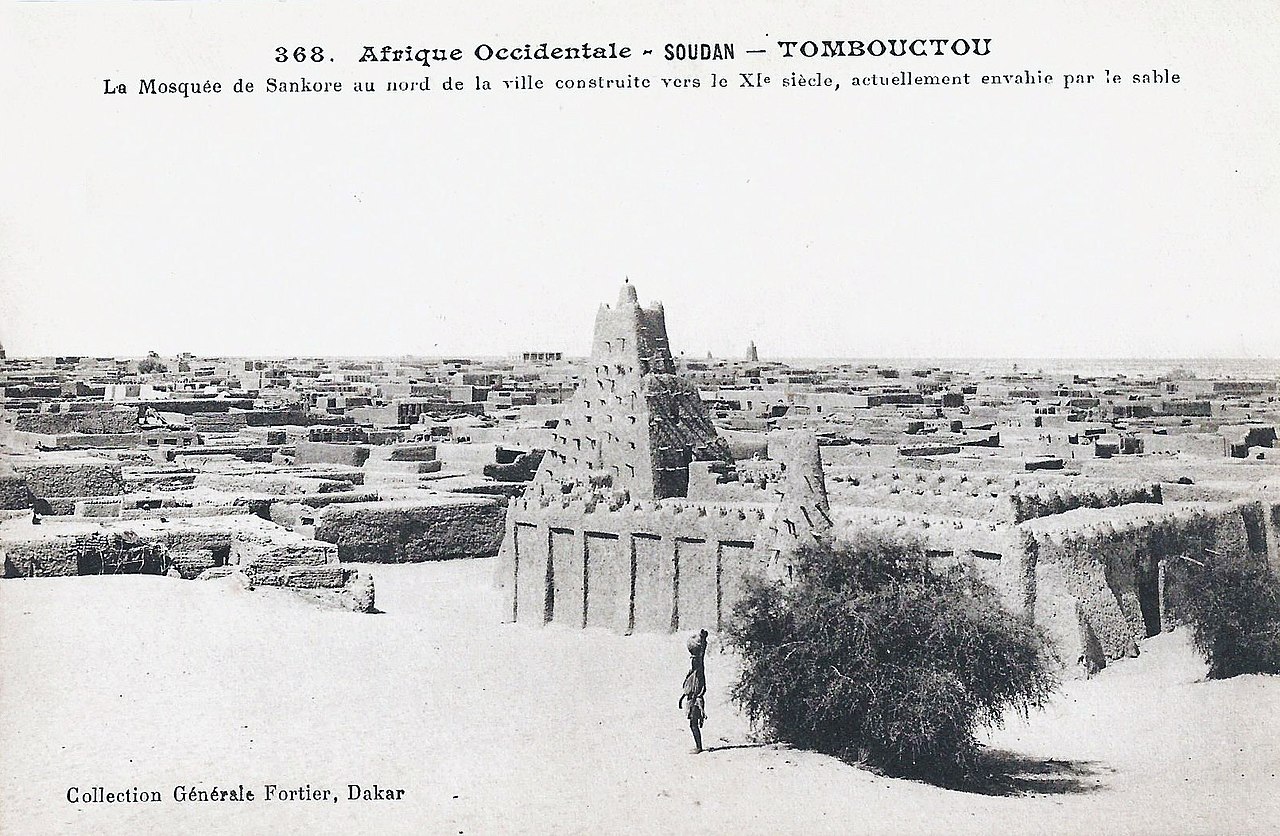

Under his reign, the empire reached its territorial peak, stretching from the Atlantic coast to the city of Essouk, from the Sahara to the southern forests. Although he did not conquer new territories through war, the extent of his influence was immense. He invited the Andalusian architect Al-Sahili⁷, who designed many buildings, including the famous Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu.

Moussa played a crucial role in promoting Islam in Mali, building mosques and centers of learning in Timbuktu. He also sent students to study in Fez, Morocco. A scholar from Mecca, Abd al Rahman al-Tamimi⁸, noted that the scholars of Timbuktu surpassed his own knowledge in Islamic law.

Moussa died in 1337 after sending an embassy to the sultan of Morocco. Although he is criticized in oral tradition for having spent the empire’s wealth, thus leading to its decline, his reign remains an emblematic period of prosperity and cultural influence for the Mali Empire.

The decline of the Mali Empire

After the death of Kankou Moussa, his son Maghan took power but suffered a defeat against the Mossi kingdom of Yatenga (present-day Burkina Faso). His brother, Souleymane, is described by Al-Umari as the most powerful Muslim Black African king. Under his reign, the empire counted 13 provinces, including the former territories of Ghana, Gao, and Tekrour, with the capital at Niani. However, excavations suggest that the former capital may have been Sorotomo, near Ségou in Mali.

At this time, the empire began to lose influence due to attacks by the Tuaregs, Peuls, and Songhai, who founded the Songhai Empire. The last emperor, Mahmoud, moved the capital from Niani to Kangaba, the seat of the Keïta royal family. After the defeat of Songhai by the Moroccans, Mahmoud attempted to retake Djenné but failed. The Mali Empire then split into several autonomous political entities, marking the end of the Keïta dynasty and of the empire.

To learn more

To deepen your knowledge of the Mali Empire and its cultural and historical influences, consult the following works:

- In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature, and Performance, edited by Ralph A. Austen

- In Quest of Susu, HA, 21 (1994), by Stephan Bühnen

- En finir avec l’identification du site de Niani (Guinée-Conakry) à la capitale du royaume du Mali, by F.-X. Fauvelle-Aymar

- The History of Islam in Africa, edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall Pouwels

- The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, edited by Peter Mitchell and Paul Lane

- L’Afrique soudanaise au Moyen Âge : Le temps des grands empires (Ghana, Mali, Songhaï), by Francis Simonis

Footnotes

- Al-Bakri: Al-Bakri (1014–1094) was an Andalusian geographer and historian. His writings, notably in Book of Roads and Kingdoms, offer valuable descriptions of West African regions, including early accounts of the Ghana Empire and the cities of the Mali Empire. ↩︎

- Al-Idrisi: Al-Idrisi (1100–1165) was an Arab-Andalusian geographer and cartographer. He is famous for his work Nuzhat al-Mushtaq, which describes many regions of the known world, including West Africa, and for his detailed maps used for centuries. ↩︎

- Kouroukan Fouga: The Charter of Kouroukan Fouga is an oral constitution attributed to Soundjata Keïta, founding the Mali Empire. Considered one of the earliest declarations of human rights, it regulated various aspects of Manding society. ↩︎

- Ibn Battuta: Ibn Battuta (1304–1369) was a Moroccan explorer and scholar. His travels took him across Africa, Asia, and Europe, and his accounts provide valuable descriptions of many cultures, including the Mali Empire. ↩︎

- Al-Umari: Al-Umari (1301–1349) was an Arab geographer and historian. His writings, based on interviews with travelers such as Mansa Moussa, provide important information on the history and culture of the Mali Empire. ↩︎

- Gaoussou Diawara: Gaoussou Diawara is a Malian historian. He is known for his research on the maritime expeditions of the Mali Empire and his theories on transatlantic explorations before the arrival of Europeans. ↩︎

- Al-Sahili: Al-Sahili (1290–1346) was an Andalusian architect invited by Kankou Moussa. He designed several emblematic buildings, including the famous Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, significantly influencing Islamic architecture in West Africa. ↩︎

- Abd al Rahman al-Tamimi: Abd al Rahman al-Tamimi (1140–1207) was a scholar from the Mecca region. During his visit to Timbuktu, he was impressed by the level of knowledge in Islamic law of local scholars, testifying to the importance of education in the Mali Empire. ↩︎