January 1811. In the winter humidity along the banks of the Mississippi, a column of several hundred armed men in rags advances toward New Orleans. They are neither looters nor desperados. They are insurgent slaves, gathered in the heart of the “German Coast,” a strategic agricultural region about fifty kilometers north of the city. Their objective is clear: strike at the heart of slaveholding power, seize their freedom by force, and make the racial order that oppresses them tremble. Their attempt will fail in blood, their memory will be buried, and their insurrection (yet the largest slave revolt in the entire history of the United States) will sink into organized oblivion.

Louisiana in 1811 is not yet a full American state. It is a territory recently purchased by the United States from France in the famous Louisiana Purchase (1803), but whose culture, elites, and social structures remain deeply marked by the French and Spanish colonial legacy. A land of white Creoles, free people of color, slaves born in Africa or the West Indies, and Haitian exiles who recently arrived after the independence of Saint-Domingue. An unstable crossroads between several worlds: republican and monarchical, Atlantic and continental, revolutionary and slaveholding.

It is this fragmented context, this moment of suspension between sovereignties, that makes an insurrection of such scale possible (and thinkable). For the revolt of January 8, 1811 does not emerge from nothing. It is part of a transatlantic dynamic, that of the Black revolutions begun in Saint-Domingue in 1791 and echoed across the Americas. Beneath the clamor of machetes and the violence of reprisals lies an idea: that slaves can become armies, and that freedom is not granted, but taken.

Nofi’s objective is to restore the complexity of this singular event. To return to its ideological origins, its organization, its methodical crushing, but also to the long silence that surrounded it. To understand why an insurrection of this magnitude left so little mark on American historical narratives, and what that says not only about the history of the United States, but about its selective memory. For the New Orleans revolt, more than a simple flare-up of servile violence, was a structured attempt at overthrow. And its erasure was a political strategy.

A revolt born from the ashes of Saint-Domingue

At the heart of the January 1811 revolt stands an opaque but central figure: Charles Deslondes. Little archival material survives about his life, but what is known is enough to grasp the symbolic intensity he carried. Born in Saint-Domingue, probably freed in his youth, he was captured or sold during the upheavals caused by the Haitian Revolution and then transferred to the sugar plantations of Louisiana. There he became one of the many Haitian exiles who had known the Black Republic before being reduced to slavery in a Southern society that ignored even their past.

Deslondes was not an ordinary slave. He held the position of commandeur (that is, a Black overseer) on the plantation of Major Manuel Andry, in LaPlace. This strategic role gave him direct access to resources, men, logistical routes, and flows of information. He was therefore not merely a leader of men through force or persuasion: he was a strategist. He knew what a well-planned insurrection represented, having seen its effects in the countryside of Saint-Domingue. He did not flee the Haitian Revolution: he carried it with him, buried, in the silence of the fields.

Around him gravitated slaves from the French West Indies (Haiti, Guadeloupe, Martinique) but also Louisiana Creoles, who had likewise grown up in an environment of intense political circulation. The idea of a collective uprising was therefore not foreign to this community. It was the direct echo of what had happened in Saint-Domingue two decades earlier: an army of slaves, structured, disciplined, capable of bending an empire. In people’s minds, Haiti was not merely a memory: it was a model.

The Louisiana authorities, moreover, were perfectly aware of this. Since 1804, repressive measures had multiplied to prevent any Haitian contagion. The presence of former free people reduced to slavery was perceived as a diffuse threat, an ideological hotspot difficult to extinguish. Newspapers of the time regularly evoked the fear of an “American Saint-Domingue,” which planters associated with the disintegration of the racial order.

But Haitian influence was not the only source of inspiration. In 1800, Gabriel Prosser had attempted to organize a massive revolt in Virginia, also based on seizing urban power. Jean Saint Malo, at the end of the eighteenth century, had gathered hundreds of fugitives in the Louisiana swamps, forming a society of free and resistant slaves. These figures were not known only to historians: they circulated orally among the enslaved, they nourished songs, rumors, and stories of hope.

The revolt of 1811, led by Deslondes and his companions, thus fits into a long historical thread: that of Black resistance in the North Atlantic. It was neither improvised nor isolated. It was the fruit of a discreet, underground, but persistent ideological transmission. An idea traveled from Saint-Domingue to the cane fields of Louisiana: that freedom is not a gift, but a right to be conquered. And that to conquer it requires leaders, tactics, and memory.

The insurrection on the plantations of the German Coast

On the morning of January 8, 1811, the revolt breaks out on the plantation of Major Manuel Andry, in LaPlace, in the heart of the region then known as the “German Coast,” named after the first European settlers who had established themselves there. It is there that Charles Deslondes and his accomplices give the signal for the insurrection. The assault is brutal and determined. The major’s son is killed, Andry himself seriously wounded. The main house is ransacked, weapons seized, supplies burned. The insurgents set out on the march.

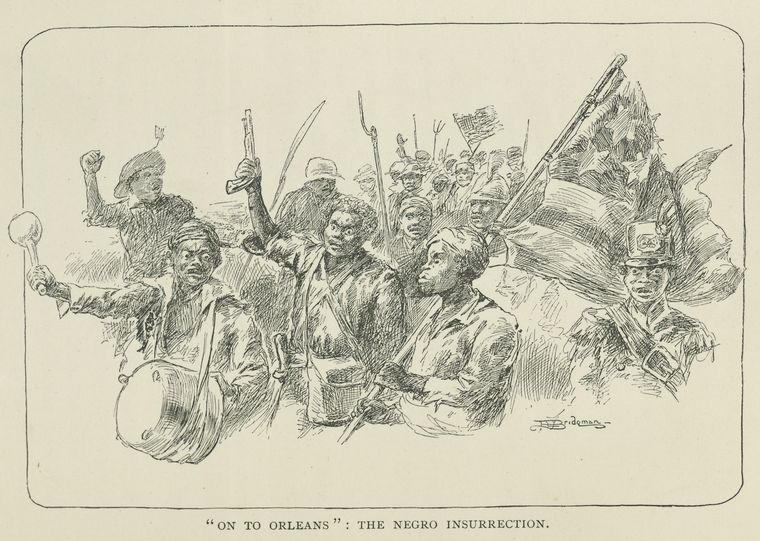

From the very first hours, the scale of the uprising is striking. According to the testimonies collected after the repression, between 400 and 500 slaves took part in the revolt. A number that makes the New Orleans insurrection the largest slave revolt in the entire history of the United States, surpassing that of Nat Turner (1831). The insurgents are not disorganized. Armed with machetes, axes, sharpened sticks, and a few seized firearms, they advance in formation. Some wear uniforms recovered from the plantations. They sing, beat drums, and call on other slaves to join them. They march with a clear direction: New Orleans.

The choice of this route is not accidental. It is not simply a matter of fleeing into the swamps or reaching a protective border. The project is political. The seizure of the city, which concentrates the military, commercial, and administrative power of the region, could have served as both a symbolic and strategic lever. In the manner of the assault on Port-au-Prince by the Haitian insurgents two decades earlier, the rebels aim for the heart of white power. They move from plantation to plantation, setting buildings on fire, destroying records, freeing those who wish to join them. Groups of mounted men serve as scouts. Lookouts warn of possible roadblocks.

The slaveholding order, brutally taken by surprise, wavers for several hours. Panic spreads among planter families. Militias are mobilized in emergency. In New Orleans, Governor William Claiborne and General Wade Hampton order the formation of an expeditionary force to block the advance. But time is short: at several kilometers per hour, the insurgents could reach the city within two days. What is being played out is a battle at a distance between two logics of organization: on one side, a suddenly vulnerable white power; on the other, an army of slaves determined to overturn history.

The revolt does not limit itself to acts of revenge. It traces an axis, a strategy, a geography of reconquest. For the first time on American territory, slaves collectively attempt to take an entire city in order to found an alternative there. They do not hide. They make themselves seen. Their advance, punctuated by fire and cries, is a declaration of war. A war waged against a world structured by enslavement, but one that had never imagined it could waver. For two days, that world truly does waver.

Betrayal, encirclement, and military repression

On January 9, barely twenty-four hours after the uprising began, a brutal reversal shifts the balance of power. One of the enslaved men involved in the insurrectionary march, for unknown reasons (fear, pressure, opportunism), deserts the rebels’ ranks and surrenders to local authorities. His testimony proves decisive. It reveals the size of the column, its progress, its probable destination, and the names of several leaders. Thanks to this information, Governor Claiborne and Generals Hampton and Cushing can organize a rapid counterattack.

The reaction matches the level of panic: swift, massive, and without nuance. The territorial militia is hastily mobilized, supported by federal troops, as well as armed planters themselves. This is not merely a military operation; it is a social crusade. The prospect of seeing New Orleans fall into the hands of revolting slaves is deemed inconceivable. The objective is not dispersion; it is annihilation.

The confrontation takes place on January 10, near Kenner, along the banks of the Mississippi. Poorly equipped against armed and trained men, the insurgents are crushed. The fight quickly turns into a massacre. Contemporary accounts report at least 66 slaves killed, some in the melee, others shot while fleeing. Several dozen are captured, wounded or not, and transported to the region’s plantations, where improvised “courts” are convened in the following days.

The repression exceeds even the judicial standards of the time. At the Estrehan plantation, a war council (composed of local notables, all slave owners) summarily judges the prisoners. In a single day, 16 death sentences are pronounced. The executions are public, immediate, and spectacular. Bodies are mutilated, heads severed, impaled, and displayed at regular intervals along the road between the German Coast and New Orleans. Each head on a spike serves as a warning to those who might dare dream of emancipation. The example is meant to strike, freeze, and terrorize.

Deslondes himself, captured alive, suffers an especially cruel fate. His hands are amputated, he is tortured, executed, and then burned on the spot. This treatment aims to turn his body into a counter-myth: to annihilate any form of heroization. He is not to die as a war chief, but as a criminal punished. The message is clear: the slaveholding order tolerates no armed insubordination. It treats it like a leprosy to be eradicated, through fire and example.

The violence of the repression is not explained solely by fear. It is also due to the scale of what the insurgents dared to envision: taking a city, challenging the army, forcibly abolishing an entire economic system. For this, they must be erased—physically, symbolically, historically. And that is precisely what the American colonial apparatus sets out to do in the following days. The purge is both military and memorial.

The revolt confronted by the law (judgment, spectacle, and punishment)

The January 1811 revolt was not only crushed militarily. It was also crushed within a judicial theater, where the law, far from being a safeguard, served as an extension of social vengeance. The judgments rendered in the days following the clashes meet none of the criteria of a fair trial. The war councils (such as the one convened at the Estrehan plantation) were composed exclusively of planters, i.e., slave owners directly involved, both victims, judges, and executioners.

No defense was allowed. No contradictory investigation was conducted. The accused had no lawyer, no voice in the proceedings, and were judged in haste. The goal was not to administer justice but to produce an example. In this framework, law is instrumentalized: it becomes theater. Each sentence is a staged performance; each execution, a political choreography.

The torment goes far beyond physical elimination. It aims to reconstruct the symbolic order threatened by the insurrection. The heads displayed on spikes along the Mississippi, between the German Coast and New Orleans, are not merely warnings: they are proclamations of authority. Space is reshaped by fear; roads become corridors of visual domination, where each stake, each skull, recalls white sovereignty.

It is no coincidence that Charles Deslondes suffers an even crueller fate. While others are shot, he is amputated, tortured, then burned. This differentiated treatment reveals a clear intention: to erase the very possibility of a Black heroic figure. The leader must not die as a war chief but as a disarticulated monster. The punishment is political: it aims to disqualify all memory, to make impossible the transformation of the punished into a martyr.

The legal consequences of this repression are swift. In the following months, Louisiana authorities significantly reinforce their control arsenal: drastic limitations on the movement of slaves, prohibition of gatherings, enhanced militia patrols, and increased surveillance of Haitian free people. The Louisiana Black Code, already inspired by French texts but adapted to American conditions, is hardened. Any attempt at assembly or collective dissent is equated with armed rebellion.

This reaction reflects enduring fear. Masters had not merely seen their authority challenged; for two days, they had witnessed the possibility of a total overturning of the social order. Legal repression, far from restoring balance, inscribes the dominants’ anxiety into law. By striking without nuance, denying the right to defense, the American slave system reveals its vulnerability. Its strength is rooted only in terror. And in 1811, this terror takes the form of law without justice, punishment without mercy, verdict without memory.

A forgotten insurrection or one deliberately concealed?

For nearly two centuries, the 1811 revolt was kept in near-historical silence. Neither mentioned in American textbooks nor commemorated nationally or regionally, it vanished from official narratives. It was only at the turn of the 21st century that historians, activists, and cultural institutions began to unearth this buried memory. But why did an insurrection of such scale (the largest in United States history) remain so marginal in collective consciousness?

The explanation lies first in the construction of a dominant white memory in the American South. From the end of the Civil War, the Confederate imagination imposed itself as the foundational narrative in Louisiana: celebration of plantations, rehabilitation of Southern figures, victimization of white owners. In this narrative, there was no room for insurgent slaves, let alone for an organized Black army seeking to take New Orleans. Such a memory would have forced a questioning not only of the injustice of slavery but of the very legitimacy of the social order supporting it.

By contrast, figures like Nat Turner, who led an insurrection in Virginia in 1831, managed to embed themselves in American history despite controversies. Turner benefited from greater documentation, contemporary narratives spread in the abolitionist North, and militant reinterpretation in the 1960s. But Charles Deslondes remains a faceless figure. No photograph, no diary, no published account during his lifetime. His tortured body left few traces. And his act was interpreted less as resistance than as a neutralized threat.

The concealment is therefore deliberate, structured, and methodical. Erasing the 1811 revolt allowed neutralizing its political potential, cutting off any connection to Haiti, and locking in the idea that Black liberation could not emerge on U.S. soil. Oblivion was a strategy of continuity. And this forgetting lodged itself everywhere: in incomplete archives, in the absence of monuments, in narratives glorifying militias and planters.

It is only in the 21st century that an unprecedented memory work begins to emerge. In 2014, the Whitney Plantation, turned into a slavery museum in Louisiana, dedicates a space to the 1811 revolt. In 2019, artist Dread Scott organizes a full-scale reenactment of the insurgents’ march, gathering several hundred participants in costume, chanting Creole slogans, marching toward New Orleans. This artistic, performative, and historical act restores to the insurrection its body, breath, and memory. It reminds us that this history was not a marginal accident, but a potential tipping point.

Through Deslondes and his companions, another America emerges: an America in which slaves do not wait for abolition, but take up arms. An America where the Black Republic born in Saint-Domingue could have found an echo in the Southern bayous. And finally, an America in which Black memory no longer accepts being merely a victim, but claims a full and central place in the national narrative.

Revolt or Black war? A strategic rereading of the event

Long labeled a “slave rebellion,” the January 1811 insurrection today deserves a strategic, lucid rereading, free of paternalism or romanticism. For the facts are clear: the insurgents did not flee. They did not vandalize blindly. They did not act in panic. They marched in formation toward a defined objective. What they undertook was an attempt to seize power. Not a riot. A military operation.

The available sources (though fragmentary) reveal logistical organization, an informal hierarchy, a reasoned use of violence, and structured geographic progression. All of this evokes less a spontaneous revolt than an attempt at asymmetric warfare, conceived with available means. The weaponry (machetes, axes, cutting tools), the numbers (over 400 men), the direction (New Orleans), the chosen timing (early in the year, while production lay dormant): every element testifies to tactical intelligence.

It was not about individual liberation or fleeing north. The project carried by Deslondes and his companions was collective and territorial: to seize an urban center, overthrow local slaveholding power, and (perhaps) proclaim a new order. Some historians entertain the hypothesis of a second Haiti: a Black republic, born in the very heart of American territory, modeled after the state founded by Dessalines and Christophe. This hypothesis, though unprovable, aligns with the profile of the leaders, some former free or freed Haitians, trained in a context where Black insurrection was not only possible, but victorious.

Rethinking 1811 as an attempt at Black secession (not legal, but military) radically changes the interpretation of the event. We no longer speak of slaves rising, but of an insurgent body declaring war on an established order. This perspective aligns with contemporary theories of asymmetric warfare, where a minority, poorly armed group challenges a superior power by exploiting internal weaknesses: surprise, dispersion, refusal to acknowledge the threat.

In this sense, the New Orleans insurrection transcends its local context. It becomes a key milestone in an Atlantic history of Black resistance, where Saint-Domingue, Jamaica (with Sam Sharpe’s 1831 war), Barbados, or Suriname are other crystallization points. What these movements share is the articulation between military action and political ambition.

In New Orleans, in January 1811, a Black army rose with a plan, a trajectory, and a project. What history long presented as a servile revolt was, in reality, an organized insurrection attempt. And if it failed, it was less due to disorganization than to brutal suppression. It was not the dream that was lacking: it was time.

New Orleans 1811: Foundational fracture of a racial America

The New Orleans revolt of January 1811 was not a simple servile twitch, much less a regional anomaly. It was a fracture. A moment when the racial order structuring young America showed its flaws, brutality, and vulnerability. The rapid reaction, methodical extermination of insurgents, and macabre staging of the repression are not the result of a one-time excess. On the contrary, they inaugurate the consolidation of a hardened racial regime, where any Black dissent becomes an existential threat to the slaveholding state. It is no coincidence that, after 1811, Louisiana experienced a spectacular hardening of its legislation, reinforcement of militias, and militarization of control over Black populations, free or enslaved.

The carefully maintained forgetting around this insurrection is not negligence. It is a political act. For this event clashes with the founding narrative of an America built on liberty, emancipation, and democracy. It reminds us that this liberty was founded on the oppression of millions of captives, and that they were not passive. They fought. They tried to overthrow power. And America, far from integrating them into its heroic memory, relegated them to the margins, the ditches of history, the silences of archives.

Reintegrating the 1811 revolt into history does not mean rehabilitating martyrs. It means understanding that Black struggles for sovereignty were not confined to Haiti or Africa. They took place here, on U.S. soil, in the first decades of the republic. They spoke French, Creole, English. They wielded machetes and revolutionary slogans. They attempted to create another history; an American history, but Black.

Through Deslondes and his companions, a whole repressed chapter of national memory resurfaces. Their insurrection is not a forgotten fragment: it is a branching point. A moment when the South could have tipped differently. An alternative stifled in blood, but never completely erased.

Returning to this revolt, analyzing it in all its political and strategic scope, is to question the foundations of American memory. Not to impose a victim narrative, but to restore a historical truth: that of men and women who, in the cane fields, dreamed of statehood, dignity, and overthrow. And in doing so, laid the first stones (still invisible) of Black sovereignty on American soil.

Contents

- A revolt born from the ashes of Saint-Domingue

- The insurrection on the plantations of the German Coast

- Betrayal, encirclement, and military repression

- The revolt confronted by the law (judgment, spectacle, and punishment)

- A forgotten insurrection or one deliberately concealed?

- Revolt or Black war? A strategic rereading of the event