In 1834, a few hundred African Americans landed at Cape Palmas, on the western coast of Africa. Their ambition was immense: to found a free society, far from the racism and humiliations endured in the United States. Twenty-three years later, their Republic vanished, absorbed by neighboring Liberia. The episode was brief, nearly erased from textbooks, yet it concentrated all the contradictions of the nineteenth-century Atlantic world: ambiguous abolitionism, colonization under a philanthropic banner, proclaimed sovereignty without real social grounding, and a lasting fracture between diasporic elites and Indigenous populations.

The Republic of Maryland (sometimes called Maryland-in-Africa) was less a state than a political projection. It was born of an American anxiety, rooted itself in a utopia of return, and collapsed under the weight of an African reality it had neither understood nor integrated.

Maryland-in-Africa: the illusion of return or the birth of a state without a nation?

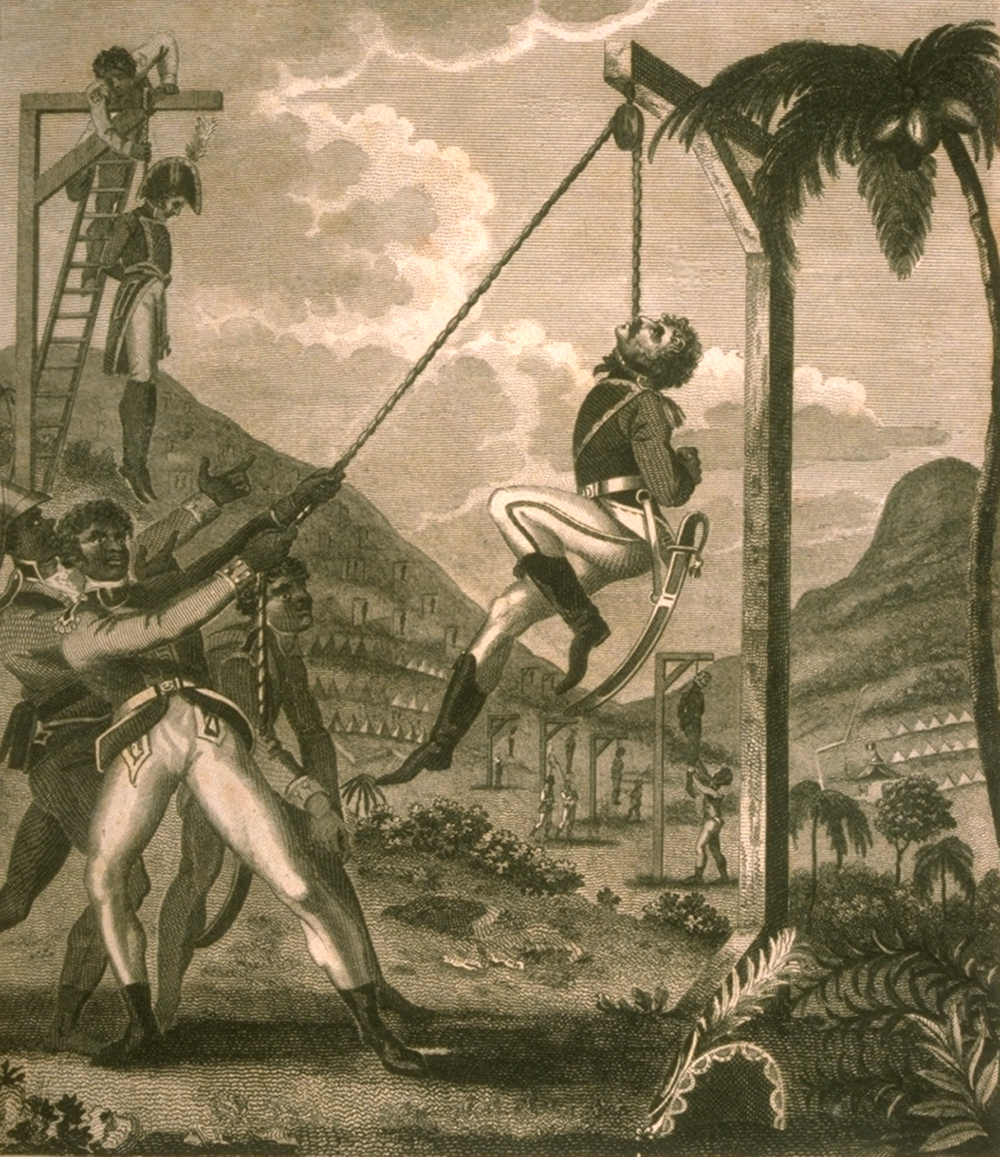

The haitian shockwave

To understand the birth of Maryland-in-Africa, one must return to 1804. The independence of Haiti was not merely a rupture in colonial history; it acted as an ideological earthquake in the United States. For the first time, a slave revolution triumphed and founded a sovereign Black state. The event fueled hope among the oppressed and panic within slaveholding societies.

In the Southern states, fear of a general uprising spread. In the Northern states, where abolition was advancing, another concern emerged: what should be done with freed people? Full civil equality remained unacceptable to a large segment of public opinion. Structural racism ran through moderate abolitionists and slaveholders alike. One idea then imposed itself as a compromise: organizing the departure of free Blacks to Africa.

In 1816, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded. The organization brought together ideologically opposed profiles: humanitarians convinced they were offering African Americans a better future, and slaveholders eager to remove a free population perceived as subversive. The official objective was generous (“return” to Africa), but the implicit logic was political: to stabilize the American racial order.

The term “repatriation” was misleading. The majority of candidates for departure were born in the United States; their ancestors had been deported sometimes two centuries earlier. Africa was not a lived homeland, but a moral abstraction, an idealized land where history might begin anew.

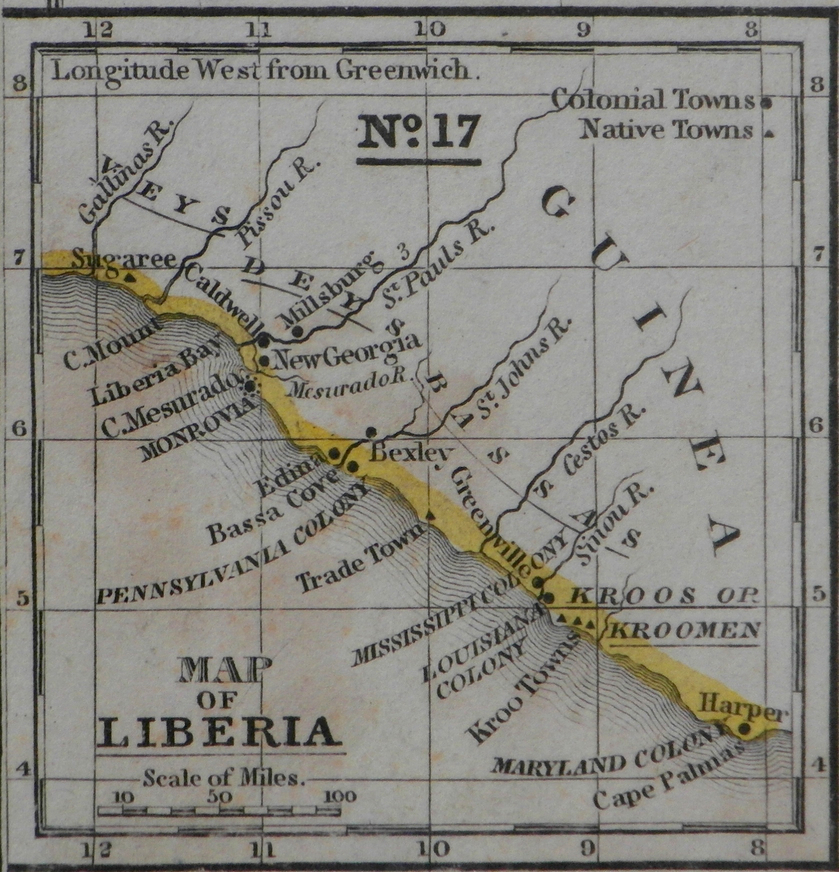

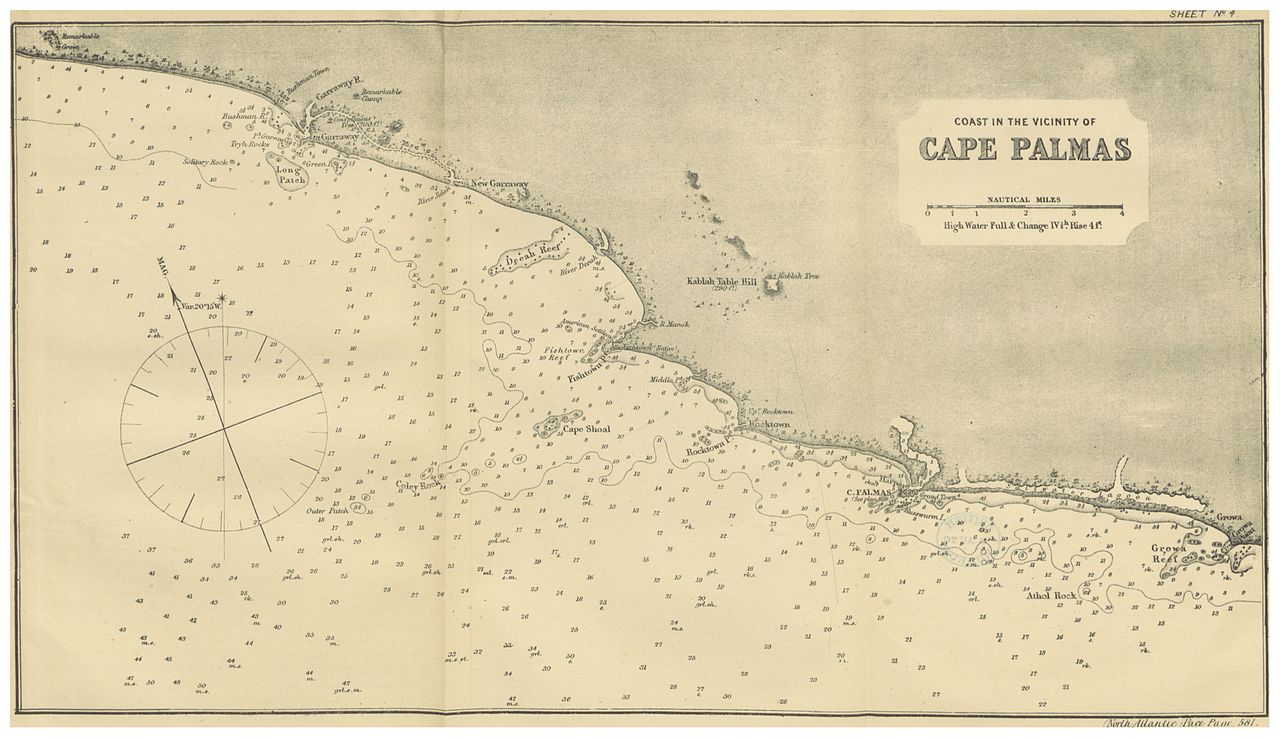

Within this context, the Maryland State Colonization Society, an autonomous branch linked to the state of Maryland, decided to create its own settlement. In 1834, an expedition established a colony at Cape Palmas, southeast of the nascent Liberian territory.

The choice of site was not insignificant. Cape Palmas occupied a strategic position on the coast, near territories inhabited by the Grebo and Kru peoples. The location allowed control of coastal trade and opened potential access to the interior.

The institutions established reproduced those of the United States: a governor, an assembly, legal codes inspired by American law. The colony conceived of itself as a cultural and political extension of America, transplanted to Africa. The official language was English, and the dominant religion Protestantism.

Yet this transplantation confronted a fundamental reality: the land was not empty. Local societies possessed political structures, commercial networks, and territorial traditions. Maryland’s installation rested on unequal treaties, often poorly understood, establishing a fragile coexistence.

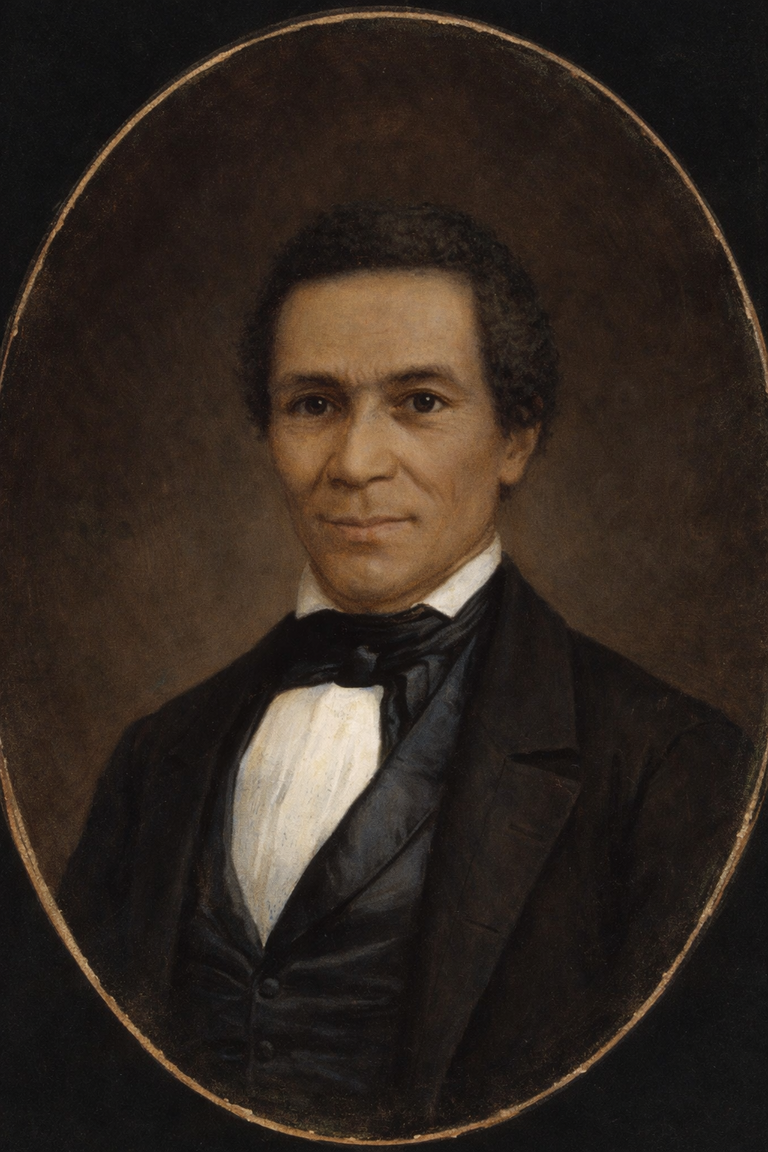

John Brown Russwurm: the ambiguity of a diasporic leadership

At the head of the colony stood John Brown Russwurm, an African American intellectual, journalist, and activist. He embodied the paradox of the project: trained in American abolitionist debate, he ultimately defended colonization as a pragmatic solution.

Russwurm believed in the possibility of an autonomous Black state in Africa. But he had to contend with a structural weakness: the colony remained financially and logistically dependent on the United States. Resources were limited, arrivals of settlers irregular, and the population too small to ensure effective defense.

His political authority rested more on moral legitimacy than on real power. He governed a diasporic minority amid numerically dominant Indigenous populations.

1854: the proclamation of a fragile sovereignty

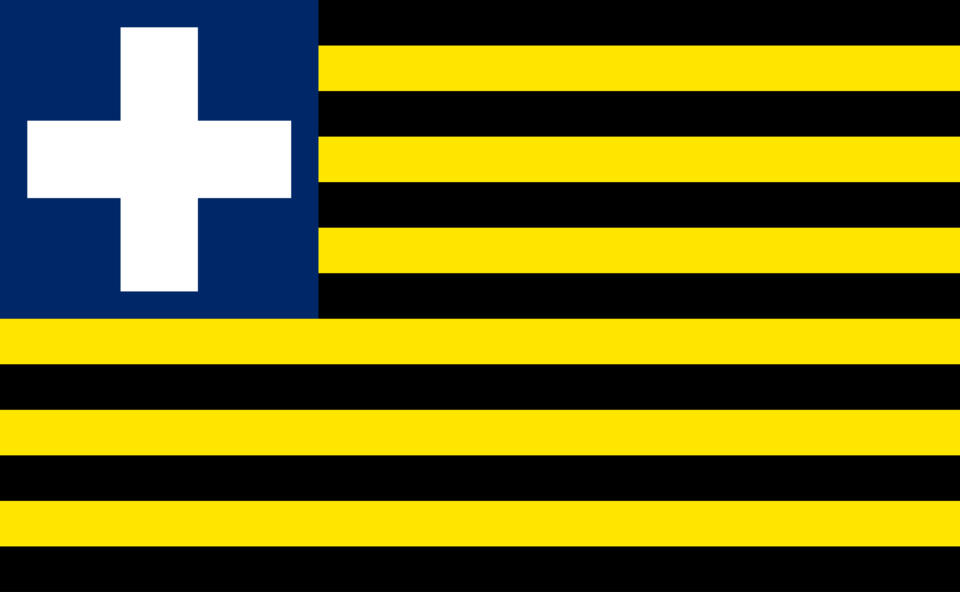

On May 29, 1854, Maryland proclaimed its independence. The act was solemn. The young Republic adopted its national symbols and affirmed its will to exist as a sovereign state.

But sovereignty was primarily juridical. The population barely exceeded a few thousand. The economy relied on coastal trade and the export of agricultural products. The army was embryonic.

More seriously still, the Republic lacked a unified nation. The African American settlers formed a distinct elite, culturally and socially separate from the Grebo and the Kru. They often perceived themselves as bearers of a civilizing mission, paradoxically reproducing the hierarchies they had endured in the United States.

Maryland thus became a state without a nation: an institutional construction without deep social integration.

Tensions with local populations soon intensified. The Grebo in particular challenged the Republic’s territorial expansion. Commercial and land disputes degenerated into armed clashes.

War broke out in 1856. Maryland, incapable of sustaining a prolonged conflict, requested assistance from Liberia. This military dependence sealed its fate.

The episode revealed a fundamental error of the Afro-American colonial project: underestimating the political and demographic complexity of African societies. The settlers had imported a state model without building local legitimacy.

1857: annexation and the end of the illusion

In 1857, Maryland accepted its annexation by Liberia. Its independence had lasted only three years.

Liberia itself, founded by the American Colonization Society, rested on a similar structure: political domination by Americo-Liberians over Indigenous populations. Maryland’s merger into Liberia did not resolve the fracture; it integrated it into a broader framework.

The Maryland experiment disappeared as a sovereign entity, yet it left a lasting imprint on Liberian political history.

Maryland’s economy depended primarily on maritime trade. It failed to structure an integrated hinterland.

The absence of regional integration rendered the state vulnerable. Revenues were insufficient to finance a robust administration or credible defense. The Republic lived in a trading-post economy, exposed to Atlantic fluctuations.

The Republic of Maryland raises a delicate question: was the project an attempt at liberation or a form of inverted colonization?

The African American settlers, themselves victims of American racism, adopted in Africa attitudes of cultural superiority. The civilizing mission, Christianization, and political centralization reflected a logic of elite implantation.

The project did not lead to cultural fusion. It established a lasting dualism.

The history of Maryland in Africa is not a mere colonial anecdote. It constitutes a laboratory of diasporic contradictions.

It challenges the myth of “return.” Can a nation be rebuilt on the basis of a fragmented memory? Can an institutional model be transplanted without social rootedness?

Maryland failed because it confused sovereignty with implantation, legitimacy with proclamation, and memory with territory.

Utopia and reality…

The Republic of Maryland was a bold attempt, driven by hope and undermined by its ambiguities. It reveals the complexity of the nineteenth-century Black Atlantic: aspirations to autonomy, the weight of American racial structures, and the difficulty of articulating diaspora and African societies.

Its brief existence recalls a timeless political truth: a state is not born from a declaration, but from territorial and social consensus. Maryland had a Constitution; it did not have a nation.

And it was in this gap that its disappearance was decided.

Notes and references

Burin, Eric. Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005.

Clegg, Claude A. III. The Price of Liberty: African Americans and the Making of Liberia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Shick, Tom W. Behold the Promised Land: A History of Afro-American Settler Society in Nineteenth-Century Liberia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Akpan, M. B. “Black Imperialism: Americo-Liberian Rule over the African Peoples of Liberia, 1841–1964.” Canadian Journal of African Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 1973, pp. 217–236.

Liebenow, J. Gus. Liberia: The Evolution of Privilege. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969.

Huberich, Charles Henry. The Political and Legislative History of Liberia. New York: Central Book Company, 1947.

American Colonization Society. Annual Reports of the American Colonization Society. Washington, D.C., 1818–1860.

Russwurm, John Brown. The Liberian Herald (archives, 1830s–1840s).

Table of Contents

Maryland-in-Africa: The Illusion of Return or the Birth of a State Without a Nation?

The Haitian Shockwave

John Brown Russwurm: The Ambiguity of a Diasporic Leadership

1854: The Proclamation of a Fragile Sovereignty

1857: Annexation and the End of the Illusion

Utopia and Reality…

Notes and References