For more than thirty years, Mobutu Sese Seko transformed the Congo into a person-state, a blend of authoritarianism, personality cult, and clientelism. From Zairianization to Gbadolite, the “Versailles of the jungle,” his reign illustrates both the promises and the excesses of postcolonial Africa—caught between ostentatious splendor and silent collapse.

This dossier plunges into the heart of the “Mobutu system,” retracing the trajectory of a man who rose from the Force Publique and journalism to erect a person-state. Between the Cold War and regional struggles (Katanga, Shaba, Angola), Mobutu built a power machine grounded in symbolic engineering (Zairianization, abacost, the MPR party-state) and a methodical use of the personality cult.

The aim is to show how Zaire became at once a global strategic pivot and a factory of national illusion—until the brutal collapse of 1996–1997.

The narrative opens and closes in Gbadolite, the “Versailles of the jungle,” a symbolic place of a reign in which the staging of power masked a country in deep crisis.

Gbadolite, capital of a tropical dream

The red road slices through the equatorial forest. As one advances, banana trees part to reveal a setting that seems out of time: a monumental gate, a runway carved out of the bush, concrete frescoes shimmering with tropical humidity. Welcome to Gbadolite, the birthplace of Mobutu Sese Seko, transformed into a secondary capital and a showcase of limitless power.

At the end of the 1970s, Concorde jets from Paris landed here. Here lay the Kamanyola, a presidential yacht built like a floating palace. Here paraded heads of state, businessmen, and courtiers, invited to banquets where protocol mattered as much as the dishes. For its inhabitants, Gbadolite was no longer a village: it was a stage, a spectacle of power.

Witnesses still recall the striking contrast: a Versailles in the middle of the jungle, where electricity flowed freely while major Zairian cities sank into rolling blackouts; where gardens designed by European architects coexisted with surrounding rural poverty. Today, the palace ruins and wild grasses invading the paths tell the story of a dream eroded into a mirage.

At Gbadolite, everything was symbolic. The gate was not merely an entrance; it was the threshold of a kingdom. The presidential aircraft was not just transport; it embodied the idea of a supersonic leader—faster than his opponents, more powerful than his neighbors. The yacht was not just a vessel; it expressed the will to be pharaoh and emperor at once.

From the outset, Gbadolite reveals the key to the regime: power as total staging. More than a territory to govern, Mobutu made Zaire a stage on which he played his own role—even if the backstage (economic misery, regional tensions, state erosion) collapsed out of sight.

Youth, Training, and Early Networks (1930–1960)

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu was born on October 14, 1930, in Lisala, a small town in Équateur Province on the left bank of the Congo River. The son of a Force Publique cook who died prematurely, he grew up in an environment shaped by the rigor of Catholic missions. The White Fathers introduced him to school discipline, the French language, and respect for hierarchy—values he would internalize early.

At nineteen, he enlisted in the Force Publique, the colonial army composed of Congolese soldiers commanded by Belgian officers. There he distinguished himself by intelligence, self-assurance, and a sense of authority. The military experience left a lasting imprint on his vision of power: vertical obedience, rewarded loyalty, and codified violence as a tool of discipline.

Demobilized in 1956, Mobutu chose journalism. He joined L’Avenir, a Léopoldville daily, where he learned the arts of rhetoric and persuasion. This stint in the press proved crucial: he learned to wield words as weapons, to seduce crowds, to construct narratives. He already grasped that controlling information meant anticipating power.

On the eve of independence, Mobutu joined Patrice Lumumba’s Mouvement National Congolais (MNC). Though merely a secretary, he stood out for pragmatism and discretion. Where other Congolese leaders expressed ideological visions, Mobutu focused on networks, contacts, and the ability to navigate rival actors.

Amid the decolonization whirlwind, Mobutu attracted the attention of Larry Devlin, CIA station chief in Léopoldville. Americans were seeking a reliable profile capable of stabilizing the Congo against the Soviet specter. A trained officer, a deft journalist, a tempered nationalist—Mobutu fit the bill. This connection inaugurated a relationship that would weigh heavily from 1960 onward, during the Congolese crisis.

The young Mobutu’s trajectory followed the circulation axes of the Belgian Congo:

- Lisala, birthplace at the heart of the river.

- Léopoldville (Kinshasa), colonial metropolis where he forged social ascent.

- Brussels, an initiatory stop during training trips, a showcase of colonial power and first opening to European diplomacy.

Congolese Crisis and the Emergence of the “Key Man” (1960–1965)

On June 30, 1960, the Belgian Congo gained independence. But behind the pomp of Léopoldville, the newborn state immediately wavered. Vast and rich in strategic minerals (copper, cobalt, uranium), the country became an object of desire. Provinces (Katanga, South Kasai, Équateur) sought autonomy; parties fought among themselves; the army mutinied as early as July. The Congo became the mirror of a continent both liberated and vulnerable.

Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba sought to embody a sovereign, radical nationalism. But his combative tone, appeal to the UN, and rapprochement with Moscow exposed him. In September 1960, he was arrested, placed under house arrest, then transferred to Katanga, where he was executed in January 1961. His tragic fate made him a global icon, but his absence opened a gaping void at the top of the state.

A young colonel, Mobutu then played a decisive role. Drawing on ties to the army and to the Americans, he imposed order through a bold maneuver: the creation of the College of Commissioners-General (September 1960), an interim government composed mainly of technicians and students. This provisional solution marginalized both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu while securing Mobutu a central place in the Congolese equation.

Between 1960 and 1963, the Congo went up in flames.

- Katanga, led by Moïse Tshombe, proclaimed secession with backing from mining companies and Belgian advisers.

- South Kasai followed, in a logic of regional autonomy.

- The nascent national army conducted often bloody operations against rebellions.

- The UN deployed its largest peacekeeping mission to date, revealing the Congo as a Cold War laboratory.

Congolese destiny was not decided solely in Léopoldville; it unfolded on a planetary stage:

- Washington viewed the Congo as a strategic lock against the USSR.

- Moscow backed certain radical nationalists.

- Brussels and Paris sought to retain control over mineral resources.

- The UN, torn, became arbiter and sometimes direct actor.

In five years, the officer-turned-mediator imposed himself as the “key man”: neither ideologue like Lumumba nor institutional figure like Kasa-Vubu, but a pivot between the army, provinces, and foreign patrons. Pragmatic and discreet, he prepared to cross a threshold—the direct appropriation of power.

November 24, 1965: Seizure of Power and “Stabilization”

At dawn on November 24, 1965, the Congo tipped. After five years of protracted crisis—ephemeral governments, secessions, rebellions, foreign intrigues—President Kasa-Vubu and Prime Minister Moïse Tshombe neutralized each other. In the chaos, General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, already hailed as the “man of order” in 1960, moved first. His coup unfolded with little bloodshed: the army occupied strategic points in Léopoldville, institutions were dissolved, and Mobutu proclaimed himself head of state.

Cold War pressures loomed large. Washington, worried by left-backed rebellions and Moscow’s influence, saw Mobutu as a guarantor of stability. Brussels and Paris, anxious to protect mining interests, considered him the lesser evil. With tacit Western assent, Mobutu inaugurated his reign.

He quickly understood that fragile power asserts itself through force. In June 1966, he staged the public execution of four former ministers accused of plotting. Broadcast on radio and etched into popular memory, the scene marked an end of an era. Violence became the regime’s inaugural language.

Pierre Mulele, a former Lumumbist minister turned rebel, was lured back to Kinshasa in 1968 under promise of amnesty; he was tortured, executed, and his body displayed—a warning to all opposition. Moïse Tshombe, recalled from exile, was kidnapped in Spain in 1967 in a murky affair; his definitive disappearance removed the Katanga strongman. Joseph Kasa-Vubu was discredited and marginalized until his death in 1969.

Mobutu’s strategy was clear: eliminate alternatives, centralize power around the army, and impose his image as restorer of unity. Externally he reassured Western partners; internally he imposed silence through repression and propaganda.

Manufacturing a symbolic nation: zairianizing to govern (1971–1997)1997)

In October 1971, Mobutu crossed a threshold. The Congo ceased to exist; it became Zaire, after the local name for the Congo River (nzadi). The currency took the same name, and Léopoldville became Kinshasa. More than administrative tinkering, this was identity rewriting. By renaming places and symbols inherited from colonization, Mobutu posed as founding father of a new nation purged of foreign marks.

The sartorial symbol of this cultural revolution was the abacost (“down with the suit”). The Western tie was banned as a sign of colonial alienation. Executives and civil servants were to wear this sober Mao-collar jacket, meant to embody African authenticity and modern authority. Clothing became a sign of allegiance, disciplining bodies across streets and administrations.

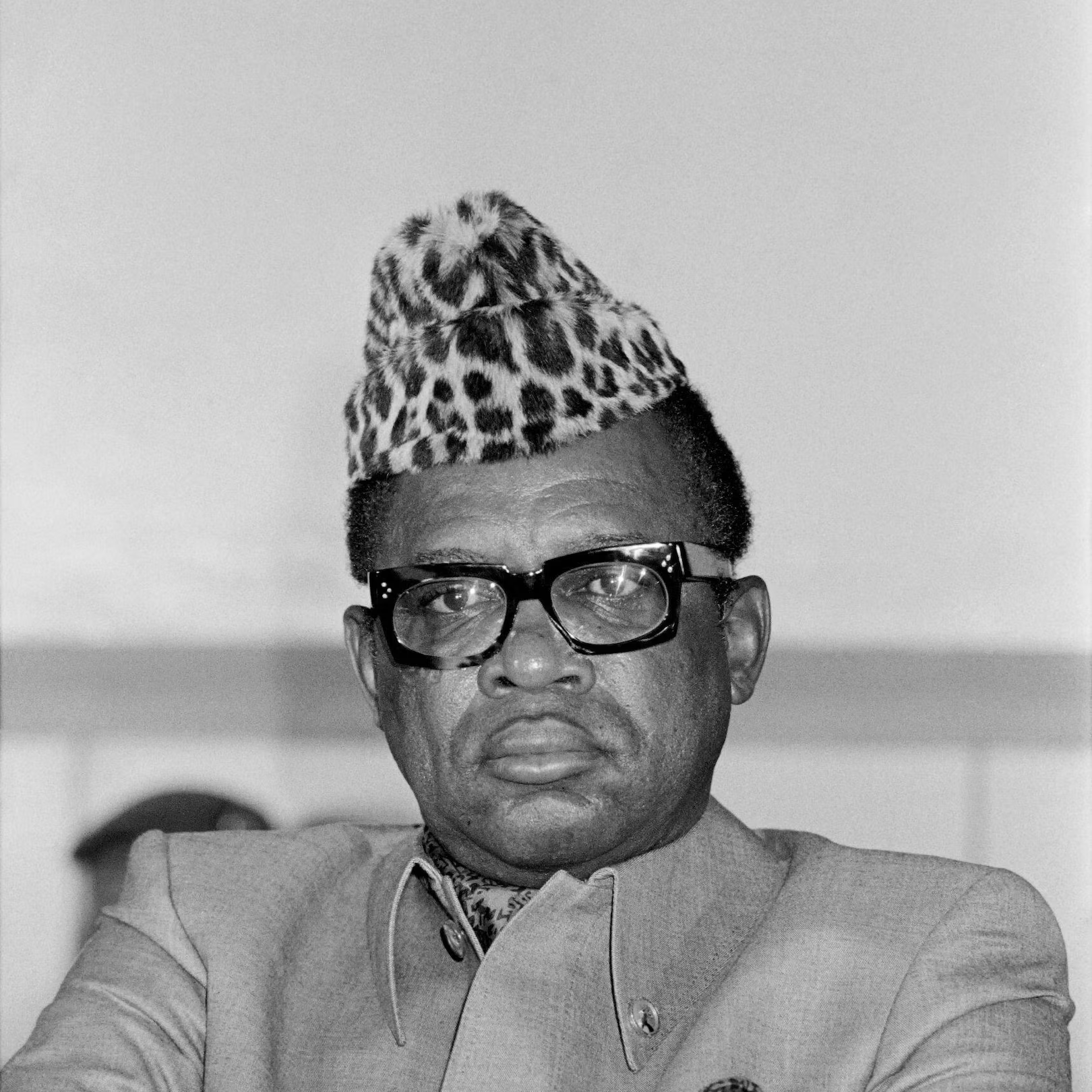

In the same vein, Mobutu imposed the abandonment of colonial Christian first names. He himself shed Joseph-Désiré to become Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga—“the all-powerful warrior who goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake.” Congolese were to follow suit, reinventing “authentic” identities. For some, liberating; for others, an arbitrary intrusion into private life.

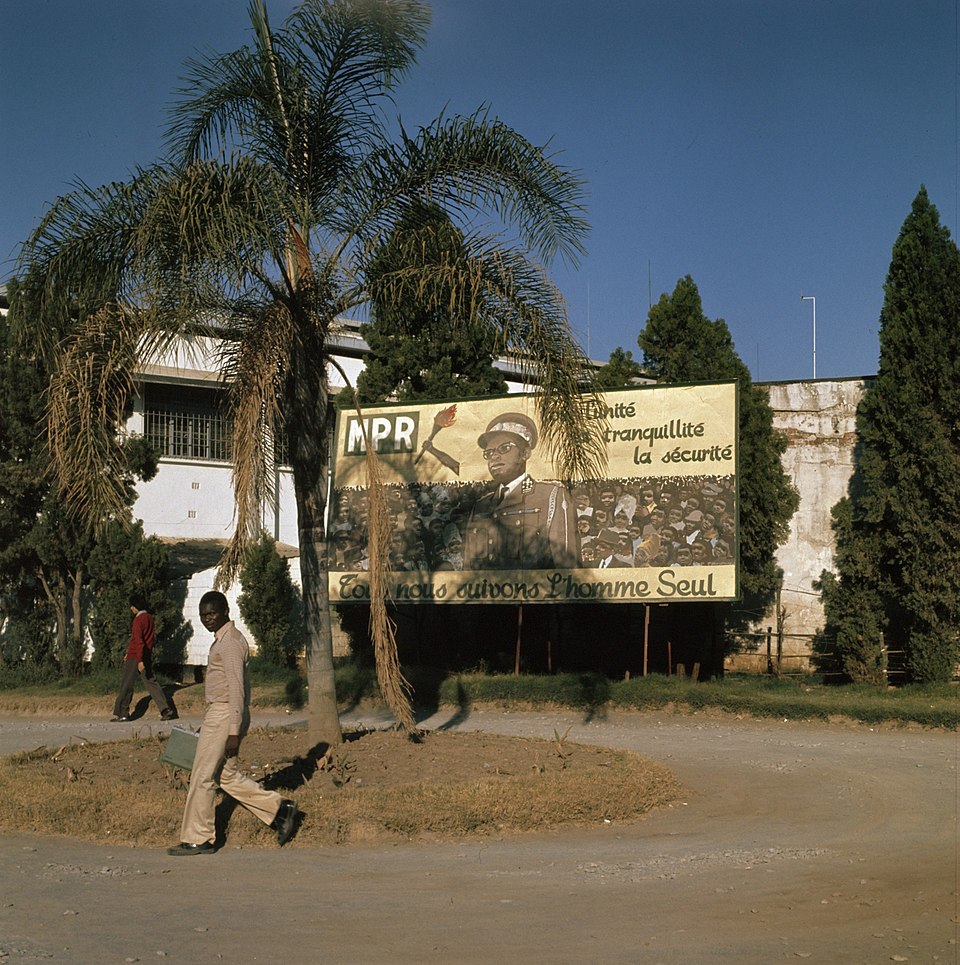

From 1970 onward, the Popular Movement of the Revolution (MPR) was proclaimed the sole party and “nurturing father of the nation.” All political activity outside it became illegal. Schools, factories, villages—social life was framed by the MPR. Slogans—“Serve the people,” “Unity, justice, peace”—punctuated daily life. Zaire ceased to be a pluralist republic; it became a party-state fused with Mobutu’s person.

Through posters, uniforms, and grand ceremonies, Mobutu staged himself as “Father of the Nation,” “Guide,” and “Leopard.” His portraits flooded public buildings; speeches aired nonstop; every success was credited to his genius. Carefully orchestrated displays of fervor constructed a parallel reality in which Mobutu became synonymous with Zaire.

Zairianization was not merely cultural reform; it was a governing tool—channeling social frustrations into identity projects, marginalizing opponents as enemies of “authenticity,” flattering national pride while consolidating authoritarian rule.

Regime architecture: army, services, clienteles, “white elephants”

From the outset, Mobutu knew no regime endures without loyalty of arms. The national army became his close guard and control instrument. Senior officers—often from his native Équateur—were chosen less for competence than for personal fidelity. Deployments signaled authority; loyalty was to Mobutu, not the state.

In parallel, feared services—military intelligence, political police, informant networks—blanketed the territory. Opponents were monitored, intimidated, sometimes eliminated. Fear became a second skin; denunciation and interested loyalty fed permanent control.

Mobutism rested on selective redistribution. Mining contracts, concessions, administrative posts—all were monetized for regime insiders. Gécamines (copper and cobalt) became the power’s slush fund. The goal was not development but buying loyalty, with Mobutu atop the rent pyramid.

He embodied “African modernity” through spectacular projects:

- Lavish presidential palaces in Kinshasa and Gbadolite.

- Oversized international airports to welcome Concorde and Boeing.

- Sports and cultural infrastructures inaugurated with pomp, then abandoned.

These “white elephants” swallowed colossal sums with little benefit to the population—staging modernity rather than rooting it.

The regime formed a pyramid:

- Top: Mobutu, sole source of legitimacy and redistribution.

- First circle: generals, ministers, MPR barons, often from his region.

- Second circle: administrators, governors, SOE chiefs, rewarded for loyalty.

- Base: a population constrained to obedience, mobilized for ceremonies.

Solid in appearance, the structure was riddled with contradictions—an army loyal to a man, an economy serving clientelism, white elephants symbolizing excess—setting the stage for 1990s collapse.

Geopolitics of a pivot: Angola, Shaba, Kolwezi (1975–1978)

By the mid-1970s, Mobutu’s Zaire occupied a strategic position. Its 2,300 km border with Angola made it a buffer between American and Soviet influences. Mobutu became the West’s natural ally, backing Angolan rebels—the FLNA of Holden Roberto (his brother-in-law) and UNITA of Jonas Savimbi—supported by Washington and Pretoria.

Opposite them, the Marxist MPLA relied on Cuban and Soviet aid. Angola became Africa’s hottest Cold War battlefield, with Zaire on the front line.

In March 1977, thousands of Katangan gendarmes exiled in Angola, backed by the MPLA and Cuban allies, crossed into Shaba (former Katanga) aiming to topple Mobutu by striking his mineral heartland. Caught off guard, Mobutu called on allies. With Moroccan help, supported by France and the U.S., the offensive was repelled, bolstering Mobutu’s image as Western bulwark.

A year later, the threat returned. In May 1978, rebels seized Kolwezi, the cobalt capital, taking hundreds of Europeans and local workers hostage. France immediately deployed the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2e REP). Within days, rebels were crushed and hostages freed. Images of French paratroopers circling the globe confirmed Western resolve. For Mobutu, it was political victory—proof of indispensability.

These crises strengthened Mobutu in Western eyes, unleashing aid. Yet dependence exposed fragility: without external support, Zaire could not secure its own provinces.

Kleptocracy and crisis: from hyperinflation to the IMF (1970s–1980s)

Photo courtesy of the White House – David Valdez

Behind Gbadolite’s splendor and authenticity rhetoric lay a simple logic: plunder to redistribute. Public coffers merged with the president’s personal estate. Mining contracts, customs taxes, oil revenues, and foreign aid fed the apex of loyalty.

Diplomats and journalists coined a blunt word: kleptocracy. Mobutu made no secret of it—“If you want to steal, steal a little, but intelligently,” he reportedly told ministers. Corruption became the rule.

In 1979, Erwin Blumenthal, a former German official seconded to the IMF, wrote a famous report as adviser to the National Bank of Zaire: reform was impossible while Mobutu remained—

“One cannot prevent Mobutu from looting any more than one can prevent a cat from catching mice.”

The 1980s plunged the economy into a deadly spiral:

- Hyperinflation destroyed the zaire’s credibility.

- Terms-of-trade collapse (copper, cobalt) drained revenues.

- Debt burden devoured the budget.

For citizens: unpaid wages, decaying infrastructure, mass poverty; the state ceased basic functions.

Turning to the IMF and World Bank, Zaire adopted structural adjustment—cuts, liberalization, subsidy reductions. In practice, misery deepened: layoffs, school and hospital closures, higher prices.

The contrast was stark:

- Above: a sheltered elite, palaces and European hospitals.

- Below: survival via informal economies, market women and parallel networks.

Society under surveillance: universities, media, justice

In 1969, students at Lovanium University protested living costs and authoritarianism; repression was brutal—dozens killed. From then on, educated youth were seen as threats. Campuses became protest hubs periodically closed, purged, silenced by fear.

Media became regime megaphones. Radio-Zaire and Télé-Zaire looped the Guide’s speeches; papers led with his activities. Independent journalists were muzzled or exiled. Information served authoritarian pedagogy—unity, authenticity, omnipresence.

Justice bent to politics. Opposition trials were swift and closed; verdicts taught lessons. In Makala and Ndolo prisons, political detainees endured inhuman conditions. The carceral system became collective intimidation.

Ordinary citizens lived in constant fear. An imprudent remark, an insolent joke, a clandestine pamphlet could mean arrest. MPR cells pervaded neighborhoods and villages; denunciation loomed.

The turn, 1989–1992: end of the cold war, multiparty politics, CNS

By the late 1980s, Zaire lost its main asset—anti-communist bulwark status. With the Berlin Wall’s fall and Soviet collapse, Western need for a central pawn evaporated. Aid dried up; Mobutu stood exposed.

Under international pressure and economic collapse, Mobutu announced the end of the single party in April 1990. Multiparty politics were legalized—but largely cosmetic. Still, civil society, churches, and students reclaimed voice.

In 1991, the Sovereign National Conference (CNS) convened, inspired by Benin’s transition—nearly 3,000 delegates from parties, unions, associations, churches. Intended to refound institutions, it became a moral tribunal of Mobutism, exposing decades of corruption and repression. Mobutu obstructed but could not stop it.

Signals were clear: France withdrew military cooperants; U.S. aid shrank; the IMF suspended disbursements. Mobutu maneuvered—promises, PM reshuffles, divide-and-rule—but invincibility cracked.

Rwanda, AFDL, and the first Congo war (1994–1997)

The 1994 Rwandan genocide reshaped the region. After the RPF’s victory, nearly a million Hutu refugees—including perpetrators—fled into eastern Zaire. Kivu became a powder keg; camps turned into bases for ex-FAR and Interahamwe raids into Rwanda. A weakened Mobutu lost border control.

Rwanda and Uganda backed the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, long marginal. Well-armed columns advanced with Rwandan and Ugandan officers. A regional war unfolded on Zairian soil.

From late 1996, the AFDL advanced swiftly—from Kivu to Kisangani, then diamond-rich Mbuji-Mayi. The corrupt, disordered Zairian army disintegrated; cities fell without resistance. Long-abandoned populations sometimes welcomed rebels.

In May 1997, the AFDL reached the capital. Sick with prostate cancer and isolated, Mobutu fled. On May 17, rebels entered Kinshasa without real fighting. After thirty-two years, the person-state collapsed in days.

Nelson Mandela attempted mediation aboard a South African vessel off Pointe-Noire; talks failed. The Leopard’s hour had passed. The fall ushered in a new era—the Congo as epicenter of African wars.

Exile and end: Togo → Morocco

In May 1997, Mobutu fled Kinshasa aboard his presidential plane. First refuge: Togo, welcomed by Gnassingbé Eyadéma; then, weakened and ill, Morocco. In Rabat, hosted by King Hassan II, the once all-powerful ruler lived discreetly. On September 7, 1997, Mobutu died in exile at 66, without seeing his country again.

His death ended an era—the Zaire person-state—but opened another, under Laurent-Désiré Kabila, amid renewed wars. In Gbadolite, palaces fell to ruin—overgrown gardens, eroded frescoes, cracked runways—bearing witness to vanished glory. Memory remains ambivalent: “Father of the Nation” for some, despot who left a drained country for others. His body lies far from the Congo River—ultimate symbol of exile.

Legacies, controversies, memory

From the 1980s, international press portrayed Mobutu among the world’s richest. Estimates of his fortune—billions—vary.

- 1991, Washington Post: $4–5 billion.

- 1997, Le Monde: $3–4 billion.

- 2000s, Swiss proceedings on frozen assets suggested more modest sums.

He owned villas in France, residences near Lake Geneva, properties in Belgium—some seized, others left to heirs. Debates over restitution of “ill-gotten gains” resurfaced in 2007–2008; legal complexity stalled returns.

Mobutu was also an international actor:

- Alleged gifts to Western leaders—gold watches, cash—reported, rarely proven.

- Israel: discreet military cooperation in the 1980s.

- China vs. USSR: pragmatic ties with Beijing while staying Western-aligned.

Twenty-five years on, memory divides—nostalgia for order and identity versus symbol of corruption and state failure. Gbadolite’s ruins draw researchers and journalists, staging the memory of a man who sought to merge personal destiny with national history—and ended in exile.

The leopard’s shadow

Mobutu Sese Seko embodied one of postcolonial Africa’s most striking trajectories. Rising from the Force Publique and journalism, he built a person-state, fusing his fate with Congo-Zaire’s. For over three decades, he ruled by force, clientelism, and identity theater—Western bulwark, father of the nation, supreme guide.

Behind the flamboyance—Concorde at Gbadolite, mandatory abacost, MPR slogans—lay a system rotted by contradiction. The Cold War gave Mobutu his role; its end sealed his fall. Institutionalized kleptocracy, mass impoverishment, repression, and abandoned white elephants left a heavy legacy. The 1997 collapse was not only a man’s defeat, but a model’s—the state centered on one body without durable institutions.

Mobutu dreamed of embodying Zaire as Louis XIV embodied France—“I am the state.” In reality, when his body left Kinshasa in May 1997, the state collapsed with him. From that void emerged wars that still scar the Democratic Republic of the Congo—proof that the Leopard’s shadow continues to haunt the Congo River’s banks.

Sources

Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges — The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila. A People’s History. Zed Books, 2002.

Young, Crawford & Turner, Thomas — The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Gondola, Charles Didier — The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Callaghy, Thomas — The State-Society Struggle: Zaire in Comparative Perspective. Columbia University Press, 1984.

Wrong, Michela — In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz. HarperCollins, 2001.

Turner, Thomas — Congo Kinshasa. Zed Books, 2007.

Young, Crawford — “Zaire: The Shattered Illusion of the Integral State,” Journal of Modern African Studies, 26(2), 1988.

Lemarchand, René — “Patterns of State Collapse and Reconstruction in Central Africa,” African Studies Review, 34(3), 1991.

Contents

Gbadolite, Capital of a Tropical Dream

Youth, Training, and Early Networks (1930–1960)

Congolese Crisis and the Emergence of the “Key Man” (1960–1965)

November 24, 1965: Seizure of Power and “Stabilization”

Manufacturing a Symbolic Nation: Zairianizing to Govern (1971–1997)

Regime Architecture: Army, Services, Clienteles, “White Elephants”

Geopolitics of a Pivot: Angola, Shaba, Kolwezi (1975–1978)

Kleptocracy and Crisis: From Hyperinflation to the IMF (1970s–1980s)

Society Under Surveillance: Universities, Media, Justice

The Turn, 1989–1992: End of the Cold War, Multiparty Politics, CNS

Rwanda, AFDL, and the First Congo War (1994–1997)

Exile and End: Togo → Morocco

Legacies, Controversies, Memory

The Leopard’s Shadow