A prominent figure of revolutionary Black struggle in the United States, exiled in Cuba for over forty years, Assata Shakur passed away on September 25, 2025, in a heavy diplomatic silence. A former Black Panther activist, clandestine member of the Black Liberation Army, and the first woman to appear on the FBI’s list of terrorists, she leaves behind a life of combat, exile, and controversy. This portrait traces the striking (and unsettling) fate of a woman who became a myth, between Black guerrilla warfare and forbidden memory.

The Death of a Fugitive on Cuban Soil

Assata Olugbala Shakur passed away on September 25, 2025, in Havana, away from the spotlight, in near-complete anonymity. She was 78. No official tribute, no front-page headlines in major Western newspapers. A simple, concise statement from the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed the death of someone whom U.S. authorities had labeled for over forty years as a “terrorist” to capture; alive if possible, dead if necessary.

In the United States, the silence was even more chilling. No statement from the Department of Justice, no word from the FBI, no mention from Congress. As if, in this age of hyper-communication, Assata Shakur’s death was a taboo. And yet, this passing reveals far more than it seems to admit. It symbolically closes one of the most febrile chapters of American political memory: the undeclared war between the state and revolutionary Black movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Assata Shakur was no ordinary dissident. Born JoAnne Byron, she became in the 1970s the federal government’s public enemy number one. An activist in the Black Panther Party and later a leading figure of the armed clandestine wing, the Black Liberation Army (BLA), she embodied what the state never tolerates: a Black woman, intellectual, Marxist, and armed. She was captured, tried, imprisoned, and then escaped in 1979, finding refuge in Cuba, where she became, for some, a heroine of Black resistance, and for others, a criminal protected by a reviled regime.

Her death is not simply that of an elderly woman exiled in a socialist capital. It is the unresolved echo of a fractured America, haunted by the specters of racial struggles, which, half a century after urban uprisings, has still not reconciled with the ideological burns of the 1970s. While Malcolm X’s memory has been partially integrated into the national narrative, Assata’s remains radically incompatible with official amnesia.

It is also, in its way, an American defeat: the only woman ever listed among the FBI’s most wanted terrorists was never captured. She survived the hunt, prison, and exile, and it was in Cuba—not Washington—that she took her last breath.

Birth of a Black Consciousness

Assata Shakur was born under a different name, JoAnne Deborah Byron, on July 16, 1947, in Flushing, Queens, then a mixed neighborhood in a city still fractured by implicit residential segregation. Though she opened her eyes in the North, her childhood was deeply marked by the South. After her parents’ divorce, she was placed with her maternal grandparents in Wilmington, North Carolina—a land of old cotton, but above all, a land of lynchings, Jim Crow, and Sunday sermons on Black obedience. The atmosphere was heavy but formative.

Her mother, a teacher, represented modest stability in an America where educating Black children often meant teaching them to survive rather than dream. But the pivotal figure was Evelyn A. Williams, her aunt. A civil rights activist, lawyer, and intellectual, Evelyn was to Assata what griots are to non-literate peoples: a transmitter of ideas, stories, and worlds. She introduced her to art galleries, museums, books banned in Catholic schools, and above all, the question: why are we told this story and not another?

In her youth, JoAnne briefly attended a Catholic girls’ high school in Manhattan. The uniform was strict, the discipline rigid, the atmosphere overwhelmingly white. The nuns taught her an American history in which Black people were barely mentioned. “I didn’t know how much I had been lied to,” she would later write. The experience was doubly violent: symbolically, she learned that history is a narrative of exclusion; psychologically, she discovered that school could be a tool of racial alienation disguised as education.

Here emerged what might be called her racial cognitive dissonance: an acute awareness of the gap between the America she was taught and the America she saw, where poverty, contempt, and surveillance weighed on her community. This breach, opened in adolescence, would only widen. She would not become an activist by accident, nor a guerrilla by romanticism, but out of historical necessity. The system showed her every day that it was not designed for women like her. She chose, therefore, to reject it entirely.

In this formative moment, the contours of an extraordinary trajectory were already visible: that of a Black intellectual, educated in the school of humiliation, who chose subversion as a way of life. She was not yet Assata, but she was no longer JoAnne.

The Shock of Reality and Entry into Activism

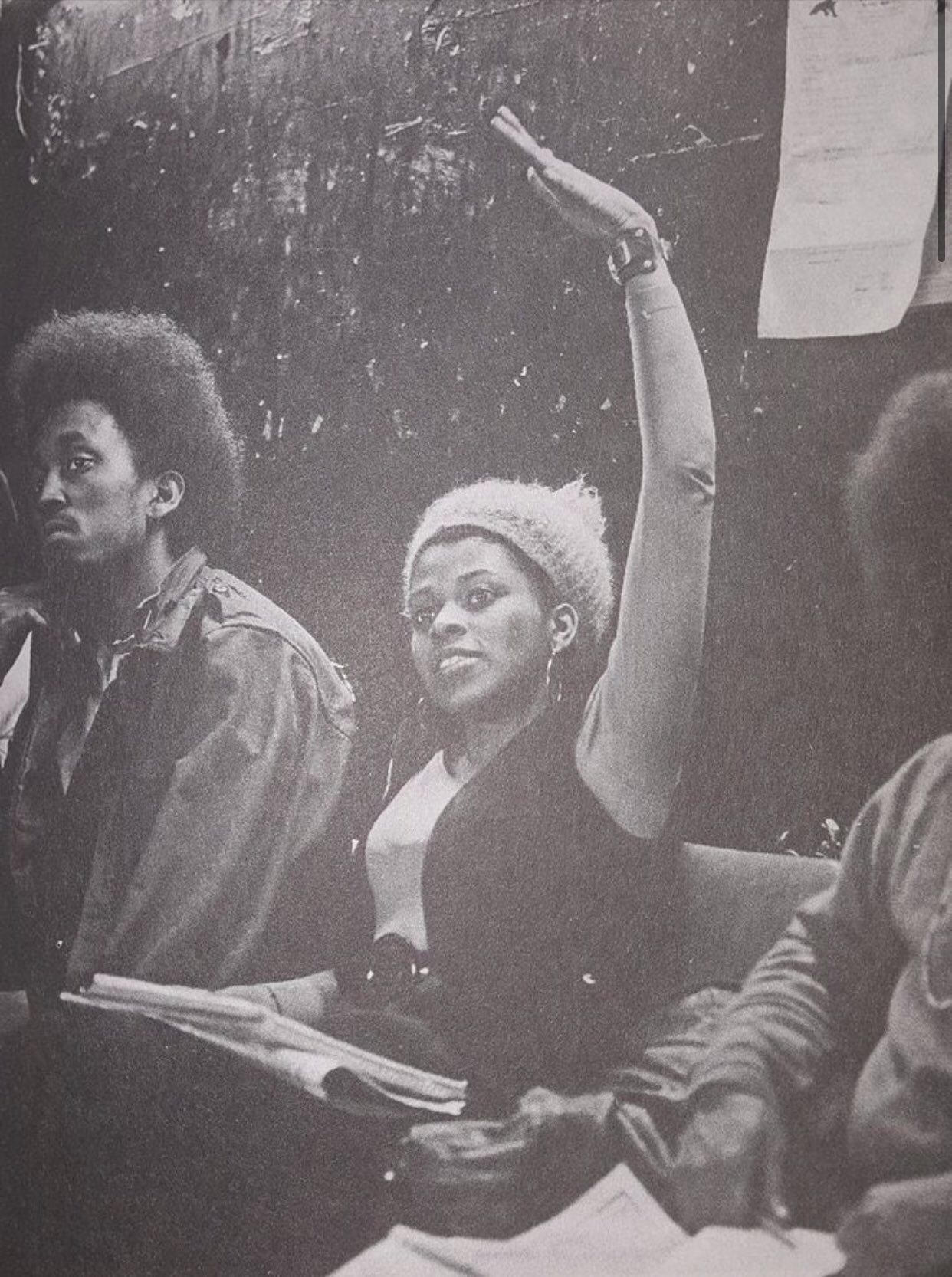

When JoAnne Byron, newly equipped with her GED, entered Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) and later the City College of New York (CCNY), she was still a young Black woman in search of meaning and direction, perhaps a story larger than her own. But in the ferment of the protest-ridden New York campuses of the 1960s, what she discovered was not merely academic knowledge: it was a world on fire, where intellectual neutrality became a form of betrayal.

During a debate on the Vietnam War with African students at Columbia, the spark occurred. They spoke to her of communism, American imperialism, and national liberation. Although fiercely anti-communist by reflex, she found herself unable to articulate what she was criticizing. The shock was profound. She saw herself as what she had unwittingly become: a colonized mind. She later said she felt “like a certified clown” that day. This moment of lucid shame marked the birth of her critical view of American ideological propaganda, especially as delivered by professors and textbooks.

The transition from awareness to action is rapid. In 1967, she was arrested for the first time during a sit-in organized at BMCC with about a hundred students. Their demand was simple, almost naive: more Black professors and the establishment of an African-American studies program. But the administration saw it as a threat. The doors were chained, the protesters surrounded, and the police intervened. JoAnne was handcuffed. It was only a minor infraction (an arrest for trespassing), but for her, it was a political baptism.

This moment, often relegated to the background in her biography, nevertheless marks a crucial stage. It inaugurated a mode of action that would never leave her: the refusal to bow to an institution perceived as structurally unjust. It was not yet going underground, nor armed struggle. But it was already dissent. Surface-level, still legal dissent, raising the following question: when does moral protest become political confrontation? When does protest cease to be a right and become a crime?

In New York lecture halls, she also discovered what libraries had until then carefully hidden: Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Kwame Nkrumah, Malcolm X. This pantheon of decolonial thinkers became her compass. It is here that, quietly, the transformation into Assata begins.

Pan-africanism and radicalization

After intellectual awakening comes the shift to concrete engagement. In the late 1960s, JoAnne Byron (who had not yet taken the name Assata) joined the Black Panther Party (BPP), then at the height of its media and political influence. In Harlem, she coordinated community programs: free breakfasts for children, free health clinics, popular education. The slogan was clear: “Serve the people.” For a Black youth despised by the state, the Panthers represented a form of self-government.

But very quickly, behind the militant facade, JoAnne perceived flaws: the pervasive sexism of male cadres, the obsession with martial confrontation, and above all, the lack of real knowledge of African and African-American history among some leaders. The rhetoric was radical, the weapons visible, but the theoretical background often poor. She faced a structure she judged riddled with ego, internal violence, and revolutionary theatrics that struggled to translate into lasting transformation.

This realization led her to an ideological, then organic, break. She left the BPP and joined a more discreet, more radical, and more dangerous group: the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Going underground was no longer an option; it was a strategic necessity. The BLA considered itself heir to Third World liberation movements. Inspiration now came from afar: the Algerian FLN, Viet Cong guerrillas, the nascent FARC. America was no longer seen as an imperfect homeland to be reformed, but as a racial empire to be dismantled.

Radicalization was also nominal: she ceased to be JoAnne, a name she considered that of a slave, to become Assata Olugbala Shakur. “Assata”: “she who struggles” in Arabic via the Africanization of the name Aisha. “Shakur”: “the grateful.” “Olugbala”: “savior,” in Yoruba. Through this nominal gesture, she symbolically detached from America to inscribe herself in another genealogy: that of Black women in struggle, forgotten queens, mothers of oppressed nations.

From then on, weapons replaced pamphlets. Bank robberies, attacks on police stations, targeted assassinations of dealers and officers—all according to an urban guerrilla logic inspired by the Third World but adapted to the American ghetto. The line was clear: if the state is a machine to kill Black people, it must be fought by any means necessary. For the BLA, violence was not a deviation; it was a grammar of liberation.

Assata went underground as one enters a religion. It was a vow, a break, a birth. The ex-Panther became a fugitive; the intellectual became a soldier. The rest of her life (pursuits, trials, imprisonment, exile) would follow from this irreversible choice.

Becoming Assata

Choosing a name is an act of rupture, a gesture of rebirth. When JoAnne Chesimard became Assata Olugbala Shakur, she did not merely reject a surname inherited from a slave past; she adopted a new cosmology. This revolutionary baptism was not folkloric. In her eyes, it was a radical de-Americanization, an ontological refusal to belong to a white empire founded on slavery, dispossession, and forced forgetting.

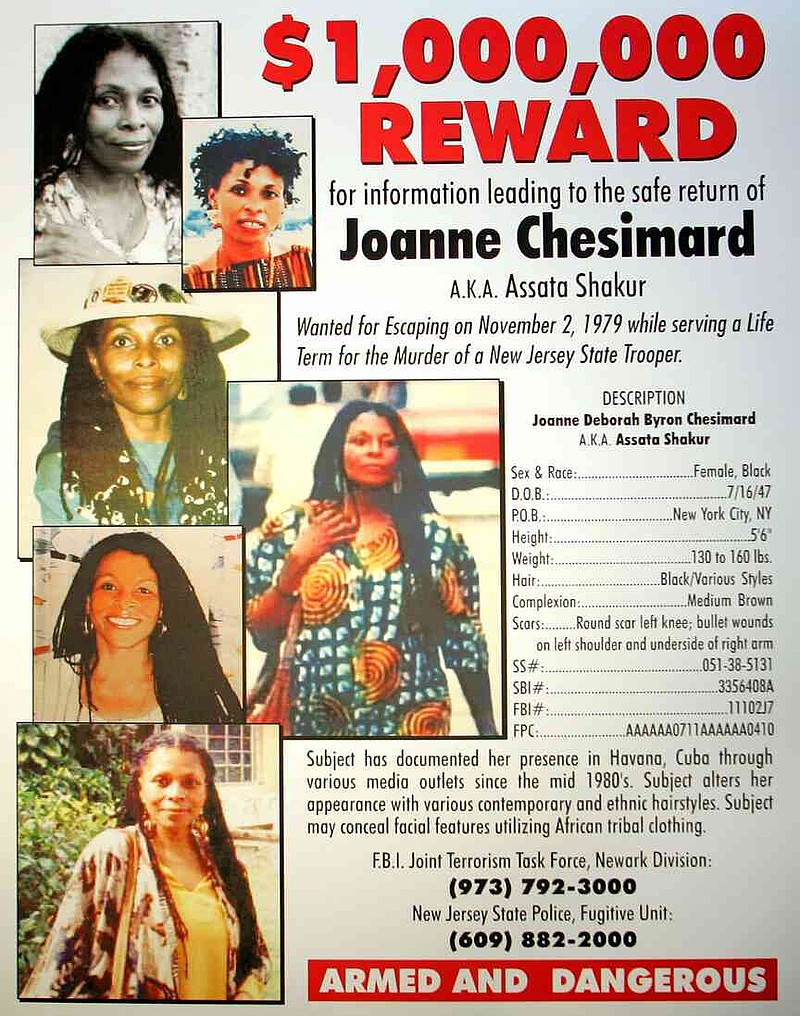

This name change coincided with an intensification of her clandestine activities. Between 1971 and 1973, her name (or rather her image) was associated with a series of violent acts across several states: bank robberies, grenade attacks on police vehicles, armed ambushes. The press dubbed her “America’s most dangerous Black Panther.” The FBI meticulously built her file: photographs, cross-checks, often dubious testimonies, disinformation campaigns. Internal reports designated her as the BLA’s “mother hen,” “the one who holds the group,” “the female brain of the network.” She became a police myth even before being tried.

But who was she really at that moment? An armed Black activist, yes. A political warrior, certainly. But also an ideal target. She embodied everything post-segregation white America was not ready to accept: woman, Black, educated, Marxist, on the run. Her body became a symbolic battlefield. The fact that she survived multiple shootings was presented as proof of her danger. Even her beauty was perceived as a weapon. As often in state repression narratives, the female figure is both demonized and eroticized, reduced to an elusive threat.

Assata, however, did not claim all the acts attributed to her. She admitted there were “expropriations,” that armed struggle had its reasons. But she denied shooting police officers, denied murders, contested evidence, accused the state of fabricating files to neutralize radical Black dissent. She invoked COINTELPRO, the FBI counterintelligence program designed to infiltrate, discredit, and dismantle Black organizations. It was not she, she said, who declared war—it was the state.

The turning point approached. She was everywhere and nowhere; her image circulated on “Wanted” posters, her legend growing both on the streets and in FBI offices. Assata Shakur was now more than an activist. She had become the embodiment of a revolutionary Black alternative. In the corridors of power, her mere existence was enough to trigger panic.

May 2, 1973, on the New Jersey Turnpike

It was 12:45 a.m. on May 2, 1973, when a white Pontiac LeMans, registered in Vermont, was stopped on the New Jersey Turnpike near the highway authority’s administrative building. Inside: Sundiata Acoli driving, Zayd Malik Shakur in the back, and in the front passenger seat, a woman later identified as Assata Shakur. The pretext? A defective taillight and slightly excessive speed. The patrol was led by Trooper James Harper, soon joined by his colleague Werner Foerster.

What followed remains one of the most controversial events in American judicial history. According to official reports, after asking Acoli to exit the vehicle, an altercation broke out. Harper claimed that Assata, still in the front seat, drew a gun from her purse and fired, wounding him in the shoulder. Foerster allegedly tried to return fire but was disarmed, then “executed” with his own weapon.

Other accounts (notably Assata’s own) dispute this version. She claimed she raised her hands before being immediately shot, one bullet in her right arm, another in her back. Medical diagnosis confirmed her median nerve in the right arm had been severed: she would have been unable to fire. Independent experts went further: the injuries could only have occurred if her arms were raised at the moment of impact.

After the shooting, Acoli took the wheel, leaving Foerster dead, Harper wounded, Zayd Shakur critically injured (and dying), and Assata agonizing. The car was pursued. Five kilometers later, Acoli fled into the woods. Assata, wounded, raised her bloody hands and was arrested without resistance. Acoli was found 36 hours later, after a manhunt involving helicopters and police dogs.

Inconsistencies quickly piled up: early reports did not mention Foerster’s presence, whose body was found more than an hour later. Weapons found bore no fingerprints of Assata, and ballistic test results were contradictory. Gunpowder residue tests on her hands were negative. Harper’s account, despite being injured and in shock, became the linchpin of the prosecution, despite contradictions.

No matter: the state had decided. They needed a figure to brandish. A radical, armed Black woman associated with the BLA—a perfect scapegoat. Within days, Assata Shakur became Public Enemy No. 1. Her face appeared on wanted posters nationwide. The FBI, already engaged in its war on “Black Radicals,” found in her a totem to be taken down. Doubts, missing evidence, or medical reports did not matter: justice, as often, had already decided before trial.

May 2, 1973, did not just mark a bloody shootout. It sealed the end of an era. The activist became accused, the revolutionary became symbol. The judicial machine would now relentlessly pursue her disappearance, simultaneously freezing her image in history.

Series of trials, political imprisonment, and myth construction

From May 1973, Assata Shakur’s fate unfolded in courts, in jury boxes, in maximum-security cells, and above all, in the media arena where the American state tried to shape the image of a “cop killer,” inseparable from the radical Black threat.

Ten separate indictments were filed against her between 1973 and 1977: bank robberies, attempted murders, kidnappings, shootouts. Seven trials took place. She was acquitted in three cases, including the Brooklyn Manufacturer’s Hanover Trust bank robbery. Three other cases were dropped due to lack of evidence or witness credibility. Only one trial resulted in conviction: the murder of Trooper Werner Foerster during the New Jersey Turnpike shootout. Again, physical evidence was absent, medical expertise in her favor ignored, and the verdict delivered by an all-white jury, several of whom had ties to law enforcement.

Beyond the trials, Assata’s prison treatment shocked international observers. Initially held at Rikers Island, then transferred to various prisons, she was kept in total isolation for 21 months. A solitary woman in a cell designed to break the spirit: lights on 24/7, regular vaginal searches, constant surveillance, deprivation of reading, no human contact. She was often transferred without notice, sometimes even to men’s prisons, under the guise of security.

In 1974, amid this relentless repression, her daughter Kakuya Shakur was born in a medicalized cell, under surveillance more reminiscent of a military camp than a maternity ward. White female guards, she said, beat her immediately after childbirth to convey that she would never be a mother, only a prisoner. The child was immediately taken from her custody. Yet this intimate moment became a political act: the motherhood of a revolutionary Black woman was denied as one denies an elemental right to humanity.

Several international organizations, including a group of jurists commissioned by the UN Human Rights Commission, publicly denounced her conditions as “inhumane and degrading.” Amnesty International, more cautious, did not recognize her as a political prisoner but admitted that her treatment violated international standards.

And yet, despite walls and humiliations, a legend took shape. Support networks organized. “Free Assata” committees emerged in universities. Artists, intellectuals, and activists began to see her not as a criminal but as the living symbol of an America unwilling to reconcile with its racial past.

In the depths of her cell, the myth of Assata was born; a woman judged a hundred times, humiliated a thousand times, refusing to yield. The U.S. government, in attempting to erase her, inadvertently inscribed her into history.

Support from the international revolutionary network

On November 2, 1979, as America celebrated law enforcement, a remarkable chapter unfolded behind the walls of Clinton Correctional Facility for Women, New Jersey. Assata Shakur escaped. The operation resembled a revolutionary thriller. Three members of the Black Liberation Army (BLA), disguised as visitors, drew .45 automatics and threatened guards with a stick of dynamite. In minutes, they seized a van, took hostages, and vanished with the most surveilled inmate in the country.

There were no casualties. No shots fired. No injuries. A silent, brutal, efficient show of force. Behind the operation was a clandestine network of former Panthers, white radicals from the May 19 Communist Organization, and Third World activists. They called it simply: “the Family.”

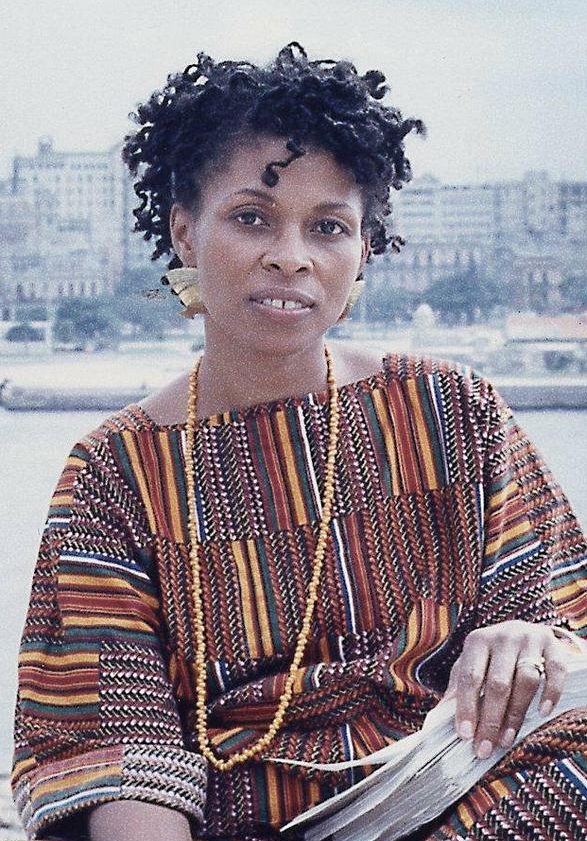

A methodical fugitive life began. Assata literally disappeared. According to FBI documents revealed years later, she first took refuge in Pittsburgh, then was exfiltrated via the Bahamas. Only in 1984 was her presence in Cuba confirmed, where Fidel Castro granted her political asylum, praising the courage of a woman “unjustly persecuted for her beliefs.”

This gesture was not trivial. During the Cold War, Cuba, isolated yet persistent, leveraged Afro-American dissidence to assert itself as an anticolonial refuge. Assata became a geopolitical figure, a diplomatic thorn in Washington’s side. In Cuba, she lived modestly, teaching, translating, and as an exiled intellectual. She published an autobiography, gave a few interviews, but remained largely discreet. The U.S. government had not forgotten.

In 2013, in a post-9/11 climate where the word “terrorism” became a key to condemnation, the FBI officially added Assata Shakur to its Most Wanted Terrorists list. She was the first woman included. A $2 million reward was offered for her capture. Yet she had never killed a civilian, claimed no blind attacks, nor fought in a foreign war theater.

Regardless, in the American security imagination, Assata embodied the specter of an internal revolution, one that, despite time and exile, continued to haunt the racial foundations of the Republic.

Assata, Diaspora Icon or Political Ghost?

In the Black ghettos of Chicago and the progressive campuses of Berkeley, Assata Shakur’s name resonates as a password, an identity marker, a reminder that African-American memory is not dissolved in official history textbooks. For part of the global African diaspora, she is more than a fugitive: she is a survivor, a fighter, living proof that revolt is possible; and sometimes, necessary.

In the 2010s, as the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and many others set U.S. streets ablaze, the Black Lives Matter movement echoed her words, cited her letters, and proclaimed:

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win.”

These words, written by Assata from exile in Cuba, became a generational mantra, chanted in marches, displayed on placards, tattooed on skin.

Revolutionary glory, however, is never straightforward. Assata divides opinion. To law enforcers, she remains a criminal, a cold-blooded murderer. Her lack of public remorse, refusal to submit to republican narratives, and prolonged exile in Cuba (a homeland despised by American conservatism) make her irrecoverable. On the question “resistance or terrorism?” no consensus exists. She crystallizes the fundamental dilemma of any armed struggle: how far can one go without betraying the cause one claims to serve?

Paradoxically, her figure has crossed political boundaries to enter popular culture. Tupac Shakur, often described as her symbolic “godson,” referenced her memory in his lyrics. Artists like Common, Mos Def, and Lauryn Hill reference her journey. African-American professors teach her autobiography as a text of literary resistance. She is studied, sung, tattooed. Her face circulates on T-shirts, between Malcolm X and Angela Davis.

Yet what popular culture absorbs, it tends also to neutralize. Assata’s radicalism (her belief in violence as necessity) is often sanitized. She is cited for her poetry, intelligence, courage—but the Kalashnikovs, the robberies, the clandestinity are forgotten. She is gradually transformed into a sanitized icon, a postmodern martyr easier to admire than understand.

Thus, Assata Shakur remains between two worlds: for some, a mythologized figure of Black struggle, indomitable and untouchable; for others, a political ghost, a remnant of a past best forgotten. But in this memory limbo, one thing is certain: she has never ceased to exist as a living fracture in the American national narrative.

Death in shadow, memory in broad daylight?

On September 25, 2025, Assata Shakur died in Havana at 78. Cuba’s Foreign Ministry communiqué simply cited “age-related complications.” No national tribute, state ceremony, or militant procession. The final breath of a revolutionary was extinguished in diplomatic isolation, far from the flags she once waved.

This silence, heavy with meaning, stretches from the Caribbean to Washington. In the U.S., no official reaction. No presidential message, not even an FBI statement—despite their persistent pursuit. Nothing. As if her death were meant not to mark an end but an erasure. As if the state, in a final symbolic act, wanted to deny her historical dimension forever. Neither celebrated nor damned: deliberately forgotten.

This void raises a critical question: was it erasure or discreditation? Assata was not just a burdensome memory; she was a living political embarrassment. Too radical to be reintegrated into official memory, too famous to be fully denied. Honoring her, even subtly, would legitimize decades of armed struggle. Silencing her maintained the dominant narrative of justice prevailing over racial disorder.

But memory, especially Black memory, does not always obey top-down orders. Already, calls rise here and there for her rehabilitation. Scholars, activists, and artists imagine a future where Assata is recognized not as a “criminal” but as a political prisoner, victim of the deep state and its mechanisms of racial repression. Some compare her exile to Du Bois, others to Angela Davis’s excommunication, until posterity reclassifies them.

For now, she remains in limbo. Neither glorified nor damned. Neither institutionally celebrated nor forgotten by struggles. An underground figure, passed from generation to generation in the margins, activist circles, banned books, or community libraries.

Assata Shakur’s death did not close the case. It reopened it. Through her, America faces a question it constantly avoids: what to do with those who said no, radically, irrevocably, to the national narrative?

The legacy of Assata in contemporary Afro-consciousness

The death of Assata Shakur is not a conclusion. It does not extinguish the fire; it merely relocates it. In the universe of Black memory, fallen figures do not disappear: they transform, migrate into slogans, books, songs, and the dreams of the rebellious. The flesh-and-blood activist Assata now gives way to Assata the metaphor, Assata the black star in the sky of an America that has never stopped turning its back on its own history.

It would be tempting to say that her struggle is over. Tempting—and false. While the U.S. government may have won the judicial battle, it has lost the battle of symbols. The name Assata continues to circulate, carried by young, proud Black voices who see in her not a model to copy, but a cry to extend. Her legacy is that of an unflinching rupture with structures of domination. A visceral refusal to settle for mere survival.

She embodied discomfort. Restlessness. She was the question America did not want to hear, and that even some progressives dared not ask: how far are you willing to go to live free? And if violence is not merely a reaction but a legitimate response to state violence, who decides legitimacy?

In her later writings, Assata no longer advocates armed struggle. Yet she does not renounce it. She speaks of education, dignity, memory. Of the need never to let the enemy dictate your narrative. Her autobiography, published in 1987, remains a declaration of war against amnesia and oppression; a survival manual, but also a guide to clarity and consciousness.

And within its pages, perhaps the truest epitaph can be found, a line that still resonates today as a testament:

“I have been locked by the lawless. Handcuffed by the haters. Gagged by the greedy. And, if I know anything at all, it’s that a wall is just a wall and nothing more at all. It can be broken down.”

The legacy of Assata in contemporary afro-consciousness

The death of Assata Shakur is not a conclusion. It does not extinguish the fire; it merely relocates it. In the universe of Black memory, fallen figures do not disappear: they transform, migrate into slogans, books, songs, and the dreams of the rebellious. The flesh-and-blood activist Assata now gives way to Assata the metaphor, Assata the black star in the sky of an America that has never stopped turning its back on its own history.

It would be tempting to say that her struggle is over. Tempting—and false. While the U.S. government may have won the judicial battle, it has lost the battle of symbols. The name Assata continues to circulate, carried by young, proud Black voices who see in her not a model to copy, but a cry to extend. Her legacy is that of an unflinching rupture with structures of domination. A visceral refusal to settle for mere survival.

She embodied discomfort. Restlessness. She was the question America did not want to hear, and that even some progressives dared not ask: how far are you willing to go to live free? And if violence is not merely a reaction but a legitimate response to state violence, who decides legitimacy?

In her later writings, Assata no longer advocates armed struggle. Yet she does not renounce it. She speaks of education, dignity, memory. Of the need never to let the enemy dictate your narrative. Her autobiography, published in 1987, remains a declaration of war against amnesia and oppression; a survival manual, but also a guide to clarity and consciousness.

And within its pages, perhaps the truest epitaph can be found, a line that still resonates today as a testament:

“I have been locked by the lawless. Handcuffed by the haters. Gagged by the greedy. And, if I know anything at all, it’s that a wall is just a wall and nothing more at all. It can be broken down.”

The death of Assata Shakur closes her life but not her struggle. Does it end the fight? Or, conversely, does it give it a breath life could no longer sustain? In the case of Assata Shakur, the answer is neither biological nor nostalgic. Her physical disappearance in 2025 buries nothing. It metamorphoses. It does not close a cycle; it widens the shadow of an already elusive symbol.

Assata is no longer simply an activist, a guerrilla fighter, or a political exile. She has become a myth. And the nature of myths is to belong to no one, to be passed like flames; hand to hand, never fully extinguished.

Within activist networks, youth movements, Pan-African and decolonial circles, her name is still whispered with respect, defiance, sometimes even fear. Assata represents naked radicalism: the refusal to compromise, the break with legal frameworks when the law becomes complicit in oppression. It is a voice many still prefer not to hear.

And yet, history continues to mention her, by force. Every time police kill without trial. Every time a Black body is hunted like a target. Every time the state dictates to the oppressed the acceptable form of their anger.

Yes, her trajectory divides opinion. But it challenges. It forces the questions that official history avoids: is disobedience a crime? Is uprising always wrong? Is social peace worth submission?

In her memoirs, published in 1987, Assata already hinted at this tension between confinement and liberation, between wall and hope. She wrote, in a poem that has become her testament:

“A wall is just a wall and nothing more at all.

It can be broken down.”

Behind this simple line lies an unbearable truth: power is never final. It can be challenged. It can be overturned. It can, one day, be forgotten.

References

- Shakur, Assata. Assata: An Autobiography, Lawrence Hill Books, 1987.

- FBI Records – The Vault – Assata Shakur, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- May 19th Communist Organization Papers, Tamiment Library, NYU Special Collections.

- Williams, Evelyn. Inadmissible Evidence: The Story of the Battle to Free Assata Shakur, Lawrence Hill Books, 1993.

- Assata Shakur on the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists List, USA Today, 2013.

Table of Contents

- The death of a fugitive on Cuban soil

- Birth of a Black consciousness

- The shock of reality and the entrance into activism

- Pan-Africanism and radicalization

- Becoming Assata

- May 2, 1973, on the New Jersey Turnpike

- Serial trials, political imprisonment, and myth-making

- Support from the international revolutionary network

- Assata, diaspora icon or political ghost?

- Death in shadow, memory in daylight?

- Assata’s legacy in contemporary Afro-consciousness