For a long time, they were silenced, erased from textbooks, and relegated to the margins of official history. Yet, from Abyssinia to the plains of KwaZulu-Natal, from Cayor to Dahomey, African leaders stood firm against European columns and Arab-Muslim raids. Through diplomatic cunning, military discipline, or sheer force, they proved that Africa never surrendered without resistance. From Menelik II to Béhanzin, from Shaka Zulu to Samory Touré, their victories and dignity remind us of a truth too often forgotten: the continent’s history is not only made of defeats, but also of resounding “no’s” etched in steel and blood.

When Africa Says “No”

Drums thundered on the morning of March 1, 1896, on the heights of Adwa, Ethiopia. The sun rose over glowing hills where tens of thousands of fighters assembled. Green, yellow, and red banners snapped in the wind, carried by an army unlike any disciplined European formation. But on that day, facing Italian columns armed with modern rifles and artillery, it was Africa that advanced, confident, conscious of defending its land and honor. The war chants drowned out the roar of cannons. A few hours later, history turned: Menelik II inflicted a crushing defeat on the Italians, offering the continent an enduring symbol—Africa can say “no.”

This moment was not isolated. Throughout the 19th century, as Europe raced through its imperial ambitions and Arab-Muslim raids continued devastating entire regions, African leaders rose up. From Dakar to Zanzibar, from Dahomey to the banks of the Nile, they organized armies, reformed tactics, united peoples, and proved that colonial domination was never a smooth river.

The central question is clear: how, in a context of technological imbalance and multiple aggressions, did certain African strategists manage to contain, repel, or humiliate the powers seeking to enslave them?

African history cannot be reduced to a succession of defeats and submission. It abounds with foundational victories, too often erased from textbooks or relegated to the margins of colonial chronicles. These battles remind us that conquest was never a straightforward military march for outsiders, and that Africa, through the genius of its leaders and the courage of its peoples, repeatedly imposed a resounding “no” on oppression.

1. Emperor Menelik II (Ethiopia, 1844–1913)

At the end of the 19th century, the Horn of Africa became a major theater of colonial rivalry. France, Great Britain, and especially Italy sought to carve out possessions there. The Italians, newly established in Eritrea, imagined themselves as the new conquerors of the Eastern Mediterranean and intended to subjugate the Ethiopian Empire. Their arrogance was fueled by a biased treaty (the famous Treaty of Wuchale, 1889), which, according to the Italian version, made Ethiopia a protectorate. Menelik II, crowned emperor in 1889, categorically rejected this interpretation. Conflict was inevitable.

The confrontation culminated at the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896. Facing 17,000 well-equipped Italians supported by modern artillery, Menelik II fielded nearly 100,000 fighters. Contrary to the image sometimes propagated by colonial propaganda, this was not a disorganized mass but a structured army, equipped with modern weapons obtained through patient diplomacy. Menelik had skillfully exploited rivalries among European powers: he purchased rifles and cannons from both Russia and France, leveraging the contradictions of his adversaries to modernize his arsenal.

On the morning of battle, Ethiopian strategy proved brutally effective. Menelik coordinated regional forces (Amhara, Oromo, Tigrayan), transforming an ethnic mosaic into a united front. The Italians, poorly informed and divided, fell into a series of carefully prepared ambushes. Numerical advantage, combined with intimate knowledge of the mountainous terrain, turned the clash into a disaster for the colonizers. General Oreste Baratieri was defeated; thousands of Italians were killed or captured.

Adwa became a historic turning point. For the first time, an African power inflicted a decisive defeat on a European colonial army. Ethiopia, through this victory, asserted its independence and, alongside Liberia, became one of the only African states not colonized during the Berlin Conference era. Unlike Liberia, which was a product of an American project, Ethiopia prevailed through its own arms, blood, and organization.

Menelik II’s legacy goes beyond military history. He proved that a clear strategy based on modernization and national unity could counter European technological superiority. Adwa became a foundational myth, not only for Ethiopia but for the entire continent: a shining symbol that colonial conquest was never inevitable and that Africa knew how to say “no” at the point of a spear.

2. Queen Yodit Gudit (Ethiopia, 10th century)

Long before Menelik II, Ethiopian history already remembers a formidable and controversial figure: Yodit Gudit, sometimes called Esato. A warrior queen of the 10th century, she allegedly led a bloody uprising against the Christian kingdom of Aksum, one of Africa’s oldest states, established for centuries in the highlands of Tigray.

Tradition presents her as belonging to a marginalized community; some chroniclers describe her as Jewish, others as pagan, and others still as Agaw. This ambiguity highlights the complex religious and ethnic identities of the time. What is certain is that Yodit embodied the anger of the excluded against the established order. By fire and sword, she reportedly devastated Aksum, destroyed its churches, and ended a dynasty nearly a thousand years old.

In popular imagination, Yodit is the archetype of the defiant queen: she refused the spiritual and political domination of a Christian kingdom backed by foreign trading networks. She emerges as an African resistor, opposing both imposed religious hegemony and a central power that marginalized her own peoples.

Modern historiography remains divided. For some, Yodit was a national heroine, the first to assert African sovereignty against an elite colluding with external powers. For others, she was merely a destroyer, an anarchic figure whose brutality ended one of ancient Africa’s shining civilizations. Ethiopian chroniclers, often clerical, immortalized her as a near-demonic figure, accused of attempting to eradicate the Christian faith.

Between popular memory and academic critique, Yodit remains an enigma. But a necessary one: she reminds us that even in Africa’s medieval period, female voices already rose against political, social, and religious oppression. Whether judged a heroine or a destroyer, she embodies the dark yet powerful face of African resistance: the one that says “no,” even if it costs everything to burn it all down.

3. Kocc Barma and Lat Dior Diop (Senegal, 19th century)

In Senegal, the memory of resistance is rooted in both arms and words. Arms belonged to Lat Dior Ngoné Latyr Diop (1842–1886), damel of Cayor, a Wolof warrior prince who dared to say no to French expansion. Words belonged to Kocc Barma Fall (1586–1655), philosopher and sage of Cayor, whose maxims (“a people who extends their hand eventually lose their dignity”) inspired generations of resistors. Together, these two figures form a diptych: one traces the moral path, the other embodies it with the sword.

The 19th century marked French expansion in Senegal. After securing Saint-Louis and Gorée, Paris aimed to penetrate inland, subdue Wolof kingdoms, and open trade routes along the Senegal River. The colonial project took both symbolic and concrete form: the Dakar–Saint-Louis railway, the backbone of conquest. For Lat Dior, yielding land for the railway was surrendering the very soul of Cayor. He steadfastly refused to hand over his lands to French engineers.

Lat Dior did not fight alone. He rallied Wolof cavalry, heirs of a centuries-old martial tradition, as well as traditional contingents armed with spears and trade guns. On several occasions, he inflicted severe defeats on French columns, exploiting his cavalry’s mobility and intimate knowledge of the terrain. Yet, faced with the persistence of better-equipped French forces and constant reinforcements, resistance eventually wore down.

On October 27, 1886, at Dékheulé, Lat Dior fell to French bullets. His death did not extinguish the flame; it rekindled it. He fought not just against an army, but against a global project of subjugation. Choosing the honor of death over the submission of life, he became a symbol.

Today, Lat Dior is celebrated as a symbol of Senegalese dignity. His refusal of the railway became a parable of resistance against colonial projects imposed without consent. His memory continues a continuum where Kocc Barma’s wisdom nourished Lat Dior’s bravery: one warned that dependence is an invisible chain, the other showed that the chain could be broken, even at the cost of blood.

In this sense, 19th-century Cayor was not merely a field of colonial conquest: it was a space of contestation, where words and the sword joined to say a simple, universal word to imperial France: no.

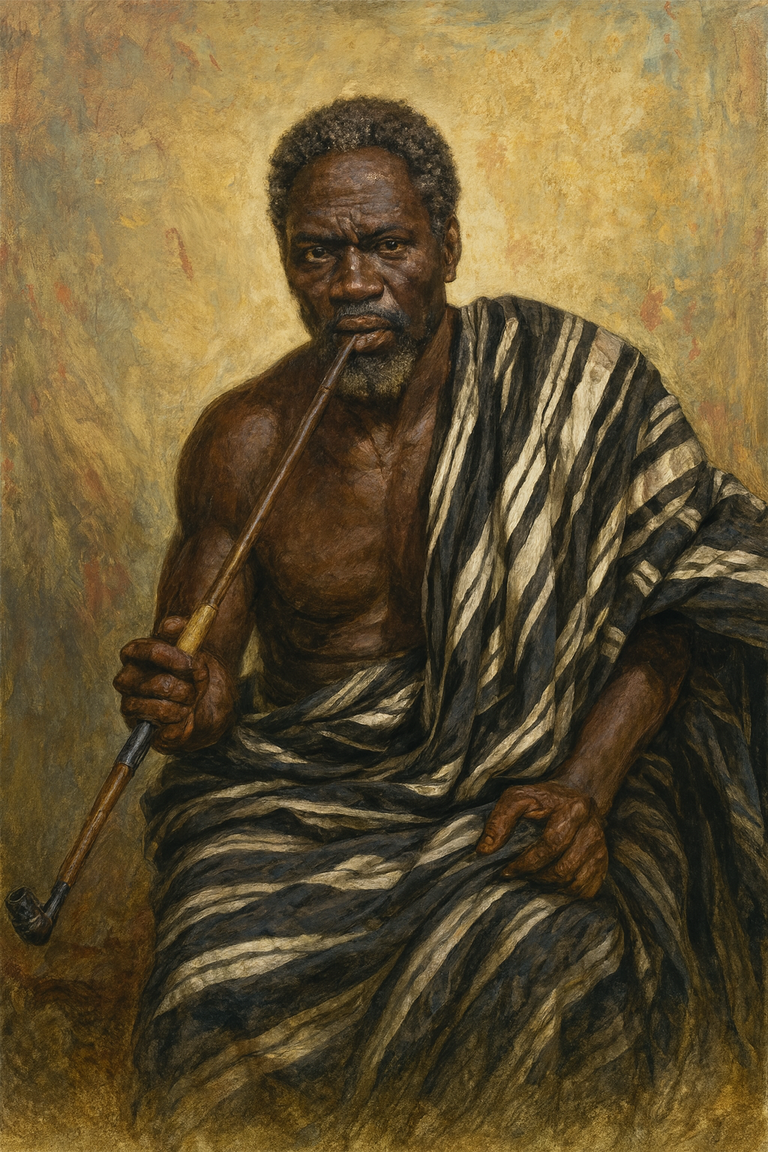

4. Samory Touré (Guinea / Wassoulou Empire, 1830–1900)

Among West Africa’s great resistors, Samory Touré holds a special place. Born around 1830 into a Mandingue family in Upper Guinea, he started as a trader before becoming a warrior, then strategist, and finally the founder of a state: the Wassoulou Empire. His trajectory illustrates a man’s capacity to transform scattered communities into an organized military power, capable of resisting the French colonial machine for over fifteen years.

The context was a West Africa in flux. As traditional kingdoms weakened and Arab and Tukulor slave raids threatened populations, France advanced inexorably from Senegal, seeking to connect the Niger River to the Gulf of Guinea. In this whirlwind, Samory built his empire not only through arms but also through trade: he established a network that allowed him to acquire modern weapons, notably the Gras rifle, a symbol of military modernization.

His army was his masterpiece. Organized into disciplined regiments, trained along quasi-European methods, it numbered up to 30,000 men. The fast, mobile Mandingue cavalry complemented infantry armed with rifles. Samory also innovated in strategy: facing French logistical and technological superiority, he adopted a scorched-earth policy. Villages were burned before the enemy’s arrival, crops destroyed, depriving colonial columns of supplies and forcing them to struggle through hostile territories. This war of movement significantly delayed French advances and inflicted heavy losses on officers from Paris.

But this resistance came at a price. Civilians, displaced and starving, bore a heavy burden. Moreover, the Wassoulou Empire remained fragile, beset by internal rivalries and constant pressure—from the French on one side, the British in Sierra Leone on the other, and rival African armies. In 1898, cornered, Samory was captured by French troops under Captain Gouraud and exiled to Gabon, where he died two years later.

Yet his defeat does not diminish his legacy. For more than a decade, he was the nightmare of French officers, demonstrating that a modern African army could resist one of the most aggressive imperial powers. In West African collective memory, Samory Touré remains the archetype of the resistor: warlord, state-builder, inventive tactician. His struggle embodies a truth too often hidden: colonization was far from a triumphant march; it was a fight, sometimes lost, but always waged with unshakable determination.

5. Shaka Zulu (Southern Africa, 1787–1828)

In the plains of KwaZulu-Natal at the turn of the 19th century, one man radically changed warfare in southern Africa: Shaka Zulu. The illegitimate son of a Zulu chief, marked by exclusion and violence from childhood, he transformed this wound into unprecedented strength, creating one of the continent’s most formidable military systems within a few years.

His genius lay in tactical and organizational revolution. Shaka abandoned traditional throwing weapons in favor of the iklwa, a short spear for close combat. He structured his warriors into regiments (amabutho) grouped by age, subjected to relentless training and near-Spartan discipline. His most famous maneuver, the “bull horn” tactic, encircled the enemy in three moves: a fixing center, two rapid flanking wings, and a reserve ready to strike. In an African context where warfare often meant raids, Shaka imposed frontal, total confrontation aimed at annihilation.

These military innovations gave rise to a rapidly expanding empire. Under his reign, the Zulu dominated KwaZulu-Natal, crushed or absorbed dozens of chiefdoms, and triggered the mfecane (“the scattering”), a major demographic upheaval reshaping southern Africa. Entire populations migrated, fleeing Zulu pressure, destabilizing the region and indirectly facilitating European incursions.

Shaka’s opposition to Europeans was indirect but decisive. By consolidating centralized power and an invincible army, he delayed Boer advances and complicated Portuguese ambitions in the region. Even after his assassination in 1828 by his half-brothers, Zulu military power continued to haunt settlers, culminating later in famous clashes such as the victory of his successors at Isandhlwana (1879) against the British.

Shaka’s legacy is twofold: he is celebrated as a visionary strategist, unifier, and founding father of the Zulu nation, yet his brutal reign, marked by massacres and mass displacement, leaves an ambivalent memory. Nonetheless, his impact on African military history is undeniable: Shaka demonstrated that organization, innovation, and discipline could compensate for material inferiority.

More than two centuries after his birth, his name remains synonymous with power and pride. Shaka Zulu did not merely shape a people; he redrew the geopolitics of southern Africa.

6. Béhanzin Hossu Bowelle (Dahomey, 1844–1906)

In the history of African resistance, few figures embody dignity in the face of colonial arrogance like Béhanzin Hossu Bowelle, the last independent king of Dahomey. He inherited a feared military kingdom in West Africa and ascended the throne in 1889, at a time when France sought to turn the Gulf of Guinea coasts into exclusive spheres of influence.

From the outset, Béhanzin rejected treaties imposed by Paris. Where some African rulers accepted vassalage in exchange for symbolic authority, he chose confrontation. Trade, taxation, access to ports—nothing was negotiable when it came to sovereignty. His uncompromising stance sparked the Dahomey Wars (1890–1894), among the most emblematic clashes of French colonial conquest.

The Dahomey army was not improvised: it was structured, disciplined, and formidable. Its regiments included thousands of fighters, notably the famous Agojié, warrior women Europeans fascinatedly and fearfully called “Amazons.” Armed with rifles and machetes, rigorously trained, they embodied a society where war was a collective affair, irrespective of gender. The presence of these female regiments on the battlefield stunned French observers, proving unyielding determination.

Yet French material superiority eventually prevailed. Heavy artillery, modern rifles, and imperial logistical support gradually wore down resistance. After several bloody campaigns, Abomey fell in 1894. Béhanzin was captured and deported first to Martinique, then Algeria, where he died in 1906.

His exile did not seal a moral defeat. On the contrary, he became a symbol of national pride. His obstinate refusal of treaties and choice of combat over submission inspired generations. In Beninese and African collective memory, Béhanzin embodies the dignity of a king who never bowed to imperialism.

Even today, his figure is inseparable from that of the Agojié, reminding us that African resistance was not only male: women fought with equal fervor to defend their land. Béhanzin Hossu Bowelle, militarily defeated, triumphed morally: he proved that the honor of a people is non-negotiable.

7. Rabah Zobeir (Chad / Borno, 1842–1900)

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, in the plains and savannas of the Lake Chad basin, a figure emerged whose memory still haunts: Rabah Zobeir (Rābiḥ az-Zubayr ibn Faḍlallāh). Born around 1842 in Darfur, a former lieutenant in Sudanese slave armies, he transformed into an empire-builder, imposing authority from Sudan to Chad, fighting both Arab-Muslim raids from the north and the inexorable advance of French colonial columns.

Rabah relied on a formidable military organization. His army, disciplined and mobile, included veteran warriors as well as forcibly conscripted slaves. Through iron and blood, he founded a short-lived but powerful empire capable of rivaling the ancient kingdoms of Borno and Ouaddaï. His campaigns involved constant clashes with Arab-Muslim forces, which he challenged on their own terrain, and a fierce determination to control strategic routes in the central Sahara.

As his power expanded, a new threat emerged: French penetration. From Sudan, Congo, and Algeria, Paris deployed military columns to encircle the Chad basin. Rabah, hardened by years of warfare, refused submission. From 1897 to 1900, he fought battle after battle against French expeditions, inflicting several setbacks on colonial officers. His troops harassed, maneuvered, and burned villages allied with the French in a war of attrition where every victory delayed the inevitable.

The climax came on April 22, 1900, at Kousséri. Rabah faced French columns commanded by Lamy. The battle was fierce, with heavy losses on both sides. Rabah fell in combat, beheaded, his head sent to Paris as a trophy. Lamy himself also perished. This brutal end marked the fall of an empire and the entry of Rabah into legend.

An ambiguous symbol, Rabah was both a ruthless conqueror and a fierce resistor. His use of slavery and brutal methods make him a contested figure. Yet he remains a striking example of Africa’s capacity for tenacious resistance, even in desperate conditions. In the popular imagination of Chad and Sudan, his name is associated with the honor of combat, the determination never to submit, and the truth that even in defeat, Africa never ceased to fight.

Legacies of steel and erased memories

From Abyssinia to the Chad savannas, from Cayor to the plains of KwaZulu-Natal, Africa has continuously produced resisters capable of standing up to external forces. Menelik II, Yodit Gudit, Lat Dior, Samory Touré, Shaka Zulu, Béhanzin, Rabah Zobeir: so many names that testify to the diversity of contexts and enemies faced. Some fought against European imperialism, others against Arab-Muslim raids, and still others against the predatory ambitions of neighboring African powers. Yet they all share a common constant: the determination to say “no,” even if it meant embracing death rather than submission.

And yet, these resistances remain marginalized in school textbooks, when they are not reduced to footnotes. Colonial history, as told in Europe—and sometimes even in Africa—preferred to emphasize the “civilizing mission,” the inevitability of conquest, masking the active, violent, and heroic role of African struggles. This silence is a mutilation of memory.

The legacy of these leaders has not disappeared. It survives in monuments, oral traditions, and national celebrations. In Ethiopia, the victory at Adwa is celebrated each year as a sovereignty festival. In Senegal, the name Lat Dior is synonymous with national dignity. In Benin, the memory of Béhanzin and the Agojie is revived as a symbol of female courage. In KwaZulu-Natal, Shaka is both a myth and a political reference. These traces convey a simple truth: even erased from books, African memory always finds refuge in speech, stone, and ritual.

An immense task remains today: to restore these figures to a central place in African collective imagination. It is not only about celebrating heroes; it is about reminding that freedom was wrested at the cost of blood, that independence is never a gift but a conquest, and that past victories still illuminate present struggles.

Contemporary Africa, confronted with new forms of domination—economic, cultural, and geopolitical—needs these legacies of steel. Not to dwell in nostalgia, but to understand that in every era, men and women refused resignation. Their resounding “no” remains a call: to unity, memory, and dignity.

Notes and References

Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991, Oxford, James Currey, 1991.

Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1975.

Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270–1527, Oxford University Press, 1972.

Cheikh Anta Diop, Histoire générale de l’Afrique, Volume IV: Africa from the 12th to the 16th Century, UNESCO, 1984.

Boubacar Barry, La Sénégambie du XVe au XIXe siècle: traite négrière, Islam et conquête coloniale, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1988.

Ibrahima Thioub, Le Sénégal à l’épreuve de la colonisation, Dakar, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, 1990.

Yves Person, Samori: Une révolution dyula, 3 volumes, Dakar, IFAN, 1968–1975.

Djibril Tamsir Niane, Histoire des Mandingues de l’Ouest: le royaume du Ouassoulou, Paris, Présence Africaine, 1989.

Carolyn Hamilton, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention, Harvard University Press, 1998.

John Wright, The Mfecane: The Making and Unmaking of an Academic Myth, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 1989.

Edna Bay, Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1998.

I. A. Akinjogbin, Dahomey and Its Neighbours, 1708–1818, Cambridge University Press, 1967.

Jacques F. A. Maquet, Civilisations of Black Africa, Oxford University Press, 1972.

Yves Urvoy, Histoire de l’Afrique de l’Ouest, Paris, Payot, 1949 (chapters on Rabah Zobeir and Borno).

Mario Azevedo, Historical Dictionary of Chad, Metuchen, Scarecrow Press, 1998.

Histoire générale de l’Afrique, Volume VI: Africa from the 19th Century to World War I, UNESCO, 1985.

Elikia M’Bokolo, Afrique noire: histoire et civilisation, Paris, Hatier, 1992.

Joseph Ki-Zerbo (dir.), Histoire de l’Afrique noire d’hier à demain, Paris, Hatier, 1978.

François-Xavier Fauvelle, Le Rhinocéros d’or: Histoires du Moyen Âge africain, Paris, Alma, 2013 (for critical and historiographical grounding).

Contents

- When Africa Says “No”

- Emperor Menelik II (Ethiopia, 1844–1913)

- Queen Yodit Gudit (Ethiopia, 10th century)

- Kocc Barma and Lat Dior Diop (Senegal, 19th century)

- Samory Touré (Guinea / Wassoulou Empire, 1830–1900)

- Shaka Zulu (Southern Africa, 1787–1828)

- Béhanzin Hossu Bowelle (Dahomey, 1844–1906)

- Rabah Zobeir (Chad / Borno, 1842–1900)

- Legacies of Steel and Erased Memories

- Notes and References