Long relegated to the margins of historical narratives, the trans-Saharan slave trade nonetheless deported between 6 and 10 million Africans. Desert routes, sexual slavery, castration, complicit silences: a repressed memory that still unsettles, caught between religious taboos, competing memories, and the absence of reparation.

A selective memory

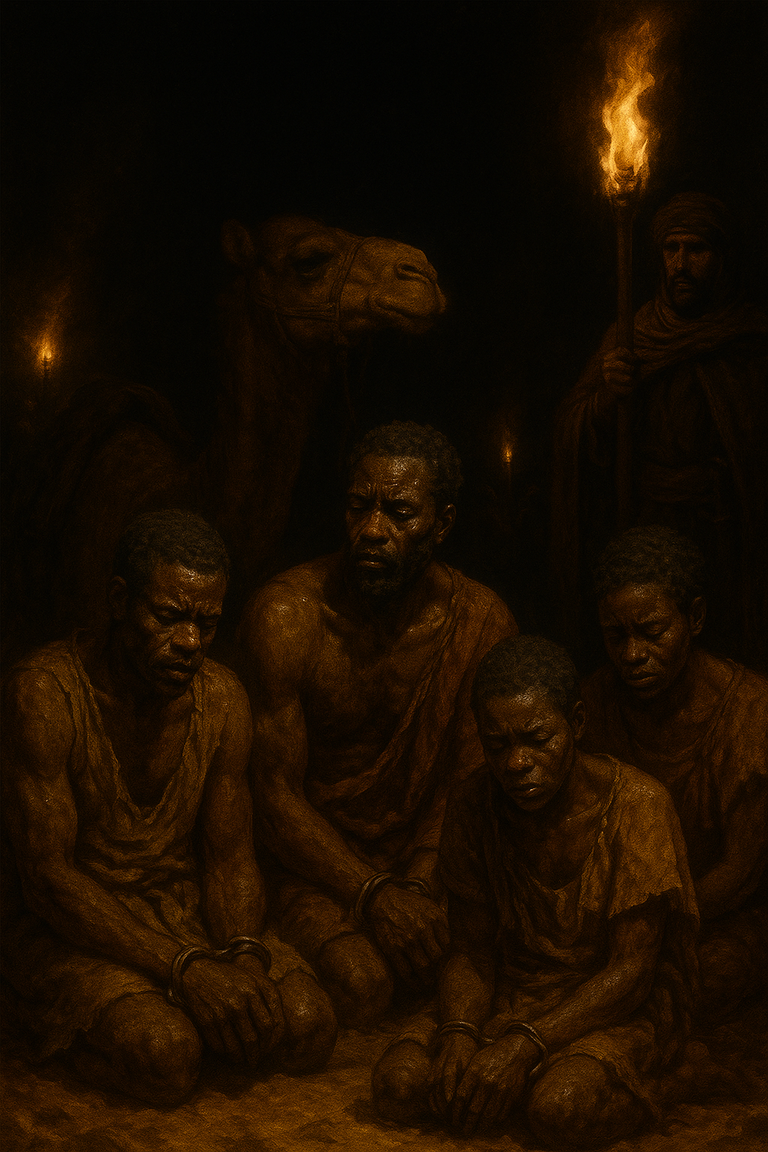

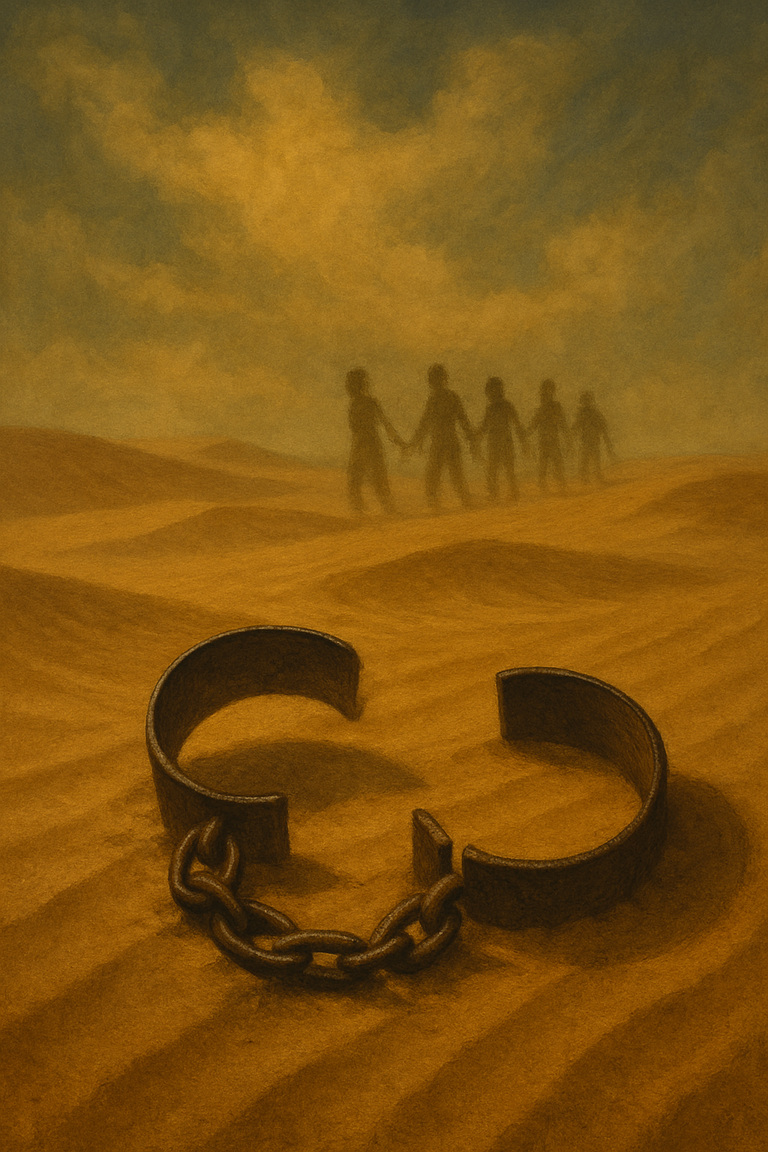

The wind blows endlessly over the dunes, sweeping away every trace of passage. Yet once, these invisible tracks were trodden by thousands of feet. Chained two by two: men, women, children. Their silhouettes stretched beneath the crushing sun, in a silence broken only by the shouts of masters and the metallic clatter of irons. Caravans of tears, swallowed by the indifference of history.

Much is said about the triangular trade, the deportation of Africans to the Americas, the chains of the Atlantic. But what of the chains of the desert? Of that other trade, even older, which saw millions of Africans cross the Sahara to be sold in the markets of Algiers, Cairo, Tripoli, Mecca? In school textbooks, this page is barely mentioned. In official speeches, it is often sidestepped. In people’s minds, it remains vague, almost taboo.

Why this silence? Why does this memory—yet essential—remain on the periphery of our collective narratives? Because it unsettles. It disrupts certainties. It highlights African complicities, Arab responsibilities, cultural and religious continuities that some prefer not to question. It disturbs the idea of a South always victim and a North always guilty. It fractures binary divides, comforting stories, and convenient political postures.

The trans-Saharan slave trade fits neither the usual chronology nor geography of slavery narratives. It predates the transatlantic trade. It lasted longer. It affected as many, if not more, lives. And yet it remains marginal—rendered invisible, as if the desert sands had buried memory itself.

But a forgotten memory is not an erased one. It waits, patiently, beneath the surface. And today, it demands to be unearthed. Not to divide, but to understand. Not to accuse, but to repair. Not to turn back time, but so that silence is never again complicit with injustice.

For historical truth is not an option. It is a duty.

Ancient origins of an economy of capture

Long before galleons crossed the Atlantic, long before the ports of Nantes or Liverpool became hubs of human commerce, another economy of capture took root on the African continent. It was woven—slowly and deeply—into the sands of the Sahara and the valleys of the Nile, to the rhythm of conquests, raids, and caravans.

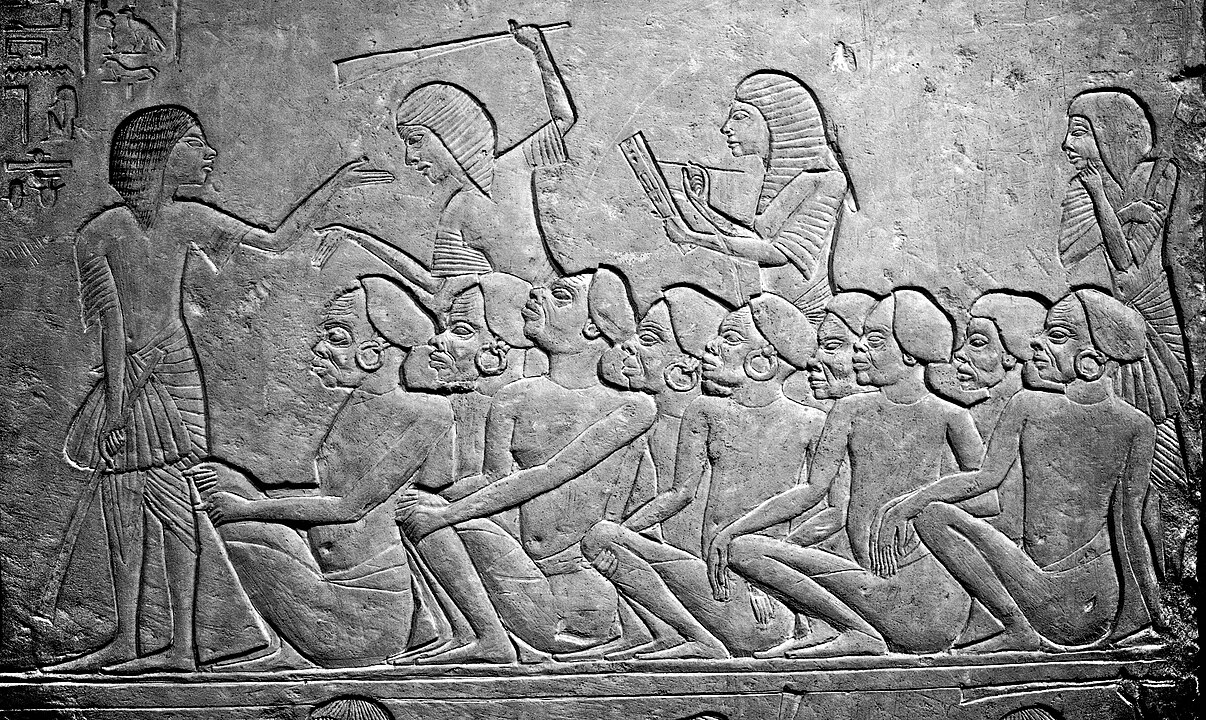

In Antiquity, the great civilizations of the region (the Garamantes, Egyptians, Carthaginians, then Romans) already integrated the African human being into a commercial system in which he was not a subject, but an object. Among the Garamantes, a Saharan people of present-day Libya, slaves were torn from sub-Saharan populations and used to cultivate oases. Herodotus, the Greek historian of the 5th century BCE, mentions their expeditions southward to capture Black people—evidence of an early, structured slave trade organized around the desert.

The Egyptians and later the Romans practiced mass enslavement during wars. Prisoners of war, including those from Nubia or Ethiopia, became an essential servile workforce for imperial administration. In ancient accounts, Black skin gradually became a marker of otherness—associated with exoticism, but also with domination.

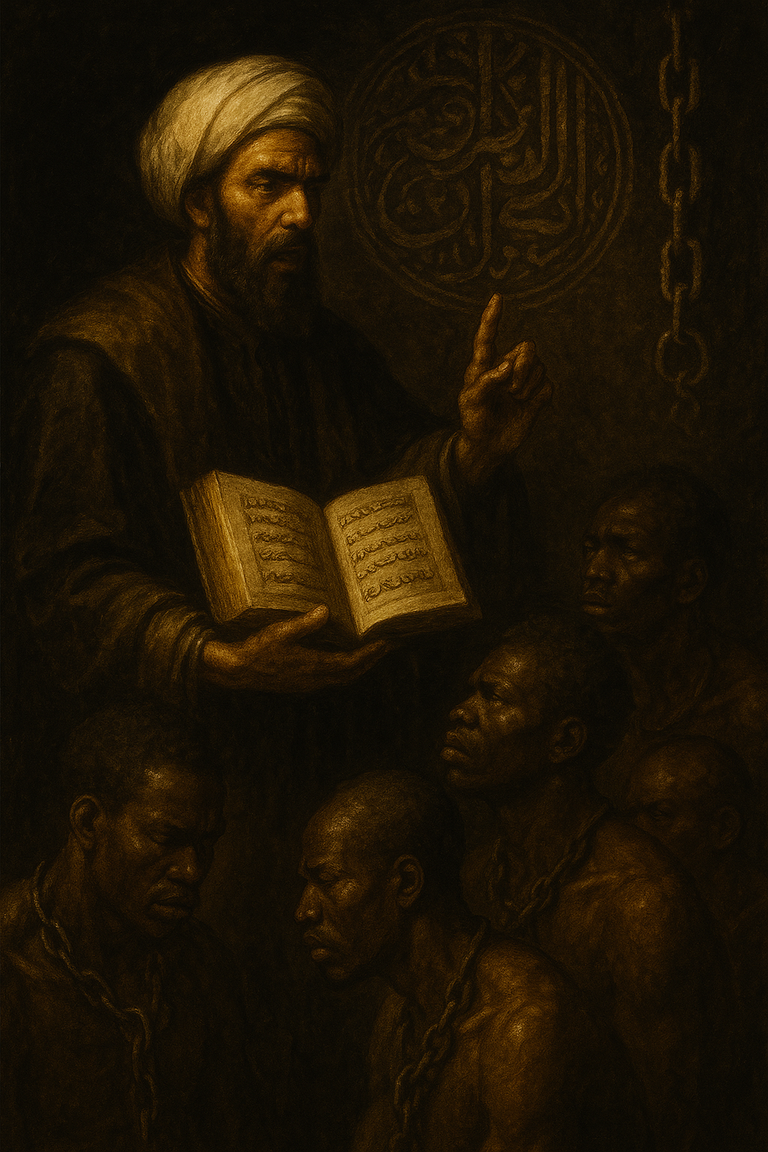

From the 7th century onward, with the rapid expansion of Islam, a change in scale and structure occurred. The arrival of Arabs in North Africa did more than spread a new faith; it transformed systems of exchange and power. The desert became a major commercial axis. Saharan routes, once rudimentary, grew denser and professionalized. Slaves—previously war captives or byproducts of conflict—became a strategic commodity, sought for their labor or symbolic value.

Islamized, the trans-Saharan trade took on a new form. Legal and religious treatises regulated the use of slaves while justifying their enslavement in certain cases (non-Muslims, prisoners, etc.). Cities such as Gao, Timbuktu, or Zawila became crossroads of a traffic where gold, salt, ivory—and human lives—intersected. The human being became a good like any other, a unit of account in an economy spiritually justified yet ethically troubling.

This shift toward an organized commercial slavery—with its routes, markets, and religious rationalizations—laid the foundations of a system that would last more than thirteen centuries. Africa, on the margins of the great Islamic empires, became an immense reservoir of human flesh to supply the societies of the Maghreb, the Near East, and even Central Asia.

Thus, long before the word “trade” entered European lexicons, another mercantile world had already taken shape—with its victims, its profits, and its silences.

The system of the trans-saharan slave trade

Mapping pain: the logistics of a forgotten crime

At the heart of one of the world’s largest deserts, a network of shadows and blades stretched like a silent web: the trans-Saharan slave trade. More than a route, it was a complex, well-oiled, implacable system that turned dunes into corridors of servitude. Between the 8th and the 19th centuries, several million men, women, and children were torn from sub-Saharan Africa to be sold in slave markets across North Africa, the Levant, and even as far as India and Persia.

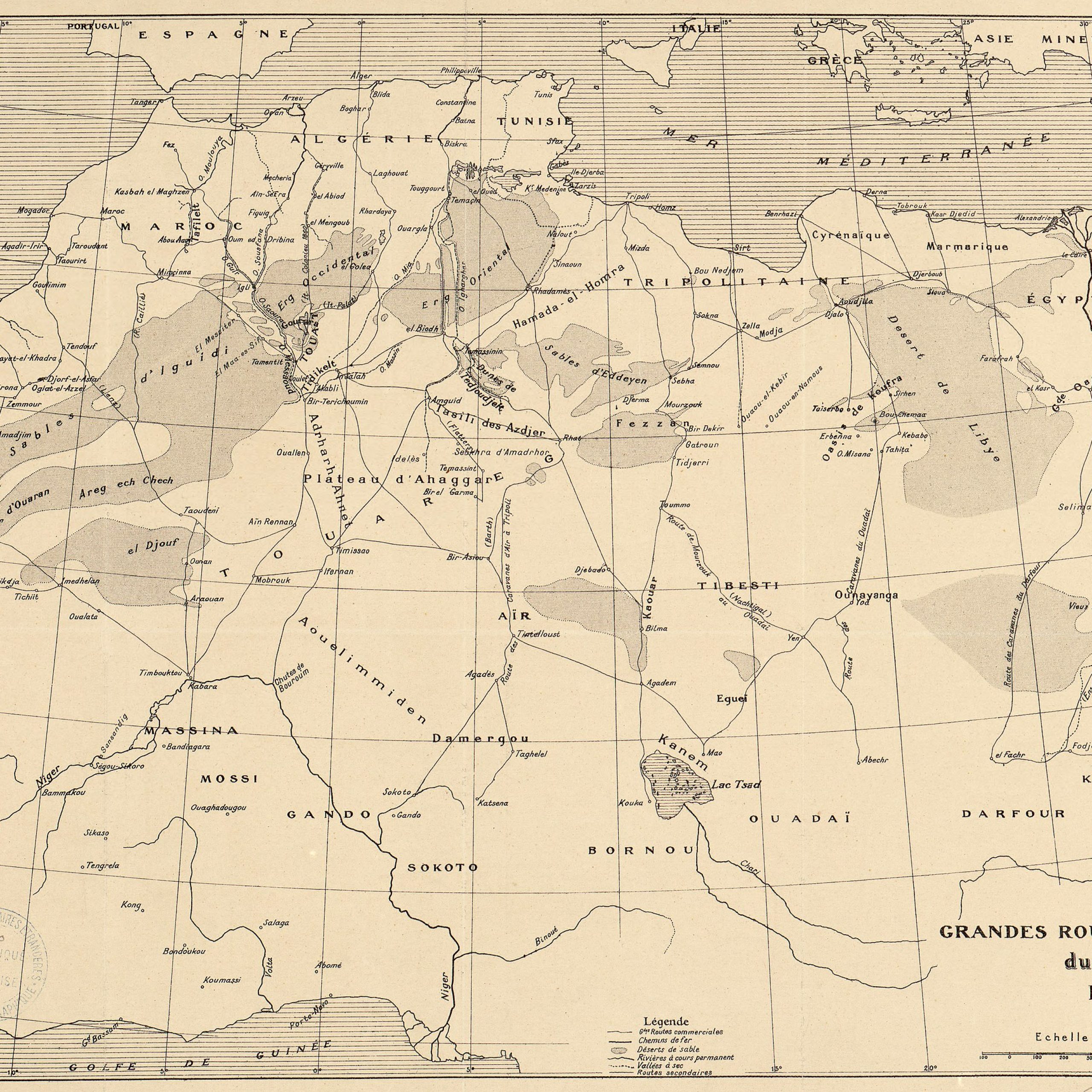

The main caravan routes are now invisible scars on modern maps. The most famous linked Tripoli to Lake Chad via Fezzan and the kingdom of Bornu. Another crossed the desert between Ghadamès and Gao along the southern banks of the Niger River. Others linked Timbuktu to Algiers or departed from Zawila toward Darfur. Each route bore its share of suffering, its bodies broken beneath the sun.

These were not simple commercial journeys. They were a tentacular organization involving Arab merchants, Tuareg caravan leaders, Islamized African kings, and numerous local powers that profited from it. The trans-Saharan slave trade was no historical accident; it was conceived, structured, and integrated into the region’s political economy.

Contrary to common misconceptions, raids were not solely the work of outsiders. Many tribal chiefs or Islamized kingdoms (such as Kanem-Bornu, Wadai, or certain Hausa states) actively participated in this chain of predation. They organized military campaigns, captured non-Islamized populations (often deemed “infidels”), and resold them for textiles, weapons, salt, or horses.

Power, in many cases, was exercised through human capture. Owning slaves was a sign of wealth, power, and belonging to a “civilized” world by the standards of the time. Some states even made it a structural pillar of their diplomacy with northern powers.

In this geography of despair, oases were no havens of peace. Kufra, Awjila, Ghat, Agadez, Bilma—poetic names for places that became hubs of human commerce. Caravans resupplied there, organized contingents, and sometimes sorted captives. Those deemed too weak were abandoned, sold locally, or left to die.

These oases functioned as open-air warehouses. Slaves were sometimes held while awaiting the right buyer or moment to cross the dunes. The desert forgives nothing. Violence, hunger, nocturnal cold, daytime heat, and systematic abuse were the price of the journey.

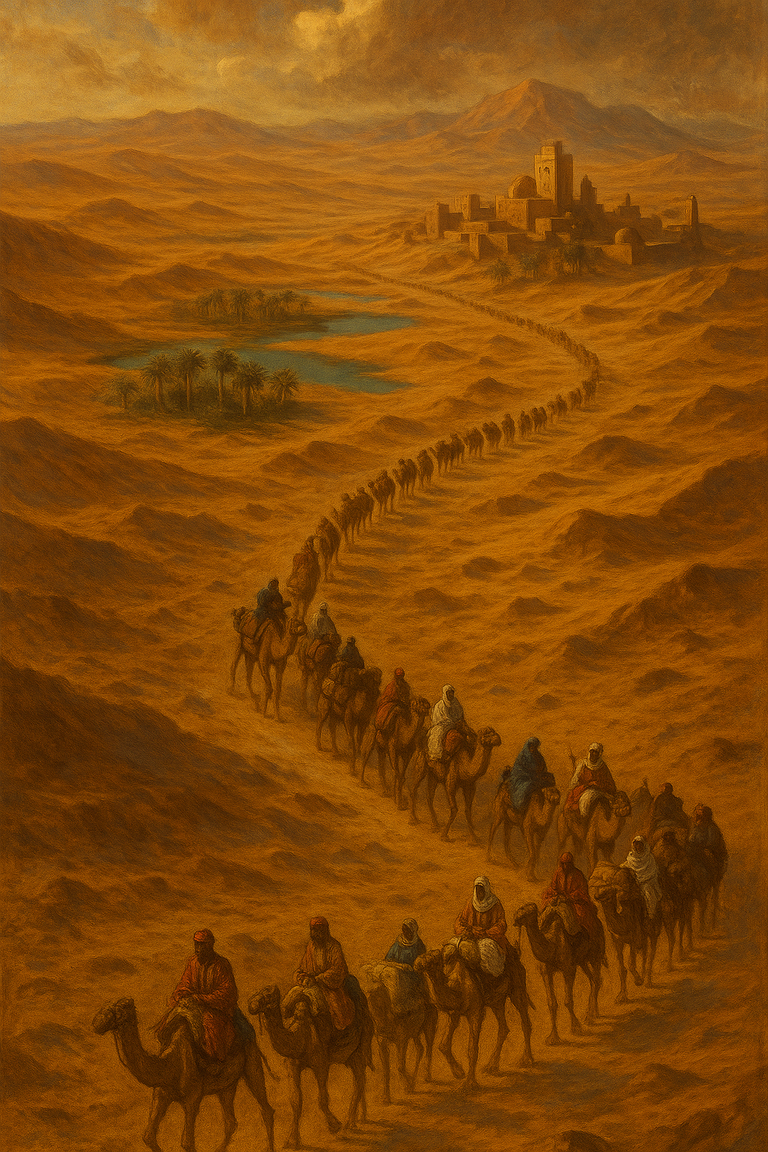

The figures are staggering. An average caravan comprised between 1,000 and 3,000 camels—sometimes far more—and up to several hundred captives on foot, chained two by two, shackled, starving. A month, sometimes two, was required to reach the final destination. Mortality rates were horrific: between 20% and 50% of captives died en route—of thirst, malnutrition, disease, or were simply executed to avoid slowing the column.

Women endured specific forms of violence. Many were reduced to sexual servitude, sold as concubines or domestic workers in harems. Children were selected for their supposed docility or castrated—an atrocious practice aimed at producing eunuchs for palaces or armies.

None of this would have been possible without the dromedary, the logistical “engine” par excellence of this trade. Introduced on a large scale from the first millennium onward, it revolutionized trans-Saharan exchanges. Able to carry heavy loads over long distances without drinking for days, it opened and maintained the continent’s most hostile routes.

More than a beast of burden, the dromedary was a catalyst for commercial expansion—and human tragedy. Its endurance made previously impassable regions traversable, connecting the Muslim worlds of the north to those of Black Africa. Where humans failed, the dromedary triumphed—and with it, the commerce of pain.

The system of the trans-saharan slave trade: logistics of a forgotten crime

Behind the dunes of the Sahara once stretched a dreadfully efficient, well-oiled network, almost invisible to modern eyes: the trans-Saharan slave trade. For more than thirteen centuries, from the 7th to the early 20th century, millions of Africans were torn from their lands and forcibly driven across the desert toward the slave markets of the Maghreb, the Middle East, and sometimes as far as Asia.

Online Movie Streaming Services

The map of this trade is punctuated by routes as ancient as they were deadly:

- Tripoli – Fezzan – Bornu, linking the Mediterranean to the heart of present-day Chad,

- Ghadames – Gao, crossing southern Libya to the Niger River,

- Timbuktu – Algiers, passing through the oases of the Ahaggar and the Saharan fringes,

- Zawila – Darfur, via the Tibesti massifs.

These routes are not merely lines drawn in the sand. They are corridors of pain, where bodies were exhausted, lost, and disappeared. Each stage was marked by fear, humiliation, and hunger. This system was not improvised. It rested on precise relay points, local infrastructures, standardized commercial circuits, embedded in a well-established transnational economy.

Contrary to narratives that seek to reduce this history to a simple foreign invasion, the reality is more complex—and sometimes more cruel. Numerous tribal chiefs, Islamized kings, or vassal states were active links in this human trade. Within kingdoms such as Kanem-Bornu, Wadai, or certain Sahelian emirates, the capture of slaves was an integral part of diplomacy, commerce, and even political identity.

These actors themselves organized raids or purchased captives from other groups to resell them to Arab, Turkish, or Persian traders. It was an economy of exchange: human beings traded for salt, horses, weapons, textiles, or gold. An economy in which the Black human body became a variable currency.

Names with poetic sounds, now almost forgotten, lay at the heart of the system: Kufra, Awjila, Ghat, Agadez, Bilma… These oases functioned as logistical hubs. They were simultaneously caravan gathering points, living warehouses for captives, supply zones, and redistribution centers.

Slaves were sorted there according to their health, age, and sex. The weakest were abandoned; the others were bound in pairs, aligned in columns under the watch of armed guards. For many, this was where the nightmare began. For others, it was already the end.

The figures cited by Arab chroniclers and European explorers are staggering. A single caravan could include several hundred, even thousands, of captives, supervised by dozens of guards and dozens of dromedaries. The journey lasted on average one month, sometimes longer depending on climate and distance.

Mortality was extreme: up to 50% of captives died along the way, victims of thirst, disease, beatings, or simply shot because they could no longer walk. Women were regularly subjected to rape. Children were often castrated to supply the eunuch markets of the Levant. Survivors arrived broken, fragile commodities to be sold in the souks of Tripoli, Algiers, Tunis, or Damascus.

Without the dromedary, this trade would never have reached such scale. Introduced massively into Saharan commerce from the first millennium onward, this animal was a logistical revolution. Capable of carrying heavy loads over hundreds of kilometers without drinking, it became an instrument of horror—and profitability.

Thanks to it, previously impassable routes became reliable trade axes. It made it possible to increase the volume of goods (and thus slaves) transported, shorten travel times, and survive the desert’s relentless aridity. The dromedary was, in short, the biological engine of a large-scale machine of dehumanization.

Demography of erasure: how many? who?

To speak of the trans-Saharan slave trade is first to confront the vertigo of numbers. Across a geographic space as vast as the Sahara and over more than thirteen centuries, there is no single registry, no centralized port of departure, no equivalent of the infamous “Middle Passage.” Yet historians have attempted to estimate the scale of this hidden phenomenon. Among them, Paul Lovejoy, Ronald Segal, and Ralph Austen converge on a chilling range: between 6 and 10 million Africans were torn from their lands and sold across the desert.

These figures do not account for collateral losses: deaths during capture, abandoned children, disintegrated communities. Nor do they count the millions of descendants rendered invisible in host societies, often forced to renounce their identity in order to survive.

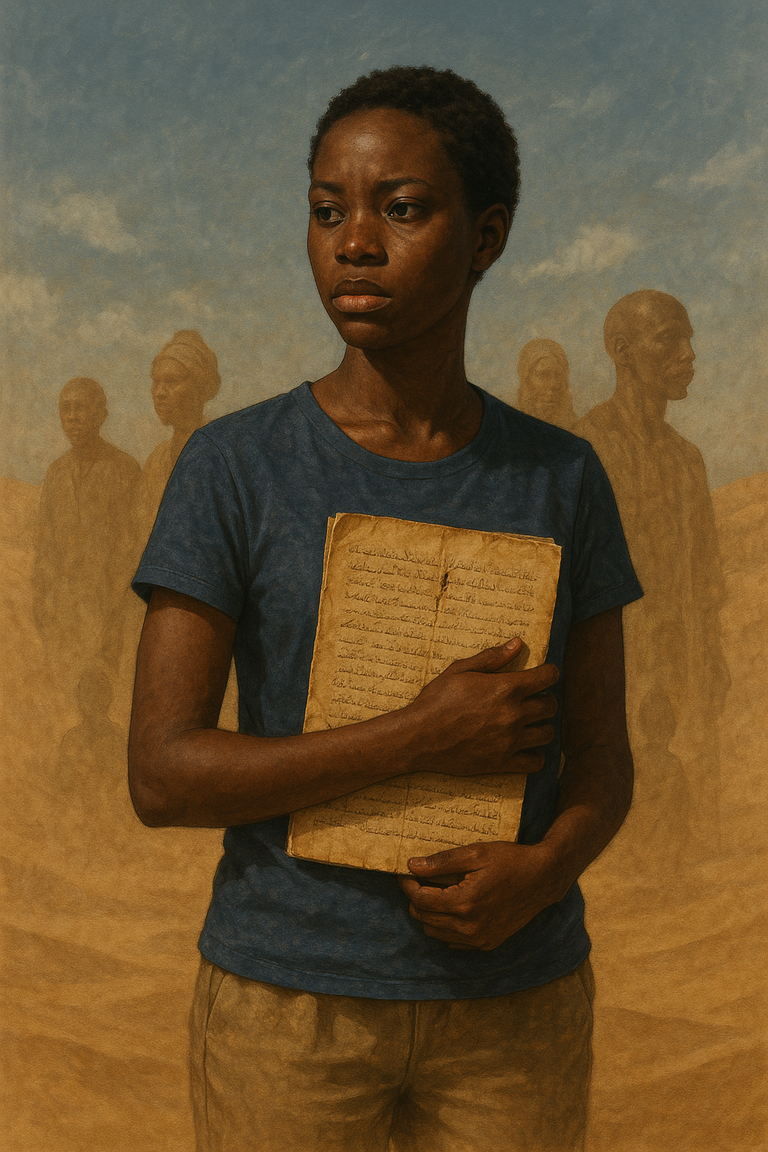

Contrary to a reductive vision that imagines the trans-Saharan slave as merely a robust man destined for physical labor, captives were of all ages, all statuses, and all sexes. Among them were artisans, peasants, chiefs, griots, educated women or healers, and barely weaned children.

But this trade was distinguished by its strong feminization. According to Lovejoy, nearly two-thirds of captives were women. This demographic feature reflects the very nature of the trade: more than agricultural or mining labor (as in the Atlantic world), this was a commerce in bodies, oriented toward domestic service, sexual exploitation, and forced integration into households or harems.

Captured Black women were rarely destined for intensive labor. Their primary assignment lay in private spaces: concubines, servants, nannies, singers, or sexual slaves. They represented both a symbol of prestige for Arab or Turkish elites and a strategic reproductive capital. Some accounts even describe networks specializing in the capture of very young girls, on the grounds that they were more easily “moldable” to their masters’ image.

In the harems of Marrakech, Cairo, or Damascus, the presence of Black women was not uncommon. Their exoticization often came with an ambivalent status: invisible in the public sphere, yet central within the intimacy of families.

Another chilling specificity was the systematic castration of captured Black men. While not all were mutilated, many were—particularly those destined for harems, palaces, or administrative functions, where the master’s trust demanded a symbolic erasure of virility.

This practice, well documented in Arab and European sources, was most often carried out under atrocious conditions, with mortality rates sometimes exceeding 70%. The myth of the “faithful and docile Black eunuch” thus became embedded in the Oriental imagination, as in certain Ottoman or Persian courts, at the cost of dehumanizing mutilation.

These men, both feared and despised, were deprived not only of their freedom but also of their lineage. They embodied a double social death: that of the man and that of the potential father.

Logics and ideologies of trans-saharan slavery

Beyond figures, routes, and accounts of suffering, one must probe the depths of an imaginary constructed to justify the unjustifiable. Like any long-lasting slave enterprise, the trans-Saharan trade relied on a solid ideological architecture, composed of racial stereotypes, religious rationalizations, and hierarchies of civilization. For caravans to cross centuries of desert with chained human beings, minds first had to be convinced that some were made to be dominated.

In the medieval Arab world, sub-Saharan Africans were often designated by the generic term “Zanj.” But this word did not merely denote geographic origin. It became a racial signifier, loaded with demeaning stereotypes.

The treatises of geographers such as Al-Masudi or Ibn Khaldun, and the travel accounts of Ibn Battuta, abound with descriptions that animalize Black populations: instinctive, emotional, lazy, made for servitude. Some Arab poets even compared their dark skin to that of the devil, turning blackness into a spiritual vice. The Zanj thus became the absolute Other—not only foreign, but ontologically inferior.

In collective memory, this figure of the inferior Black person fed a perverse exoticization. Black women became objects of fantasized desire; Black men (when not eunuchs) were reduced to brute force. This vision persisted into Ottoman and Persian courts, and traces of it still linger today in some North African and Middle Eastern societies.

At the theological foundation of this racial hierarchy lies the biblical and Qur’anic narrative of the Curse of Ham, often interpreted in racialized terms. According to this reading, Ham, son of Noah, was cursed for seeing his father’s nakedness. His descendants (identified with Black Africans) thus bore a curse justifying their servitude.

This interpretation was neither universal nor orthodox, but it was instrumentalized for slaveholding purposes. In certain medieval Muslim legal commentaries, Black skin became the visible sign of natural inferiority, even divine punishment.

Moreover, although Islam strictly forbids enslaving a fellow Muslim, this distinction was frequently circumvented. In theory, only kafir (pagans or animists) could be enslaved. In practice, Black Muslims were captured, sold, and silenced, their conversions denied or ignored. Religious belonging became secondary to skin color.

The trans-Saharan trade was not solely the work of isolated merchants or raiders. It was also institutionalized through political agreements between Islamized African states and Arab or Berber empires. The most famous is the Baqt Treaty, signed in the 7th century between the Christian kingdom of Makuria (Nubia) and Muslim Egypt. This treaty stipulated that the Nubians were to supply 360 slaves per year to Cairo in exchange for peace and access to trade.

Other informal agreements followed, between the kingdoms of Kanem-Bornu, Mali, Songhai, or Darfur and northern powers. These treaties, sometimes called “blood pacts,” organized large-scale trade in which captives became political currency, not merely war enemies.

The official distinction between “pagan Black slave” and “free Muslim brother” was thus fragile and porous. Whenever profit was at stake, religious principles bent to economic logic. Conversions were retroactively ignored, forgotten, or denied; biased readings of sacred texts were used to justify the unjustifiable.

Thus, century after century, an ideology of contempt toward sub-Saharan Africans was constructed in parts of the Arab world—an ideology that did not vanish with the formal end of the trade and continues to haunt social relations, media representations, and even everyday interactions in certain regions.

Social, cultural, and geopolitical consequences of the trans-saharan slave trade

The trans-Saharan slave trade did not merely uproot millions of human lives from African lands. It left deep scars, still visible today in social structures, mental representations, and geopolitical tensions between sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab world. This centuries-old commerce, often obscured, shaped worlds and mentalities. It disrupted African societies as much as it enriched economies north of the desert.

In the long term, the demographic effects of the trans-Saharan trade are comparable to those of the transatlantic trade. Between 6 and 10 million Africans were torn from their lands, with excess mortality often estimated at over 30% during the journey. This human hemorrhage durably weakened entire regions, caused the collapse of certain communities, and fueled cycles of violence over centuries.

Entire areas, particularly in the eastern and central Sahel, were drained of their youth, deprived of labor, and exposed to constant raids. Populations withdrew, fortified themselves, and fragmented. Chronic insecurity reshaped settlement patterns, power structures, and economic dynamics for generations.

Among the most enduring social legacies is the formation of hereditary slave castes in many Saharan and Sahelian societies. The Haratin in Mauritania, the Bellah in Mali and Niger, or the Tebu in Chad and Libya are direct descendants of trans-Saharan captives, long regarded as inferior by birth, even after the official abolition of slavery.

In several countries, these groups remain stigmatized and marginalized, sometimes treated as second-class citizens. In Mauritania, for instance, hereditary slavery was formally abolished only in 1981, criminalized in 2007, and reinforced in 2015—evidence of the deep resistance of a system embedded in social structures and mentalities.

The trans-Saharan trade profoundly shaped perceptions of skin color in North African and Middle Eastern societies. Blackness remained associated with servitude, inferiority, and domesticity. Over centuries, a racialized hierarchy emerged, valorizing light skin and stigmatizing dark skin.

This structural racism, inherited from an ancient slave system, continues to manifest in media, unspoken laws, and social practices. Black populations in Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Lebanon, or Saudi Arabia are still regularly subjected to phenotype-based discrimination—a direct legacy of the trade, rarely acknowledged or debated publicly.

Contrary to a simplistic view of slavery as mere agricultural labor, the trans-Saharan trade fueled all layers of precolonial and colonial economies in the Arab world. African captives were used in the salt mines of Taghaza and Taoudeni, oasis plantations, bourgeois households, and also in armies.

Entire regiments, such as the famous Mamluks or the Black Guards of Moroccan sultans, were composed of Black slaves, often castrated. In some cities, elites employed hundreds of captives as servants, artisans, or builders. The slave economy was not marginal; it was central to the prosperity of several states.

Finally, the trans-Saharan trade deepened a memory gap between Black Africa and the Arab world. This shared past, marked by domination and exploitation, is rarely acknowledged, scarcely taught, and often repressed. Today, it fuels diplomatic tensions, identity resentments, and unease in South–South relations.

The rise of pan-African movements, the rediscovery of suppressed memories, and denunciations of anti-Black racism in the Maghreb or the Middle East all signal a demand for historical recognition. For without truth about the past, it is difficult to build authentic fraternity in the present.

Slow abolition and its resistances

If trans-Saharan slavery is little present in textbooks and collective memory, it is partly because its abolition was late, incomplete, and often circumvented. Far from solemn proclamations and symbolic dates, abolition was a slow, fragmented, and politically ambiguous process, stretching over more than a century and a half, with resurgences continuing to this day.

Contrary to the widespread belief that the Muslim world quickly banned slavery, historical facts tell a very different story. Tunisia is often cited as a pioneer, with official abolition as early as 1846 under Ahmed I Bey—preceding France (1848) and the United States (1865). Yet this isolated initiative did not reflect a regional trend.

In most North African and Sahelian territories, slavery persisted well beyond the 19th century. In Saudi Arabia, it was officially abolished only in 1962. But Mauritania crystallizes all contradictions: abolition was formally declared only in 1981, then criminalized in 2007, and reinforced in 2015—proof of the silent resistance of a system deeply rooted in social structures and mentalities.

Resistance to abolition did not always take the form of armed opposition. In many cases, it was inaction, administrative hypocrisy, or silence that allowed slavery to persist in other forms. In several countries, laws were adopted under external pressure but rarely enforced on the ground. Freed slaves had no land, no civil rights, and no support structures, condemning them to economic dependence that prolonged submission.

Reports by the UN and NGOs such as Anti-Slavery International still document cases of slavery by descent today, notably in Mauritania, Mali, or Libya. In societies where oral tradition and custom outweigh legal texts, the racial hierarchy inherited from the trans-Saharan trade continues to structure social order.

European colonial powers, notably France and the United Kingdom, played a paradoxical role. On one hand, they imposed abolitionist decrees in their North African and Sahelian colonies, often under the banner of a “civilizing mission.” On the other, they benefited from existing slave structures to consolidate authority and supply labor.

In Sudan, Niger, Algeria, or French West Africa, colonial administrators often turned a blind eye to servile practices, or even implicitly encouraged them. After official abolition, colonizers frequently replaced slavery with forced labor systems or economic exploitation just as destructive—as evidenced by indigénat policies, corvée labor, and extractive regimes.

Far from being a closed chapter, trans-Saharan slavery still leaves visible scars in contemporary societies. Migration crises have reactivated ancient circuits of domination. In Libya, after the fall of Gaddafi, mafia networks reestablished brutal human trafficking, sometimes in plain sight. Sub-Saharan migrants are sold as slaves, imprisoned, beaten, and sexually exploited, in a horrifying echo of ancient caravans.

These contemporary practices, though illegal, thrive on repressed memory, historical impunity, and persistent structural racism. They raise questions about international inaction and the silence of the states concerned.

Why does the trans-saharan slave trade still disturb?

Despite spanning nearly thirteen centuries and shattering millions of lives, the trans-Saharan slave trade remains one of the most invisibilized chapters of world history. Not due to lack of documentation—testimonies, travel accounts, and scholarly works exist—but because of a thick wall of taboos, diplomatic silences, and identity discomforts.

Unlike the transatlantic trade, denounced through centuries of abolitionist struggle and carried by a strong memorial movement in the Americas, the trans-Saharan trade is rarely confronted by a collective, let alone institutional, voice. On one side, it implicates African Muslim actors (Sahelian kingdom chiefs, Berber traders, Islamized sultanates) in active and sometimes central roles. On the other, it involves societies still predominantly Muslim today—such as Morocco, Tunisia, Mauritania, or Saudi Arabia—in a slave system that persisted well beyond the 19th century.

To evoke this reality is to unsettle deeply rooted identity narratives. It is easier to see oneself as colonized than as enslaver. More comforting to denounce the West than to confront one’s own historical responsibilities. This moral discomfort is amplified by the fact that mental and social structures inherited from the trade—racial hierarchies, contempt for Blackness, hereditary castes—still persist in some countries.

In public discourse, the trans-Saharan trade becomes a slippery terrain of memory warfare. For some authoritarian or religious regimes, any mention is perceived as an “unnecessary divider,” a “Western plot,” or an attempt to indict Islam itself. Conversely, it is sometimes instrumentalized by anti-Muslim or radical pan-African currents to portray “the Arab” as the historical enemy of Black Africa, in an essentialist and dangerously reductive logic.

This political game of silence or escalation prevents any calm, shared work of memory. Positions harden: some in denial, others in accusation. And in between, historical victims, their descendants, and societies inheriting this history are deprived of recognition and repair.

Unlike the Atlantic trade—which has major memorial sites (Gorée, Ouidah, Nantes), official commemorations (May 10 in France, August 23 at UNESCO), and a widely taught narrative—the trans-Saharan trade remains a vacant field.

There is no international day of commemoration dedicated specifically to it. School textbooks in concerned countries barely mention it, often in sanitized form. There is no major museum in Tripoli, Timbuktu, or Cairo devoted to this history. The voices of Black slaves victimized by this trade are absent from public space, cinema, and mainstream literature.

This memorial void fuels structural forgetting, preventing not only symbolic repair but also the deconstruction of inherited racial hierarchies. Without recognition, wounds remain open. Without commemoration, trauma is silenced. Without narrative, history is confiscated.

Repairing forgetting for an integral memory

As long as Africa does not tell all of its history, it will continue to walk on one leg. Forgetting is never neutral: it shapes narratives, orients consciousness, and distorts struggles. In the case of the trans-Saharan slave trade, forgetting is not mere omission; it is a memorial amputation, a fracture still alive in the body of Black consciousness.

The struggle for recognition of Atlantic slavery (from Gorée to Haiti, from the Code Noir to Toussaint Louverture) enabled the slow emergence of shared memory in affected countries. Books, school programs, and commemorations were established, notably under the influence of figures such as Aimé Césaire, Maryse Condé, and Christiane Taubira.

But what about the trans-Saharan slave trade?

Few African or Afro-descendant students know that millions of men, women, and children crossed the Sahara, sold in Tripoli, Cairo, Mecca, or Muscat. Few know that this history extended into the 20th century, long after the official abolition of the triangular trade. Worse still, in some regions, descendants of slaves still live in conditions of social subjugation.

It is therefore imperative to integrate this chapter into history textbooks from primary school onward—not as a footnote, but as a central chapter of African and world history. Teaching slavery in Africa is not tarnishing memory; it is restoring truth.

The memory of slavery is also that of resistance, often erased by narratives of suffering. Yet even at the heart of the trans-Saharan trade, voices rose, revolts erupted, paths to emancipation were forged.

Consider Bilāl ibn Rabāh, a freed Black slave who became Islam’s first muezzin and a close companion of the Prophet Muhammad. His ascent was both spiritual and political, symbolizing an original Islam that affirmed equality among believers—far removed from later slave practices of many Muslim states.

Consider also the Zanj Revolt, a major uprising in the 9th century in present-day Iraq, led by Black slaves from East Africa subjected to inhumane conditions on sugar plantations. For fifteen years, these men resisted, organized an army, built a fortified city, and challenged Abbasid power. An episode too little known, despite being one of the earliest slave revolts in world history.

It is time to honor these figures, inscribe them into collective memory, and pass them on to new generations.

Repair requires action. Here are some paths toward an integral and reparative memory:

- Establish a day of commemoration for the trans-Saharan slave trade, in coordination with the African Union and cultural organizations of the Maghreb and Middle East.

- Create sites of memory in Tripoli, Timbuktu, Agadez, Algiers, or Mecca, to materialize routes of suffering and celebrate forgotten resistances.

- Launch South–South research and academic cooperation programs between historians of sub-Saharan Africa, the Maghreb, and Gulf countries.

- Support the production of cultural works (films, comics, series, podcasts, exhibitions) to make trans-Saharan history visible in the collective imagination, on par with the Atlantic trade.

- Encourage citizen speech, testimonies from Afro-Arab communities, and local initiatives against discrimination inherited from slavery.

For it is not enough to denounce slavery of the past; we must also fight its ghosts today: anti-Black racism in the Maghreb, discrimination against the Haratin in Mauritania, modern slave markets in Libya, color hierarchies in post-slavery societies.

The desert does not erase chains

Silence does not heal. It buries. It corrodes. And in the case of the trans-Saharan slave trade, it has built around pain a wall of sand, taboos, and forgetting. Yet beneath every Sahara dune, beneath every ancient oasis stone, beneath every silenced memory, lie echoes of a history never fully told.

Africa cannot conceive itself as free if it refuses to confront all its pasts—the most painful as well as the most repressed. The triangular trade left deep scars. But it was not alone. The trans-Saharan slave trade also shattered millions of lives, and its imprint remains visible in gazes, hierarchies, and silences.

Restoring this memory is not about division. It is about unity. It is about rejecting selective memories, truncated narratives, and one-sided commemorations. It is about building a common foundation upon which a sincere pan-African unity can finally rise—one that does not flee its shadows, but illuminates them.

For a partial memory cannot sustain a total project. And as long as the desert continues to cover the chains, Africa will walk with a past that weighs it down instead of lifting it up.

Sources

Tidiane N’Diaye, The Veiled Genocide, Gallimard, 2008

Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa, Cambridge University Press, 2011 (3rd ed.)

Sean Stilwell, Slavery and Slaving in African History, Cambridge University Press, 2014

Bernard Lugan, History of North Africa, Ellipses, 2000

John Ralph Willis (ed.), Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa, Vol. I & II, Routledge, 1985

Ibn Battuta, Travels (trans. C. Defrémery & B.R. Sanguinetti, La Découverte, 2005)

Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddima (trans. Vincent Monteil, Sindbad, 2002)

Al-Maqrizi, Chronicles of Egypt (14th century)

Claude Meillassoux, Anthropology of Slavery, PUF, 199…

Ali A. Mazrui, “The Black Experience in the Arab World,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, 1975

Global Slavery Index Report, Modern Slavery: A Global Estimate, Walk Free Foundation, 2022

Table of contents

Selective Memory

The Ancient Origins of an Economy of Capture

The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade System

The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade System: Logistics of a Forgotten Crime

Demography of Erasure: How Many? Who?

Logics and Ideologies of Trans-Saharan Slavery

Social, Cultural, and Geopolitical Consequences of the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade

Slow Abolition and Its Resistances

Why Does the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade Still Disturb?

Repairing Forgetting for an Integral Memory

The Desert Does Not Erase Chains

Sources