From the shadow of the Panthers to armed “expropriations,” the Black Liberation Army waged a clandestine war against the American state throughout the 1970s. As one of its figures, Assata Shakur, passes away, this article looks back at the origins, operations, repression, and contested legacy of this underground organization.

Assata is dead, the BLA returns

On September 25, 2025, Assata Shakur died in Havana, far from cameras and media frenzy. She was seventy-eight. For Washington, there was official silence; for Cuba, a terse communiqué. Yet behind this discreet death, an entire chapter of the history of Black struggles in America resurfaces. For Assata was not merely an activist in exile. She was the last living incarnation of the Black Liberation Army, that clandestine organization born from the ashes of the Panthers and which, in the 1970s, chose the path of armed struggle against the American state.

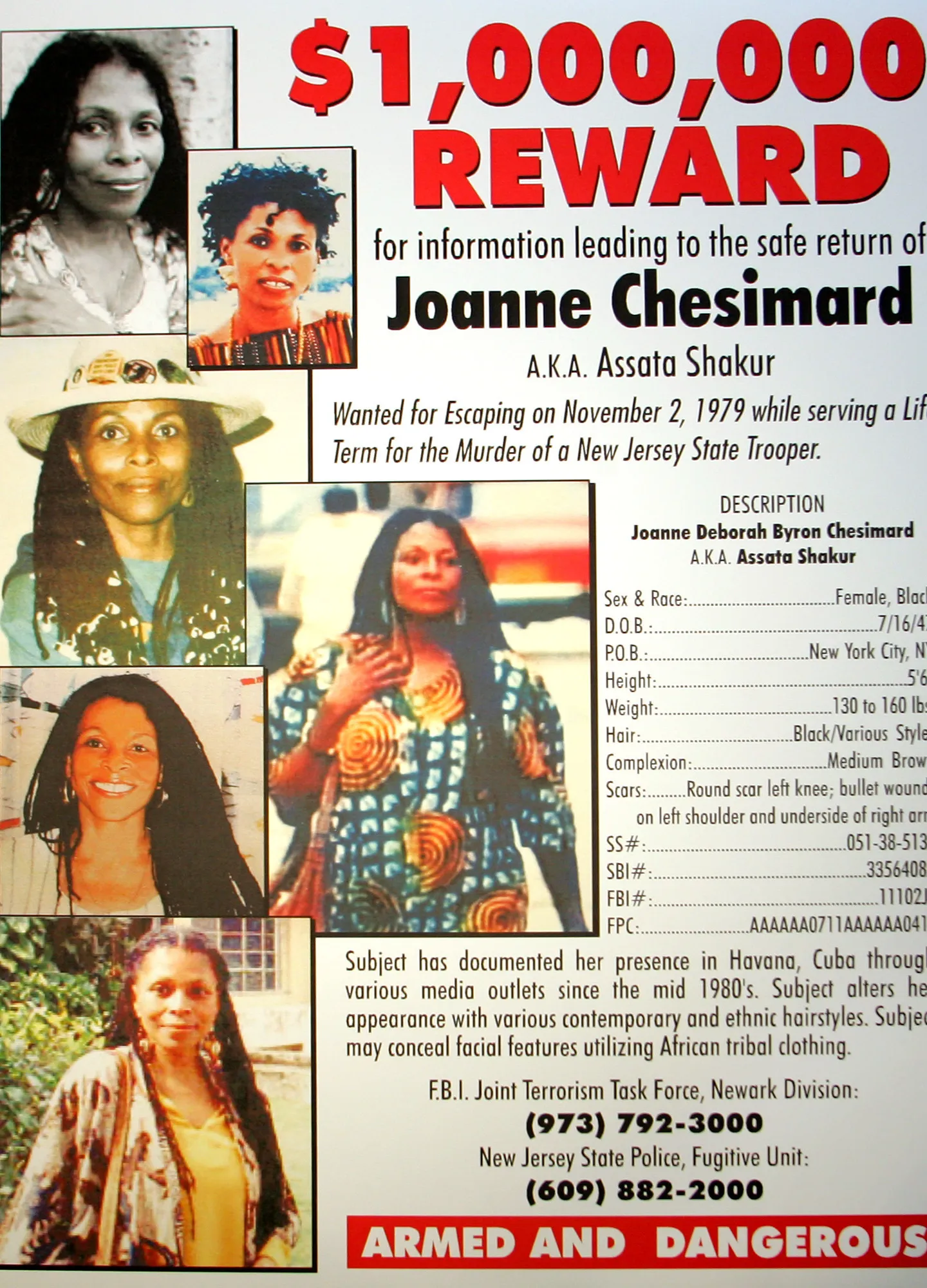

With her passing, memory resurfaces. FBI wanted posters bearing her face among the most wanted criminals circulate again on social media. Slogans once chanted in the streets of Harlem and on New York campuses reappear on placards: Free Assata, Hands off the Panthers. In Black neighborhoods and pan-African circles, her name still evokes a promise of rupture; for others, a wound that never healed.

Understanding the BLA does not mean reducing it to the convenient cliché of a band of outlaws. Nor does it mean elevating it to a simple romantic avant-garde. It means grasping the complexity of a movement nourished by Third World revolutions and shaped by the structural violence of post-segregation America. The history of the Black Liberation Army is made of ideology and clandestinity, robberies and trials, betrayals and myths. And if Assata’s death marks the end of a body, it reopens a file the United States has never truly closed: that of its internal war against radical Black insubordination.

Genealogy of a Black guerrilla

The Black Liberation Army did not emerge from nowhere, as a sudden outgrowth of urban violence. It fits into a long lineage in which the community self-defense of Black ghettos in the 1960s gradually turned into clandestine armed struggle. At the origin was first the simple, almost banal gesture of protecting one’s neighborhood from the police. This was the doctrine of the Black Panthers, inherited from the patrols of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland: monitor the police, prevent abuses, oppose the white rifle with the Black rifle. But very quickly, this defensive logic slipped into another grammar—that of the offensive.

The Republic of New Afrika, an organization advocating the creation of an independent Black state in the South, had already laid the foundations of a secessionist imagination. The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), under the influence of Robert F. Williams, went even further. Williams, exiled to Cuba and then China, popularized the idea that racial equality would never be won at the ballot box, but through guerrilla warfare. Through his writings, relayed by activists such as James and Grace Lee Boggs in Detroit, a simple doctrine spread: the liberation of Black Americans could not be separated from the anti-colonial struggles of the Third World.

This vision gained traction among young Panthers. But as the FBI multiplied infiltrations and provocations through the COINTELPRO program, the Black Panther Party split. The California wing, under Newton, favored social programs and media visibility, while the New York branch, around Geronimo Pratt and more radical militants, leaned toward clandestinity. Repression—mass arrests, targeted assassinations, disinformation campaigns—deepened this rift. It was in this climate of suspicion and fragmentation that the Black Liberation Army emerged.

The transition was clear: from the visible and legal community militia to the invisible, compartmentalized, clandestine cell. Self-defense became offensive combat, and the enemy was no longer merely neighborhood police, but the federal state itself. Militants no longer patrolled streets; they hid in safe houses, planned robberies and ambushes, and conceived the struggle not as an episode, but as a permanent condition. The BLA was therefore not an absolute rupture: it was the illegitimate, radicalized, and clandestine child of Pantherism and Black dreams of sovereignty.

Identity card of the BLA

The Black Liberation Army officially appeared in 1970, in the wake of internal divisions within the Black Panther Party. It survived only a decade, until 1981, but its actions and the imaginary it generated were enough to leave a lasting mark on the history of Black protest. Its ideological line lay at the intersection of Marxism-Leninism and Black nationalism, two traditions its militants deemed inseparable: capitalism was seen as the material framework of racism, and Black emancipation as one stage of a global revolution against imperialism.

In the political cartography of the time, the BLA positioned itself clearly on the far left—but an armed left, convinced that electoral or associative paths led only to dead ends. Its objective was explicit and unambiguous: to take up arms for the liberation and self-determination of Black people in the United States.

Unlike the Panthers, who developed a structured and media-visible national organization, the BLA opted for a clandestine architecture. No central committee, no visible hierarchy, but a network of autonomous cells operating by affinity and according to the “need to know” principle. This decentralization, inherited from Third World guerrillas, aimed to reduce vulnerability to police infiltration. In the mid-1970s, an attempt at coordination—the BLA Coordinating Committee, via a manifesto titled Call to Consolidate—sought to unify these scattered nuclei. But this embryonic structure never moved beyond draft form, as clandestinity and repression made any durable centralization illusory.

The BLA’s repertoire of action illustrated this logic of underground war. Its members spoke of “expropriations” rather than robberies, arguing that they were reclaiming from the capitalist system the means to finance the revolution. These actions were joined by targeted attacks on police, considered the primary occupying force in Black neighborhoods; acts of sabotage with explosives; attempts to free political prisoners; kidnappings; and even a plane hijacking to Algeria in 1972, intended to draw international attention to their cause.

In these tactical choices lay the conviction that the struggle had to be global: it was not only about confronting police in the streets of Harlem or Newark, but about linking Black American revolt to guerrillas in Africa, Asia, and Latin America who were standing up to empires. For ten years, the BLA embodied this ambition: to transform the ghetto into a front, and racial oppression into a revolutionary battlefield.

A red and black decade

Between 1970 and 1981, the Black Liberation Army waged what it called a war of liberation, but what the federal state labeled domestic terrorism. This decade reads as a succession of bloody episodes, clandestine operations, spectacular trials, and judicial controversies.

1970–1972: the escalation

From its earliest steps, the BLA chose direct confrontation. In San Francisco in 1970, a bomb exploded in St. Brendan’s Church during a police officer’s funeral—a symbol of an America under siege. Few were injured, but the psychological impact was immense: urban guerrilla warfare was no longer a hypothesis; it was here. In New York and Atlanta, attacks on law enforcement multiplied.

The year 1971 marked a turning point with the assassination of officers Joseph Piagentini and Waverly Jones in Harlem, followed in 1972 by that of troopers Gregory Foster and Rocco Laurie. These cold-blooded executions carried out in broad daylight sent shockwaves. But the justice system faced a persistent difficulty: evidence was lacking, testimonies crumbled, and many cases rested on fragile investigations, sometimes tainted by coerced confessions or procedural inconsistencies.

1972–1979: internationalization and clandestinity

The BLA now sought to go beyond the American framework. In November 1972, militants hijacked Delta Flight 841 bound for Miami and forced the crew to land in Algeria, a country then actively supporting revolutionary movements. Ransoms were seized, but the operation consecrated the BLA’s entry into transatlantic Third Worldist networks. A few months later, in May 1973, the shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike claimed the life of trooper Werner Foerster and sealed the fate of Assata Shakur and Sundiata Acoli.

More than a clash, it was a crystallization: the media seized on the case, and the federal state turned it into a symbol. Assata, wounded, became the most wanted woman in America, soon elevated to the rank of absolute internal enemy. The cycle closed in 1979, when she escaped spectacularly from prison with the combined support of the BLA and allies from the white radical left grouped in the May 19th Communist Organization. The image of Assata vanishing into clandestinity became an urban legend, fed by the silence of her supporters.

1981: apogee and fall

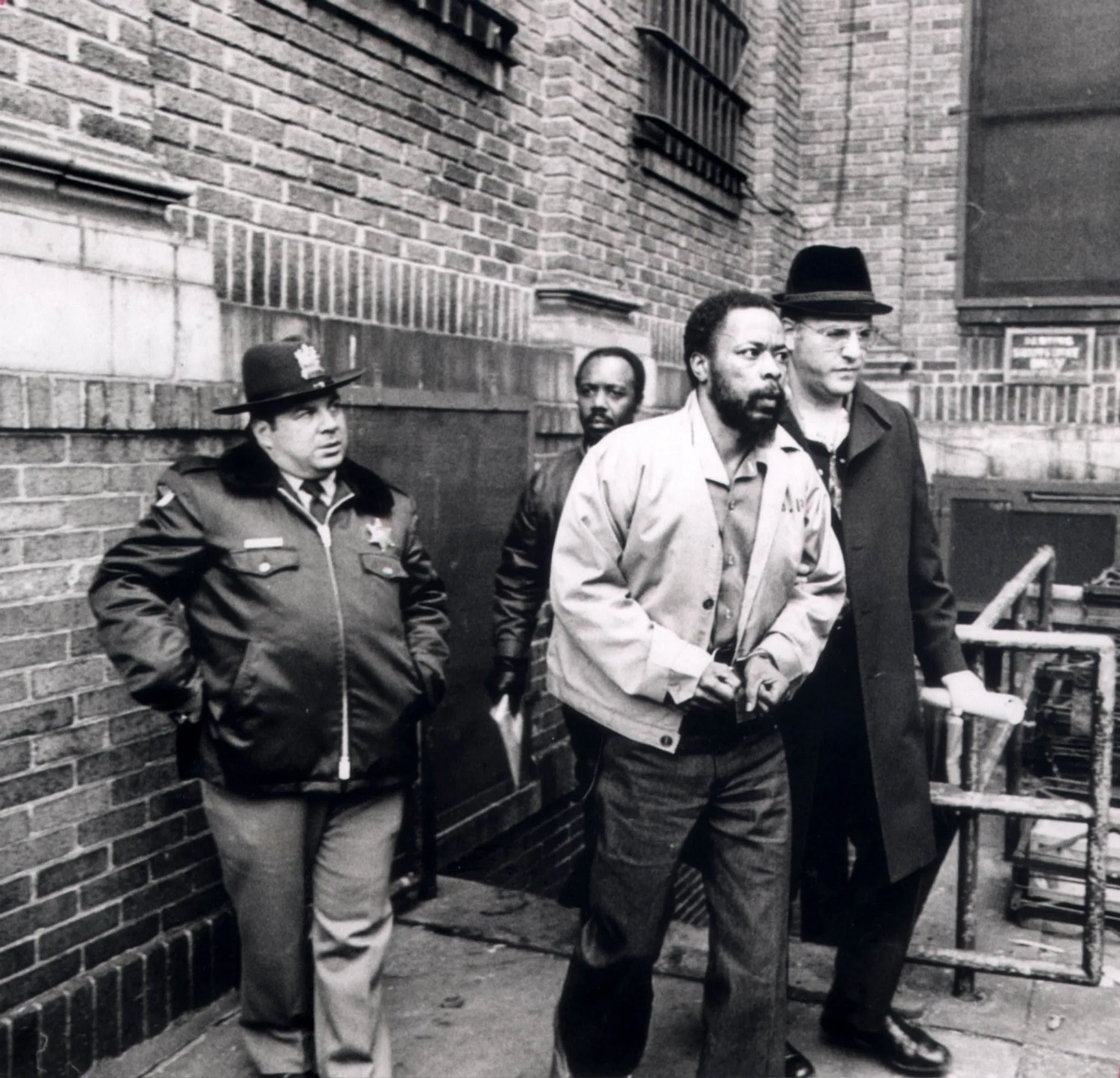

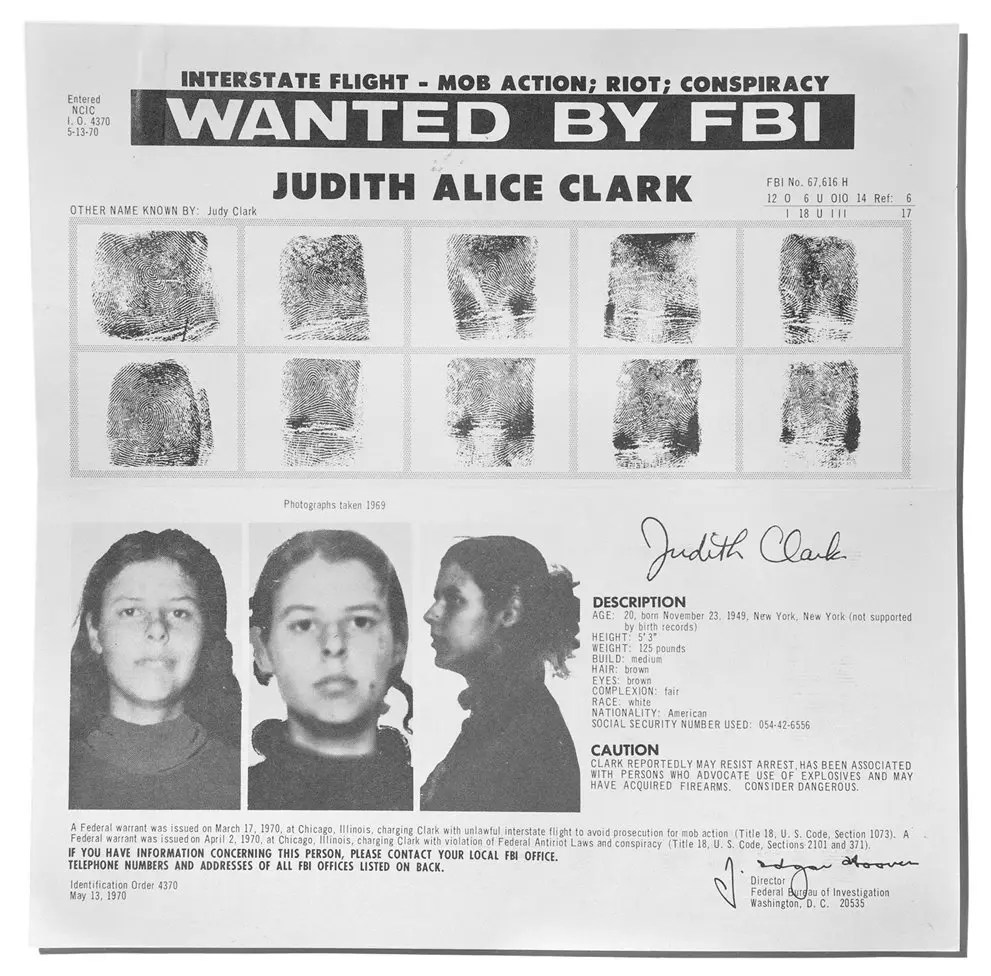

On October 20, 1981, the BLA attempted a spectacular operation that turned into disaster: the Brink’s armored truck robbery in Nanuet and Nyack, New York. The operation was carried out with the help of former Weather Underground members, including Kathy Boudin, David Gilbert, and Judith Clark. The loot was meant to finance the revolution, but the ensuing shootout left three dead: two police officers and a guard. This attack marked the beginning of the end. Arrests poured in, networks were dismantled, trials followed. For the FBI and the federal government, it was the victory of a methodical counterinsurgency. For militants, it was the price paid in a war they knew was unequal.

In eleven years, the BLA was at once invisible and omnipresent, hunted and fantasized, feared and misunderstood. Its trajectory ended in blood and bars, but its memory would continue to haunt the Black American imagination.

Doctrine and internal debates

Though the Black Liberation Army was a clandestine organization, it was never merely an accumulation of weapons and robberies. Behind the rifles were texts, thought, and an attempt to give ideological coherence to what might otherwise have appeared as raw violence. BLA communiqués, written and circulated fragmentarily in the 1970s, reveal a theoretical matrix: anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and—more rarely for such movements—anti-sexist.

The originality of the BLA lay in linking class struggle to the Black American condition. For its militants, ghetto poverty, the criminalization of Black youth, and police brutality were not anomalies; they were the naked expression of racial capitalism. Social revolution could not be conceived without racial liberation, and vice versa. Hence this conviction: the struggle of Blacks in the United States was only a particular front of a global war against imperialism.

In 1976, the manifesto of the BLA Coordinating Committee, titled Call to Consolidate, pushed this reflection further. It contained a bold line: a call for tactical unity with white revolutionaries, notably those from radical milieus such as the Weather Underground. The goal was pragmatic: to multiply logistical, financial, and media support, without ever dissolving the Black centrality of the struggle. This opening sparked internal debates: some saw it as a necessary expansion, others feared dilution or even co-optation.

These tensions overlapped with other fractures. Should mass action—demonstrations and social work—be prioritized, at the risk of falling back into the Panthers’ wake? Or should pure armed clandestinity be maintained, even at the cost of isolating the movement from its popular base? Should the organization be centralized, establishing a hierarchy, or should the radical autonomy of cells be preserved—guaranteeing security but fostering fragmentation?

Relations with other Black organizations were equally ambivalent. With the Black Panther Party, relations were initially fraternal, then stormy: Panthers reproached the BLA for precipitating confrontation and marginalizing the cause by tipping too quickly into violence. The BLA, in turn, accused the BPP of yielding to reformism and becoming vulnerable to infiltration. With the Republic of New Afrika (PG-RNA), which advocated secession and the creation of a Black state in the South, ties were cordial but distant: the two visions shared a horizon but diverged in method.

These debates, never resolved, partly explain the BLA’s trajectory: an organization perpetually torn between poles—internationalist ideology and clandestine survival, calls for unity and visceral mistrust. A guerrilla doomed to instability, yet coherent in its deeper aim: to make American ghettos a front of the global revolution.

Police, FBI, and counterinsurgency

From its birth, the Black Liberation Army was in the FBI’s sights. The organization embodied what J. Edgar Hoover, then all-powerful director of the agency, considered the absolute internal enemy: a Black, Marxist, internationalist guerrilla that rejected political compromise and embraced violence. The government’s methods were commensurate with this fear: infiltrations, disinformation campaigns, provocations, and targeted dismantling.

The COINTELPRO program, initially designed to neutralize communists, had already been used against Martin Luther King Jr. and then the Panthers. It found in the BLA an ideal target. Infiltrated agents fueled splits, pitted militants against one another, and organized traps. The state exploited the BLA’s clandestinity itself: by amplifying internal paranoia and making any centralization impossible, it turned each cell into an isolated target.

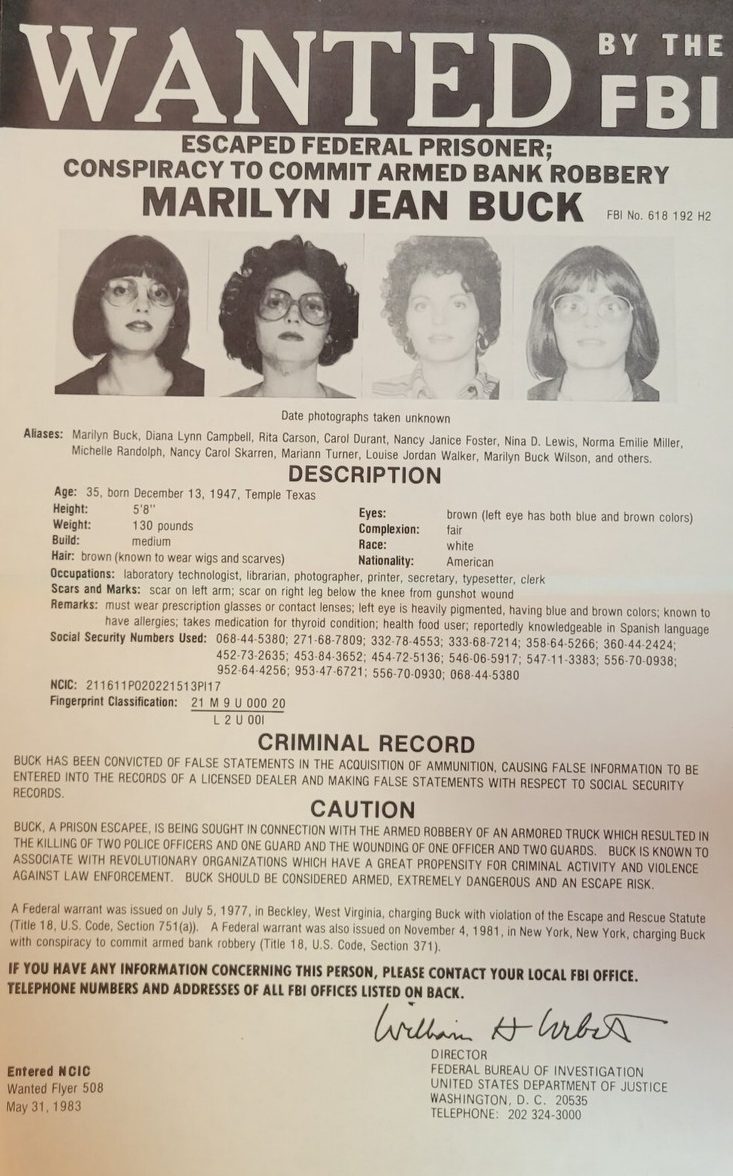

From 1972 onward, the FBI set up joint mechanisms with local police—the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF), a prefiguration of modern “counterterrorism.” The Bureau’s wanted posters, plastered in train stations and disseminated in the press, were part of this strategy: they served not only to capture, but to manufacture the enemy. The faces of Assata Shakur, Sundiata Acoli, or Mutulu Shakur circulated nationwide as public enemies, on par with common criminals.

Even numbers were instrumentalized. Between 1970 and 1976, the FBI attributed more than seventy armed incidents to the BLA. The Fraternal Order of Police claimed that thirteen officers had been killed by its members. But behind these figures, reality remains uncertain. Some cases never led to convictions for lack of evidence. In others, ordinary criminal acts were attributed to the BLA to amplify the threat. The line between guerrilla and criminality was deliberately blurred as a tool of psychological warfare.

Thus, the American counterinsurgency against the BLA was not limited to arrest and incarceration. It was also a narrative battle, in which the state imposed the word “terrorist” to delegitimize any notion of armed Black resistance. In this war of images, the BLA lost the media battle before it lost on the ground.

Dramatis personae

The Black Liberation Army was not an army in the classical sense. It had neither a general staff nor a centralized command. But it had faces, trajectories, and often shattered destinies that together draw the human map of an urban guerrilla.

Assata Shakur remains the most emblematic figure. A former Panther, she went underground with the BLA in the early 1970s. Her life changed on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973: wounded and arrested after the death of trooper Werner Foerster, she became Public Enemy No. 1.

Convicted despite fragile evidence and incarcerated under conditions denounced as inhumane, she escaped in 1979 with the help of the BLA network and the May 19th Communist Organization. Her exile in Cuba made her a geopolitical symbol, a dissident protected by Castro and sought by Washington. In 2013, she became the first woman placed on the FBI’s “Most Wanted Terrorists” list, proof that her mere existence continued to haunt the American state.

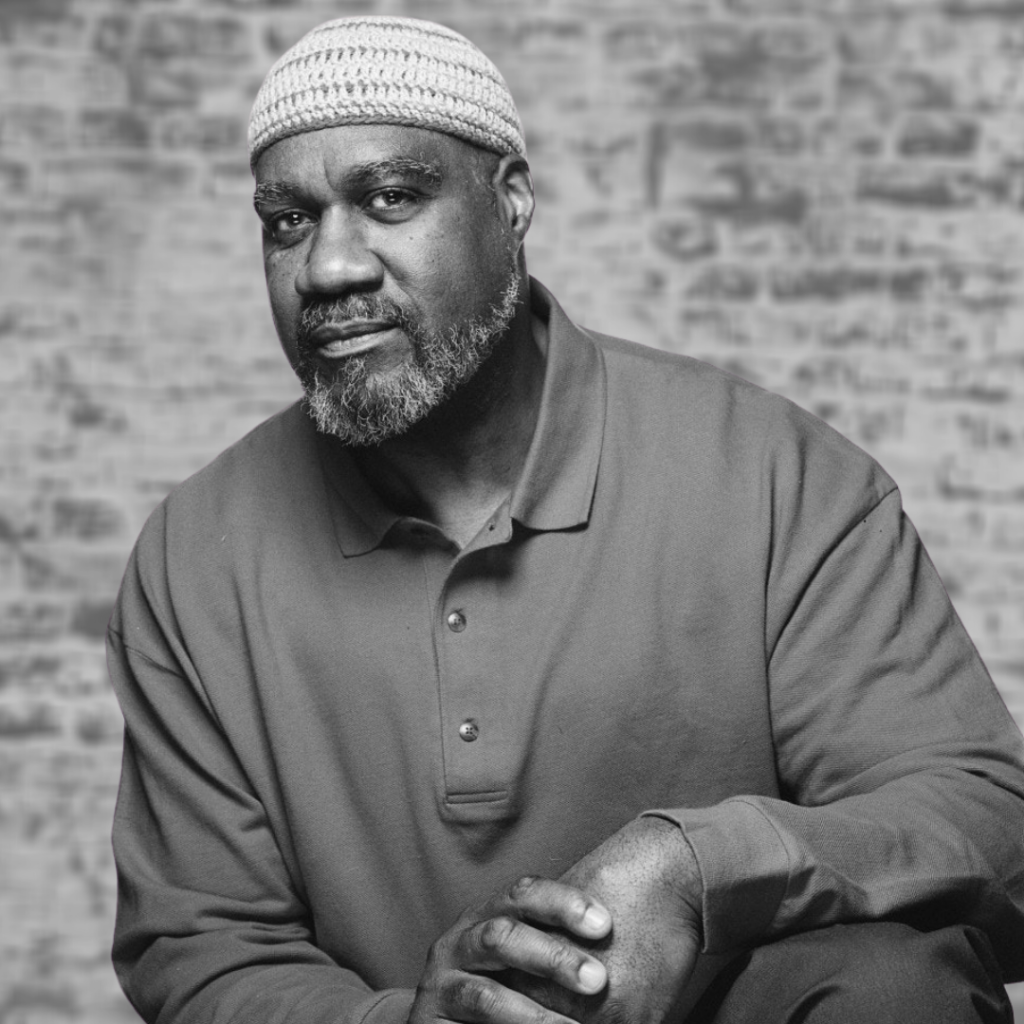

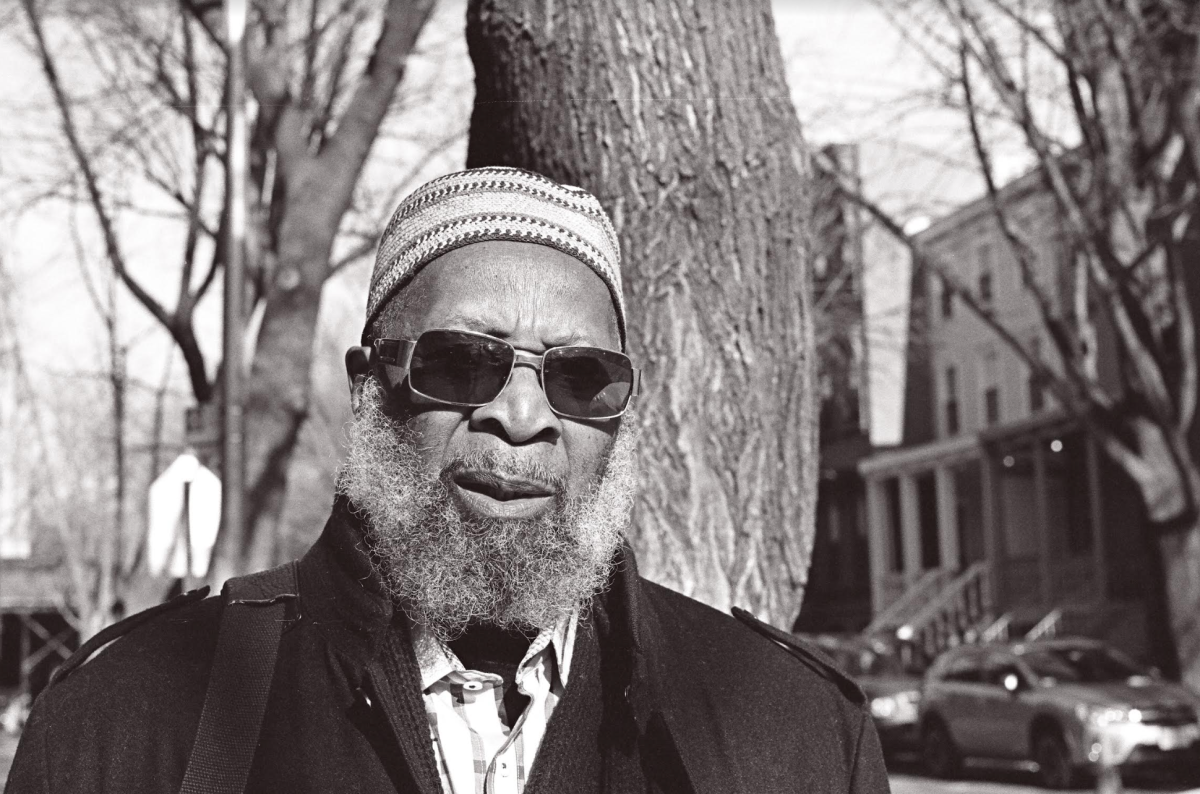

Alongside her stood Sundiata Acoli, arrested in the same Turnpike shootout. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he became one of the longest-held political prisoners in the United States, incarcerated for nearly half a century. In 2022, after multiple parole denials, he was finally released—aged, ill, but standing—a living memory of a forgotten war.

Mutulu Shakur, stepfather of rapper Tupac, was a key strategist. A committed acupuncturist, he participated in Assata’s escape and the 1981 Brink’s robbery. Arrested in 1986, he received a heavy sentence. He died in 2023, released on humanitarian grounds after a terminal cancer diagnosis. His passing marked the end of a generation of fighters who remained faithful to the cause to the end.

There were also Kuwasi Balagoon, poet and militant, who died of AIDS in prison in 1986; Herman Bell and Jalil Muntaqim, convicted for the 1971 killing of officers Piagentini and Jones in Harlem, released after more than forty years behind bars; Sekou Odinga, captured in 1981 and imprisoned for thirty-three years before regaining freedom in 2014.

Among white allies, Marilyn Buck, a radical activist who supported the BLA and participated in Assata’s escape, remains an ambiguous figure. She died of cancer in 2010 shortly after her release. Judith Clark, involved in the Brink’s robbery and incarcerated for nearly four decades, was pardoned in 2019 by the governor of New York.

These destinies share a common trait: all paid a heavy price—life imprisonment, exile, or death. In militant memory, they remain the “fallen or imprisoned soldiers of an unrecognized war.” For the state, they were terrorists. For their supporters, prisoners of war. Between these narratives, truth continues to struggle.

Algiers, Havana, and the “revolutionary diaspora”

Though rooted in American ghettos, the Black Liberation Army never conceived its struggle as strictly local. Its militants saw themselves as the North American vanguard of a global war against imperialism. In the 1970s, two capitals became the nerve centers of this revolutionary diplomacy: Algiers and Havana.

In 1972, after the hijacking of Delta Flight 841, a group of BLA members forced the plane to land in Algiers. Boumediene’s Algeria was then a sanctuary for guerrillas and liberation movements: the victorious FLN hosted exiled Black Panthers, and Third World militants converged there. The airline ransoms became a contested treasure, but the essential lay elsewhere: the operation propelled the BLA into international revolutionary networks. In Algiers, militants found new legitimacy—that of a guerrilla inscribed in the vast theater of anti-imperialist struggles.

A few years later, Cuba became the true refuge. In 1984, Assata Shakur, exfiltrated after her spectacular escape, settled in Havana. Fidel Castro granted her political asylum, presenting her as a fighter persecuted by the American state. This choice went beyond a humanitarian gesture; it was a geopolitical act. By protecting Assata, Cuba positioned itself as protector of Black dissidents and symbolic counterweight to Washington.

Assata’s presence in Havana became a lasting point of contention between the two countries. At every diplomatic thaw, her name resurfaced as a stumbling block. For the United States, her protection was an insult, a permanent provocation. For Cuba, it was a demonstration of sovereignty and a reminder of its role as a beacon for the oppressed.

Within this revolutionary diaspora, Black American militants were no longer isolated fugitives: they became brothers-in-arms of Vietnamese guerrillas, Algerian fighters, South African militants. Through its international ties, the BLA sought to be part of a global front. And if its cells were crushed in the United States, its myth traveled.

1981–2000: endings and recompositions

The Brink’s robbery in Nyack in October 1981 marked the swan song of the Black Liberation Army. Three deaths—two police officers and a guard—mass arrests, and saturated media coverage sealed the image of the BLA as a criminal organization and justified, in the eyes of the state, the final crushing of the network. In the months that followed, remaining active members were arrested, sentenced to heavy terms, or died on the run. A decade of armed confrontation ended in blood and bars.

Yet while the BLA disappeared as an organization, its legacy endured in dispersed, often unexpected forms. A partial “anarchization” of the movement occurred: some militants, such as Ojore Lutalo, gravitated toward revolutionary anarchist circles and autonomous collectives, seeking to situate the Black struggle within a broader opposition to global capitalism. This ideological hybridization blurred boundaries and showed that the BLA, even defeated, continued to mutate.

During the 1980s and 1990s, solidarity networks took over. The Anarchist Black Cross, an organization supporting political prisoners, publicized the detention conditions of BLA militants, organized letter-writing campaigns, and raised funds for legal fees. In high-security prisons, BLA veterans became reference points, transmitting to a new generation of inmates a militant memory and a lexicon of resistance.

The 1990s also saw new judicial fronts open. Old cases were revisited, late legal disputes emerged, often linked to contested FBI methods and coerced confessions. Some militants obtained parole after decades of detention; others died behind bars, without official recognition of their status as political prisoners.

Thus, between 1981 and 2000, the BLA ceased to exist as an armed force but remained a spectral presence: dispersed in prisons, embedded in radical collectives, sustained by support networks. Its organic disappearance did not end its capacity to inspire. On the contrary, it prepared the ground for a subterranean memory that would resurface in twenty-first-century mobilizations.

Anatomy of a fertile defeat?

On a strictly military and organizational level, the Black Liberation Army failed. It never managed to build a durable mass front or rally the majority of Black communities to its project. Its clandestinity protected it from infiltration but isolated it from the people it claimed to liberate. Repression, relentless, did the rest: mass arrests, exemplary trials, life sentences, deaths on the run. The human cost was immense, and the BLA vanished in less than a decade, crushed by the American security machine.

And yet, to speak only of defeat would be incomplete. For the BLA bequeathed a symbolic capital whose effects endure. Its figures, from Mutulu Shakur to Assata Shakur, survived in militant memory. Its slogans were taken up, its texts republished, its words chanted in American streets long after its dissolution. The BLA lost the war, but it won a place in the Black political imagination: that of an organization that dared what others feared, that crossed the forbidden threshold of armed struggle.

This is where Assata Shakur’s death in 2025 takes on its full meaning. It does not close a story; it reopens it. It reminds us that the shadow of the BLA remains, and that it says something about contemporary America. For if this guerrilla emerged, it was first because the state refused to hear Black demands except through police and carceral violence. Today still, the police–prison–race triad lies at the heart of American debate. The BLA is gone, but the conditions that gave birth to it have not disappeared.

At bottom, its legacy is double. Practical defeat, yes—but rhetorical and memorial victory. The Black Liberation Army failed to liberate its people by arms; but it succeeded in imposing its existence as a brutal reminder that freedom, for some Americans, was never a gift but a struggle. In this sense, its memory is a scar—and like all scars, it speaks less of victory than of the persistence of the wound.

Notes and references

FBI Records – The Vault – Black Liberation Army, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Assata Shakur. Assata: An Autobiography. Lawrence Hill Books, 1987.

Williams, Evelyn. Inadmissible Evidence: The Story of the Battle to Free Assata Shakur. Lawrence Hill Books, 1993.

Austin, Curtis J. Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Alkebulan, Paul. Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party. University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Bloom, Joshua, and Waldo E. Martin Jr. Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press, 2013.

May 19th Communist Organization Papers, Tamiment Library, New York University.

The San Francisco 8 Case, National Lawyers Guild, 2008.

Fraternal Order of Police Reports (1970–1985).

Table of contents

Assata is dead, the BLA returns

Genealogy of a Black guerrilla

Identity card of the BLA

A red and black decade

Doctrine and internal debates

Police, FBI, and counterinsurgency

Dramatis personae

Algiers, Havana, and the “revolutionary diaspora”

1981–2000: endings and recompositions

Anatomy of a fertile defeat?

Notes and references