In this third part of our exploration of African survivals in Caribbean culture, we delve into the heart of the practices and customs that mark the great moments of life. Inspired by the essay “Survivances africaines” by Huguette Bellemare, published in Historial antillais. Tome I. Guadeloupe et Martinique. Des îles aux hommes (1981), this article examines how African heritage continues to color the rites associated with birth, first communion, and death in the Caribbean. Through this analysis, we discover how these traditions have adapted and endured in the Caribbean context, thus forming a unique culture deeply rooted in African history.

Numerous rites mark the great moments of life. Here again, the debate over their origins is extremely intense. However, in this field, the contributions of the two traditional peasant cultures—African and European—could only combine to form the traditional rural culture of the Caribbean. We will nevertheless attempt to show what we believe we owe more particularly to Africa in this domain—or, more simply, the “African coloring” of certain customs.

Birth

Certain beliefs and practices surrounding birth have their source in Africa. In particular, those related to trees: they are based on very clear analogical reasoning.

A pregnant woman can transmit her fertility to fruit trees by planting them or, if they are already planted, by “shoeing” them (driving a nail into them).

A pregnant or breastfeeding woman must not cut down a fruit tree.

The placenta and the navel of a newborn may be buried at the foot of a tree, which will transmit its vigor and longevity to the child.

But the major concern, in the Caribbean as in Africa, is the name.

In West Africa, it is customary to give children names linked to their date of birth (sometimes the name of the day of their birth), to the circumstances surrounding that birth, or to the child’s character or appearance.

In rural Martinique, this custom has persisted to the extent allowed by the control of the civil registry authorities.

Indeed, for a long time the first child was called Mon premier or Alfa, the last (or the one hoped to be the last) Ultima or Cétou; the particularly desired child Mongré or… Désiré(e), quite simply. A child born on the road is called Chimène. Children often bear the name of the saint of the day of their birth, hence the confusion that explains certain given names: Fêt-nat for a child born on July 14, or Circoncis for one born on January 1, Gloria for one born on the Saturday of Holy Week.

“(In Africa) the identification of a ‘real’ name with the personality of the one who bears it is considered so complete that this ‘real’ name, usually given at birth by a relative (but not by just any relative), must be kept secret for fear that it might become known to someone capable of using it in harmful magical practices directed against the bearer of the name.”

Melville Herskovits, L’héritage du Noir, Mythe et réalité, Présence Africaine, Paris, 1962.

In Martinique, one does not pronounce someone’s given name for fear that the forces of evil might seize it. Moreover, pronouncing someone’s name already means granting oneself a certain power over that person, as shown by this dialogue taken from a Caribbean novel:an antillais :

— “Emmanuel, Joseph, Maurice, you’re as sly as a rat… you’ll see what’s going to happen to you!”

— “By God’s thunder, was it you who carried me to baptism to keep repeating my given names every moment?”¹

This leads us to think that if there are so many nicknames in Martinique, it is in order to keep the real given name secret². We ourselves had a close relative of our generation whose given name was kept hidden until adolescence. It has also happened to us to ask a peasant woman the name of her baby and to hear the reply: “Ipas ni non,” which translates literally as “he has no name,” but in reality means that the child, not yet baptized, has his given name unspoken for fear that the Devil might seize it.

The belief that an individual’s name is part of his personality and power explains why children are sometimes given the names of prestigious figures whose power is admired. Thus, one can find in the Caribbean countryside (as in Africa) children named: De Gaulle, Stalin, or Napoleon.

Many customs concerning birth or early childhood are found both in the Caribbean and in Africa.

In Martinique, as in Africa, people walk around the house with the baby a few days after birth to present to it the places where it will live.

In Africa and among Black people in the United States, a frail child is “sold” in order to ward off bad luck and save it. In Martinique, in the same situation, the child is “consecrated” to the Virgin or to a saint whose color it will wear (to the exclusion of all others). Here, the African custom may have “poured itself into a Christian mold” in order to survive.

In Africa and in the United States, when a child is slow to walk, it is buried naked up to the waist; in Martinique, it is buried in sand if it has bowed legs.

First communion

This title may seem surprising in a study devoted to “African survivals” in Caribbean cultures. However, one can say of first communion what Bastide said of the great Catholic festivals: Black people accepted it as a “secret niche in which to celebrate their own festivals.”

Indeed, first communion in the Catholic Caribbean is an occasion for splendor and, more concretely, extraordinary expenses. The communicants—especially the young girls—vie with one another in elegance and beauty. This celebration is also the occasion for true feasts to which the most distant relatives, and even the simplest neighbors, are invited.

This profane aspect of the celebration developed to such an extent that religious authorities had to intervene, particularly to limit the sometimes ostentatious luxury of the outfits.

Why is such importance given to this sacrament?

It is because first communion “replaces the former puberty rites of slaves and savages” (E. Revert), which were forbidden by colonization and slavery—those rites that mark “access to the fullness of being, entry into society” (J. Corzani).

For young girls from disadvantaged backgrounds especially, who have very little chance of being married in church, the sacrament of first communion takes on particular importance as a rite of passage and initiation.

Mayotte Capécia illustrates this in her novel Je suis Martiniquaise:

“At last, my mother opened the door. I cried out in surprise. My room, which until then had been like a boy’s room, had become a young girl’s room. The bed had been covered with a beautiful fabric and, in one corner, I saw a shelf on which stood a statue of the Virgin with, before it, an oil lamp that I knew I would have to maintain so that it would remain lit night and day.

It was an altar like the one in my parents’ room, like those owned by all reasonable people.”

First communion thus allows the little girl to pass both into the world of adults and into that of women.

Another novel, Le Temps des Madras, confirms this interpretation in a comic mode:

“She hasn’t made her first communion and she’s singing a romance! It’s the end of the world!”

If slaves were able to assimilate initiation rites and first communion, it is because they presented remarkable similarities (age of the participants—between 9 and 12—retreat, fasting in both ceremonies). We thus see here one of the cases noted by Herskovits where similarities between two cultural elements reinforce one another.

Death

Beliefs and customs concerning death are extremely numerous in the Caribbean, and—once again—it is difficult to disentangle, within this abundance, the share attributable to each of the rural cultures that contributed to the formation of Caribbean culture (European culture, African culture, and—to a lesser extent—Amerindian culture).

As we did for birth, we will therefore attempt to identify the main ideas around which African and Caribbean death practices are organized: death is the most important moment of life, which is why it must be surrounded by splendor prepared long in advance. However, it is not irreversible, which explains a great familiarity with death, but also a danger: the dead may refuse to depart or seize any opportunity to return, and thus must be appeased through all kinds of attentions.

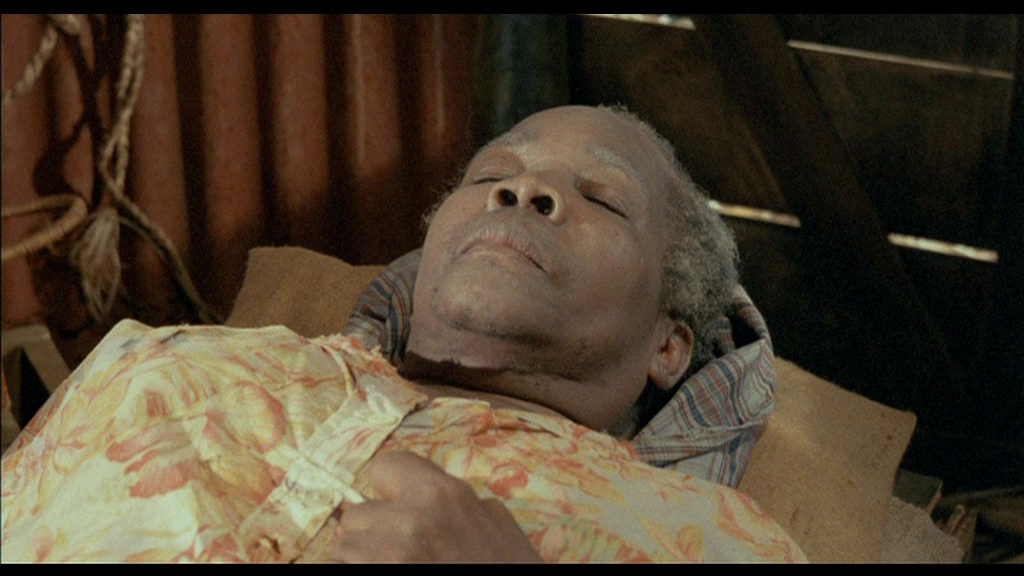

In all Black societies, funerals hold great importance. Consequently, the rites that follow death in the Caribbean are particularly numerous and meticulously observed. In Martinique, for example, after the washing of the body, the deceased is laid out in their finest clothes. Death is then announced to relatives and neighbors. In the past, in the absence of telephones, the announcement was made by ritually blowing “horn calls” into a conch shell.

After the wake, which lasts until dawn³, comes the burial, which gathers a crowd of relatives and friends who come even from very far away, abandoning all other business. At the cemetery, following a funeral oration that delivers a true dithyramb in praise of the deceased, the burial takes place. When the family can afford it, it owns a splendid vault, but even when it has only a modest grave, it will always be piously maintained.

The strict observance of all these rites is so important that everything is done, everything is planned, to ensure they are respected. Thus, the funeral oration may be composed in advance, as soon as the sick person is on their deathbed. Even more strikingly, in rural areas it is common for individuals to prepare their own funeral ceremony: they will have their coffin made in advance or, at the very least, purchase and store the planks from which it will be built; they will also buy a large demijohn of good rum and a packet of coffee beans for their wake. If the deceased is a woman, she will additionally have made the dress in which she wishes to be “displayed” and will buy the new sheet intended to serve as her shroud.

If death and the dead are so close, it is because death is not the end of life; it is only a passage. The deceased live another life and may, moreover, intervene—beneficially or malevolently⁴—in the lives of their descendants. That is why they must be given a proper burial and honored (hence the cult of the ancestors, which we will discuss later).

But this closeness of the dead, while beneficial to the community whose unity and stability it ensures, remains ambiguous. Indeed, if the deceased continue to live very close to us, they can return to the world of the living whenever they wish and may, first of all, refuse to leave it at the moment of death. Hence a whole series of practices intended, at the time of death, to make the spirit of the deceased depart and subsequently to allow it to return only on certain ritual occasions.

For example, new socks, still fastened together, are placed on the deceased, undoubtedly to bind their feet and keep them still.

An plate containing holy water and a tuft of goosegrass (a type of grass) uprooted with a large clod of earth is placed on the chest, with the stated aim of preventing the belly from swelling, but perhaps also to ensure immobility.

In the hills⁵, the body had to be carried on men’s backs, on a stretcher. The bearers leaped as they left the house of death, presumably to overcome the resistance of the deceased who refused to leave the place where they had lived.

Once the body had been taken away, all the water used for washing the body—kept until then beneath the bier—was thrown out in all directions.

The body was thus transported to the neighboring town. Just before entering the town, on the last bridge, an extraordinary ceremony took place: under the direction of the “body leader,” the bearers stopped, then took three steps forward and three steps backward, repeating this sequence three times before leaping once again over the body. This “dance of the body” certainly served to deceive the dead (to “lose” them) and to overcome their final resistance to departure.

Finally, once they arrived in town, the bearers placed the body on the resting platform and, standing facing it, each made the gesture of stretching and passed their hands over their entire body to throw back onto the deceased the fatigue and cramps contracted during the journey. In reality, this was most likely a rite of protection: the impurities associated with contact with the dead were returned to them.

Indeed—and this is yet another element of the ambiguous meaning of the care given to the dead—there is a common belief in “a kind of contagion of death” (Revert). Unable to remain among the living, the dead will attempt to take someone along with them. Contact with them is therefore dangerous, which explains the playful antics of the bearers, who try to strike one another with “blows of the body.” This is why a “body leader,” whip in hand, supervises them. Finally, at the cemetery, when burial takes place in a grave, each person must throw a clod of earth onto the coffin, undoubtedly with the same aim: to prevent the dead from coming to carry them off.

For eight days, prayers are said around the funeral bed, “on which a small oil lamp remains lit for eight days and eight nights” (Revert). On the ninth day, a ceremony similar to the wake is organized in the house of the deceased: the women, gathered around the funeral bed, pray and sing hymns; the men, outside or in the living room, drink. Then (at dawn?) the lamp is extinguished, the bed is dismantled, and a mass is said at which it is acknowledged that the deceased is present (the “departure mass”).

The spirit of the dead then departs definitively and will return only on very specific occasions. The descendants may therefore resume their daily lives with a peaceful mind—provided that all prescriptions have been correctly observed.

Indeed, it is generally believed that a deceased person dissatisfied with their heirs or with the circumstances of their death may return to seek revenge. Efforts are therefore made to fulfill the wishes expressed during their lifetime. Special masses are said to pacify the souls of those who died in atrocious circumstances—suicides, for example.

It is certainly this fear of the dead’s vengeance that explains the practice of charivari or chalbari. When a widower or widow remarries, the news is announced by the sound of a conch horn, and from the publication of the banns until the wedding day, every evening people from the neighborhood and surrounding areas gather around the house, creating mockery and a deafening din using pieces of cauldrons and metal. On the wedding day, this same orchestra accompanies the couple to the town hall, to the church, and then to their home.

“We have,” Revert tells us, “lost sight of the protective value that such manifestations originally held, seeing in them now only an occasion for mockery and amusement.”

Revert, Magie Antillaise, p. 35. For a description of this festival of the dead that is also a celebration of life, see Diab’la by Zobel, pp. 140–150.

In the Caribbean, All Saints’ Day is an important moment in the cult rendered to the dead. It is prepared long in advance: people go to the cemetery to clean and repaint the tombs, weed the graves, ask children (for payment) to fetch fine sand to spread over the graves, and to redo inscriptions erased since the previous year. Then, on the evenings of November 1 and 2, comes the illumination: thousands upon thousands of candles are lit on the tombs.

“Families are there, close to their departed. People come to shake their hands and talk with them a little. It is an uninterrupted procession, while outside unfolds—though greatly amplified—the same noisy celebration as at the wakes.”

Revert, Magie Antillaise, p. 31.

Revert gives us the meaning of these celebrations:

“It is explicitly acknowledged that the souls of the departed then receive permission to return to see the earthly scene and to spend a few hours, from midnight to midnight, in the intimacy of their loved ones.”

Some people also light candles around their homes to allow “their” dead to find their way back to the places where they once lived. It is so widely accepted that the dead live on that night and see and appreciate what has been done for them that real battles sometimes break out around certain graves to “appropriate” the spirit of the deceased. For a description of one of these disputes, see the already cited passage from Diab’la.

Another popular belief holds that the nocturnal birds flying over the cemetery at that time are the souls of the dead who, thanks to the care of the living (prayers, illumination), leave purgatory and return to paradise.

Contents

Birth

First Communion

Death

Notes and References

Fr. Ega, Le Temps des Madras. During a public meeting, an honest man protested indignantly: “I titroyé moin.” “He called out my title, that is to say my (family) name!”

In Martinique, a nickname is the nom vante (from the French vent, wind), meaning, most likely, the name that can withstand public exposure without harm to the person concerned (unlike the baptismal name).

See Ina Césaire’s contribution in this volume.

Or mischievously: if you do not take care of one of your dead, they may come and pull your feet or touch you, leaving a “bruise” at the point of contact.

All the information concerning funeral ceremonies in the mornes was given to me by my father, who spent his youth in one of these mornes, Rivière-Salée, where he himself witnessed these practices and even took part in them.