In 1971, at the age of 19, he became the youngest head of state in the world. Son of “Papa Doc,” Jean-Claude Duvalier inherited a throne built on fear. Fifteen years later, on February 7, 1986, “Baby Doc” fled Haiti, driven out by the anger of a people he had lulled with luxury, corruption, and terror. From glory to exile, this is the story of a fallen tropical king and of a country taken hostage by its own memory.

The gilded fall of the last black king of the caribbean

Port-au-Prince, February 7, 1986. Sirens wail, crowds flood the streets, statues of the “Doctor” are toppled. Inside the National Palace, a young man with a soft voice, smooth face, and vacant gaze prepares to flee. At 34, Jean-Claude Duvalier, president for life of Haiti for fifteen years, leaves his country to the cries of “Down with Duvalier!”

An American plane awaits him on the tarmac. In his luggage: millions of dollars in cash, jewelry, and the remnants of a power inherited more than conquered. That day, one of the last vestiges of tropical dictatorships collapses. But behind the flight of “Baby Doc” lies the deeper story of a broken country, of a family power elevated to divinity, and of a people who never ceased to seek freedom.

To understand Jean-Claude Duvalier, one must first understand his father, François “Papa Doc.” A physician, noirist intellectual, and populist, he came to power in 1957 promising to return Haiti to the Black masses after decades of mulatto domination. His rhetoric inflamed racial pride; his authority was imposed through fear. Papa Doc built a personal regime based on the cult of the leader, the terror of the Tontons Macoutes, and the manipulation of Vodou as a political weapon.

He proclaimed himself president for life, modeled his image on spirits from the Vodou pantheon, and styled himself “Baron Samedi in the flesh.” Haiti became a kingdom without a crown, a tropical theocracy where death guarded power.

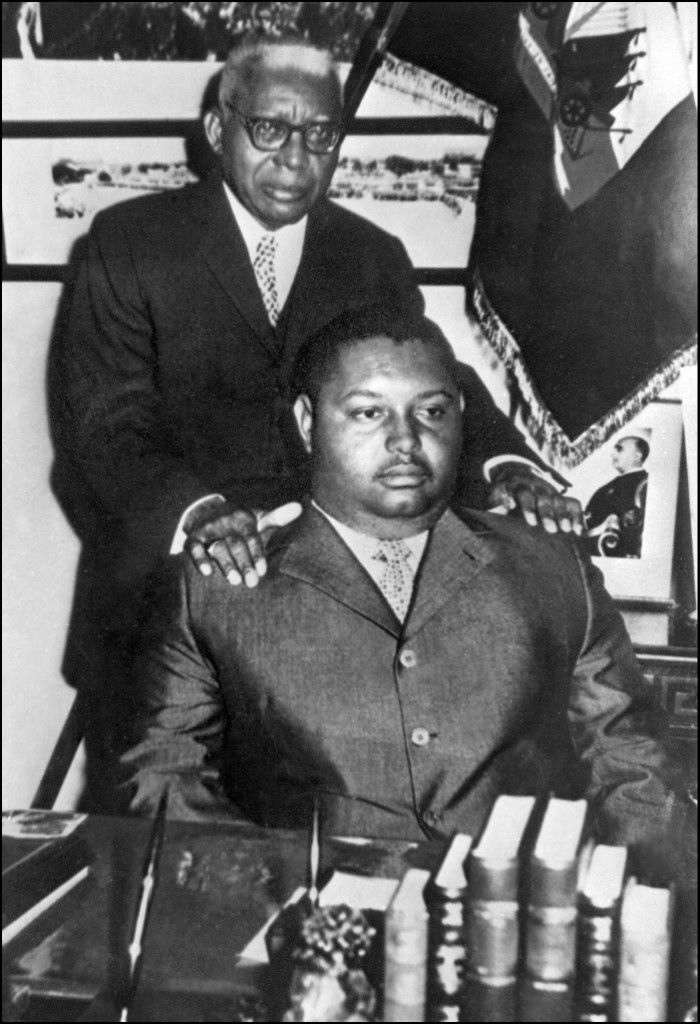

When Papa Doc died in April 1971, his nineteen-year-old son inherited the throne. Jean-Claude became the youngest head of state in the world. A rigged referendum ratified the succession: over 2.3 million votes in favor, fewer than three hundred against. Behind the scenes, real power lay with his mother, Simone Ovide Duvalier. Though the regime claimed dynastic continuity, the young president lacked both his father’s cruelty and his mystical fervor.

Jean-Claude Duvalier loved sports cars, Swiss watches, parties, and trips to Paris. Around him, a court of eager advisers turned the state into a machine for generating foreign currency. The successor to the dictator was not a bloodthirsty tyrant but a prince of carelessness.

Appearances, however, were misleading. Under Baby Doc, Duvalierism modernized. The regime’s relative opening appealed to Washington during the Cold War. By releasing a few political prisoners and reopening the economy to foreign investors, Duvalier Jr. created an illusion of reform. The United States resumed its aid; Europe cautiously returned. Commentators spoke of a “new beginning” for Haiti.

The façade soon cracked. Behind the young president’s smile, the structure of power remained unchanged: mass surveillance, torture, censorship, omnipresent militias. The Macoutes continued to terrorize the population. The state remained a gateway for personal enrichment.

The economy relied on international rents, smuggling, and foreign aid. The Tobacco and Matches Monopoly, created under Papa Doc, functioned as a secret treasury. Millions in U.S. aid were diverted to sustain the clan, buy loyalties, and finance extravagance. Literacy campaigns were cosmetic; hospitals decayed; peasants sank deeper into poverty. Rural exodus accelerated. In Port-au-Prince, slums expanded, and a generation of unemployed youth simmered with contained anger.

In 1980, Jean-Claude Duvalier married Michèle Bennett, an elegant young woman from the high mulatto bourgeoisie. Her wedding dress reportedly cost $70,000. The ceremony, staged like a fairy tale, cost the Haitian state more than two million dollars. The contrast was striking: the “son of the Black people” married an heiress of the white elite. Papa Doc’s former noirist allies cried betrayal. This marriage shattered the racial balance underpinning the dictatorship. By aligning with the Bennett family, Duvalier Jr. broke with his father’s noirist myth.

Luxury became obscene. The Duvaliers flaunted wealth in an impoverished country. Scandals multiplied: a personal fortune estimated at $900 million, diversion of humanitarian aid, suspicions of drug trafficking and money laundering. State coffers emptied as corruption spread. Michèle Bennett ruled as first lady, distributing privileges and contracts to her circle. The clan enriched itself while the country collapsed.

In the early 1980s, Haiti entered a triple crisis. First, a rural catastrophe: in 1982, swine fever devastated livestock. Under U.S. pressure, the government ordered the mass slaughter of Haitian pigs—the peasants’ main savings. Thousands of families were ruined. Second, an economic crisis: tourism collapsed, exacerbated by Haiti’s association with the AIDS epidemic. Third, a moral crisis: the Catholic Church, once cautious, openly opposed the regime.

In March 1983, during his historic visit to Port-au-Prince, Pope John Paul II uttered a sentence that shook the palace:

“Something must change here.”

The words became the rallying cry of an entire nation.

Youth, priests, and teachers mobilized. In 1985, protests erupted in Gonaïves, Cap-Haïtien, and Les Cayes. Repression left dozens dead. Images circulated clandestinely. The United States, under Ronald Reagan, withdrew its support: the dictator was no longer useful. In January 1986, the situation became untenable. On February 6, Washington demanded Duvalier’s immediate departure. The next day, he boarded a U.S. Air Force C-141 bound for France.ain, il monte dans un avion C-141 de l’armée américaine. Direction : la France.

Jean-Claude Duvalier settled first in Grasse, then in Théméricourt, in Val-d’Oise. France officially denied him political asylum but tolerated his presence. He lived comfortably, surrounded by family and loyalists. Meanwhile, Haiti struggled to heal: massacres, reprisals, aborted truth commissions. Investigations into the Duvaliers’ stolen assets dragged on. In 1988, Jean-Claude and Michèle divorced. The Bennetts withdrew; the millions vanished; the palaces emptied. The former president for life lived modestly, nostalgic for his tropical throne.

In 2011, to widespread astonishment, Jean-Claude Duvalier returned to Haiti, still traumatized by the 2010 earthquake. He claimed he wished to help rebuild the nation. In reality, his goal was more pragmatic: to recover funds frozen in Switzerland under the “Lex Duvalier,” which mandated their return to the Haitian state. He hoped to recast himself as a patriot to negotiate his fortune.

The plan failed. His return triggered surreal scenes: some hailed him as a savior, others demanded his immediate arrest. He was indicted for crimes against humanity and corruption, but the trial never took place. Judicial delays, political pressure, and state weakness buried the case.

Jean-Claude Duvalier died on October 4, 2014, in Pétion-Ville, of cardiac arrest. No national mourning was declared. Authorities issued a neutral statement:

“Haiti has lost a former head of state.”

Public reactions were divided. Some prayed for the “president of order”; others celebrated the end of impunity. The ghost of Duvalierism, however, continued to haunt the country.

His legacy remains ambiguous. Duvalierism left a deep political and psychological imprint: a cult of leadership, social fragmentation, fear of the state, institutional violence. Papa Doc had forged an ideological dictatorship rooted in fear and Black mysticism; Baby Doc turned it into a hollow luxury monarchy, emptied of ideology but rich in foreign currency. The regime’s fall freed speech but not the system.

Some contemporary political figures still invoke the “Duvalier era,” praising its discipline and supposed stability. In a fractured country, authoritarian nostalgia is never far away.

Jean-Claude Duvalier ruled for fifteen years without ideology, governed without charisma, and fled without glory. Neither a terror like his father nor a reformer, he was merely the heir to a bloody throne, which he squandered like a misunderstood family inheritance. His death without judgment closed a chapter without resolving the story.

Duvalierism did not disappear; it mutated. It survives in distrust of institutions, in the latent violence of Haitian politics, and in a collective memory torn between fear and regret. The weakened Haitian state still bears the scars of the dynasty. Haiti continues to oscillate between memories of order and awareness of the human cost it exacted.

Jean-Claude Duvalier died as he lived: surrounded by privileges, but cut off from the people. His story is that of a dynasty that transformed Haiti’s Black revolution (the first free Black republic in the world) into a monarchical caricature. By claiming to embody Haitian pride, the Duvaliers emptied the country of its substance, diverting the dream of independence into an authoritarian nightmare.

In 1986, the crowd chanting “Down with Duvalier” believed it was ending fear. But in Haiti’s memory, dictatorship never fully dies. It changes faces, reinvents itself, and waits for the next crisis to return. The Duvalier dynasty has vanished, but its shadow continues to float over the National Palace like a warning: Haiti’s history is that of a people who have never stopped surviving their kings.

Notes and references

Abbott, Elizabeth. Haiti: The Duvaliers and Their Legacy. McGraw-Hill, 1988.

Diederich, Bernard & Burt, Al Burt. Papa Doc and the Tontons Macoutes. Penguin Books, 1970.

Diederich, Bernard. The Price of Blood: Haiti Under the Duvaliers. Spartan Press, 1991.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Haiti: State Against Nation. Monthly Review Press, 1990.

Wilentz, Amy. The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier. Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Fatton, Robert Jr. Haiti’s Predatory Republic: The Unending Transition to Democracy. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002.

Rotberg, Robert I. Haiti: The Politics of Squalor. Houghton Mifflin, 1971.

Farmer, Paul. The Uses of Haiti. Common Courage Press, 1994.

Schmidt, Hans. The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press, 1995.

Dupuy, Alex. Haiti in the World Economy: Class, Race, and Underdevelopment Since 1700. Westview Press, 1989.

Hallward, Peter. Damming the Flood: Haiti and the Politics of Containment. Verso, 2007.

Human Rights Watch. Haiti – Duvalier Case: Victims Demand Justice. HRW Report, 2011.

Le Monde. “Haïti: la mort de Jean-Claude Duvalier, l’ancien dictateur surnommé Baby Doc.” October 4, 2014.

The New York Times. “Haitians Celebrate as Duvalier Flees into Exile.” February 8, 1986.

Agence France-Presse (AFP). “Baby Doc’s Return Reopens Haiti’s Old Wounds.” January 18, 2011.

CIA Declassified Reports. “Haiti: Prospects for Political Change, 1985–1986.” National Security Archive, 1986.

Amnesty International. Haiti: Human Rights Violations Under the Duvalier Regime. Report, 1983.

Summary

The Gilded Fall of the Last Black King of the Caribbean

Notes and references