Blind, enslaved, a piano prodigy, Blind Tom Wiggins fascinated America while remaining a prisoner of his chains. This portrait explores the confiscated virtuosity of a Black genius, captive to the white gaze, and questions a memory still on trial.

Music stronger than chains

He played as one breathes, without apparent effort, yet with an intensity that stirred crowds. Blind Tom Wiggins, born blind, Black, and enslaved in 1849, became one of the most acclaimed (and highest-paid) pianists of his century. He was led from stage to stage like a sonic trophy, a glorified anomaly. He performed concertos, mimicked politicians’ speeches, played three pieces at once… But he never played for himself. The keyboard, immense, welcomed him; the world, meanwhile, kept him caged.

For there is in the story of Blind Tom a brutal irony, almost indecent: the man who offered the beauty of harmony to an America at war with itself had no right to sign his own compositions. While his talent dazzled audiences, his body remained the property of white men—first enslavers, then legal guardians. America lent him applause, never freedom.

In this paradox lies the full symbolic weight of Tom Wiggins. In him are condensed the tensions of a country that celebrates Black exception while fearing Black recognition. A country capable of making a former slave a star while refusing him a name, a bank account, a will.

How does the destiny of Blind Tom Wiggins—enslaved child, musical genius, entertainment tool—reveal the fundamental contradictions of American society, torn between fascination with Black talent and refusal of Black humanity?

This text proposes a journey in three movements: first, the childhood of a prodigy shaped within the violence of the slave institution; then, the career of an artist reduced to a spectacular object; finally, the unstable, contested, and reclaimed memory of a man whose notes continue to haunt history.

The birth of a musician under constraint

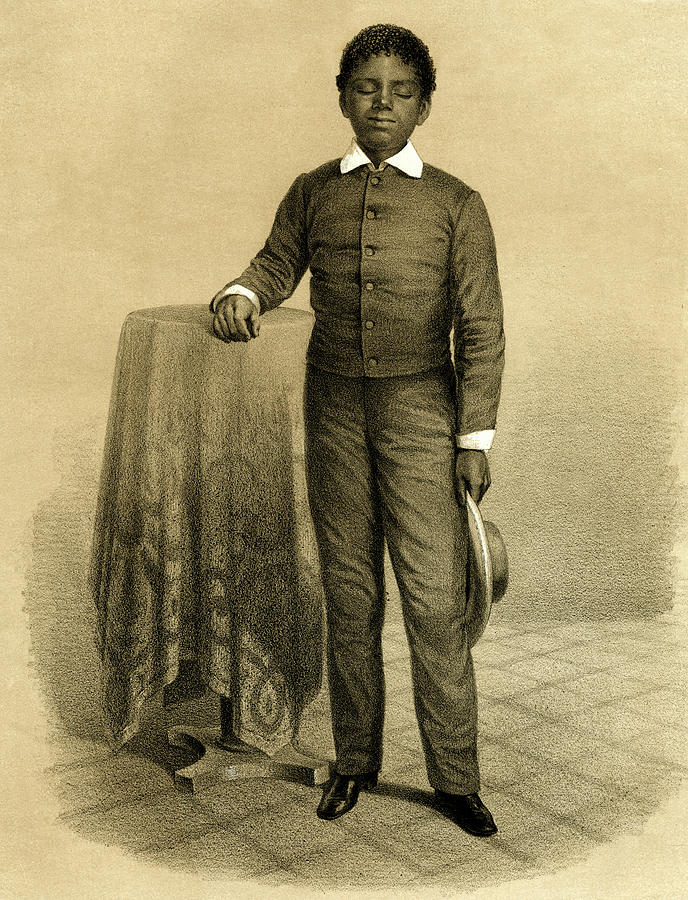

He was born without sight, in a world obsessed with controlling what it sees—and what it owns. In May 1849, on a plantation in Georgia, Thomas Greene Wiggins came into the world in the darkness of blindness, and in the denser darkness of slavery. At one year old, he was sold with his parents to a certain James Bethune, a lawyer, man of letters, and fervent defender of secession. In this transaction, he was not a child, not even a body: he was property, a line in an inventory.

Blind—therefore useless by the standards of the slave economy. He could not harvest, patrol, or labor in the fields. And it is precisely this “uselessness” that placed him at the margins; in a blind spot of the system, far from the whip but not free for all that. There, in the neglected space of shadow, he began to listen. Intensely. He listened to the sounds of the farm, the voices of whites, birdsong, the pulse of wind against the walls. He reproduced. He mimicked. He transformed. His blindness, seen as a curse, became for him a borderless territory, a sensory workshop. Where the slave order saw a burden, a miracle was preparing.

But this miracle would never belong to him. The gaze cast upon him would always be tainted—by astonishment, contempt, exploitation. The child was not a subject of care; he was an investment. A phenomenon. The piano became his extension, his way of inhabiting a world that recognized neither his voice nor his will.

With Blind Tom, the world was not seen; it was translated into vibrations. Before words even took shape in his mouth, he spoke in echoes. The song of a thrush, the drip of a drop onto a metal basin, the rumble of a carriage on packed earth—all became scores to be replayed. His acoustic memory was an endless labyrinth: at four, he repeated entire conversations, captured intonations, reproduced political speeches like a possessed oracle.

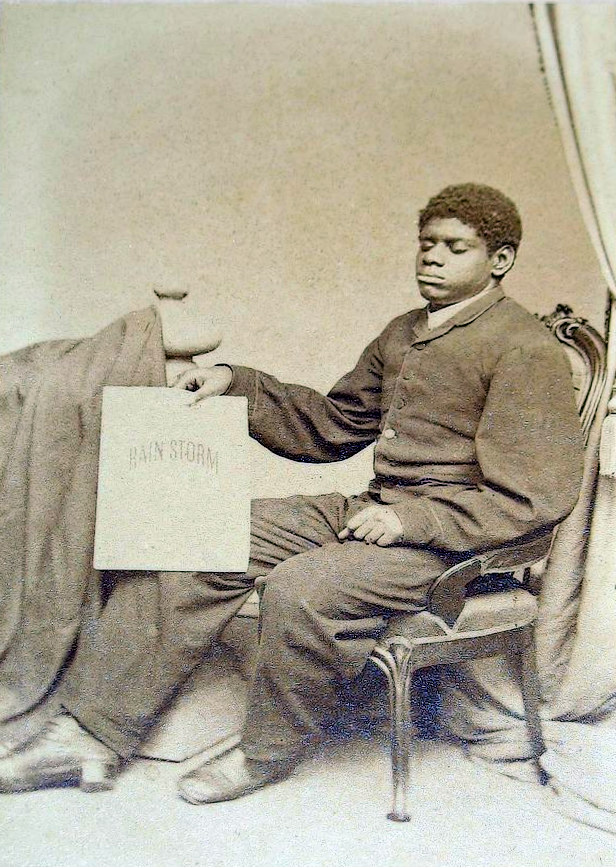

At five, he composed. A torrential rain beat down on the roof of the Bethune house, and Tom, fingers guided by the storm, invented The Rain Storm. More than a piece, it was a declaration of existence. Where other children draw, stutter, or cry, he improvises. For Tom, music was not an aptitude; it was his first language, his voice of survival.

This precocity astonished the whites who observed him. But it did not emancipate him. It made him spectacular. His difference, rather than earning protection, became a sales argument. They listened to him play, made him replay, but no one heard him. His silence about himself was compensated by the precision with which he resurrected everything he had heard. Performance became prison.

And yet, behind the talent lies a poignant truth: Tom did not play to shine, nor even to please. He played because it was the only way he had to say he was alive in a world that never addressed him. In the notes he lined up like words, an entire soul searched for its syntax.

He could have been a composer in his own right, a teacher, a full citizen. But America was not ready for that. Blind Tom entered history not as a musician but as a freak phenomenon; a Black miracle packaged in the codes of white entertainment.

From the age of eight, Tom was “rented out” by his master Bethune to a promoter, Perry Oliver. He was made to play everywhere—up to four times a day—before stunned white crowds, fascinated not by his music but by what he represented: the living contradiction. Black, enslaved, disabled; yet more virtuosic than any white child they had seen. That was the attraction. And that was also the trap.

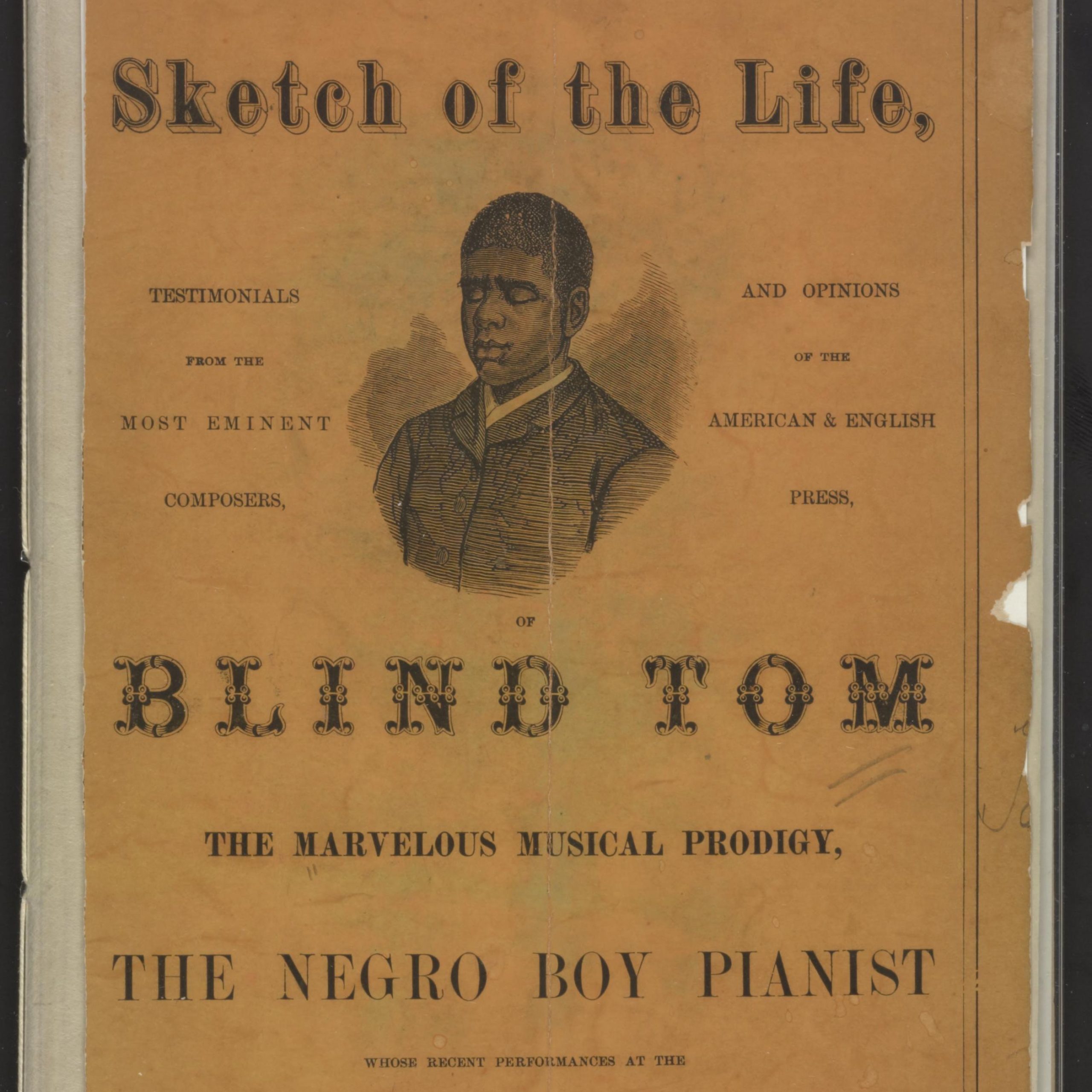

Posters compared him to a trained monkey, a trained bear, a “divine idiot.” He was not an artist; he was an “exceptional product.” His ability to reproduce a concerto after a single hearing was praised as a circus praises its acrobats. Tom’s genius became a “counter-nature,” a biological argument disguised as spectacle: see how even a Black person can be a genius… provided he remains docile.

In 1860, he played at the White House before President James Buchanan—the first African American invited there as an artist. The first, yet still without a name, without a contract, without nationality. The country could applaud him without granting the essential: belonging. He was not there as a citizen; he was there as a useful myth, as perverse proof that America could “recognize” Black talent while refusing the Black person.

The paradox of Blind Tom thus became that of an entire nation: able to listen without hearing, to admire without recognizing, to applaud while dispossessing.

A Black body in the service of white spectacle

It is said he was one of the highest-paid pianists of his time. This is true. Blind Tom generated up to $100,000 a year—the equivalent of several million today. Sold-out halls, tours across the United States and Europe, tickets sold at exorbitant prices. And yet he died without a bank account, without property, without a will. He owned nothing. Not even his name.

The money passed through his fingers like the keys of the keyboard. It went to his exploiters: first the Bethune family, then successive managers who fought over his guardianship through lawsuits. Tom was not a beneficiary; he was a deposit. His genius was extracted like oil from a well. He played; they collected. He fascinated; they capitalized. No one asked his opinion, offered a contract, or envisioned a future—only that he remain silent and replay what was expected of him.

And the cruelest part was not only financial extortion. It was the simulacrum of freedom. In the public eye, Tom was a famous artist, a revered prodigy, a “free” man after the end of slavery. But his daily life remained that of a hostage child—an infantilized adult, manipulated, maintained in total psychological dependence. His tours were not the fruit of choice. They were the cogs of a system.

This imposture—being celebrated while captive—is the beating heart of his tragedy. For in post-slavery America, Black genius was tolerated only if it remained under control. What Tom embodies is this permanent tension between admiration and negation, between public applause and intimate erasure. He became famous without ever becoming free.

He spoke of himself in the third person: “Tom is happy today.” “Tom wants to play.” This was not affectation. It was a fracture. Blind Tom, on stage and in life, seemed cut off from himself; spectator of his own body, messenger of a mind he was denied. Diagnosed as an “idiot savant,” he was reduced to a set of symptoms. His genius was not a gift but a pathology—an exception medicalized rather than an artistic singularity.

Tom reproduced everything—political speeches, birdsong, train noises. But he did not speak. Or rather, he did not speak for himself. He answered with echoes, quotations, learned gestures. His identity dissolved into the expectations of those who managed him—managers, promoters, spectators. What was called talent was less expression than repetition. And in that repetition lay dispossession.

Music posed a cruel dilemma: was he a creator or a mirror? Did he compose The Rain Storm, Battle of Manassas, Water in the Moonlight by his own will, or through unconscious mimicry? Critics still argue. For some, he was only a “human phonograph,” a memory machine. For others, he was a visionary composer shackled by an environment that refused him speech. One saw a genius; the other, a puppet.

Behind this controversy, one truth remains: his art was filtered, channeled, emptied of political dimension. Tom was not allowed to choose his pieces, his words, his silences. His strangeness fascinated only so long as it remained legible to the white gaze, so long as it did not challenge the order of things. And this very neutralization—the stripping away of meaning—may be the greatest violence inflicted upon him.

He could have been a symbol of resilience, a cry of freedom disguised as harmony. But Blind Tom Wiggins’s work was caught in a narrative trap: too Black to be celebrated in classical circles, too “collaborationist” to be honored in African American memory.

The case of The Battle of Manassas is the most emblematic. Composed to glorify a Confederate victory at Bull Run, the piece reenacts Southern cavalry, cannons, clamor. It fascinates through complexity—battle sound effects, shifting registers, rhythmic virtuosity. But the symbol disturbs. How could a former slave have put his art in the service of those who would have preferred him in chains?

The question is brutal, and history offers no easy answer. Tom had no power to impose his intention. This piece, like many others, was likely inspired, suggested, dictated. He did not play it to glorify, but because he was persuaded to, because it was the price of remaining visible. Yet this ambiguity was enough to distance Black intellectuals of the time. African American newspapers refused to claim him. He was banished from the pantheon—a genius, yes, but a suspect one.

Thus Blind Tom remained trapped in tension: between feat and shame, virtuosity and presumed submission. For white audiences, he became a docile mascot, living proof that the racial order could tolerate an exception—provided it did not speak, write, or choose, and played endlessly the music of the defeated South. For his own people, he was a lost brother, too praised by the oppressor to be embraced without discomfort.

His work, in many ways, occupied a gray zone—neither fully submissive nor entirely free. It reminds us that even the greatest talents can be instrumentalized, that the piano too can become a cage: gilded, publicized, yet locked.

Blurred legacy, recomposed memory

As America entered the twentieth century, Blind Tom exited it—not physically (he was still alive) but symbolically, socially, culturally. His music fell silent, his name faded, his body became a legal stake. It was not old age that removed him from the stage; it was the exhaustion of a system that had used him to the bone.

After John Bethune’s death in 1884, a war of possession erupted around Tom. The widow, Eliza Stutzbach, claimed custody, supported by lawyers as interested as they were protective. Tom’s mother, Charity, tried to intervene to obtain income from her son. In vain. The courts ruled in Eliza’s favor—not in the name of Tom’s autonomy (which he never had) but as one would decide the custody of a living inheritance, a declining asset.

From the 1890s on, Tom gradually disappeared from public life. He stopped touring, confined to a house in Hoboken where, it is said, he played late into the night—alone, without audience, without program. He continued to play, but no longer performed. The artist had become a ghost.

In 1908, he died in anonymity, victim of a stroke. He left no will. No fortune. And above all, no recording—no cylinder, no disc, no tape. He was one of the most heard musicians of his time; yet his musical voice did not cross the century.

This posthumous silence, heavy and unjust, may be the greatest violence of all. Tom Wiggins lived without freedom, died without heirs, and was buried without traces. He was a sonic monument—turned by history into a parenthesis.

For decades, his name lingered in a strange obscurity: too famous to be forgotten, too embarrassing to be celebrated. Only at the end of the twentieth century did the memory of Blind Tom Wiggins begin to reemerge, slowly, like a ghost refusing to dissolve.

African American artists, scholars, and writers were the first to retrace his steps. Contemporary composers replayed his pieces, thought lost, from rediscovered scores. In 1999, pianist John Davis recorded John Davis Plays Blind Tom, offering the first modern listening of music that had survived only as echoes. Essays by figures such as Amiri Baraka and Oliver Sacks accompanied this resurrection, blending science, culture, and symbolic repair.

The theater took it up as well: HUSH: Composing Blind Tom Wiggins illuminated the man behind the myth, exploring the gulf between performance and person. Documentaries, exhibitions, and an award-winning novel (The Song of the Shank by Jeffrey Renard Allen) nourished this critical rereading. No longer the “mad savant” or the “curious genius,” what fascinated was the stolen man, the erased history.

But the title that strikes, that sums everything up without resolving it, is often repeated: “the last legal slave in America.” This is not a metaphor. Until his death, Tom Wiggins was under guardianship, without financial autonomy or legal recognition of his identity. This title, both tragic and accusatory, turns his biography into an indictment—not against him, but against a country that could applaud a Black child on stage while keeping him captive backstage.

Can one honor a life without acknowledging its confinement? Can one celebrate a musical genius whose every note was extracted under contract, played in halls where he had no right to sit anywhere but at the piano? Blind Tom Wiggins’s question is not only about art. It is about the right to history, the right to truth, the right to a whole memory.

Tom was never free—not in his body, not in his mind, not in his trajectory. What America celebrated in him was not the beauty of his compositions; it was the Black exception—useful because inoffensive, spectacular because isolated. He was the ideal artist of a nation that admired Black talent provided it could exploit it without disturbance. That is what makes him so elusive in collective memory: at once prodigy and prisoner, virtuoso and victim.

Even today, his memory staggers between two narratives: one invoking him as a pioneer of African American music, the other hesitating to place him in a pantheon of resistance. For his life was not that of a militant, a writer, or one emancipated by speech. It was that of an instrument—magnificent, moving, but manipulated.

The memory of Blind Tom remains on trial. It is not his virtuosity that is questioned—it is unquestionable. It is what it reveals, what it forces us to face: a country capable of producing beauty while maintaining barbarism. A country where the piano could be a trap, and applause a disguise.

The piano does not lie

Blind Tom played everything—war, rain, hymns, cries. He played storms and speeches, birds and battles. He replayed the world without commenting on it, because he was never invited to speak it. And perhaps that is the tragedy: this voiceless virtuosity, this splendid music bearing the imprint of an imposed silence.

For Tom never played his own voice. He had neither the space nor the right. What was called “prodigy” may have been a masked cry, a lament coded into arpeggios, a revolt murmured between scales. Every key he struck, every chord he made vibrate, was an act of presence in a world that had reduced him to an anomaly.

His story does not merely ask to be told. It demands repair—not economic repair (it is too late for that) but memorial, ethical, political repair. It forces us to confront what America has done to its Black artists, its brilliant children, its marginalized voices. It forces us to hear, beyond talent, the price of invisibility.

The piano does not lie. It still resonates. And in its vibrations lies a truth we can no longer ignore.

Sources

O’Connell, Deirdre. The Ballad of Blind Tom: America’s Lost Musical Genius. Overlook Press, 2009.

Southall, Geneva Handy. Blind Tom: The Black Pianist-Composer: Continually Enslaved. Scarecrow Press, 2002.

Davis, John. John Davis Plays Blind Tom. CD & booklet, 1999.

Table of contents

Music stronger than chains

The birth of a musician under constraint

A Black body in the service of white spectacle

Blurred legacy, recomposed memory

The piano does not lie

Sources