She was a horsewoman, a warrior, and the mother of an empire. But who was Yennenga, really? Straddling the line between founding myth and feminist emancipation tale, she stands as a central figure in the Mossi identity and the history of Burkina Faso.

The epic of a horsewoman

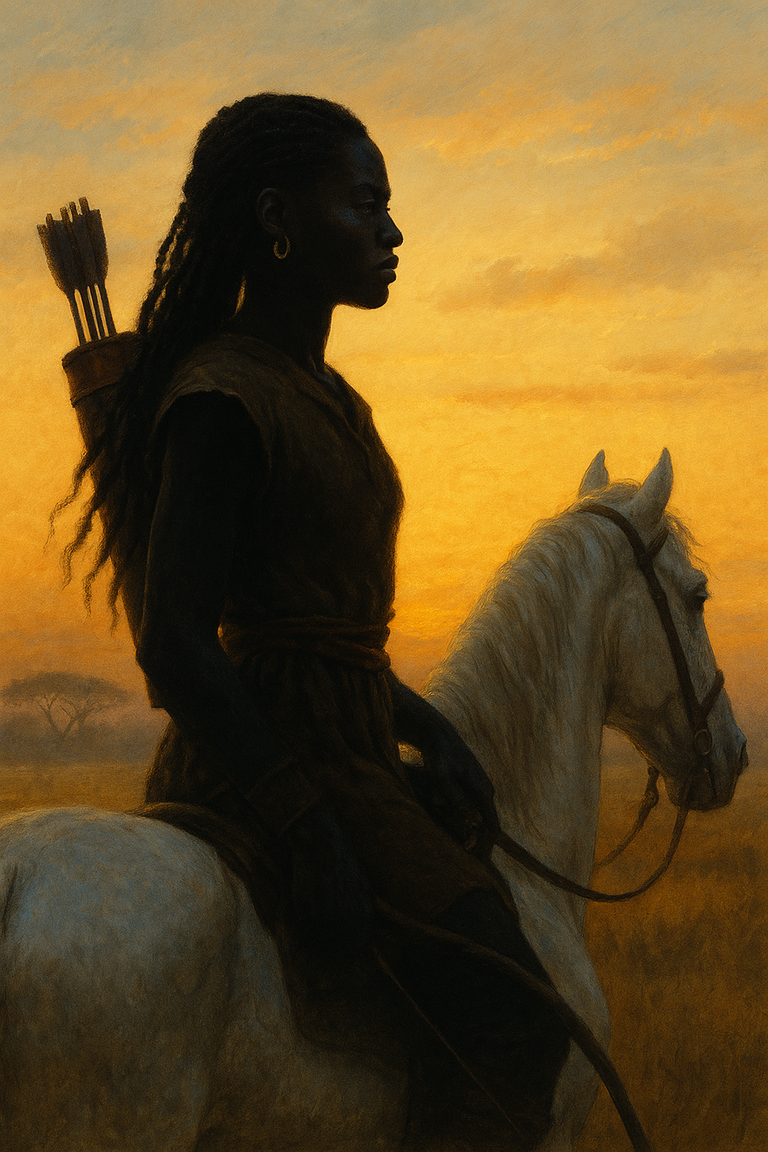

At daybreak, the Yatenga plains stretch out, still moist from the night. An ochre mist dances over the tall grass, and the warm wind, heavy with red dust, whispers through the drums of silence. Nothing can be heard but the breath of dawn… and of a horse.

She appears like a mirage. Astride a pale-coated stallion, a young woman cuts through the haze, upright, proud, determined. A bow slung over her shoulder, her braids neatly tied, she wears a tunic that moves with her like cotton armor laced with grace. She does not have the age of queens, but she already bears the gaze of someone who knows she will not be forgotten.

Before the state, before written history, before books and official genealogies, there was a woman on horseback. A rider. A king’s daughter. A warrior breaking away.

Her name was Yennenga.

This is not merely the story of a rebellious princess. It is the tale of a people born from refusal, from escape, from free love. A nation founded not by conquest, but by a woman who chose to chart her own course in a world of kings and men.

And if Yennenga is now cast in bronze in public squares, sung about in tales, and used as a national emblem, we must ask what this story tells us—about ourselves, about Africa, about our forgotten heroines and the making of myths.

This is no fixed chronicle. It is a living memory, weaving oral tradition and political reinterpretation. And behind the glow of legend, perhaps lies another truth: the story of a woman not recorded on parchment, but still galloping through the veins of a continent.

Dagomba, the kingdom before borders

Long before borders were named, and long before “Upper Volta” was stamped on official papers, what is now northern Ghana was a crossroads. A woven place, shaped by hooves, swords, and palaver. It was called the Kingdom of Dagomba—land of horsemen, merchants, blacksmiths, and griots.

It was here that Yennenga was born—not into a void, but into a world already dense, structured, and in motion.

In the 11th century, the Sahelian kingdoms formed a vibrant necklace: Ghana, Gao, Kanem, Djenné, Dagomba… all immersed in a current of exchange—gold, salt, cotton, but also knowledge and legends. Armies moved fast, on horseback or camelback, carrying languages, hairstyles, gods, and princesses.

At the time of Yennenga, Dagomba was not a peripheral kingdom. It was a strategic hub between the Hausa states to the east, the Mandingue communities to the northwest, and the Akan peoples to the south. It had royal codes, initiation systems, formidable chieftaincies, and women—yes, women in power. Not decorative. Decisive.

Yennenga’s father, King Nedega, ruled his kingdom with rigor. He trained her from childhood in martial arts, horsemanship, and military strategy. She was not an anomaly, but the heir to a lineage of female leadership often erased in colonial accounts. Because History—as it has been taught—has often stripped Africa of its horsewomen.

And yet, they were there. Fulani queens, Soninke warriors, Dogon matriarchs…

The Sahel at the time was no barren monolith of patriarchy. It was more complex, nuanced, and contradictory. Like Yennenga.

The legend of Yennenga

The elders say she wielded her bow like an extension of her will. At fourteen, Yennenga already fought alongside her father’s warriors. She rode in the front lines, hunted down raiders, and defended the borders. She was more than a king’s daughter—she was his right hand.

But the same father who praised her on the battlefield refused her a husband. Nedega would not give her away—neither to a man nor to another kingdom. So he confined her to the role of warrior, while denying her that of a free woman.

This is where the fracture begins.

Yennenga, the formidable and loyal, felt the injustice. She asked to wed. Her father refused. She insisted. He shut the gates. So she fled. Disguised as a man, on horseback, she crossed savannas and forests, defying the invisible borders of the time.

What followed is blurry—as all myths are. There’s talk of an injured horse, an old hunter, a forest hideaway. There, Yennenga is said to have met a young man, Rialé—a solitary farmer or forgotten prince, depending on the version.

They fell in love, far from the turmoil. From their union came a son: Ouedraogo, “the stallion boy,” named in honor of the white horse that carried his mother through exile.

Ouedraogo, who would become the first king of the Mossi.

History or myth?

You won’t find Yennenga in the imperial archives of Mali. No medieval Arab chronicler mentions her. Not a word from Ibn Battûta. No ink. Only voices.

What we know of her comes from oral transmission: griots, customary chiefs, family traditions. Memory here is not a library—it’s a living skin, a drumbeat passed down from one generation to the next. But like all oral traditions, it shifts, it adapts, it reinvents.

Yennenga is less a historical fact than an act of collective storytelling. A way for a people—the Mossi—to say:

“This is where we come from. This is what we owe a woman.”

And that claim is not trivial.

In founding stories, Africa is often stripped of mothers. Great empires? Founded by warriors. Cities? By kings. Peoples? By conquerors. And yet… here, a woman births a dynasty.

From Ouedraogo to Ouagadougou

Yennenga did not just bear a son. She founded a lineage. According to tradition, Ouedraogo—born of her union with Rialé—became the first Naaba, the founding chief of the Mossi kingdom. From him descended a line of rulers that would shape one of the most enduring political structures in West African history: the Mossi kingdoms.

Organized around cities like Tenkodogo, Yatenga, and Ouagadougou, these kingdoms quickly developed centralized administrations, complex social hierarchies, and a distinct political culture. Power was monarchic but bound by precise customary rules. The title of Naaba was not only inherited by blood—it had to be validated by community consensus and ancestral lineages.

The child’s name—Ouedraogo, meaning “male stallion”—was no accident. It embodied the fusion of Yennenga’s heritage as a horsewoman and the vigor of a coming lineage. Ouedraogo became the symbol of political continuity, while his mother embodied the break. Through him, the story shifted from myth to governance.

To this day, Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, draws its name from this legacy. The royal palace of the Naabas remains a symbolic and political center. One cannot understand the Burkinabè imaginary without grasping the place of this dynasty—resistant to raids, Mandingue conquests, colonial pressures—and still representing a form of identity-rooted stability.

Yet this legacy is not frozen. It is alive, transmitted, and debated. Yennenga is not just a name etched in state speeches or history textbooks: she is the origin of a nation that still reflects upon her. Every statue of her, every square, every festival bearing her name reaffirms this truth: at the dawn of the Mossi people stood a woman, a horsewoman, a transgression.

Yennenga in postcolonial Burkina Faso

Yennenga did not remain buried in the dust of legend. In Burkina Faso, her image has been patiently sculpted, reclaimed, and elevated as a national symbol. She is everywhere—on currency, in street names, schoolbooks, and especially in the eyes of Burkinabè who grew up believing their history began with a woman.

At the heart of this modern revival stands one major symbolic event: FESPACO. This Pan-African film festival—one of the continent’s most prestigious—grants its top award, the “Étalon d’Or de Yennenga” (Yennenga’s Golden Stallion), to the film judged most representative of Africa. This is no accident. The trophy is a horse—tall, proud, like the one that carried the horsewoman across Dagomba’s borders. It is not just about honoring a film, but affirming a worldview: an Africa in motion, in creation, in search of memory and meaning.

Yennenga’s image was also politically embraced in post-independence Burkina Faso, notably under Thomas Sankara. The revolutionary leader, champion of sovereignty, women’s emancipation, and cultural reclamation, saw in Yennenga an ideal figure—rooted in tradition yet rebellious, African yet universal, woman yet founder. Under his leadership, the image of the horsewoman became a model—for girls, for soldiers, for the people. She became not only a heroine but an ideal to strive for.

Yet this sanctification, however powerful, is not without ambiguity. Through repeated political use, Yennenga risks being frozen as a national mascot, stripped of her complexity. She is elevated, quoted, but also reduced. The rebel becomes a statue; the runaway becomes a matron. She sometimes ceases to be a woman and becomes only an image.

And yet, beyond the political uses and official rhetoric, her name still lives on—through songs, through elders’ tales, through street graffiti, through the names given to daughters. A popular, flexible, sincere memory reminding us that before she became a figure of state, Yennenga was a story of love, of choice, of defiance. A story that resonates because it is both distant and intimate. An African story—but also a human one.

Why tell Yennenga’s story today?

Why, a thousand years later, still talk about Yennenga? Why reflect on a horsewoman whose exact birthdate is unknown, whose name appears in no ancient manuscript, whose life blends with legend?

Because myths are compasses.

Because in a world that has so often denied African peoples their right to history, to greatness, to complexity, figures like Yennenga remind us that Africa has its own origins, its own heroines, its own ways of telling beginnings.

To tell Yennenga’s story today is not to seek archaeological truth. It is to make a political gesture. To recognize that orality, songs, spoken genealogies, and bedtime stories are also archives. To reject the idea that African knowledge must be limited to what colonizers deemed worthy of writing down.

It is also to question what we do, collectively, with our heroines. Do we fix them in bronze? Or do we let them live, speak, challenge? Yennenga today can be more than a name on a trophy. She can be an active principle: the courage to disobey, the audacity to love beyond norms, the power to create a new world from exile.

In an Africa seeking its bearings, fighting for cultural sovereignty, where women’s stories still struggle for visibility without being co-opted or aestheticized, Yennenga is a mirror.

She looks at us. She challenges us.

She tells us that freedom is not always passed down by arms or thrones—but sometimes… by a woman who chooses to ride away.

Sources

- Ki-Zerbo, Joseph, Histoire de l’Afrique noire : d’hier à demain, Hatier, 1972.

- Herskovits, Melville J., Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom, Northwestern University Press, 1938.

- Maquet, Jacques, La pensée africaine, UNESCO, 1971.

Summary

- The Epic of a Horsewoman

- Dagomba, the Kingdom Before Borders

- The Legend of Yennenga

- History or Myth?

- From Ouedraogo to Ouagadougou

- Yennenga in Postcolonial Burkina Faso

- Why Tell Yennenga’s Story Today?

- Sources