Often reduced to a slave uprising, the Haitian Revolution was in fact a political, military, and cultural war of unprecedented magnitude. From 1791 to 1804, it pitted enslaved Africans—turned strategists—against the greatest imperial powers of the 18th century. As the first victorious Black revolution in modern history, it profoundly disrupted the global colonial order, imposing by force the sovereignty of a people whom the West refused to acknowledge as human.

Nofi offers an in-depth exploration of the internal dynamics, political fractures, and geostrategic ambitions of an event still too often marginalized in traditional historical narratives.

At the end of the 18th century, the Western world was in upheaval. Europe, torn between Enlightenment ideals and absolutist regimes, was undergoing major political shifts: the French Revolution shook the monarchical and philosophical foundations of the Old Continent, while newly independent America became a republican experiment. But beyond the European capitals and North American colonies, another, far more radical and subversive center of insurrection arose in the Caribbean. It was Saint-Domingue (the sugar jewel of the French colonial empire), poised to upend the world order.

In this hyper-profitable colony—the world’s leading exporter of sugar and coffee—prosperity statistics concealed a deeply fractured social structure. Beneath the opulence of colonial estates, nearly 500,000 African slaves were held under a regime of regulated terror. Yet this system, built on the erasure of Black humanity, carried the seeds of its own demise. Far from being passive beasts of burden, the enslaved preserved knowledge, networks, a distinct spirituality, and, most importantly, a political memory that would soon erupt into full-scale confrontation.

The Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, far exceeds the notion of a mere revolt by oppressed slaves. It was not a cry of pain, but a strategic, deliberate response, led by Afro-descendant actors determined to forge their own sovereignty. It was the only 18th-century revolution in which the ideals of liberty were seized by those who had been denied even basic humanity. This uprising was not a marginal echo of the French Revolution but an original matrix of Black self-determination, rooted in African conceptions of power, land, and alliance.

This revolt—become revolution, then state—is what Nofi seeks to reexamine from the perspective of free men and women.

I. SAINT-DOMINGUE BEFORE THE STORM

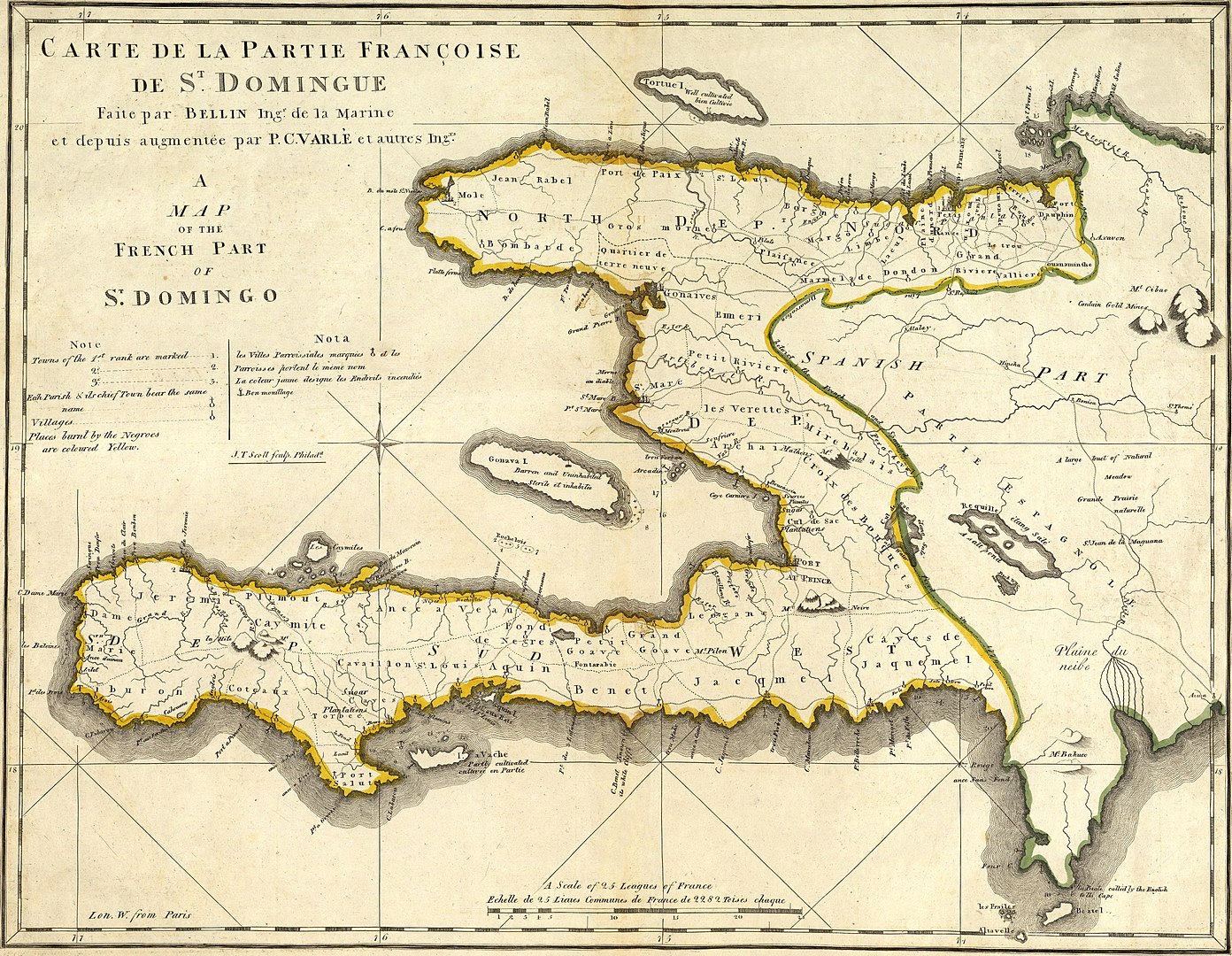

A. A hypercharged colony: Wealth, dependencies, and fractures

In 1789, Saint-Domingue was not just another colony: it was the epicenter of the French colonial economy. Its agricultural output was so massive that a third of the metropole’s foreign trade depended directly on it. The ports of Nantes, Bordeaux, and La Rochelle pulsed with the shipments of sugar, coffee, cotton, and indigo produced on the island’s plantations. Saint-Domingue was an “open-air factory,” designed for export—a beating heart of Atlantic mercantile capitalism.

This model relied on an almost military organization of labor: the plantation, or habitation. Each estate operated as a totalitarian microcosm, ruled by a master, enforced by often-coerced Black overseers, and fueled by a constant influx of African labor. The system survived only through methodical repression and perpetual bodily replacement: a slave’s life expectancy rarely exceeded ten years. Planters, obsessed with profitability, preferred importing over breeding.

At the top of the social pyramid were the “grands blancs”—aristocrats or major merchants—living in the illusion of tropical absolutism. They amassed colossal fortunes, eyed political autonomy, and disdained the nascent Republic in Paris. The “petits blancs,” a motley group of artisans, soldiers, and lower-level civil servants, were frustrated at being poor among the powerful. Their social resentment often manifested as racial hatred, especially toward free people of color—mulattoes or freed Blacks—who were sometimes wealthy, yet systematically excluded from military ranks, honors, and citizenship. These free Blacks embodied a disturbing anomaly in the colonial racial order: educated, property-owning Blacks, sometimes richer than whites.

And at the bottom of the scale lay the silent majority: African slaves. Reduced to movable property under the Black Code (Code Noir), they were supposed to be invisible, obedient, mute. Yet this apparent silence was deceptive. Beneath the whippings and the prayers, in the work songs and ritual vigils, a coded language, an underground memory, and a tenacious identity were being woven. The enslaved were not passive; they watched, whispered, waited. And one day, they would strike.

B. Marronage, Vodou, counter-societies: Seeds of a parallel power

Behind the facade of a solid and efficient colonial order, Saint-Domingue hid a thicket of resistance, escapes, and reinvention. Far from being entirely crushed by the machinery of slavery, enslaved Africans organized durable forms of dissent—often invisible to the master, but symbolically and communally potent. Marronage (escaping slavery) was more than a personal flight—it was a political act, a refusal to exist within the colonial framework.

The marron (runaway who formed communities in the hills or forests) became the foundational figure of Black sovereignty. These fugitive enclaves—sometimes lasting, sometimes fleeting—served as sanctuaries, hideouts, attack bases, and cultural bastions. They revived African lineage structures, warrior chieftaincies, rituals, languages, music, and medicinal knowledge transplanted from the mother continent. Marronage was not just survival—it was a declaration of independence.

At the heart of this autonomy lay Vodou, an Afro-Caribbean religious system long caricatured by missionaries and colonial narratives as barbaric superstition. In reality, it functioned as a spiritual and political institution, weaving together fragments of West African cosmologies (Yoruba, Fon, Kongo) into a theology of connection, covenant, and revolt. Vodou was language, medicine, law, and memory. It enabled communication between the living and ancestors, between the African past and the land of exile.

This religion, centered around lwa (spirits), structured solidarity among slaves from different ethnic groups and created a mental space of freedom. It also served as a tool of organization: the famous Bois-Caïman ceremony in 1791 was precisely a Vodou ritual—both a sacred oath and a call to insurrection.

In the face of this emerging Black culture, the official Catholic Church proved powerless. Staffed by absentee priests, ignorant of Creole and indifferent to Black suffering, the colonizer’s religion faced a dual resistance: on one hand, popular indifference; on the other, active syncretism. Slaves didn’t necessarily reject Catholicism—they reshaped it: saints became masks for lwa, Latin prayers fused with African chants, crosses found homes in Vodou houmforts (temples).

In short, long before 1791, another Saint-Domingue was forming in the shadows: a mental, ritual, symbolic territory preparing the ground for a revolution imagined from the margins. The coming uprising would not fall from the sky—it would rise from the woods, the dreams, and the drums.

II. 1791: THE WAR BEGINS

A. From Bois-Caïman to the Explosion: Timeline of a First Strategic Offensive

On the night of August 14, 1791, in the wooded heights of Morne-Rouge, a clandestine gathering gave rise to one of the most feared founding acts in colonial history: the Bois-Caïman ceremony. Far from the exotic myth spread by colonial tradition (which portrayed it as a bloody witch’s sabbath), this meeting was, in truth, a war congress—a political conspiracy disguised as a religious ritual. Led by Boukman Dutty, a Vodou priest and freed Jamaican slave, the ceremony sealed an alliance between various enslaved African nations: Mandinka, Kongo, Igbo, Arada. The oath was clear: burn the plantations, eliminate the masters, and overthrow the slave system.

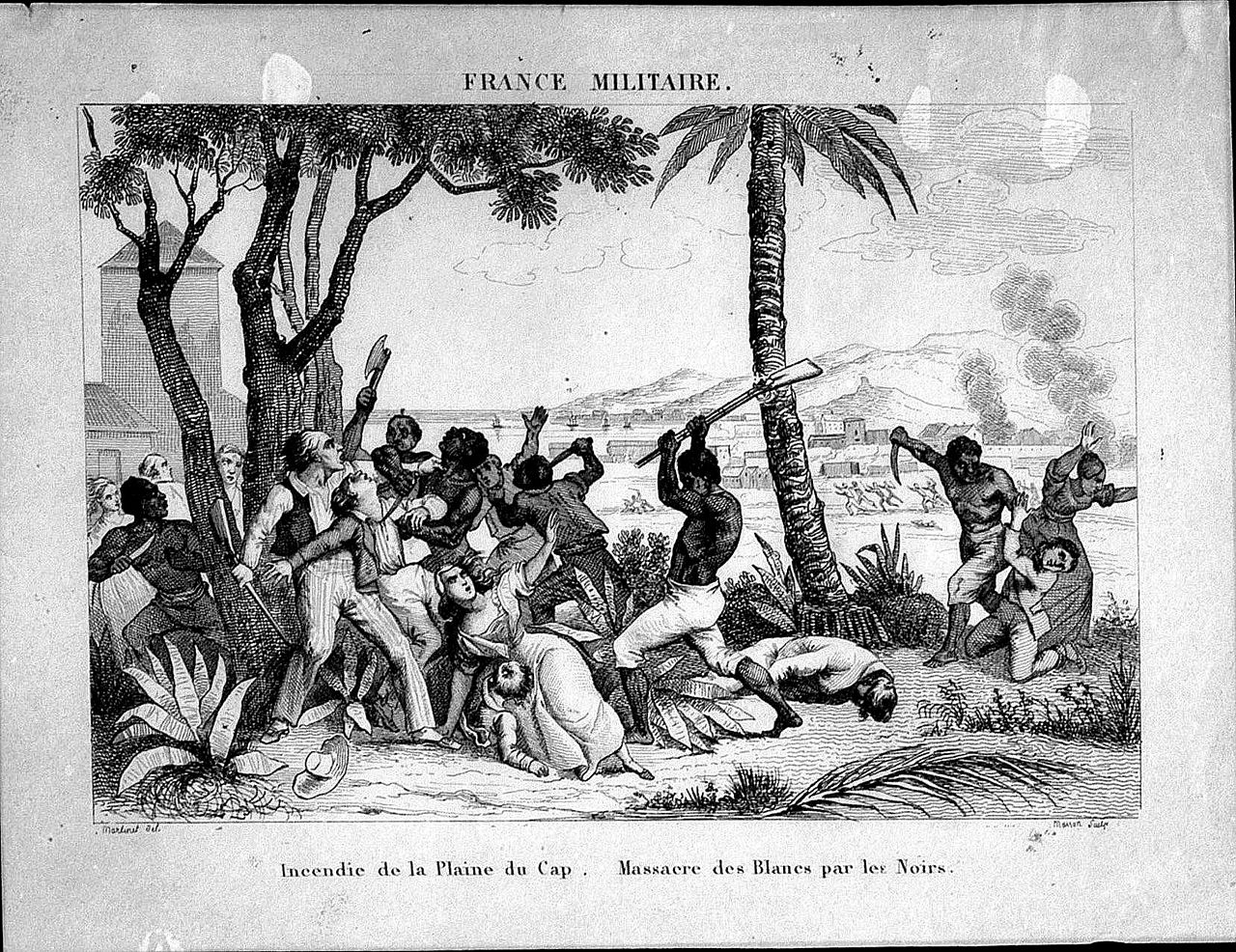

Just days later, the fire was lit. Between August 22 and 23, the colony’s North ignited. In a matter of weeks, nearly 200 plantations were destroyed, hundreds of colonists were killed, and thousands of enslaved people took up arms. This rapid escalation was no accident—it was a coordinated operation, long nurtured in the shadows of slave huts and maroon camps. The insurgent army employed a classic strategy of oppressed peoples: scorched earth, which deprived the enemy of resources and sowed psychological panic.

Three figures emerged during this first phase: Jean-François, Biassou, and Boukman. All were former slaves—often literate or trained within the colonial military apparatus—and led the insurgent forces in an organized, hierarchical fashion. Jean-François proclaimed himself “commander-in-chief” and quickly negotiated with the Spanish in eastern Santo Domingo, who saw in the revolt a chance to weaken France. Biassou established a sustainable logistical base and enforced strict wartime discipline. Boukman, charismatic yet radical, was killed as early as November 1791; his head was displayed publicly in a vain attempt to demoralize the movement.

The insurrection’s impact on colonial and metropolitan opinion was immediate: a political earthquake. In Paris, debates in the Legislative Assembly grew tense, abolitionist groups like the Society of the Friends of the Blacks were marginalized, and it became apparent that the “colonial question” might destabilize the fledgling Republic. In Saint-Domingue, colonists panicked, armed themselves, and demanded aid from the metropole. The illusion of eternal slavery collapsed within weeks.

But what the colonists failed to understand was that this revolt did not merely aim to correct abuses. It was not a call for reform. What the insurgents demanded was the complete destruction of the plantation system and, beyond that, the establishment of an order in which Black people (and they alone) would decide their future. In this sense, 1791 was not an anarchic explosion—it was the first act of a Black national liberation war.

B. Colonial Retaliation and the Entry of European Powers: Toward a Geopolitical Arms Race

Faced with the colony in flames, the French reaction—initially hesitant—quickly turned into a political and military inferno. Colonists demanded reinforcements; the metropole dispatched civil commissioners. But the damage was done: the insurrection had fractured white authority, and revolutionary France—embroiled in its own civil and foreign wars—struggled to form a coherent position on the “Black question.” Into this strategic void stepped two opportunistic powers: Spain and Britain—both still slaveholding, but eager to exploit the revolt to weaken France.

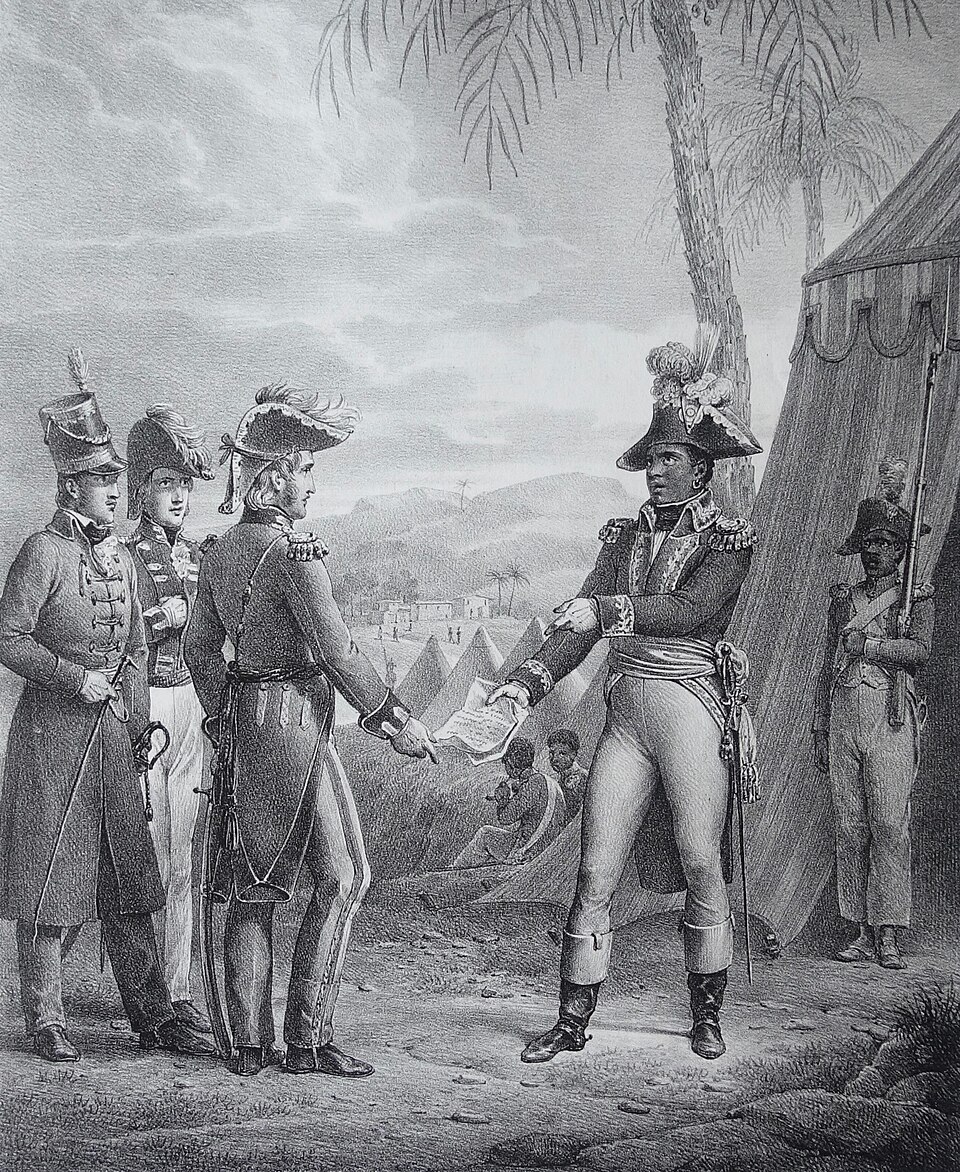

Spain, which controlled the eastern half of the island (Santo Domingo), swiftly adopted a conciliatory tactical approach. Madrid recognized that Black leaders (Jean-François, Biassou, and later Toussaint Louverture) could become valuable military allies in the war against Republican France. In 1793, Spain offered them weapons, ammunition, and official recognition of their military ranks in exchange for their allegiance against the French Republic. This was a pivotal turning point: part of the Black insurgents became an auxiliary army of the Spanish monarchy, adding a transatlantic geopolitical dimension to an already explosive conflict.

The British, for their part, landed in the South in 1793. Officially, their goal was to restore order and protect colonists. In reality, Britain hoped to annex Saint-Domingue—or at least control its ports and production. Royalist planters eagerly opened their doors, hoping to preserve their properties and reinstate the slave system under the British flag. Britain deployed up to 20,000 troops (mostly unacclimated) and quickly ran into harsh realities: disease, Black guerrillas, and sabotage of infrastructure.

This moment ushered in what could be called a geopolitical arms race, where each imperial power sought to manipulate local factions (Black insurgents, free mulatto autonomists, royalist colonists, white Republicans) for its own benefit. But this was a war with inverted rules: Africans, long treated as pawns in European rivalries, became active subjects of diplomacy—negotiating, betraying, and switching alliances based on the realities on the ground. Toussaint Louverture, in particular, would master this art of strategic double loyalty.

Thus, the Haitian Revolution was not merely a war of liberation. As early as 1793, it became a global battle embedded in the broader imperial struggle between European monarchies and emerging republics. And at the heart of this melee, it was no longer the whites who dictated the rules of the game.

III. TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE: THE POLITICAL AND MILITARY GENIUS OF AN AFRICAN LIBERATOR

A. The Man, His Training, and His Network: African Origins and the Art of Negotiation

Among the major figures of modern history, few like Toussaint Louverture managed to transform a peripheral insurrection into a fully-fledged state project. Born a slave around 1743 on the Bréda plantation in the Cap-Français plain, Toussaint was neither a charismatic leader like Boukman nor a military nobleman from Europe. He was something more complex, more formidable: a self-taught strategist, nurtured by African knowledge, French literature, and a quasi-prophetic political instinct.

His origins are the subject of many accounts. One oral tradition (carefully maintained by Toussaint himself) claims noble African ancestry, possibly Arada or Dahomean—a son of a chieftain captured in a slave raid. Whether this was true or not mattered little: the myth of African royalty was no coincidence. It served as a form of legitimacy in a society where the memory of Africa remained structuring, even in exile. Through this lineage, Toussaint situated himself in an ancestral chain of command, re-sacralizing the role of leader within the Black community.

Initially trained as a healer and coachman on the plantation, Toussaint distinguished himself through an uncommon intellectual curiosity. He learned to read and write late, but quickly mastered French, Creole, liturgical Latin, and the great Enlightenment texts: Abbé Raynal, Rousseau, and military strategy treatises. He surrounded himself with former slaves, educated mulattoes, refractory priests, and even ex-colonists. He built a cross-sectional network grounded in competence, loyalty, and realpolitik.

What made Louverture unique was not just his military brilliance, but his ability to handle contradiction: Catholic, yet tolerant of Vodou; Black, yet in dialogue with white colonists; former slave, yet defender of a form of quasi-feudal discipline. He embodied the figure most feared by Europeans: the African who understood the master’s codes without abandoning his own.

Politically, Toussaint developed an early and refined art of negotiation. He switched sides several times (allying with the Spanish until 1794, then siding with the French when the Republic abolished slavery), not out of pure opportunism but as a strategic reading of power dynamics. He understood that real emancipation would not come from Catholic kings or abolitionist Girondins but through autonomy forged in fire and compromise. Each time, he negotiated from a position of strength—demanding recognition of his rank, respect for his men, and guarantees for a new order.

In short, Toussaint Louverture was not just a remarkable Black leader—he was one of the few 18th-century leaders (regardless of origin) who successfully turned a social revolution into an autonomous state project, without succumbing to fantasies of vengeance or subordination to imperial powers. At this point in history, he embodied the political intelligence of the African diaspora in action.

B. A Three-pronged strategy: Diplomacy, terror, economic order

Behind Toussaint Louverture’s charismatic aura lay a rigorous political architecture structured around three pillars: diplomacy, terror, and coercive economic reconstruction. This austere but effective triad allowed Louverture to stabilize a war-torn territory, confront major imperial powers, and impose a form of autonomous Black statehood—albeit at the cost of rising tensions with allies and the peasantry.

Diplomatically, Toussaint played a multidimensional chess game. He exploited Franco-British rivalries, Spanish hesitations, and internal fractures between metropolitan Republicans and royalist colonists. He presented himself as a loyal servant of the French Republic, while consolidating local power. He also wielded strategic betrayal as a tool of sovereignty. He eliminated rivals as needed: Rigaud (leader of the mulattoes in the South) was defeated in 1800, Biassou was sidelined, and even Moyse Louverture—his own nephew—was executed for insubordination. Loyalty was demanded without compromise, even at the cost of familial blood. Order prevailed over sentiment.

Domestically, Louverture understood that political freedom was meaningless without economic survival. After years of war, plantations lay abandoned, and former slaves (now free) often refused to return. Louverture imposed a system of mandatory labor, close to state serfdom: former slaves had to return to plantations under military supervision, paid a fixed wage. White planters were invited back, protected by Black soldiers, in a strange and tense pact. This choice—criticized even in his time—was seen by some as a betrayal of emancipation ideals. But for Louverture, it was a necessary evil: he had to prove to Europe that Saint-Domingue could remain a credible commercial actor—even without slavery.

Finally, in 1801, Louverture crossed a decisive threshold: he promulgated a unilateral Constitution, written without approval from Paris, appointing himself governor for life with the right to name his successor. This Constitution, while confirming the permanent abolition of slavery, also declared Catholicism the state religion and centralized all power in Louverture’s hands. Some saw it as a “Black Bonapartist” moment—an authoritarian, personal power based on order, leadership cult, and legitimacy forged in war. Others viewed it as the only viable structure, in a hostile world, for preserving freedom won through arms.

In any case, this inflexible yet visionary strategy made Toussaint not a saint, but the founder of a modern Black state—full of contradictions, able to navigate between the necessities of war and the demands of a fractured society.

IV. WAR AMONG BLACKS: DIFFERENT WAYS OF BEING FREE AMONG AFRO-CREOLES

A. Dessalines, Christophe, Rigaud, Pétion: The North/South Divide

The Haitian Revolution, long portrayed as a straightforward clash between Blacks and whites, actually contained a more subtle and painful dimension: a war among Black factions themselves. For once the slaveholding enemy had been weakened, the next question emerged: how should freedom be lived? And more crucially, who gets to define it?

Here is where the major post-1799 figures confronted each other:

- Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the radical right-hand man of Louverture,

- Henri Christophe, a rigid military modernist,

- André Rigaud, a republican mulatto loyal to the class of free people of color,

- Alexandre Pétion, a learned Creole advocating a more liberal order.

These men did not only clash militarily; they represented four competing visions of Black freedom, shaped by social background, skin color, and political ambition.

The North/South divide crystallized in 1799 during what would later be called the “War of the Knives.” Rigaud, backed by the mulatto elite in the South, rejected the growing dominance of Black northerners in positions of power. Under the guise of a republican struggle, he waged war against Toussaint Louverture, who responded with a brutal campaign, particularly executed by Dessalines. Though often downplayed in official narratives, this was a racial civil war, driven by old resentments: the mulatto elite’s contempt for African-born Blacks, and freedmen’s distrust of affranchis often complicit in the plantation regime.

Dessalines, the ultimate Black figure with no ties to France, was the archetype of the radical popular leader. He despised the mulatto elites, whom he viewed as a disguised colonial bourgeoisie. For him, freedom meant the complete eradication of the old order, including its Creole intermediaries. Christophe, more austere, envisioned a hierarchical Black society modeled on European (almost Prussian) discipline. Rigaud dreamed of a republican Haiti governed by an enlightened elite—mostly mixed-race, Francophone, educated—replicating the colonial social structure without slavery. Pétion vacillated between liberal idealism and clientelist pragmatism, later instituting a system of small landholding for stability while keeping power in the hands of a narrow ruling circle.

Beneath these conflicts lay a fundamental unresolved question of the revolution:

Was freedom a total rupture with the colonial world, or could it accommodate an inverted replica of the same system? And most importantly:

Who were the legitimate heirs of that freedom? The former slaves? The freedmen? The Creole intellectuals? The victorious generals?

Thus, the war among Blacks was not an afterthought but a second, more silent, more painful revolution, in which the Black population had to learn that freedom was not enough—one had to organize it, share it, and sometimes enforce it.

B. The War of the Knives: Weapons of Discord

The War of the Knives (1799–1800) was far more than a simple military clash between rival factions. It marked a historic rupture—the moment internal fault lines within post-slavery Black society exploded into plain view. In this internal struggle, the South and North were not just geographical zones: they symbolized opposing visions for Haiti’s future, distinct cultural heritages, and differing understandings of Black identity and colonial memory.

The South, dominated by mulatto elites like Rigaud, was more Francophile, urban, and aligned with metropolitan republican values. Its social order remained steeped in color hierarchies: though Blacks were numerous, the ruling class—freed before 1791—sought to maintain supremacy. This elite feared the power of the former slaves from the North, whom they viewed as uncultured, brutal, and uncontrollable.

The North, stronghold of former slaves, was the direct heir to the 1791 uprising. Under Louverture, and later Dessalines and Christophe, it was organized as a militarized, agrarian zone marked by discipline, forced labor, and the ambition to build Black political autonomy based on authority rather than parliamentary debate. It was also more open to Vodou and African memory—elements regarded with scorn or concern by the Southern republicans.

The war began in June 1799 when Louverture—under the pretext of restoring republican order—launched an offensive against Rigaud. In reality, it was a campaign of political and racial cleansing, aimed at breaking mulatto hegemony over the southern cities. Dessalines led this operation with calculated ferocity. Atrocities abounded; summary executions multiplied. On the other side, Rigaud’s forces—quietly supported by metropolitan Frenchmen hostile to Louverture—also carried out targeted repression against Northern Black officers.

Amid this explosive context, lesser-known but crucial figures emerged:

- Lamour Desrances, an independent Black leader in the West,

- Moyse Louverture, the governor’s own nephew.

Both embodied internal dissent—not from the mulatto enemy, but from within the Black base itself. Moyse, notably, criticized the return to forced labor and the retention of white planters. In October 1801, he led a popular revolt against his uncle. Louverture, loyal to his sense of order, had him arrested and publicly executed. This act broke a taboo: the Revolution was now devouring its own, even the closest.

Lamour Desrances led an autonomist guerrilla campaign around Port-au-Prince, rejecting Louverture’s central authority. Though he failed militarily, his resistance revealed a deeper truth: even within the Black camp, unity was a fragile illusion. There were divisions of class, memory, and strategy. Not all Blacks wanted the same future—some demanded local autonomy, others agrarian reform, others a disciplined Black monarchy.

Thus, the War of the Knives was a war of visions, not just generals. It foreshadowed the post-independence fractures that would split Black unity between two poles:

- Cap-Haïtien, the stronghold of Christophe’s Black kingdom,

- Port-au-Prince, Pétion’s mulatto republican capital.

The Black sword of liberty was slowly turning inward—no longer to break the master’s chains, but to sever alliances among former brothers-in-arms.

V. NAPOLEON AND THE FRENCH EXPEDITION: TOTAL WAR

A. Leclerc, Rochambeau, and the Logic of Extermination

In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul, decided to put an end to the Haitian project of Black autonomy. Under the guise of restoring republican order, he sent to Saint-Domingue the largest colonial expedition ever launched by France: nearly 30,000 men, led by his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc. The unofficial objective was clear: overthrow Toussaint Louverture, disarm the Black population, and reinstate slavery—as had already been done in Guadeloupe.

From the outset, the French troops employed a double strategy: on one hand, political seduction—promising that freedom would be maintained, initiating talks with Black leaders; on the other, military terror—roving columns, preemptive massacres, and systematic harassment of Haitian positions. At first, Toussaint attempted conventional military resistance, but faced with France’s logistical superiority, he shifted to guerrilla tactics: burning crops, sabotaging roads, setting ambushes in the hills.

But the turning point came with internal betrayal: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and later Henri Christophe pretended to ally with Leclerc. This maneuver, more tactical than sincere, disoriented Toussaint, who eventually surrendered in May 1802 in exchange for a promise of safety. That promise was broken: Toussaint was arrested and deported to France. Imprisoned in Fort de Joux, in the Jura, he died months later, in April 1803. Before leaving, he reportedly uttered a prophetic warning:

“By overthrowing me, you have only cut down the trunk of the tree of liberty. It will spring back from the roots, for they are deep and numerous.”

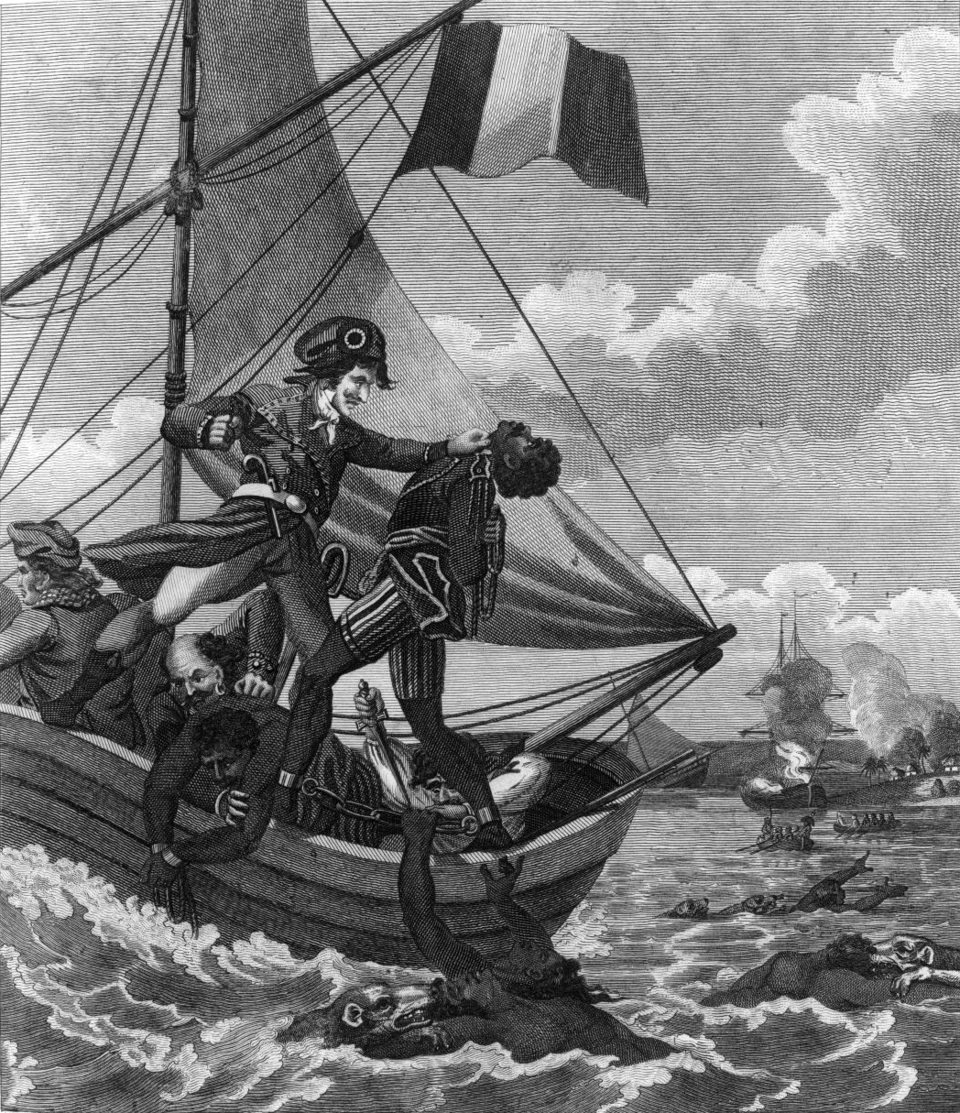

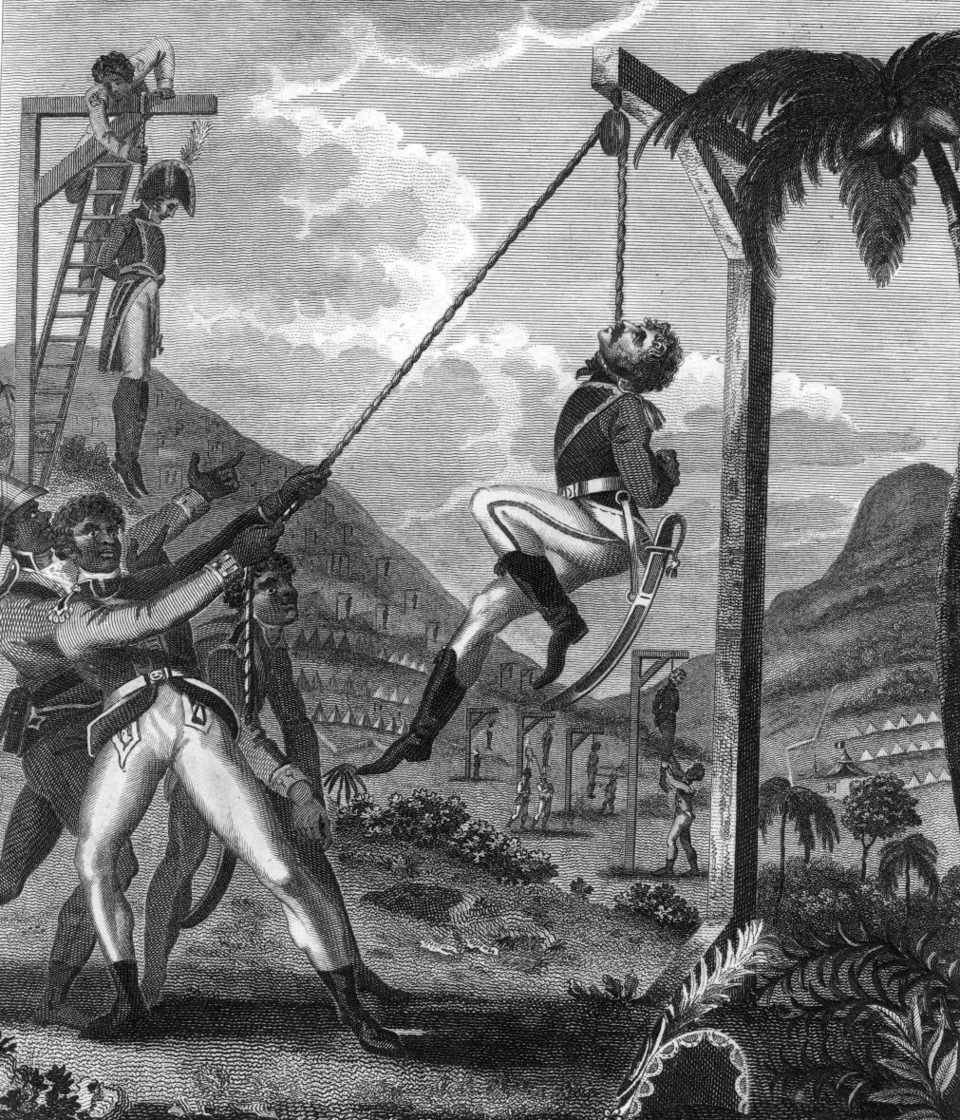

With Louverture’s disappearance, the French believed they had pacified the island. But resistance reorganized, and colonial strategy then descended into horror. Leclerc, increasingly isolated and paranoid, died of typhus in November 1802. He was replaced by Donatien de Rochambeau, a ruthless officer who launched an almost openly racial extermination campaign. The orders were clear: no mercy. Captured Blacks were hanged, drowned, or burned alive. Rochambeau even devised rudimentary chemical methods, locking prisoners in ship holds and filling them with toxic smoke. Women, children, the elderly—none were spared. Suspected rebels were buried alive, wells were poisoned, entire countrysides decimated.

Yet far from breaking the population, this logic of terror radicalized resistance. Toussaint’s former allies—Dessalines, Christophe, Pétion—joined forces. Peasants took up arms, women served as spies, children guided fighters through the mountains. The war became total and existential: it was no longer about negotiating a status, but seizing a homeland—or dying.

Within a year, French troops collapsed—ravaged by disease, desertion, and widespread hatred. Surrounded, Rochambeau surrendered in November 1803 after the Battle of Vertières. It wasn’t just a military defeat—it marked the first time in modern history that a European empire was expelled by an army of formerly enslaved people.

B. 1803: The Battle of Vertières, Founding Act of a People of Arms

On November 18, 1803, on the hills of Vertières, a few kilometers from Cap-Français, the final act of the most improbable colonial war unfolded. Facing a weakened but entrenched French army, the Black troops led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines launched a decisive offensive. It was more than a battle: it was a warrior consecration, an armed declaration of a people refusing to return to bondage.

Dessalines, long regarded as Louverture’s brutal enforcer, revealed here his own ruthless and methodical strategic brilliance. He knew the enemy’s weaknesses, habits, and arrogance. He divided his troops into mobile units, struck from the flanks, cut supply lines, and exploited the French army’s moral fatigue. He fired up his soldiers with blazing speeches, invoked the ancestors, and promised land or death. Most of all, he ordered that no symbol of colonial domination be spared.

Facing him, Rochambeau—abandoned by Paris, trapped in a war he no longer understood—held on desperately. His soldiers, ravaged by typhus and crushed by demoralization, were surrounded. Technical superiority was no longer enough against a Black army united by rage, memory, and a thirst for autonomy. Even non-enlisted former slaves provided food, intelligence, and logistical support.

The Battle of Vertières was short, brutal, decisive. General Capois-la-Mort, struck down multiple times by gunfire, kept charging forward shouting “Forward!”—his gesture became legend, the symbol of a freedom stronger than fear. Shaken by this iron determination, Rochambeau surrendered on November 28. He was granted the dignity of leaving the island with his remaining troops, but left behind a destroyed army and a humiliated empire.

Vertières was not just a military victory. It was the first time a slave colony defeated a European great power in a direct and prolonged conflict. It proved that history no longer unfolded only in Paris, London, or Madrid—but also in the hills, cane fields, and stone fortresses of the Black world.

With that victory, the Haitian people were born—baptized in blood and armed sovereignty. It was not a gift, nor a decree from above, but a conquest wrenched by Black men and women who refused to become plantation flesh again. At Vertières, the descendants of Africans torn from their homeland made imperial arrogance bow. That day, world history changed sides.

VI. 1804 AND BEYOND: AN INDEPENDENCE WITHOUT A MODEL

A. The Massacre of the Colonists: Strategic Purification or Historical Burden?

On January 1, 1804, in the public square of Gonaïves, Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed the independence of Haiti—the first free Black republic in the modern world. But barely had the ink dried when one of the most controversial episodes of the Haitian Revolution began: the systematic massacre of the remaining white colonists. Between February and April 1804, between 3,000 and 5,000 French people—men, women, elderly—were killed on Dessalines’s orders. This was not a popular riot nor an uncontrolled outburst of vengeance: it was a coordinated purge, executed zone by zone by officers carrying out a political command.

Dessalines’s justifications were manifold. First, to preserve independence through terror: to prevent any return to slavery and dissuade the French from future landings by erasing their demographic footprint. Second, to avenge the thousands of Black deaths in the war, Rochambeau’s massacres, the hangings, the tortures, the betrayals. Third, to re-found Haitian society on an inverted racial base: Haiti would no longer be a white colony, but a Black nation—unambiguously. In Dessalines’s mind, this brutal logic was strategic, not hateful.

The consequences were immediate: Western outrage exploded. Survivor testimonies fueled a massive racist propaganda campaign across Europe and the Americas. Haiti became a pariah state, whose independence was denied or ignored by the great powers for decades. Only Jefferson’s United States (itself slaveholding) agreed to trade relations—with notorious hypocrisy. The massacre became a historical burden, used to demonize the Haitian experiment and dampen abolitionist enthusiasm elsewhere.

Internally, the colonists’ disappearance left an economic and technical vacuum. Dessalines tried to maintain the plantation economy without slavery: confiscating land, sometimes redistributing it, but mostly imposing mandatory labor—like Louverture before him. The army became the backbone of the state: it supervised, produced, disciplined. Freedom existed, but it was regimented, militarized, policed.

The contradiction was glaring: slavery was abolished, yet forced labor persisted. The white master was gone, but the Black commander replaced him. The nascent Haitian state was caught between radical emancipation and structural dependence on the colonial economic model. The Black people were no longer enslaved—but not yet sovereign over their living conditions.

Thus, the 1804 massacre—both founding act and open wound—summarized the tensions of Haitian independence: between security and brutality, between seized freedom and inherited order, between necessary cleansing and impossible memory. It remains, to this day, the most explosive knot in Haitian consciousness and its global image.

B. Pétion, Christophe, Boyer: The divided heirs

After the assassination of Jean-Jacques Dessalines in October 1806, the Haitian Revolution entered a new phase: political fragmentation. Former comrades-in-arms became heirs to a dream increasingly difficult to uphold—torn between personal ambition, ideological divergence, and the institutional vacuum left by the war. Three figures emerged: Henri Christophe, Alexandre Pétion, and later Jean-Pierre Boyer. Three men, three leadership styles, three visions of what Haiti should become after the rupture.

In the North, Henri Christophe founded an authoritarian, centralized regime. Inspired by European monarchies and Prussian military rigor, he declared himself King Henry I in 1811, established a Haitian nobility, and built palaces worthy of his vision—including the imposing Citadelle Laferrière, a defensive bastion against recolonization. But this dream of a disciplined Black empire rested on a peasant base forced into labor: Christophe imposed a militarized plantation economy based on output and obedience. Architectural and administrative progress came with fierce repression. Order reigned—even at the cost of consent. Isolated and ill, Christophe committed suicide in 1820, abandoned by his officers.

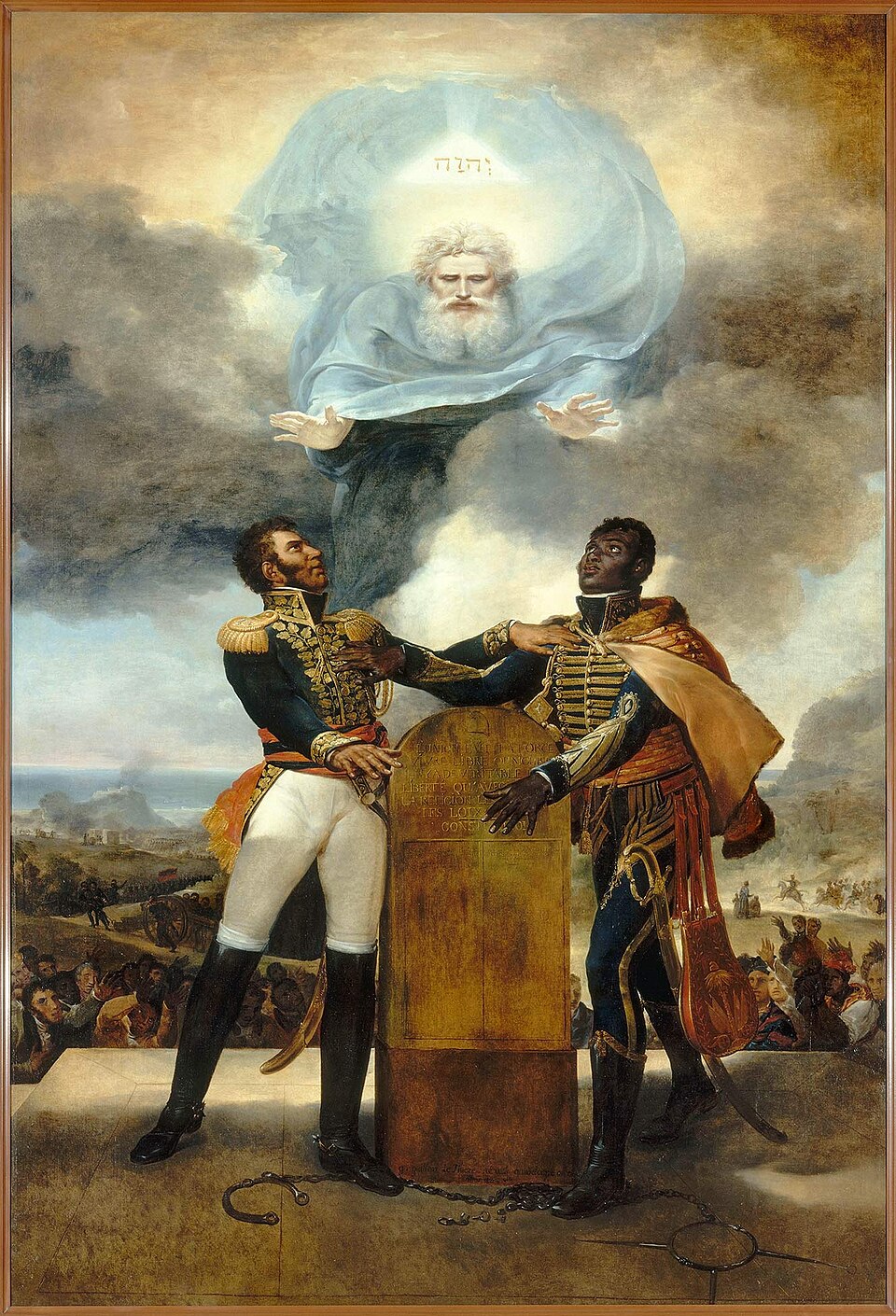

In the South, Alexandre Pétion represented the exact opposite. President-for-life of a Creole republic, he promoted a mulatto democracy rooted in small landholdings. He redistributed state lands to former soldiers and peasants, pursued a liberal but uneven policy: the military and administration remained under the control of a Francophone mixed-race elite, marginalizing rural Black masses. Pétion is praised for supporting Latin American independence movements (notably Simón Bolívar), but his regime entrenched a two-tiered society: surface-level freedom, continued privilege beneath.

Finally, Jean-Pierre Boyer, Pétion’s successor, managed to reunify the country in 1820 and annex the eastern part of the island (now the Dominican Republic). But this newfound unity was soon undermined by a disastrous act: in 1825, under threat of reinvasion, Boyer signed an agreement with monarchist France (Charles X), recognizing Haiti’s independence in exchange for an indemnity of 150 million francs. This exorbitant sum—meant to “compensate” former colonists for the loss of human and material property—crippled Haiti’s economy for over a century. This immoral colonial debt, negotiated under duress, became a financial dogma.

This French obsession, combined with a lack of international support, trapped Haiti in political isolation and structural dependency. Internal divisions, color-based rivalries, clashing governance models—all prevented the emergence of a coherent national project.

Ultimately, the heirs of 1804 failed—or were unable—to transform a revolutionary victory into a lasting and equitable political order. The dream of a Black empire, the mulatto republic, the unified state under economic tutelage: all were unfinished and contradictory paths that would shape Haiti’s 19th-century tensions. Freedom was won in fire—but sovereignty remains to be built.

CONCLUSION

The Haitian Revolution remains, even today, a seismic event in world history—so radical it has no direct equivalent. It is the only slave revolt to have produced a sovereign state governed by those whom the colonial order deemed subhuman. In that sense, Haiti is not only the “first Black republic”: it is the unacknowledged matrix of all modern insurrections, proof that the wretched of the earth can overturn history.

But the revolution was also a burden—for both its actors and their descendants. It bore the paradoxes of a struggle that had to abolish slavery while preserving plantation economics; proclaim liberty while imposing order through coercion; imagine Black sovereignty in a world still structured by white imperialism. The Haitian people inherited an independence with no model—built on ruins, besieged from without, fractured from within.

What makes Haiti unique is not just its victory over Napoleon’s army, nor even its proclamation of a new order—but how it embodies the colonial fracture deep within its society: between African memory and republican aspiration, between Black monarchist dreams and mulatto democratic visions, between radical autonomy and imposed financial dependency.

Haiti has never stopped unsettling the West—not because it failed, but because it dared. It dared to abolish slavery by force, without waiting for the oppressor’s moral awakening. It dared to exist outside European models. It paid the ultimate price for that audacity. Yet in that political tragedy, it left an indelible mark: that of a people standing tall—born of relentless struggle, carrying a universal promise:

freedom, seized—not granted.

Notes and References

- Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Fick, Carolyn E. The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below. University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press, 1995.

- Garrigus, John D. Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in French Saint-Domingue. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Geggus, David P., ed. The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History. Hackett Publishing, 2014.

Summary

I. SAINT-DOMINGUE BEFORE THE STORM

A. A hypercharged colony: wealth, dependencies, and fractures

B. Marronage, Vodou, counter-societies: seeds of a parallel power

II. 1791: THE WAR BEGINS

A. From Bois-Caïman to the explosion: timeline of a first strategic offensive

B. Colonial retaliation and the entry of European powers: toward a geopolitical arms race

III. TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE: THE POLITICAL AND MILITARY GENIUS OF AN AFRICAN LIBERATOR

A. The man, his training, and his network: African origins and the art of negotiation

B. A three-pronged strategy: diplomacy, terror, economic order

IV. WAR AMONG BLACKS: DIFFERENT WAYS OF BEING FREE AMONG AFRO-CREOLES

A. Dessalines, Christophe, Rigaud, Pétion: the North/South divide

B. The War of the Knives: weapons of discord

V. NAPOLEON AND THE FRENCH EXPEDITION: TOTAL WAR

A. Leclerc, Rochambeau, and the logic of extermination

B. 1803: the Battle of Vertières, founding act of a people of arms

VI. 1804 AND BEYOND: AN INDEPENDENCE WITHOUT A MODEL

A. The massacre of the colonists: strategic purification or historical burden?

B. Pétion, Christophe, Boyer: the divided heirs