Little known to the general public, the Siddi community—Africans settled in India and Pakistan for over five centuries—reveals a long-overlooked chapter of Afro-Asian history, marked by kingdoms, Bantu traditions, and military strongholds. A diaspora far removed from a victim-centered narrative.

When the African diaspora is mentioned, attention almost exclusively turns to the Atlantic: slave ships, plantations, and revolts. Yet, another equally ancient and largely ignored chapter unfolds across the Indian Ocean. Far from the Americas, African presence has taken root for over a millennium in the lands of present-day India and Pakistan. These communities, known as Siddis or Sheedis, offer a fascinating counter-narrative to traditional portrayals of victimhood: while many were once enslaved, they also rose as soldiers, administrators, musicians, state builders—and at times, even sultans.

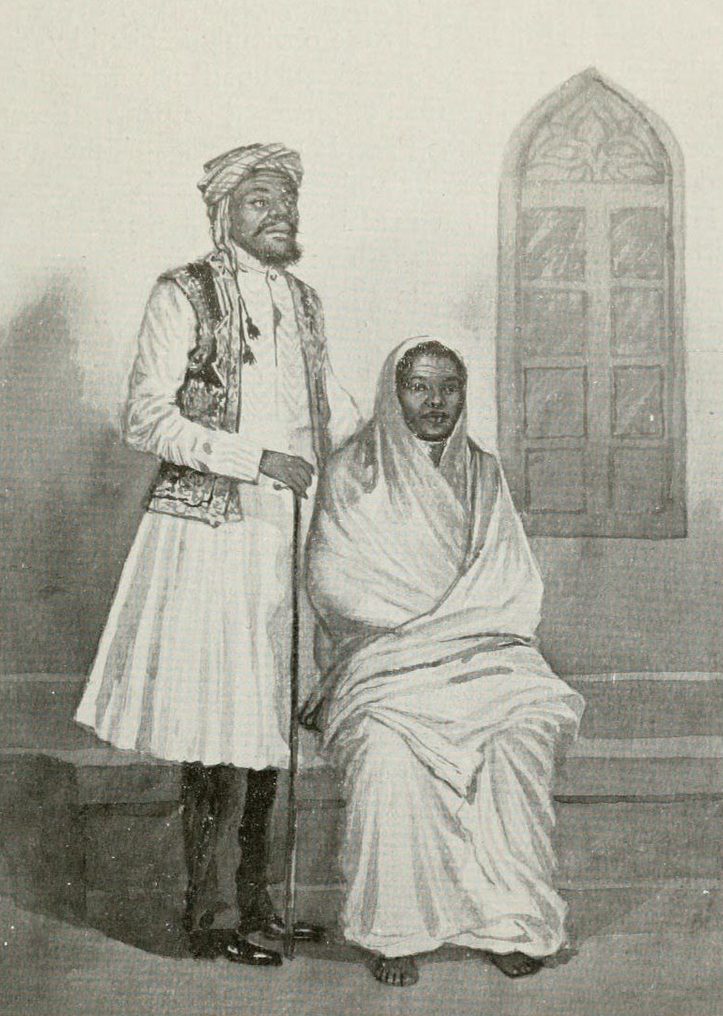

From Malik Ambar, a 16th-century military strategist in the Deccan, to the African guards of the Nizam of Hyderabad, Siddis have left a lasting mark on the political, military, and cultural spheres of the subcontinent. Their journey reflects adaptability, social mobility, and the preservation of African cultural traits, often defying narratives of passive assimilation.

How did these minority, dispersed Afro-descendant communities manage to establish a durable presence in South Asia’s tumultuous history? What social structures, political alliances, or cultural resources enabled them to endure through the centuries? Through the prism of the Siddis, a different geopolitical vision of Africa emerges—one that looks eastward.

I. GENEALOGY AND GEOSTRATEGY OF A MARITIME DIASPORA

1.1 African origins and indian ocean circulation

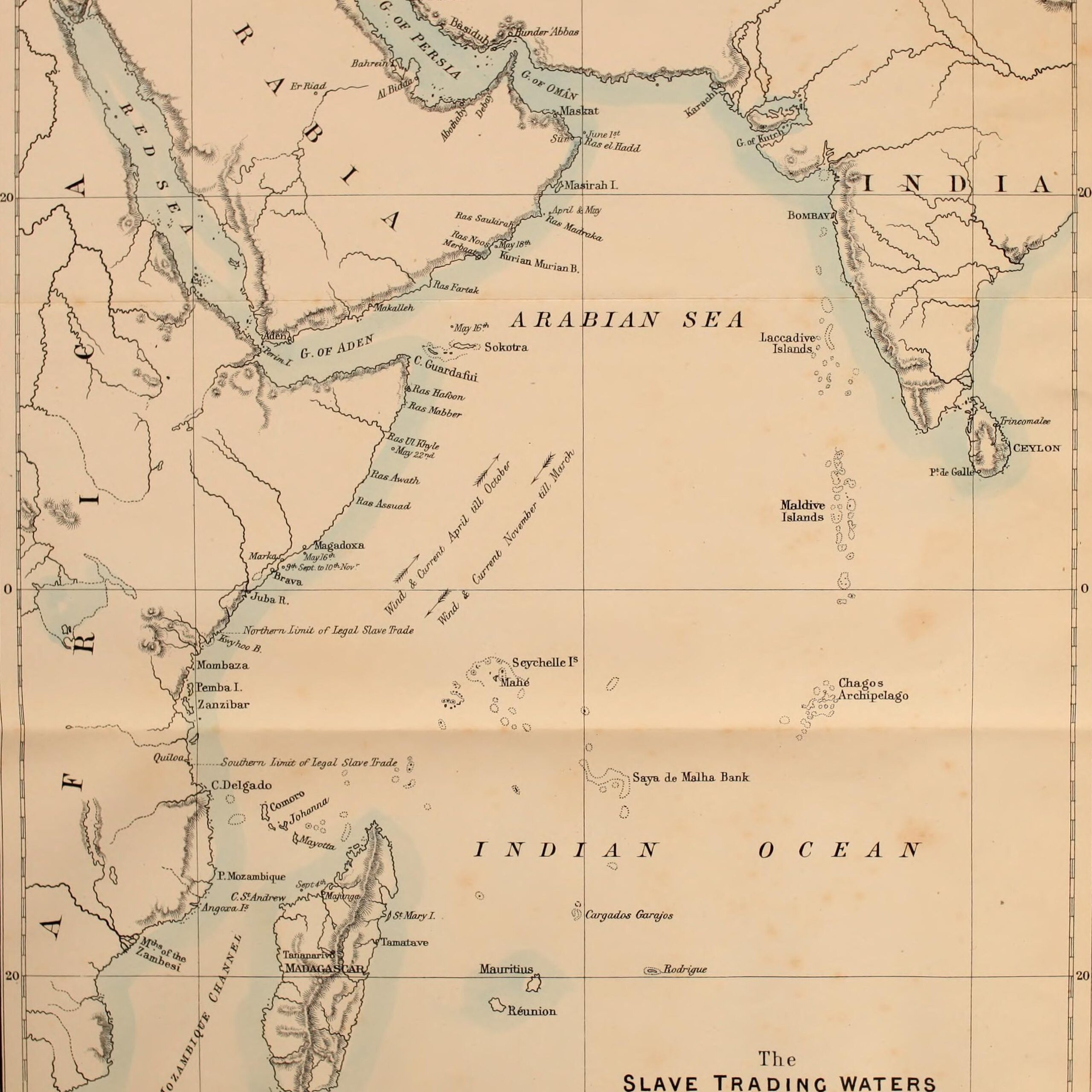

The history of the Siddis spans a vast geography—from the coasts of East Africa to the shores of Gujarat and Sindh. Originating from Bantu regions (from Mozambique to Kenya), as well as the Ethiopian highlands and Abyssinia, these men and women were swept into a centuries-long maritime network linking Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and South Asia. This circulation was not limited to slavery—it also included trade, military migrations, religious alliances, and permanent settlements.

Long before European expansion, the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea already served as key axes of human mobility. Omani merchants, Gujarati sailors, and Arab captains transported Africans—sometimes as slaves, but also as mercenaries or sailors. Arabs referred to them collectively as Zanj, a term for Black peoples of East Africa. These Zanj constituted the first Afro-Asian contingents on the Indian subcontinent—well before Europeans arrived.

When the Portuguese established outposts in Goa and along the Malabar Coast in the 15th century, they were merely inserting themselves into an older dynamic. They too transported Africans from their Mozambican colonies, but under a Christian imperial logic. In short, the Siddis were not sudden outsiders—they were part of a fluid, longstanding Afro-Asian exchange, with the Indian Ocean as its central stage.

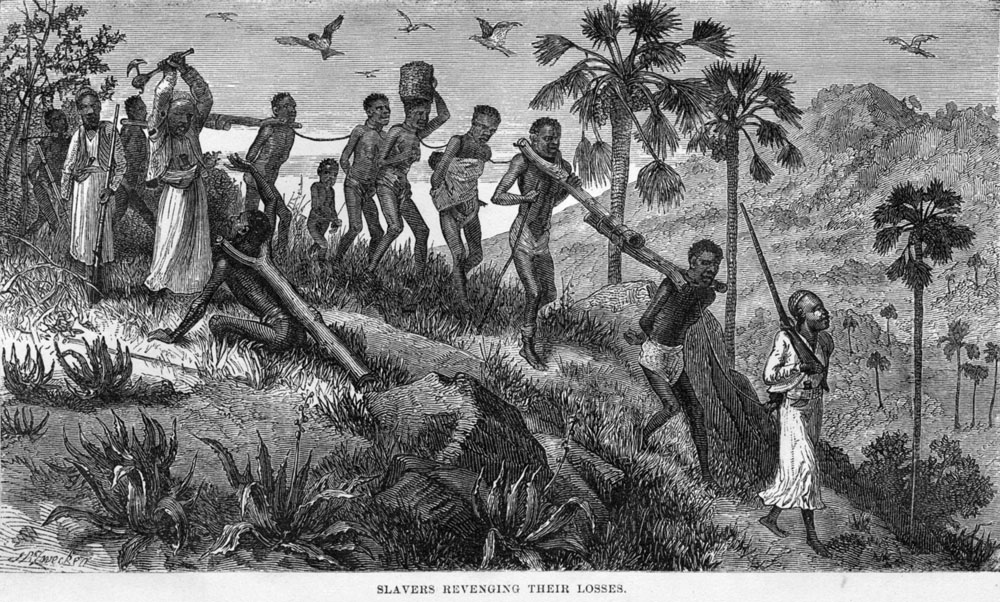

1.2 Multiplicity of statuses: Slaves, soldiers, traders, elites

Reducing Siddi history to slavery alone would mean ignoring their deep political and military involvement on the subcontinent. While many were indeed enslaved (particularly through Omani and Portuguese routes), their destinies were neither fixed nor linear. The social systems of medieval Indian sultanates allowed some captives—once converted or emancipated—to rise to positions of military, administrative, or even sovereign power.

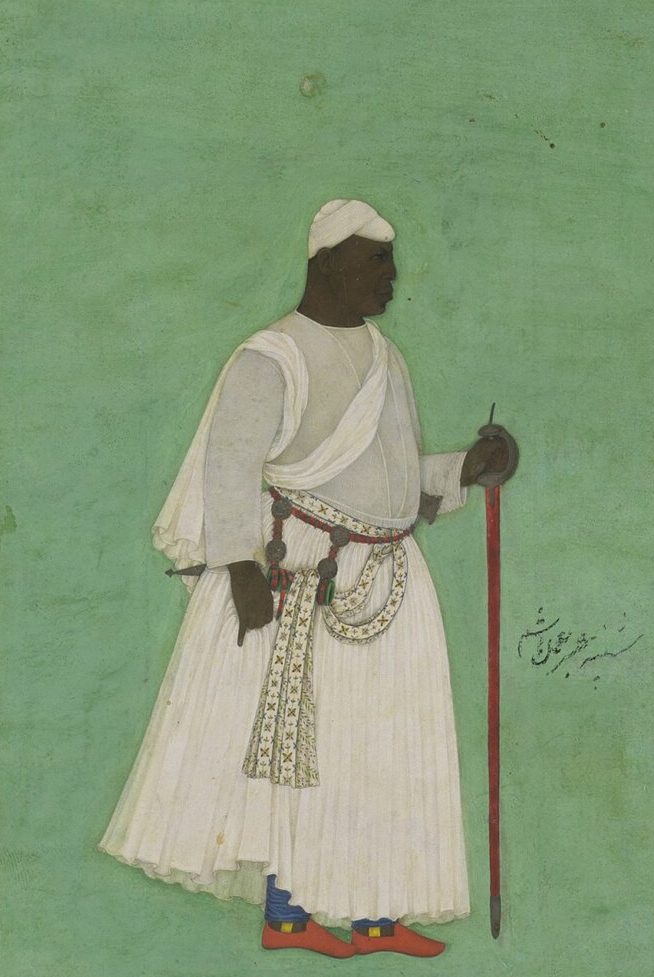

The most illustrious example is Malik Ambar (1548–1626). Born in Ethiopia, captured in childhood, and sold multiple times before being freed, he became one of medieval India’s greatest military strategists. As commander of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate’s army, he employed guerrilla tactics against Mughal incursions, reshaping the balance of power in the Deccan. More than a general, he was a builder: an urban planner, diplomat, and patron of the arts. He founded the city of Aurangabad and commanded the respect of sultans and emperors alike.

But Malik Ambar was not alone. Figures like Ikhlas Khan in Bijapur, Sidi Johar in Murud-Janjira, and Saifuddin Firuz Shah in Bengal show how some Africans turned servitude into real authority. Some even established independent or semi-autonomous states, such as the Siddi principality of Janjira, which fiercely resisted the Marathas.

Siddi society was thus internally stratified—from soldiers to governors, fishermen to courtiers. This diversity of status challenges the notion of a dominated population and instead presents a mobile, politically active social body.

II. REGIONAL SETTLEMENTS AND SOCIOPOLITICAL STRUCTURES

2.1 African States in Asia: Sovereignty and military strongholds

Siddi settlements on the Indian subcontinent were not mere peripheral presences. They also formed political and military power centers, sometimes with remarkable autonomy. This long-term phenomenon, across various regions, counters the idea of a passively assimilated diaspora. Siddis created a political memory rooted in geography and institutions.

The clearest example is the Janjira Fort, off the Konkan coast in today’s Maharashtra. This maritime fortress, held by Siddi dynasties for nearly three centuries, fiercely resisted Maratha naval ambitions. Far from being mere vassals, the Nawabs of Janjira skillfully navigated Mughal, European, and regional rivalries—sometimes aligning with Delhi, other times asserting their own path. Their dynasty’s tombs, preserved weapons, and remaining charters testify to real sovereign power.

In Hyderabad, Africans integrated into the Nizams’ elite cavalry represented another kind of bastion—more military than territorial. These African Horse Guards, stationed near Masjid Rahmania, were valued for their loyalty and unique culture, centered around marfa music of Afro-Arab origin. The neighborhood of Habsiguda, literally “village of the Habshis,” preserves toponymic memory of this institutionalized African presence.

Further east in Bengal, the 15th century saw the rise of a brief but notable Habshi dynasty. Amid political crisis, Abyssinian-origin slaves promoted to officers by Bengali sultans seized power by force. Saifuddin Firuz Shah, builder of the Firoz Minar in Gour, symbolizes this fleeting dominance. Rather than a folkloric footnote, this episode reveals how porous ethnic and social hierarchies were within sultanate structures.

These African strongholds—whether naval, military, or dynastic—map an unexpected geography of Siddi power in Asia. Despite their dispersal, Africans in India and Pakistan were, at times, sovereign agents and state-builders.

2.2 Rural and sedentary Siddis

Beyond military leaders and autonomous bastions, the majority of Siddis gradually settled into rural life. Scattered across western and southern Indian states (Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Goa) and Pakistani provinces (Sindh, Balochistan), they developed sedentary lifestyles based on agriculture, crafts, or local subaltern roles. This way of life did not signify cultural erasure but reflected a constant interplay between adaptation and African identity preservation.

In Sasan Gir (Gujarat) or Sirvan (a Siddi-only village), Indianization is evident in language, cuisine, and clothing. Yet some markers endure—particularly in musical traditions like Goma or Dhamaal, direct descendants of Bantu ritual dances, where drums serve as spiritual conduits and community symbols. The word itself stems from ngoma in Kiswahili, referring both to the drum and the ritual dance invoking ancestors.

In Karnataka, home to about a third of India’s Siddis, African heritage intertwines with local religions: Hinduism (41.8%), Islam (30.6%), and Christianity (27.4%) coexist within the same community. This religious diversity signals not identity dilution, but a flexible territorial anchoring fed by centuries of interaction. Some families even claim spiritual or genetic ties to Barack Obama—a symbolic assertion of global belonging.

In Pakistan, Sheedis in Sindh have built strong internal networks, organized around makans (houses or shrines), with their own patron saints and festivals like the Sheedi Mela of Manghopir. There, African music and the veneration of sacred crocodiles merge in a singular ritual. Again, rurality does not prevent cultural organization or transmission.

Thus, the Siddis’ sedentarization has not meant disappearance. On the contrary, it enabled a form of controlled acculturation, where African identity evolves without dissolving. By integrating into South Asia’s mosaic, the Siddis preserved what mattered most: a living, often vibrant memory of their origin and uniqueness.

III. CULTURE, MEMORY, AND PLURAL IDENTITIES

3.1 Cultural creolization

Siddi culture lies at the crossroads of ancestral and local traditions—between Bantu Africa and South Asia. It reflects a slow process of creolization, where African cultural elements were not merely absorbed but blended, reinterpreted, and at times sanctified in Indian or Pakistani contexts. The result: a distinct, malleable, and resilient Siddi culture.

Language and religion were the first points of adaptation. Siddis speak Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, or Sindhi, depending on location—few retain African lexical elements. Yet some communal expressions, especially in rituals, echo Kiswahili or Amharic syntax. Religiously, a fascinating balance between integration and distinctiveness emerges: predominantly Muslim in Gujarat and Sindh, Siddis are Hindu in northern Karnataka and sometimes Christian—likely due to conversions under Portuguese rule. This pluralism hasn’t fragmented their community, but rather strengthened it through ritualized difference.

Music is where the African legacy resonates most powerfully. Goma, also known as Dhamaal, is more than a dance—it’s a drum-led trance rooted in ngoma traditions, where bodies become vessels for ancestral spirits. In some ceremonies, participants say they are “possessed” by Siddi ancestors.

In Pakistan, the Sheedis’ musical style—marked by syncopated percussion, circular rhythms, and vocal cadences—even permeates popular culture, as seen in the protest song “Bija Teer” or the hits of singer Younis Jani. These survivals are not relics—they are alive, shared, and sometimes fused with modern genres like reggaeton, Sufi music, or urban hip-hop.

Ultimately, Siddi creolization is not just passive blending—it’s a strategic identity, a conscious adaptation, and even a political stance. Affirming African heritage in Indian or Pakistani contexts without retreating inward: this has been their accomplishment for over five centuries.

3.2 Memory Networks and Contemporary Assertion

In societies where marginal histories are often silenced, Siddis and Sheedis stand out for maintaining and reshaping African memory—not as folklore, but as a vehicle for recognition. This memory, woven through ritual practices, family stories, and local institutions, underpins contemporary identity affirmation.

One key expression of this living memory lies in communal rites. In Pakistan, the Sheedi Mela of Manghopir, on Karachi’s outskirts, annually draws fervent crowds to the shrine of Pir Mangho, a revered Sufi saint said to have African origins. The sacred crocodiles in his pond, viewed as spiritual intermediaries, embody a fusion of Islamic belief, animist ritual, and slave memory. The festival is religious, festive, and political—asserting Sheedi presence in Pakistani society while celebrating Africanity.

In India, this memory work unfolds in art, politics, and sport. Figures like Shantaram Siddi, a member of Karnataka’s Legislative Council, or Girija Siddi, a classical Hindustani singer, represent a new generation publicly claiming African ancestry while fully participating in Indian culture. Their success echoes a broader communal effort to reposition themselves.

In Pakistan’s Sindh province, the 2018 election of Tanzeela Qambrani—the first Sheedi woman in a provincial parliament—was a turning point. From the Qambrani house (named after Qambar, the freed slave of Caliph Ali), she embodies the reclamation of a history long instrumentalized. By embracing her African roots, she brings new visibility to this often-erased part of Muslim Asian heritage.

These contemporary affirmations also rely on growing academic reappraisal. Scholarly works, ethnographic documentaries, and diasporic storytelling on social media fuel a counter-memory that resists erasure. The goal is not victimhood, but recognition of a rich past, of roles played in local dynamics, and of dignity preserved through marginalization.

Far from static, Siddi identity is now being redrawn at the intersection of the local and the global—in a dialogue between ancestral drums and modern aspirations.

The history of the Siddis—long marginalized in Indian and Pakistani national narratives—deserves a central place in any discussion of migration, cultural exchange, and sovereignty in Asia. Their path is not that of a forgotten people, but a dispersed and rooted one, continually challenging dominant representations.

They were slaves and generals, state-builders and honor guards, rural farmers and urban poets. Their presence in places as diverse as Murud-Janjira, Hyderabad, Karachi, and the Gir forests shows that East Africa did not merely cross the Indian Ocean—it left a lasting imprint, often silent but never erased.

Ultimately, the Siddis embody a different reading of Afro-Asian history: one of deliberately creolized, strategically integrated, and fiercely dignified diaspora. At a time when India and Pakistan seek to redefine their internal pluralism, acknowledging them is not an act of charitable remembrance—it is a historical necessity.

Sources

- Harris, J.E. (1971). The African Presence in Asia: Consequences of the East African Slave Trade. Northwestern University Press.

- Obeng, P. (2007). Shaping Belonging, Defining the Nation: Cultural Politics of African Indians in South Asia. University Press of America.

- Ali, S.S. (1996). The African Dispersal in the Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. Orient Blackswan.

- Yimene, A.M. (2004). An African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change. Cuvillier Verlag.

- Roychowdhury, A. (2016). “African rulers of India: That part of our history we choose to forget.” The Indian Express.

- Abbas, Z. (2002). “Pakistan’s Sidi keep heritage alive.” BBC News.

- Stuart, A. (2018). “Inside a Lost African Tribe Still Living in India.” National Geographic.

- The New Indian Express (2018). “The Siddis: Discovering India’s little-known African-origin community.”

- Shah, A. et al. (2011). “Indian Siddis: African Descendants with Indian Admixture.” American Journal of Human Genetics, 89(1), pp. 154–161.

Table of contents

I. GENEALOGY AND GEOSTRATEGY OF A MARITIME DIASPORA

1.1 African Origins and Indian Ocean Circulation

1.2 Multiplicity of Statuses: Slaves, Soldiers, Traders, Elites

II. REGIONAL SETTLEMENTS AND SOCIOPOLITICAL STRUCTURES

2.1 African States in Asia: Sovereignty and Military Strongholds

2.2 Rural and Sedentary Siddis

III. CULTURE, MEMORY, AND PLURAL IDENTITIES

3.1 Cultural Creolization

3.2 Memory Networks and Contemporary Assertion