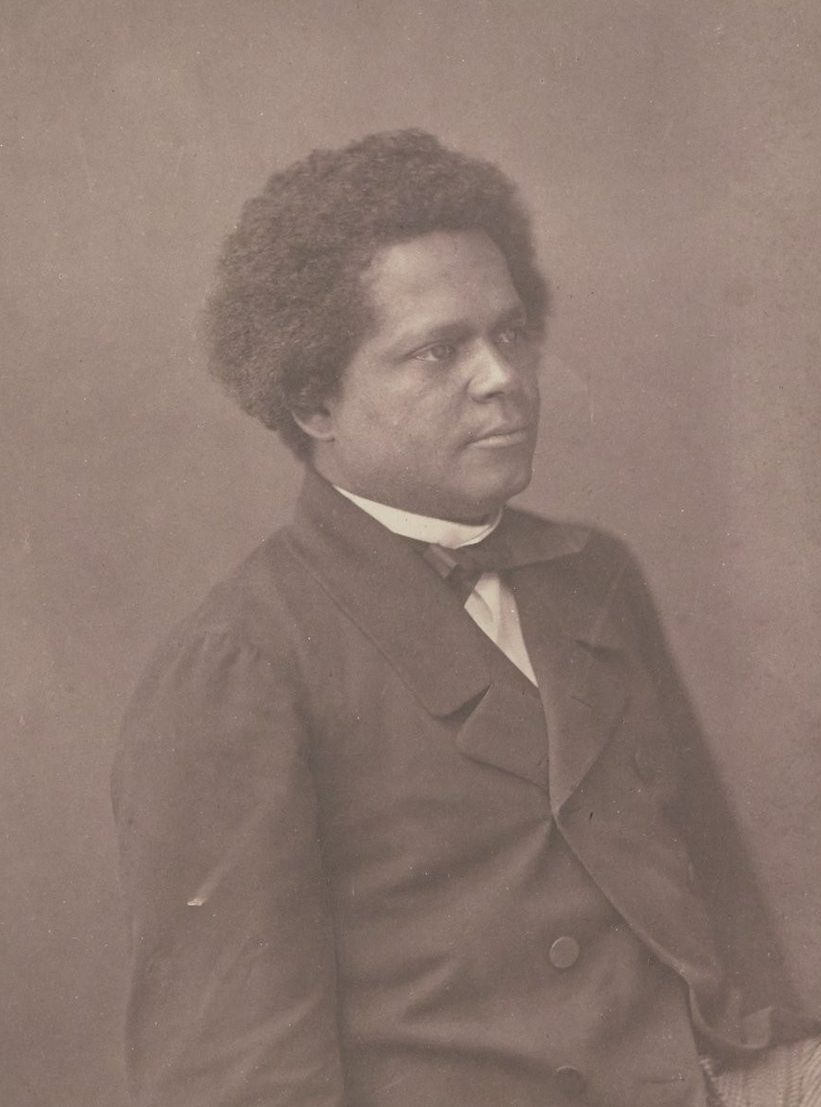

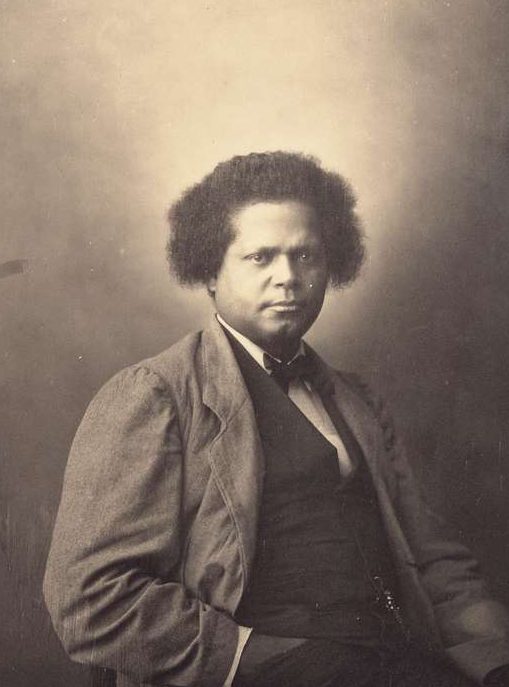

Discover the remarkable trajectory of Victor Cochinat (1819–1886), a Martiniquais lawyer, journalist, and committed intellectual, a forgotten figure of critical colonial thought under the Second Empire. From Fort-de-France to Paris, from law to satire, his path sheds light on the tensions between assimilation and identity affirmation.

A rise within colonial society

Born in 1819 in one of Martinique’s most active cities, Victor Cochinat belonged to the educated Creole elite, molded by French institutions. From a young age, he received a rigorous education based on civil law and rhetoric. He became a lawyer, then a magistrate—first as deputy prosecutor, then as public prosecutor in Fort-de-France. He embodied a generation of colonial-born individuals fully versed in the codes of French administration, yet still confined to a grey area between formal recognition and racial suspicion.

Cochinat held these positions in the years just before and after the final abolition of slavery in 1848. It was a highly sensitive period: Martiniquais society was undergoing profound transformations, with shifting economic and social power dynamics, and legal professionals played a crucial role in upholding the nascent republican order.

Intellectual exile in Paris

In 1850, like many other intellectuals from the colonies, Cochinat chose to “move up” to Paris. There he encountered a world that both fascinated and repelled him. He quickly became the secretary of Alexandre Dumas, a mentor-like figure for Black men of letters at the time. This encounter was more than a collaboration—it symbolized the emergence of an informal diasporic network in the literary circles of Second Empire Paris.

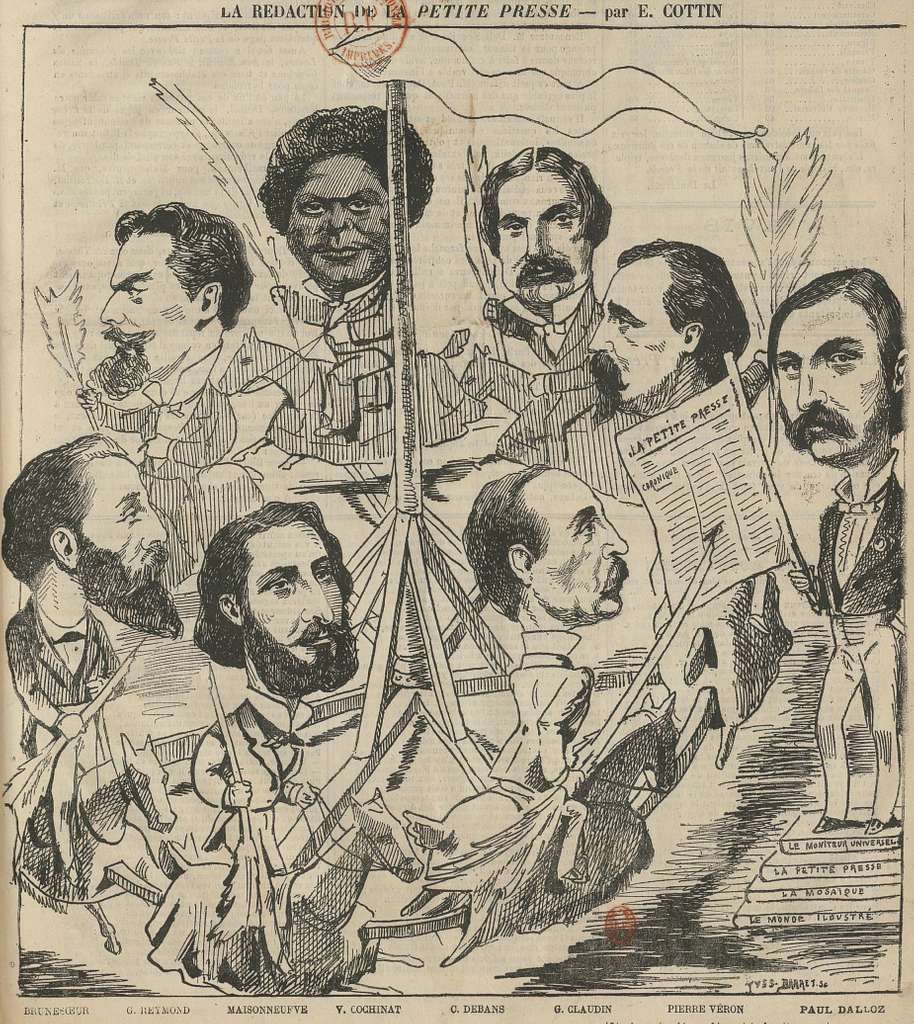

In the years that followed, Cochinat took up the pen. Writing under pseudonyms like Maxime Leclerc or Louis de Roselay, he contributed to numerous publications. In 1856, he became editor-in-chief of Le Figaro-programme, then directed Le Foyer, a cultural journal with republican leanings. There, he developed a critical, often mocking and biting style. He actively participated in the cultural battles of his time, notably against the Parnassian movement, and denounced literary conformism masquerading as objectivity.

His famous attack against the “Vilains Bonshommes,” the mocking nickname he gave to the Parnassians who praised Coppée’s Un Passant in 1869, illustrates his intellectual independence and refusal to be confined to rigid ideological camps.

Advocating for a colonial voice

In the latter part of his life, Cochinat sought to reconnect with his roots. He traveled to Haiti—a symbol for him of a free Black state, despite its instabilities—and in 1880, he founded La Revue exotique. The aim was clear: to provide a space for intellectual productions from the “peripheries.” In his mind, it was about demonstrating that colonized peoples were capable of autonomous thought, critical insight, and creative expression.

Launched under the patronage of the Académie des Palmiers, whose members included Hugo, Schoelcher, and Leconte de Lisle, the journal lasted only one year. Nevertheless, it was a foundational experience. After his death in 1886, the venture was revived in 1889 as Alliance universelle. Though it found institutional success, it lacked the pioneering, critical spirit instilled by Cochinat.

A forgotten figure of colonial universalism

Victor Cochinat died in Fort-de-France on October 6, 1886, far from the Parisian salons. His works are scattered, rarely reprinted, and his role underestimated. Yet he represents a crucial turning point: the moment when colonial subjects began to claim public speech, to produce situated discourse, and to reject being merely objects of reform or assimilation.

Cochinat’s journey reveals the constant tension between integration and critique, loyalty and subversion. A lawyer turned polemicist, an assimilated Creole who became an advocate for an “exotic” world to be heard in the intellectual arena—he stands as one of the first figures of a Francophone diasporic thought.

References

- Janvier, Louis-Joseph. La République d’Haïti et ses visiteurs (1840–1882), Paris, Marpon et Flammarion, 1883, 636 p.

- Chemla, Yves. “Comment la littérature haïtienne nous apprend à penser autrement,” Littafcar (academic site on African and Caribbean literature), March 3, 2014.

- Le Voleur illustré, 61st series, vol. 40, no. 1635, November 1, 1888, p. 450.

- Cochinat, Victor. Lacenaire, ses crimes, son procès et sa mort, Paris, Jules Laisné, 1864.

Summary

- A rise within colonial society

- Intellectual exile in Paris

- Advocating for a colonial voice

- A forgotten figure of colonial universalism