Before they were characters of folklore, Bouki and Ti Malice were prisms. Through them passed centuries of slavery, resistance, and humor as a means of survival. From the West African savannah to the Haitian hills, their adventures continue to reflect the tensions of power, trickery, and naivety. Portrait of a mythical duo, as cruel as they are tender.

When the bush reaches the Caribbean

Before they became figures of folklore, Bouki and Ti Malice were prisms. Through them passed centuries of slavery, resistance, and humor as an art of survival. From the West African savannah to the Haitian hills, their adventures continuously reflect tensions between power, cunning, and naivety. Portrait of a mythical duo, as cruel as they are tender.

Originally, before they became flesh-and-blood characters in Creole imaginations, Bouki and Ti Malice crawled and leaped on all fours in the savannahs of West Africa. There, in stories passed from village to village by griots, Bouki was a hyena (“Bouki” in Wolof), with a clumsy gait, a voracious jaw, and the scent of submission clinging to its fur. A beast of disgrace and hunger, it symbolized failure, heaviness, the creature that obeys more than it understands.

Opposite him stood Leuk the hare. Small, nervous, elusive. A show-off of the underbrush who never won by strength but always by wit. Excessively clever, sometimes cruel in jest, but always quick. In these original tales, the confrontation is constant: the hyena chases, the hare dodges. Bouki growls, Leuk counters with trickery. It’s the eternal duel between brute muscle and rebellious intellect.

This duo wasn’t just pastoral entertainment. It was pedagogy, social satire, and a staging of power dynamics in African societies. Leuk the clever never laughed for free: he laughed to survive, to outsmart hunger, the king, and the established order. And Bouki, in his defeats, sometimes embodied the people’s flaws (naivety, laziness, weakness) but also their resilience, their ability to rise again despite humiliation.

When these stories crossed the Atlantic in the holds of slave ships, the African animals did not remain the same. They transformed. Under the Caribbean sun, Bouki and Ti Malice gradually shed their fur to take on human traits. Their voices thickened, their faces took on the wrinkles of the neighborhood elders, and their schemes and foolishness became familiar anecdotes. The original bestiary became a gallery of characters, sketched from life.

In the Haitian countryside, Bouki became a famished peasant, often dressed in rags, always hungry, sometimes endearing. Malice turned into a thin young man, quick-witted, willingly a trickster, irresistibly charming. The animal traits didn’t disappear—they were diluted into gestures, glances. They simply changed skin.

In Martinique and Guadeloupe, the transformation was more nuanced. One still finds Zamba, the slow and gullible feline, the local embodiment of Bouki. The hare became Lapin or remained a sly allegory. The duel endures, but each island infuses it with its own flavor: the story adapts to the land, the Creole, the laughter of children under the huts.

Interestingly, this animal-human dynamic isn’t unique to the Afro-Caribbean world. It quietly converses with European fables. The naïve Big Bad Wolf isn’t so far from Bouki, and the clever Reynard the Fox could well be a distant cousin of Ti Malice. But where the French fox acts with aristocratic coldness, Malice acts with urgency. He doesn’t deceive to dominate—he deceives to survive. A crucial nuance, born of a different history, steeped in pain and resourcefulness.

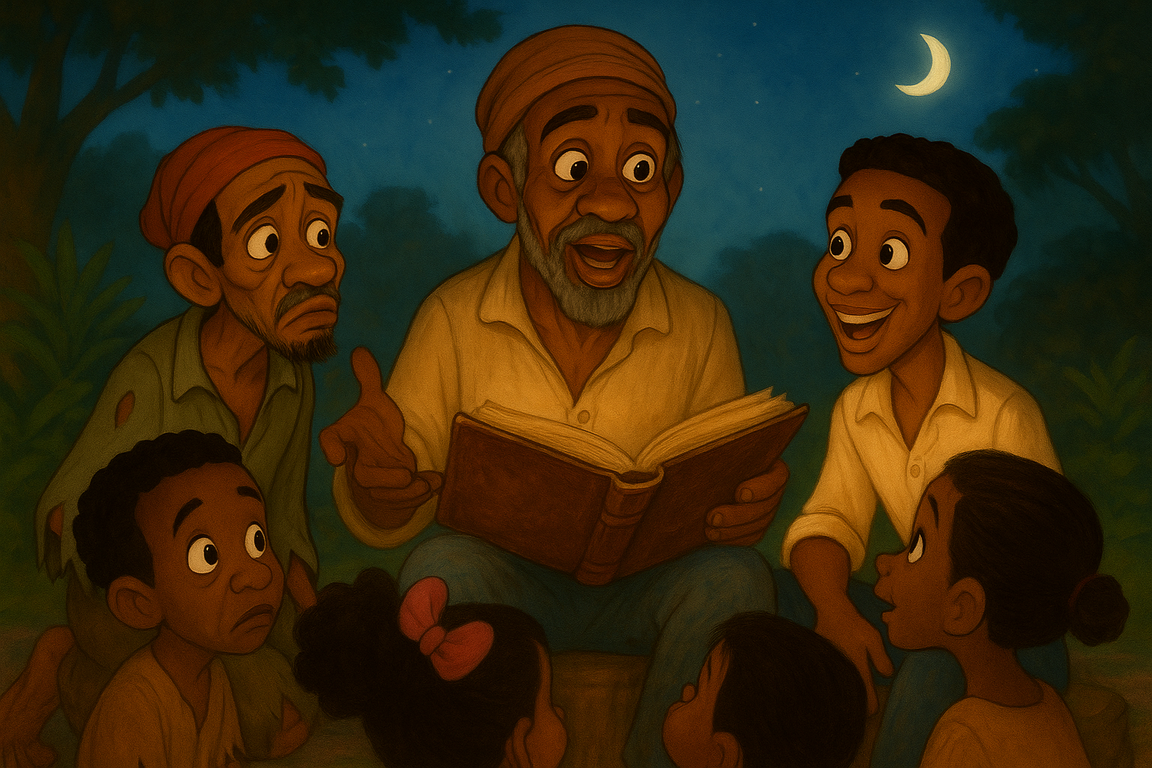

In the plantations, chains left little room for dreams. But at night, when the work ended and sweat dried slowly on scarred backs, another voice emerged. Not scholarly or official—a soft, mischievous voice full of shadows and winks. It asked: “Krik?” and another answered: “Krak!” Then the tale would begin.

These stories, featuring Bouki and Ti Malice, were never innocent. Beneath their humor lay a distorted mirror of the colonial world: the master became the fool, the underdog got his revenge, and survival came through cunning deceit. Ti Malice wasn’t just a prankster—he was the voice of the captive turning the established order on its head with mischief. Bouki reminded listeners of the tragic effects of gullibility—but also the dignity of existing despite it all.

These tales had to be told after dusk. Not just an aesthetic rule—it was a sacred code, inherited from Vodou and African traditions. Telling stories before nightfall risked summoning spirits before their time, inviting misfortune or the evil eye. In this context, storytelling was not merely a popular art—it became ritual, pact, and release.

To laugh in the darkness of slavery was not to escape reality—it was to surround it differently. With a punchline, a twist of absurdity, Africanized storytellers created a barrier against daily terror. The whip could do nothing against the well-placed word. And so Bouki and Ti Malice, born in the savannah, became nighttime heroes of resistance in the cane fields.

Mirror of a post-traumatic black world

Bouki, in the mouths of the elders, is the magnificent fool. The one you mock but never reject. The one who falls for every trap, especially the obvious ones, and yet returns in each story—head bowed, but heart intact. He doesn’t really learn—or learns poorly. He trusts too easily, too often. But he embodies a raw form of humanity—vulnerable, moving in his persistence.

In Haiti’s oral storytelling theatre, Bouki is not just Ti Malice’s victim—he also reflects the people’s weaknesses: hunger that clouds judgment, fatigue that dulls vigilance, the need for love that blinds. He is lazy sometimes, gluttonous often, always a bit dim. But he loves his children, cherishes his wife (when she exists), and above all: he endures. Bouki never gives up.

There’s something of the Creole Sisyphus in him. With each fall, he rolls his boulder again. When Malice humiliates him, he walks on—barefoot, ego bruised, but spirit unbroken. He’s not a triumphant hero. He’s a stubborn survivor. A figure of quiet dignity.

In a world where cunning is king, Bouki—through his lack of deceit—becomes paradoxically the most human. He holds up a cruel but honest mirror: one that reflects our naïveté, our too-simple dreams, and our capacity to remain standing, even in ridicule.

Ti Malice is the quick-witted brain of the duo. A character who doesn’t settle for survival—he wants to dominate, manipulate, bend reality to his will. Where Bouki endures, Malice anticipates. Where one believes, the other suspects. He is the bastard child of cunning and vice; one who quickly understands that in a world built on injustice, ethics are a luxury for the naïve.

Often described as playful and mischievous, beneath the comedy Ti Malice hides an almost unsettling clarity. He sees Bouki’s flaws as opportunities. He cheats, steals, lies—always with a smile. And it’s that smile that unsettles: it’s the mask of an intelligence that, in another context, might have made him a brilliant strategist or politician.

Ti Malice is also the symbolic revenge of the oppressed who refuses to bow. He represents a form of resistance—amoral, but pragmatic. In stories rooted in slavery, he becomes the voice of those without power who use cleverness as a weapon. He doesn’t seek to overturn the system—he exploits it, bypasses it, slithers through it.

But that strategy has a cost: Malice is alone. His victories are often bitter. For while people laugh at his tricks, they distrust his duplicity. He charms, then betrays. He entertains, but doesn’t inspire trust. He is admired from a distance, like a flash fire: with fascination—and caution.

He is the other face of the post-traumatic Black world: the one that, instead of enduring, chooses to strike—even at the risk of becoming a monster in the mirror.

Behind their cascading laughter and papier-mâché grimaces, Bouki and Ti Malice perform a far graver comedy than it seems. Each tale, each trick, each humiliation masks a sharp (sometimes cruel) portrayal of social dynamics inherited from slavery and perpetuated in post-colonial society. These two, seemingly accomplices, subtly embody a fracture: that between dominated and dominator, the one who suffers and the one who maneuvers.

Bouki, through his passivity, his lack of discernment, and his role as perpetual loser, reflects the image of those left behind by the structures of power. He is the naïve peasant, the exploited worker, the ordinary man promised the moon who always ends up footing the bill. Opposite him, Ti Malice—through his tricks, his words, his social flexibility—embodies opportunism, but also, paradoxically, a certain Black or mixed-race elite, educated in the shadow of the colonial system and often willing to bend to climb.

They might be seen as uncle and nephew, but also as people and bourgeoisie, suffering body and calculating mind. The dynamic between them is deceptively playful. At its core, it questions betrayal: what is the worth of cunning if it is built on the backs of one’s own? And what is the worth of virtue if it leads only to repeated failure?

In this popular theatre, Bouki and Ti Malice become archetypes of a class struggle that goes far beyond Haiti. They raise a brutal question: in a world shattered by colonization, who has the right to be clever? And more importantly—at what cost?

When fiction illuminates history

For a long time, Bouki and Ti Malice existed only in the air—in the shared laughter under verandas, in warm night gatherings where speech offered shelter. They belonged to pure orality, leaving no written trace but imprinting themselves in bodies, intonations, and complicit silences. Telling the tales of Bouki and Malice was an art. Writing them down risked freezing them.

But eventually, these figures had to migrate to paper, if only to avoid disappearing. It was Alibée Féry, 19th-century Haitian writer and storyteller, who dared first. With him, the characters gained fixity—perhaps at the cost of some fluidity. The word took root; the dialogue settled on the page. A new era began: that of Haitian popular literature.

A century later, between May 1991 and May 1992, the dialogues of Bouki and Malice returned in the pages of Le Nouvelliste, a Port-au-Prince daily. Each week, a new episode: readers followed the duo’s escapades like a television series. Tales once whispered became serials, reaching an urban, literate audience eager to see its rural and Black roots resurface in print.

Other voices took up the torch: Suzanne Comhaire-Sylvain in Le Roman de Bouqui, Jean André Victor with his 50 Selected Dialogues, Colette Rouzier with a children’s version. Each author adapted, translated, condensed—but all preserved the essence: that of an elusive folklore that resists erasure, even when confined between two covers.

Far from diluting their power, the transition from oral to written allowed Bouki and Ti Malice to enter Haiti’s literary pantheon—while keeping the mischievous, popular spirit that defines them.

Tales are not mere entertainment. In post-slavery Black societies, they are places of memory. A living, embodied memory—not passed down through official archives (too often silent or biased), but through the voices of elders, trembling intonations, silences heavy with what can no longer be said. Bouki and Ti Malice, in this light, are more than characters: they are conduits. Vessels of a people’s emotional memory.

Through them, the full range of the Black experience emerges: hunger, betrayal, ingenuity, humiliation, and also love. Each story becomes a living metaphor. A grotesque little scene (Bouki losing his ox, tricked by Malice, returning with bloody feet) becomes a shard of history. The history of a people repeatedly deceived—yet somehow still moving forward.

Here, the tale functions as an emotional capsule. It transmits knowledge (moral, practical, political), but above all, it transmits a sensation: that of having lived—despite everything. That’s why these stories are told to children. Not to put them to sleep, but to awaken them to the world. The laughter they provoke is often nervous, biting. It’s laughter that heals as much as it stings. A laughter that says:

“Yes, we suffered. But look what we made of that pain.”

And then there is the language—a Creole built on imagery, a French laced with oral music—that carries the tales of Bouki and Malice. This language is an archive in itself. It contains the shocks, wounds, and transformations of a world shaken by colonial violence. When we listen to these stories, we also hear the voices of the absent—those who left no writing but whose imprint traverses the centuries through the magic of storytelling.

A universal legacy, rooted in blackness

One might think Bouki and Ti Malice belong to a bygone world—of earth huts, candlelit evenings, and elders speaking slowly. And yet, their figures still resonate far beyond the Haitian hills or Guadeloupean plantations. Why? Because at their core, they speak to a universal relationship with power, weakness, cunning, and survival. Their language is that of raw humanity—stripped of pretense, face-to-face with its most primal instincts.

We find their counterparts everywhere: in Anansi the Spider of Ghana, in the trickster Br’er Rabbit of the American South, in Ti Jean of Creole Louisiana. Even in cinema and pop culture, the opposition between trickster and dupe remains a fundamental narrative device. These two figures—though deeply rooted in an Afro-Caribbean soil—are not confined by geography. They speak to a broader truth: that of societies built on imbalances of power.

Ti Malice embodies cunning as a form of popular genius; Bouki, gullibility as a universal trait. In a world where systems of domination constantly renew themselves—economic, cultural, digital—their lessons remain painfully relevant. There will always be Malices who bend the rules—and Boukis who fall into the trap.

But this universality is never abstract. It is embodied. It is Black. It is Creole. It comes from a lived experience where injustice is not an idea, but a daily fact. That’s the power of Bouki and Ti Malice tales: they show the world as it is, while letting us believe it could be otherwise.

A wisdom disguised in laughter

Beware of tales. What they say lightly is often what history books avoid saying heavily. Bouki and Ti Malice are not just entertainers from Haitian folklore. They are the voice of collective memory—the guardians of a popular philosophy born in the shadows of the slave trade, ripened in the cane fields, passed down through the trembling voices of grandmothers at twilight.

Through their eternal duel (naïve vs. cunning, heart vs. mind, muscle vs. speech), they map the social, racial, and moral tensions of the Afro-diasporic world. A world where irony is a survival strategy, where laughter is never just a game.

And perhaps these characters understood our era better than many analysts. In a world saturated with manipulation, political lies, exploited naivety, and unequal relationships, Bouki and Ti Malice continue to ask the right question:

Is it better to be a fool with dignity… or clever without scruples?

Perhaps that’s where their true wisdom lies—in that tension. A wisdom masked by laughter, but forged in the raw experience of the world.

About — passing it on without betraying: Griokids, inheriting memory

If Bouki and Ti Malice have traveled through the centuries, it is no accident. It is because voices continued to carry them. Today, this mission takes a new form with Griokids.com, a platform dedicated to transmitting African and Caribbean folkloric heritage to the young—without ever talking down to them.

Going against the grain of cultural globalization that flattens everything in its path, Griokids bets on joyful rootedness. There you’ll find animated tales, audio stories, educational resources—and most importantly, a fierce desire to preserve the warmth of orality, the breath of stories told with love—in Creole, in Wolof, in Lingala, in French… with accents from everywhere and from yesterday.

Griokids does not educate—it roots. It does not fossilize—it brings to life. Because passing on is not freezing—it is continuing the dance. And in this dance, Bouki and Ti Malice are still dancing—mischievously.

Discover their adventures at www.griokids.com

Sources

Table of Contents:

- When the bush reaches the Caribbean

- Mirror of a post-traumatic Black world

- When fiction illuminates history