In May 1803, on the shores of Georgia, a group of Africans reduced to slavery chose to walk into the water rather than live on their knees. This act, long buried by official history, was passed down in whispers within Black communities, eventually becoming a foundational myth of Afro-diasporic resistance. Igbo Landing is the place where the sea became sanctuary, where the rejection of inhumanity was etched into the silence of the marshes. This is no legend—it is a legacy.

The silence of the waters, the cry of the ancestors

“The water spirit brought us here, the water spirit will take us home.” So sang, according to oral tradition, the chained Igbo as they slowly walked into the marshes of Dunbar Creek, Georgia. No tears, no screams, just a chant in their mother tongue, a final collective prayer addressed to the divine to reject the unspeakable.

It is May 1803. The transatlantic slave trade is at its height. A group of seventy-five African captives, newly arrived in Savannah, is resold to work on plantations on St. Simons Island. But once aboard the schooner meant to take them there, these men and women—mainly from the Igbo region (present-day southeastern Nigeria)—overpower their captors, seize the ship, and in a final act of sovereignty, willingly walk into death rather than embrace servitude.

Long dismissed as a folk legend, this true event—now known as Igbo Landing—embodies the ultimate form of revolt: a body liberating itself through water when the land promises nothing but chains. More than an overlooked historical episode, Igbo Landing has become a structuring myth rooted in the memory of African and Afro-descendant peoples—a song of dignity passed on orally, generation to generation.

This story, poised between reality and the sacred, deserves to be revisited as a cornerstone of diasporic resistance—a repressed memory now exhumed, not without shivers.

A radical act of resistance (the historical fact)

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the transatlantic slave trade was at its peak. The coasts of West Africa—between present-day Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon—became zones of massive deportation. Kingdoms such as Biafra, the Igbo states, and Dahomey, destabilized by internal conflicts or European incursions, fueled the human trade, often serving European commercial interests.

In this context, the Igbo—farmers, traders, and thinkers known for their strong sense of community and freedom—were both targeted and feared. Slave traders considered them rebellious, hard to break, sometimes incompatible with plantation discipline. This reputation was well earned: the Igbo maintained a deeply rooted tradition of decentralized governance and resistance to arbitrary authority. Their spirituality, centered around the god Chukwu and nature spirits, gave them a strong identity that transcended the humiliation of displacement.

So, when these men and women were captured and torn from their homeland, they did not arrive on American shores stripped of identity or will. They carried a spirit of defiance. And it was this spirit that destiny would ignite in the waters of Georgia.

Their voyage to Savannah began like so many others—in the fetid hold of a slave ship, amid vomit, chains, and gasps of agony. It was the grim routine of what we now call the Middle Passage, a two-month transoceanic journey from West Africa to the American colonies, with mortality rates sometimes exceeding 20%.

But this voyage carried an anomaly: the presence of a group of Igbo, known for their cohesion, resistance to enslavement, and sacred worldview. Upon arrival in Savannah, they were sold to two prominent plantation owners—John Couper and Thomas Spalding—for $100 per person. The destination: St. Simons Island, off the Georgia coast, where cotton and rice fields demanded compliant labor. But these were not compliant people.

For this short coastal journey, the Igbo were placed aboard a smaller schooner, known as either The Schooner York or The Morovia. But as the vessel made its way up Dunbar Creek, the tension reached a climax. This was no longer a simple transport of human cargo. Something was fermenting in the hold—a strategy, a tacit pact, perhaps even a prayer.

And then the unimaginable happened: the captives broke their chains, rebelled, disarmed or drowned some crew members. The schooner ran aground. This was no impulsive mutiny—it was a reconquest. Not of physical freedom (they knew the land held no safety) but of their own fate.

Thus began a distinct chapter in the history of slavery: one where the enslaved took to the sea not to flee, but to deliberately vanish—like disgraced samurai.

The ship ran aground in the calm but treacherous waters of Dunbar Creek. The silence that followed was almost ceremonial. On board, drowned white bodies floated or sank. The Igbo did not flee. They did not try to hide in the marsh or pose as free people. They walked, with purpose, to the shore.

It is here that the tale enters the sacred realm. According to various oral testimonies collected over the centuries—notably by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s—the captives, led by a spiritual leader or elder, chanted in their native tongue:

“The water spirit brought us, the water spirit will take us home.”

It was neither a plea nor an escape. It was an incantation.

One by one, in line, they entered the water. Their chains broken, they did not seek freedom on the oppressor’s terms. They reclaimed it on the terms of their faith, their ancestors, their dignity. They chose the liquid element as a threshold—between this world and the next, between bondage and remembrance.

This scene, fragmentarily reported by Roswell King, a local plantation overseer, was brief and irreversible: the Igbo refused to live on land that deemed them livestock. They dissolved into the swamp with the fervor of a people who, even in death, rejected degradation.

This was no individual suicide. It was a collective, ritualized act, perhaps inspired by African funerary traditions—or by the certainty that dying together in water was better than surviving alone in the fields with bent backs.

The message is clear, even two centuries later: better to vanish upright in the water than live on your knees in the mud.

Between history and mythology

In the 1930s, long before universities rediscovered the historical depth of Igbo Landing, it was elders without titles who kept its essence alive. Among them, Floyd White, Wallace Quarterman, and other African Americans over eighty, interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project. These elders—often direct descendants of the Gullah—did not cite dates or official records, but spoke with the conviction of those who know what history forgot.

“They went into the river singing, to go home. They didn’t want this life here,” White recounted nearly a century after the events. Such testimonies were not isolated. They wove an invisible web of memory, passed down without paper or ink, but with deep conviction.

Among the Gullah (an island-based African American community directly descended from West African cultures), this story becomes more than a memory—it becomes a parable. Over time, the Igbo walk into the swamp transforms. It’s no longer just about captives fleeing servitude. It becomes a tale of Africans literally walking on water—as if defying the physical laws of the New World to return to the old one.

In this mythic version, the waters of Dunbar Creek are not a grave but a bridge. A mystical passage between continents. A reversal of the rules of humiliation. The American soil, sullied by slavery, is rejected. The Atlantic becomes womb again.

And this oral memory, transmitted across generations, becomes a form of resistance. Because while white archives forget, Black speech engraves.

As the Igbo Landing narrative seeps into the consciousness of African American communities in the U.S. South, it undergoes a mythological transformation. The image of captives walking into the water evolves, in some versions, into Africans literally flying away—escaping bondage by defying gravity. The story shifts from a refusal of servitude to a celestial return.

In several testimonies collected by the Federal Writers’ Project, the story takes on a supernatural dimension: after defying the overseer’s whip, the enslaved plant their tools into the ground (a gesture of rupture), then rise into the air.

“They flew like birds, they left, went back home, to Africa.”

Some speak of them transforming into vultures, others into angels. The raw fact becomes fable; the revolt becomes flight.

This shift is not a negation of historical truth, but a symbolic enrichment. In African diasporic traditions, flight has always meant more than movement. It is a spiritual liberation. To fly is to escape the suffering body, the master, the chains, the fields. To fly is to go home when exile land accepts you no other way.

Anthropologist Terri L. Snyder sees in this a poetic extension of the collective suicide at Igbo Landing. Others, like Jeroen Dewulf, argue the myth predates it—rooted in tales from the Loango and Kongo regions of Central Africa. Whatever its exact origin, the myth of the “flying Africans” speaks to a common need: to imagine an escape when freedom becomes unthinkable.

It is also a myth that addresses those who remain. These are not stories for passive spectators. They always transmit something—an incitement not to resign. The flight of the ancestors becomes the momentum of the descendants.

The myth of Igbo Landing—and the flying Africans it spawned—has never stopped taking flight from one generation to the next. It permeates literature, cinema, music, and contemporary art. It is not static folklore confined to the margins; it is a living motif, endlessly reinterpreted, an invisible thread through Black cultural history.

In Song of Solomon (1977), Toni Morrison makes flight a central metaphor for emancipation. The main character, searching for his roots, discovers a family legend in which men took flight to escape slavery. Without explicitly naming Igbo Landing, Morrison captures its spirit: the idea that flight is a poetic response to oppression—a refusal to be anchored in pain.

In Roots, Alex Haley directly references the Igbo’s collective suicide as a sacred act. He frames it not as a tragedy, but as an act of memory and transmission. Similarly, Paule Marshall, in Praisesong for the Widow, builds an entire novel around the pilgrimage of an African-American woman retracing her ancestral roots to St. Simons Island, where she physically feels the weight of sacrifice.

Cinema has followed suit. Julie Dash’s masterpiece Daughters of the Dust (1991) draws heavily on the myth of the flying Africans. Ethereal landscapes, whispered dialogue, and silences filled with spirit—all evoke Igbo Landing.

Later, Beyoncé visually references the story in her “Love Drought” video from Lemonade, where Black women walk into water in what appears to be an ancestral ritual. Again, there’s no direct citation—but a clear aesthetic and spiritual allegiance.

Finally, pop culture cements the legacy of the myth in Black Panther (2018). In the final scene, the dying character Killmonger chooses to be buried at sea:

“Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from the ships, because they knew that death was better than bondage.”

This line—simple and sharp—resurrects in an instant the entire submerged memory of Igbo Landing.

Popular culture, often dismissed as mere entertainment, becomes here a tool of historical rehabilitation. It makes visible voices long drowned. It lifts the story where the archive fell silent.

Silence and memory

Some silences weigh heavier than chains. For over two centuries, the waters of Dunbar Creek held not only bodies but a story that official America refused to tell. No monument, no plaque, no public recognition acknowledged that on this shore, men and women chose death over enslavement. The story of Igbo Landing wasn’t denied—it was simply… ignored.

And the disregard went further. In 1940, in the heart of a segregated South, local authorities decided to build a sewage treatment plant precisely on this sacred site. Where African ancestors had died to preserve their dignity, the waste of the living would now be dumped. The symbolism is brutal. History wasn’t merely erased—it was desecrated.

This choice was no accident. It fits a well-practiced American tradition: suppressing rebellious memories, desacralizing sites of Black resistance, burying acts of dignity under administrative concrete.

Yet the memory of Igbo Landing never vanished—it lived on quietly in the Gullah communities, in stories told during vigils, in the inhabited silences of elders. The State could deny it, but the land remembered. And one day, the descendants would remember too.

It would take until the dawn of the 21st century for Dunbar Creek’s banks to be recognized for what they truly are: a sanctuary. And ironically (or perhaps symbolically), that recognition didn’t come from federal institutions or major universities. It came from the youth.

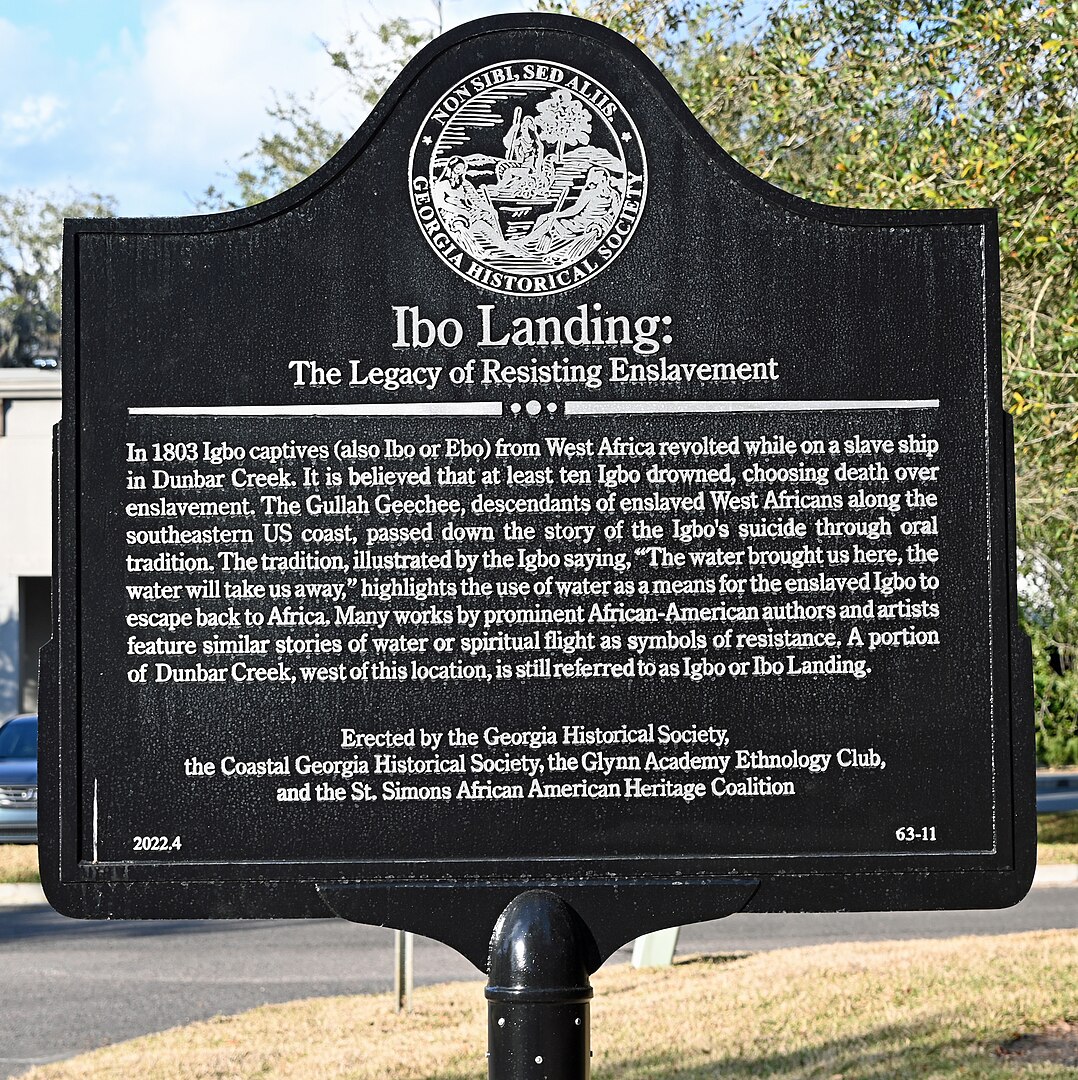

In 2021, a group of students from the Glynn Academy Ethnology Club in St. Simons Island undertook a meticulous historical investigation of Igbo Landing. With the determination only a fresh conscience can bring, these teenagers combed through archives, cross-referenced testimonies, wrote a thorough report, and submitted a formal request to the Georgia Historical Society to erect a historical marker—a real one. In granite, with engraved words, and academic validation. Not just another oral legend, but official state recognition.

Their request was accepted. The emotion was overwhelming. Thanks to them (supported by the Coastal Georgia Historical Society and the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition), a commemorative plaque was finally funded, installed, and inaugurated on May 24, 2022. It now stands in a green space near the site—since the creek itself, bitter irony, is still privately owned.

This gesture doesn’t erase yesterday’s humiliation, but it does offer some repair. It gives the descendants of the Igbo—and the entire Black diaspora—a point of anchoring. A place to lay flowers, prayers, stories. A place to say:

“We have not forgotten you. We will not forget you.”

This marker isn’t a museum piece. It’s a beacon in the sea of amnesia. And it was placed there by a generation that, in refusing erasure, carries on the original act of resistance.

Today, Igbo Landing is no longer just a swamp on a Georgian island. For many, it is sanctified ground. A place where death was freely chosen—not inflicted—and which has taken on a near-mystical power. Every step through the tall grasses of Dunbar Creek, every breath of salty air, is a silent reminder: here, the Atlantic did not merely swallow bodies—it preserved a soul.

Since the 2000s, historians, artists, activists, African priests, and members of the diaspora have made pilgrimages there. Some pour holy water, others sing ancestral songs. In 2002, a major ceremony was organized by the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition. Participants came from all over the U.S., and from Nigeria, Benin, Haiti, or Belize (countries also marked by similar acts of resistance), walking together toward the site to “free the souls” of the Igbo. As if, over two centuries later, the ancestors were still waiting to be acknowledged.

To the Gullah communities, this site has long been seen as a threshold between two worlds. According to local accounts, one might hear chants carried on the wind or glimpse figures in the mist. The creek is not haunted—it is inhabited. By a memory that refuses to fade. By a force that speaks to the living.

It’s no coincidence that Igbo Landing is now studied in local schools, included in history curricula along the Georgia coast. Teaching this story means accepting that U.S. history does not begin with the Founding Fathers—but also with those who, torn from Africa, refused to surrender to their fate, even in death.

Between politics, art, and resistance

In a world saturated with narratives of submission and suffering tied to slavery, the story of Igbo Landing changes everything. It upends the grammar of martyrdom. It does not recount broken bodies but intact wills. It resists being boxed into easy compassion. It disturbs, because it opposes determined silence to the slave order—collective death to domesticated survival.

At Igbo Landing, death is not defeat. It is a decision. A form of ultimate autonomy. These men and women could have fled, scattered, or reluctantly assimilated into the system. But they chose an ending—together—as a united people. This was not suicide in the Western sense—it was ritual, proclamation:

We are not for sale. We will not be owned.

This choice echoes other Black resistance movements across the Americas: the bloody revolts of Saint-Domingue, where slaves brought down an empire; the Maroons of Suriname and Jamaica, who built their own mountain societies; Nat Turner, who led a messianic uprising in Virginia in 1831; Harriet Tubman, who led enslaved people out of hell, famously saying:

“I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.”

All these acts—escape, revolt, sabotage, defiance—share a common DNA with Igbo Landing. But this one carries a deeper gravity: it doesn’t seek survival, it demands respect. Even unto death.

In that sense, Dunbar Creek becomes an open-sky scripture—a foundational counter-narrative: that of Africans who, at the heart of the slave machine, never surrendered their sovereignty.

Where water spoke louder than chains

Dunbar Creek is not merely a Georgian swamp where a few bodies dissolved over two centuries ago. It is a threshold. A lingering whisper at the heart of diasporic consciousness. A wound turned landmark.

The Igbo of 1803 left no diaries, no written records, no graves. But they left something greater: a pure act. Irreducible. A refusal that travels through time. A song carried by water:

“The water spirit brought us here, the water spirit will take us home.”

That song didn’t drown. It was passed on—through vigil, through story, through song and image—until it imprinted itself in global culture, sometimes without people knowing where it came from.

Igbo Landing reminds us of a brutal truth: Black memory never dies of its own accord. It is often buried, denied, ignored. But it only takes a word, a gesture, a work of art—and it rises again. And when it does, it disturbs. Because it speaks of pride, mysticism, voluntary sacrifice. It says that slaves weren’t always submissive. That sometimes, they refused to enter the oppressor’s history. That they chose the sea as their final word.

In a world still haunted by the legacies of slavery, the act of Igbo Landing has lost none of its power. It invites us to reinvent our narratives, to sanctify the desecrated, to listen for songs we thought extinct.

And above all, it compels us to ask a disturbing—perhaps the most essential—question:

if we had to choose between surviving on our knees or disappearing standing tall… what would we have done?

Sources

Berlin, Jacqueline. 2003. “Researcher Has New Version of Legend.” The Brunswick News, August 18.

Buxton, Geordie. 2007. Haunted Plantations: Ghosts of Slavery and Legends of the Cotton Kingdoms. Arcadia Publishing.

Ciucevich, Robert. 2009. Glynn County Historic Resources Survey Report. Brunswick, GA: Glynn County Board of Commissioners.

Summary

- The Silence of the Waters, the Cry of the Ancestors

- A Radical Act of Resistance (The Historical Fact)

- Between History and Mythology

- Silence and Memory

- Between Politics, Art, and Resistance

- Where Water Spoke Louder than Chains

- Sources