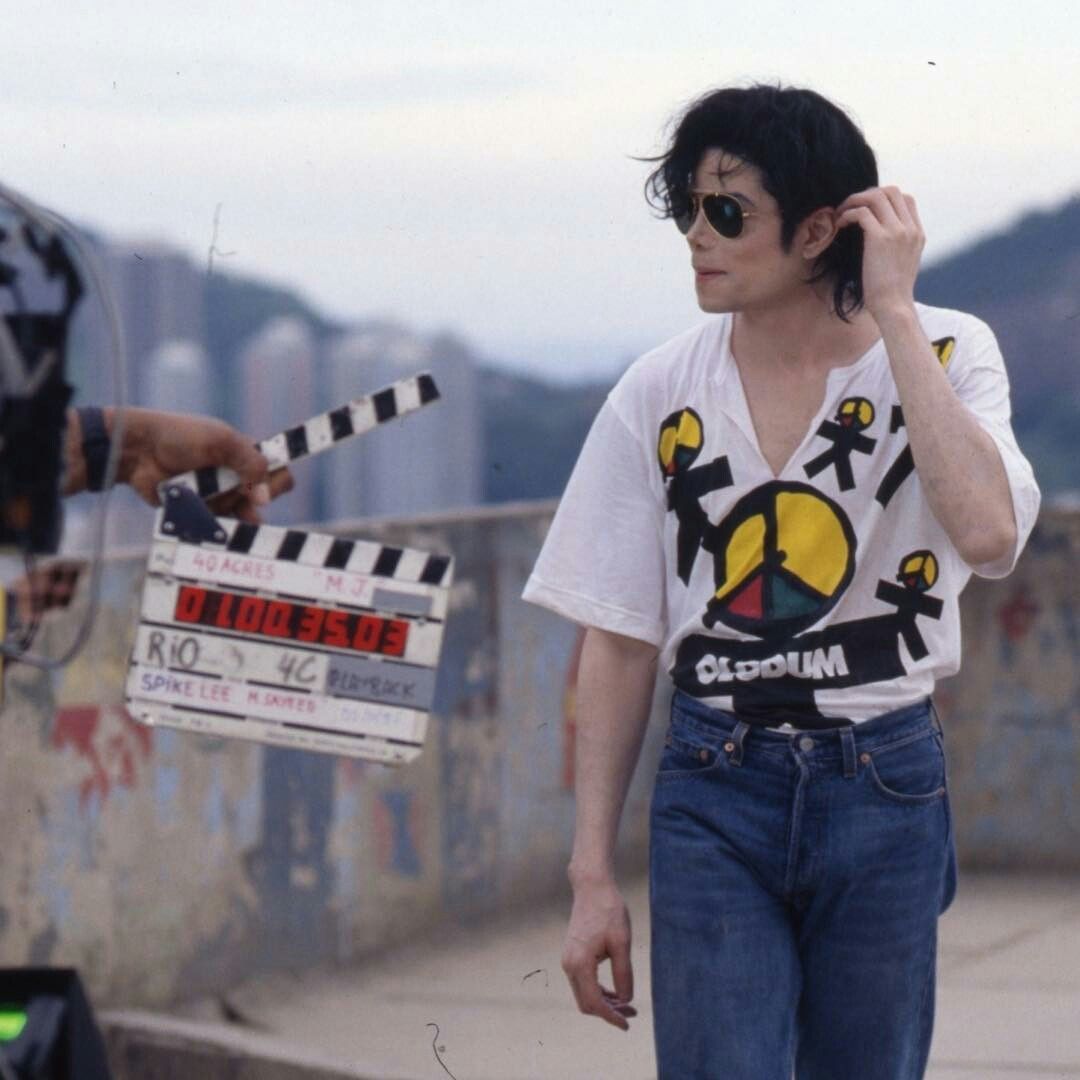

In 1996, Michael Jackson shot a music video in a Rio de Janeiro favela. What the world didn’t know was that this historic shoot was only possible thanks to the approval of… a drug trafficker. This is the story of a suspended moment between music, politics, and urban reality.

When Michael Jackson films with the barons of the favela

Rio de Janeiro, 1996. Spike Lee’s camera pans across the hills of Dona Marta, a favela clinging to the city’s slopes like a gaping scar on the face of an unequal Brazil. There, among crumbling walls, faces shine with excitement: Michael Jackson has come to shoot his video. But this setting, a far cry from Hollywood studios, is no ordinary set. Here, to film, one must first… negotiate with a trafficker.

The governor of Rio is against it. The police refuse to set foot in Dona Marta. And yet, the cameras roll. Because in the shadows of the official government, another power governs life in the neighborhood: Marcinho VP, drug lord and leading figure of the Comando Vermelho. That day, the King of Pop’s safety doesn’t rely on bodyguards—but on a pact with the local “boss.”

Between pop culture, urban geopolitics, and backroom deals, the video for They Don’t Care About Us reveals a long-silenced truth: in certain parts of the world, order does not come from above. It is negotiated.

Marcinho VP, the poet godfather of Dona Marta

His real name: Márcio Amaro de Oliveira. But in Santa Marta, no one ever called him that. Up there, on Rio’s steep hills, where staircases replace streets and asphalt disappears whenever the state turns its back, Marcinho VP was more than a name: he was a figure of authority, a living legend, a walking contradiction.

At just 24 years old, he already ruled one of the Comando Vermelho’s strongholds, the most powerful criminal faction in the city. Charismatic and ruthless, Marcinho had established himself in a world where hierarchy is carved in fear and cemented by weapons. But what set him apart from other “hill bosses” was a strange intellectual depth, almost unsettling for a man at war with the established order.

In Abusado, the monumental investigation by journalist Caco Barcellos, Marcinho appears as a near-literary character: he reads Nietzsche, questions the meaning of violence, quotes Che Guevara between tactical commands. His other nickname, Juliano VP, echoed a mythical poet-trafficker from a neighboring favela. To those close to him, Marcinho was an educated man in a brutal world—a strategist able to navigate the system’s hostility and the misery of everyday life.

But the intellectual sheen doesn’t erase the raw reality. Marcinho was also a manager of chaos. He maintained social peace in his own way: arbitrating neighbor disputes, funding community parties, distributing emergency aid. In the absence of public services, he was the one people turned to for a gas bottle or conflict resolution. A de facto authority, forged in illegality but tolerated (even respected) because it filled the void left by institutions.

So when Michael Jackson arrives in Rio to shoot in a favela, it’s not the mayor or the governor who has the final say—it’s Marcinho VP. The man hunted by police is also the one who ensures the King of Pop’s safety. An irony that, in Brazil and beyond, reveals a deeper truth: in the margins, governance doesn’t always look the way we think.

Tense shooting

This isn’t a movie scene. It’s not an urban thriller. It’s a very real story, caught somewhere between the surreal and the tragically ordinary: the story of a video shot like a diplomatic mission, in a territory the state itself no longer dares to enter.

In 1996, Michael Jackson wants to give visual weight to They Don’t Care About Us, his protest song against racism, police brutality, and the neglect of minorities. A punchy, politically charged track. And what better setting than a Brazilian favela to match the song’s intensity? In Rio, he chooses Dona Marta—not for its exoticism, but because it embodies the structural violence he sings about.

But reality quickly sets in. The governor of Rio is staunchly opposed. Brazil is still dreaming of hosting the 2004 Olympics—there’s no way they’ll let the world see what’s hidden behind the postcard beaches. Show the poverty? The drugs? The bullet-ridden walls? That would be bad PR. So the state does what it often does in such zones: it backs down.

But Spike Lee steps forward. And he does what the authorities no longer dare: he speaks with the real decision-maker. The name is well known: Marcinho VP. The hill’s baron. The Comando Vermelho boss in Santa Marta.

The deal is clear. No money changes hands, no under-the-table bribes. Just a tacit agreement: Michael and his team can film, as long as the favela stays calm. In return, the neighborhood receives equipment, visibility, respect. And Marcinho keeps his word. For three days, Dona Marta becomes a pacified enclave, secured by the traffickers’ men. Not a single shout. Not a single gunshot. Just music. And children dancing with Michael, smiling between crumbling walls.

Spike Lee would later say a sentence that still stings like a slap in the face of the world:

“For three days, Dona Marta was the safest place on earth.”

Biting irony: it’s not the police protecting the world’s biggest star, but a trafficker. It’s not the state ensuring safety, but the unofficial “king” of a forgotten territory. From this absurd situation came a global music video, now symbolic of a dual truth: the fight against oppression is universal—but its implementation often depends on invisible or illegitimate powers.

Michael, Marcinho, and the favela: Three faces of a single cry

Some images leave a lasting mark. Michael Jackson in a white t-shirt, surrounded by barefoot children dancing on the hills of Dona Marta, is one of them. But beneath the shared emotion lies a much more complex web of symbols.

Michael Jackson is not just a pop star—he is a hyper-exposed Black body, long distorted by spotlights and surgery, yet in 1996, he chooses to return to his roots: to loudly speak about the neglect of his people. They Don’t Care About Us isn’t a commercial track. It’s a manifesto, a universal cry against racial brutality, systemic violence, and the silence of the powerful. That day, by singing those words in the heart of a favela, he maps African American pain onto a global landscape of oppression.

Facing him, invisible yet omnipresent, is Marcinho VP. He doesn’t dance. He doesn’t sing. He doesn’t appear in the video. Yet without him, none of it would have happened. He’s the one who made the shoot possible—not out of naïve humanitarianism, but because he (in his own way) understood the impact of the image. In his world, providing peace for three days is a show of strength. But it’s also a symbolic act: the outlaw becomes the guardian, the outcast becomes the mediator. A disturbing role reversal—but a very real one.

And then there are the residents. Those we see on screen, smiling, vibrant, proud. For them, Michael’s visit wasn’t a pop star’s whim—it was history. A validation. A fragment of dream crashing onto their concrete. Pop culture no longer looked at them from afar—it came to their doorstep. In 2010, a statue of Michael Jackson was unveiled in Dona Marta. Not by the state. By the residents.

This triangle—Michael, Marcinho, the people—encapsulates all the ambiguity of that moment. A global star, a philosopher-trafficker, a forgotten yet dignified community. Three figures who, for a few days, wove together an unexpected narrative. A global cry, a local peace, and a truth that disturbs: sometimes, it’s the margins that rewrite the center.

When pop culture meets the parallel order

The shoot of They Don’t Care About Us in Dona Marta wasn’t just a publicity stunt. It was a suspended moment—almost unreal—when global culture burst into a grey zone, forgotten by the state but governed by its own codes. Michael Jackson, a global icon with a universal message, found resonance in a territory ruled not by law, but by another power: that of a local anti-hero, Marcinho VP.

What happened there wasn’t just the making of a video. It was a lesson in urban geopolitics. In the margins of Global South metropolises, it’s often necessary to negotiate with those labeled “outlaws” to ensure security, stability—even peace. And when Spike Lee’s camera started rolling, it captured that paradox: a world of blurred rules and inverted roles.

The real question, ultimately, is this: who truly governs the margins? When the state retreats, when police repress, when justice no longer reaches the hills, others step in. And sometimes, those deemed enemies by society become the de facto managers of daily life.

Between pop culture, politics, and shadow governance, Michael Jackson’s video remains a symbol of this hybrid reality—where hope rubs shoulders with illegality, and art touches the very nerve of truth.

References

- Barcellos, C. (2003). Abusado: O dono do Morro Dona Marta. São Paulo: Editora Globo.

- Okayplayer. (2015, June 4). Spike Lee reveals 5 things you didn’t know about his music videos.

- Tampa Bay Times. (1996, February 14). Rio officials still angry over Jackson visit.

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Márcio Amaro de Oliveira. Wikipedia.

- Rocha, C. (2015). Poder paralelo e legitimidade local nas favelas cariocas. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Table of Contents

- When Michael Jackson Films with the Barons of the Favela

- Marcinho VP, the Poet Godfather of Dona Marta

- Tense Shooting

- Michael, Marcinho, and the Favela: Three Faces of a Single Cry

- When Pop Culture Meets the Parallel Order

- References