Vincent Ogé, often relegated to the margins of the Haitian Revolution, was nevertheless one of the first to challenge the colonial racial order. A reformist mulatto bourgeois, slave owner yet victim of the system, he embodies a complex, hybrid, and tragic figure. This historical investigation retraces the path of a man who, without seeking independence, paved the way for the Black revolution.

Between privilege, betrayal, and political martyrdom

Vincent Ogé. A name that barely echoes in the collective memory of contemporary Haiti. Neither fully hero nor entirely traitor, he occupies a shadowy zone in the grand narrative of the Haitian Revolution. A free man of color, wealthy mulatto merchant, educated in the metropole, who rejected legal submission but not the colonial order. A man too progressive for the white elite, too cautious for the enslaved rebels. A figure crushed by the contradictions of his time.

Born in the heights of Dondon, at the heart of a slave-based society stratified by color and wealth, Ogé represents this in-between bourgeoisie: ambitious yet constrained, freed yet never equal. His 1790 action—raising an armed force to enforce the French law granting civil rights to free people of color—was both bold and tragically incomplete. Rejecting both the revolutionary violence of the enslaved and the resignation of the free, Ogé attempted an impossible compromise, which ended with his capture, being broken on the wheel, and the public display of his head.

Why exhume this figure, long marginalized by both colonial and postcolonial history? Because he reveals something deeply disturbing about the racial, social, and political dynamics in the French colonies. Because he embodies the fate of a Black elite seeking integration into a system history demanded be destroyed. In short, Vincent Ogé was not a revolutionary, but a symptom: of a creole order in decomposition, in search of an impossible equality within a world built on inequality.

An heir without illusions (wealth, caste, and color)

Born around 1755 in the fertile hills of Dondon in the colony of Saint-Domingue, Vincent Ogé entered a world where racial hierarchy governed every gesture, every breath, every destiny. The son of a wealthy white planter and a prosperous freed Black woman, he belonged to a specific caste known as the “free people of color”: neither slaves nor equals, but whose wealth allowed for hope.

His childhood was marked by material comfort. His mother, a freedwoman from a lineage of wealthy mulattoes, owned land and slaves. Young Vincent grew up on a plantation where Black authority coexisted with the subjugation of other Blacks—a daily paradox that seemingly did not trouble his young Creole consciousness. It was not revolt that shaped him, but a quest for recognition.

Early on, he was sent to Bordeaux, the capital of Atlantic trade, to learn the goldsmith’s craft. There, he absorbed the codes of the French bourgeoisie, frequented Masonic lodges, and discovered Enlightenment ideals—without ever renouncing the colonial order. Ogé was not anti-European: he was a brown-skinned European, a Creole demanding to be judged on merit, not color.

Back in Saint-Domingue in the 1780s, he settled in Cap-Français, the colony’s economic capital. He became a successful merchant and a prominent social figure. He owned several slaves, managed thriving businesses, and reached the pinnacle of the colored bourgeoisie. Yet his rise hit an invisible ceiling: he could not vote, be elected, or sit in colonial assemblies. He paid taxes but had no voice. Ogé realized that wealth would never redeem his race.

By the late 1780s, Ogé’s social ascent was halted by two barriers: the legal limits of his status as a “free man of color,” and a series of economic setbacks entangling him in family lawsuits. Indebted and weakened in Cap-Français, he chose to leave the colony. This departure was not yet political exile—it was a cautious retreat that would, despite himself, ignite a revolutionary fate.

Arriving in Paris at the dawn of the French Revolution, Ogé found himself swept into an ideological whirlwind. He discovered the fervor of political clubs, the ferment of pamphlets, and most notably: the Society of the Friends of the Blacks, founded by Brissot and Clavière to promote the abolition of the slave trade. Ogé was not (yet) an abolitionist, but he mingled with intellectual and legal circles challenging colonial norms.

In this context, he met Julien Raimond, another mulatto from Saint-Domingue, older and more politically structured. Together, they formed an unlikely duo: Ogé, the Creole bourgeois concerned with respectability, and Raimond, the republican lawyer with progressive ideals. But their shared goal was clear: to enforce the principles of 1789 in the colonies—at least for men like themselves. They were not yet speaking of slavery. They spoke of civic equality for the free people of color—“citizens without rights” who, despite wealth and loyalty to France, remained excluded from colonial citizenship.

It was this legal (not yet revolutionary) consciousness that forged Ogé’s new commitment. He believed in law, in the National Assembly, in the universalism proclaimed by the Declaration of the Rights of Man. This would be his strength—and his tragedy: to believe that racism could be defeated by procedure, and colonial domination by diplomacy.

1790: The Ogé year (Between uprising and illusory reform)

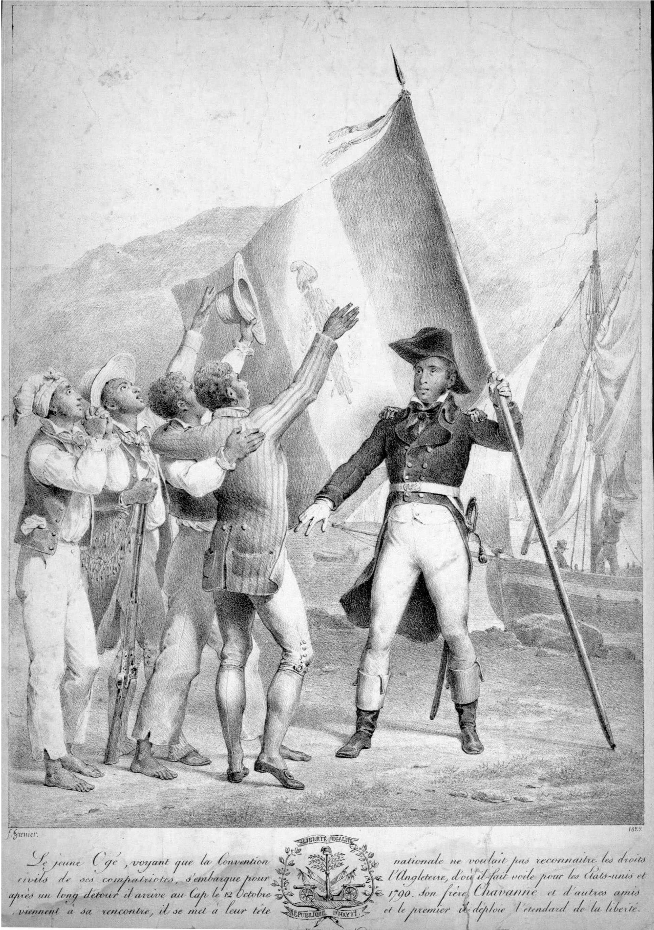

In the autumn of 1790, Vincent Ogé secretly landed on the shores of Saint-Domingue, after a discreet journey via London and Charleston. He did not return as a conqueror or even a fugitive, but as a self-proclaimed emissary of the French Revolution. From Paris, he had secured the May 15 decree from the National Assembly granting civil equality to “all free men born of free parents” in the colonies. In his mind, the battle was won—only enforcement remained. He returned not as an insurrectionist, but as a legal envoy. At least outwardly.

Upon arrival in Cap-Français, Ogé sent a formal letter to Governor Blanchelande, demanding immediate application of the decree. His letter, polite yet firm, carried the tone of a legal ultimatum. He presented himself as the legitimate representative of free people of color and implicitly threatened force if refused. To a white colonist, this was an act of subversion. To Ogé, it was a test of the republic’s promise.

Blanchelande stalled, deferred, refused to act without direct instruction. The colonial administration feared the domino effect: enforcing the decree for Ogé and his peers meant opening the door to the collapse of white power. Ogé, meanwhile, quickly realized that the legal arena alone would not suffice. He quietly recruited around a hundred armed men, all free men of color, all determined to make the governor yield.

From that moment, Ogé’s image shifted: from loyal citizen to rebel. Yet it was a rebellion without a people, without a real social base, and without strong military support. Strategically insignificant, his initiative was politically explosive. It revealed a man trapped by his own republican idealism, believing that a law passed in Paris could dismantle three centuries of racial order. At that precise moment, Vincent Ogé was neither revolutionary nor soldier—he was a diplomat of the impossible, still believing that words weighed more than weapons.

Vincent Ogé did not speak for the enslaved. He gave no speeches to them, did not advocate their liberation, and saw their condition more as a matter to stabilize than a system to overthrow. And yet, his public execution became a signal. His torture—broken on the wheel in Cap-Français’ public square in February 1791—displayed the mulatto body as a reminder of white inflexibility. In a colony where Black humiliation was routine, seeing a free, wealthy, educated man executed like a common criminal shattered a social taboo: there could be no dialogue between races so long as color prevailed over law.

The psychological impact of this execution cannot be measured in words but in tense silence. Just months later, in August 1791, the massive slave uprising erupted in the North. Boukman, a Vodou priest, gave the spiritual signal; plantations burned, masters fled or fell. Ogé was never cited, but his failure hovered over the fury of the insurgents. Where he had negotiated equality, they demanded the outright abolition of slavery. The shift from reformism to radicalism occurred between his wheel and their machetes.

Toussaint Louverture, Biassou, Jean-François, and later Dessalines—none claimed Ogé as a guiding figure. The gap was too wide. Ogé embodied a mulatto elite seeking to join the ranks of the masters, not to overthrow them. Black leaders, often former slaves or maroons, spoke a different language: one of revenge, emancipation, rupture. Ogé thus became a martyr out of place; occasionally instrumentalized, but never truly reclaimed.

Yet his fate acted as a first crack. It proved that even the most assimilated, the most polished, the most “deserving” men of color would never be admitted to the colonial Republic. The enslaved grasped this truth—and their demands radicalized. Ogé did not want the revolution. He made it inevitable.

A forgotten link between mulatto elites and the black masses

Vincent Ogé did not dream of a new world. He sought to correct an imbalance, not abolish a system. This crucial nuance makes him a reformist rooted in the logic of slavery—not a revolutionary in the full sense. He was not an enemy of the colonial order; he was a refined product of it, and at times, a beneficiary.

Like many free people of color in Saint-Domingue, Ogé himself owned slaves. He exploited, traded, administered. He did not question the legitimacy of the slave trade or the plantation economy. What he rejected was civic humiliation, legal exclusion, and the denial of recognition to men like him—wealthy, educated, loyal to France. His struggle was for access to citizenship, not the condition of slavery.

In this, he embodied the fundamental contradiction of the mulatto elite: aspiring to assimilate into the dominant order while remaining objects of its contempt. Demanding rights in the name of universalism while practicing daily exploitation. Ogé was not a traitor to the enslaved—he simply did not identify with them. He lived in a gray zone, between the whites he wished to join and the Blacks he refused to represent.

His (tragic) error was believing that the France of the Enlightenment, amid revolution, would heed the voice of a man of color from the colonies. But the fledgling Republic needed sugar more than equality, and Ogé became the living illustration of the racial ceiling that even wealth could not break.

That is why he died with no immediate political legacy. Neither a hero to the whites nor a father to the enslaved, he was crushed between two camps, two visions, two peoples. A victim, yes—but of a system he served more than he fought.

Vincent Ogé did not speak for the enslaved. He gave them no speeches, did not fight for their liberation, and viewed their condition more as something to be stabilized than overturned. And yet, his public death became a symbol. His torture, inflicted by the wheel in Cap-Français in February 1791, displayed the mulatto body as a warning of white inflexibility. In a colony where Black humiliation was routine, to see a free, rich, educated man executed like a common criminal shattered a social taboo: there could be no dialogue between races as long as color outweighed law.

The psychological impact of this execution cannot be measured in words but in the tense silence that followed. Months later, in August 1791, the general slave insurrection exploded in the North. Boukman, a Vodou priest, gave the spiritual signal; plantations went up in flames, masters fled or were killed. Ogé is never mentioned, but his failure hovers over the insurgents’ fury. Where he negotiated equality, they demanded the outright end of slavery. The shift from reformism to radicalism happened between his wheel and their machetes.

Toussaint Louverture, Biassou, Jean-François, and later Dessalines—none adopted Ogé as a tutelary figure. The gap was too great. Ogé represented a mulatto elite that sought to join the masters’ ranks, not overthrow them. The Black leaders, often former slaves or maroons, spoke a different language—one of revenge, emancipation, rupture. Ogé thus became a misfit martyr—occasionally instrumentalized, but never truly claimed.

Yet his fate acted as a first fissure. It proved that even the most integrated, the most refined, the most “worthy” men of color would never be accepted into the colonial Republic. That truth, understood by the enslaved, radicalized expectations. Ogé did not seek the revolution. He made it inevitable.

Posterity and appropriations

Haitian history, like all post-revolutionary memory, has its heroes, its martyrs—and its ghosts. Vincent Ogé belongs to the latter category, nestled in the interstices of a national narrative that has alternately sanctified, ignored, but rarely understood him. His memory was less a legacy than a symbolic battleground, where social classes, skin tones, and political visions clashed over the corpse of a man who became an emblem despite himself.

In the 19th century, under republican regimes led by light-skinned elites (Alexandre Pétion, Boyer, later Geffrard), Ogé was elevated to the rank of precursor hero, a paragon of an enlightened and sacrificed colored bourgeoisie. Streets were named after him, his remains occasionally invoked as relics, and his actions rewritten—not as reformist and legalist, but nearly revolutionary. This recovery sought to build a mulatto pantheon to rival radical Black figures like Dessalines or Christophe.

But this veneration was soon challenged. Starting in the 20th century, with the rise of more assertive Black nationalism, Ogé became suspect. Haitian historiography influenced by indigénisme, political noirisme, and post-colonial critique (Jean Price-Mars, Jacques Roumain, later Michel-Rolph Trouillot) questioned Ogé’s centrality. He was reread as a man of order, a slave owner, a bourgeois disconnected from the people. For some Black intellectuals, he embodied class betrayal—seeking equality for his own while ignoring the enslaved masses. For others, more nuanced, he remains a tragic figure: clear-eyed yet trapped, visionary yet limited by his era.

Even today, his name divides. He lacks the popular fervor of a Toussaint, the brutal radicalism of a Dessalines. He floats between two competing memories: that of the mulattoes who honor him as a political ancestor, and that of the Black masses who cannot identify with a man who never included them in his struggle. Ogé’s memory, like his life, is a boundary: fine, sharp, and never fully crossed.

While Haitian memory of Vincent Ogé has been marked by ambivalence, the Black diaspora and Pan-African thinkers have sometimes seen in him a forgotten figure of early Atlantic Black consciousness, a precursor bridge between the Enlightenment and emancipation.

As early as 1853, African-American intellectual George Boyer Vashon, one of the first Black lawyers in the U.S., wrote a poem dedicated to Ogé. He drew a striking parallel with Toussaint Louverture, portraying Ogé as a martyred forerunner of the Black general: “Thy blood was seed; from it arose / A nation’s manumission!” For Vashon, Ogé was not a class traitor, but an initiator, an awakener, whose tragic failure opened the path to total revolution. This reading, rooted in militant American abolitionism, gave Ogé the dignity of a spiritual ancestor—more symbolic than political, but foundational.

In later decades, that interpretation faded under the rising shadow of more radical Black figures. But since the 21st century, a few voices from Antillean, Creole, and Francophone Pan-Africanist circles have rehabilitated Ogé as a pioneer of bourgeois Black consciousness. Though limited in his social horizon, he is seen as innovative in his use of law, diplomacy, and political strategy. He is viewed as the first to bring a Black demand for legal equality to the colonial stage—a paradigm that would reappear later in Francophone Africa’s anti-colonial struggles or in Afro-Caribbean descendants’ claims.

Above all, Ogé becomes legible again in light of the tension between inclusion and rupture, between reform and revolution. He represents a direct historical link between the French Revolution and future decolonial struggles—not as a charismatic hero, but as a missing link, one who tried conciliation before the world tipped into revolt.

In an era where nuanced, unsettling, in-between figures are regaining visibility, Ogé returns not as a role model but as a question: what do we do with those who neither betrayed nor saved, but tried to negotiate in a world where compromise was no longer possible?

The revolutionary despite himself

Vincent Ogé did not want to shatter the world. He wanted to reform it from within—with words, with law, with the principles of the Enlightenment as his banner. Yet it was his fall that triggered the collapse of a three-century-old system. By demanding rights for his kind (the free people of color) without challenging slavery, he unwittingly opened Pandora’s box. For in a society built on racial hierarchy, to demand a right is already to undermine the entire edifice.

Ogé was the first to publicly break from colonial submission—without yet dreaming of independence. He still believed in the king, the Republic, in France. He was neither a rebellious slave nor a decadent master, but a man between two worlds, whose struggle revealed the impossibility of compromise. He was rejected from both sides: too Black for the whites, too white for the Blacks. Yet it is precisely in that liminal, uncomfortable, tragic position that his historical power lies.

He neither overthrew the colonial order nor freed the slaves. He simply proved that reform was impossible. The Black revolution may have started there—not in a cry of revolt, but in the reasoned failure of a man of law. Ogé is not a universally celebrated hero—and that’s a good thing. He forces us to think of History without simplism, without manichaeism. He is the living fracture of a world at its breaking point.

Sources

Garrigus, John D. Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in French Saint-Domingue. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Fick, Carolyn E. The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below. University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

Popkin, Jeremy D. You Are All Free: The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Geggus, David P. The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History. Hackett Publishing, 2014.

Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Harvard University Press, 2004.

Madiou, Thomas. Histoire d’Haïti. Port-au-Prince, 1847–48.

Table of contents

- Between Privilege, Betrayal, and Political Martyrdom

- An Heir Without Illusions (Wealth, Caste, and Color)

- 1790: The Ogé Year (Between Uprising and Illusory Reform)

- A Forgotten Link Between Mulatto Elites and the Black Masses

- Posterity and Appropriations

- The Revolutionary Despite Himself

- Sources