Born in 1944 in Birmingham, at the heart of segregated America, Angela Davis made her life into a school of resistance. A Marxist philosopher, Black Power activist and early feminist, she experienced life on the run, prison, fame, and exile—without ever renouncing her thinking. From the classroom to the courtroom, from American universities to the podiums of the United Nations, she transformed struggle into method and thought into a weapon. Still today, her name embodies the rare alliance between intellectual rigor, political courage, and a universal quest for justice.

The Face of the struggle

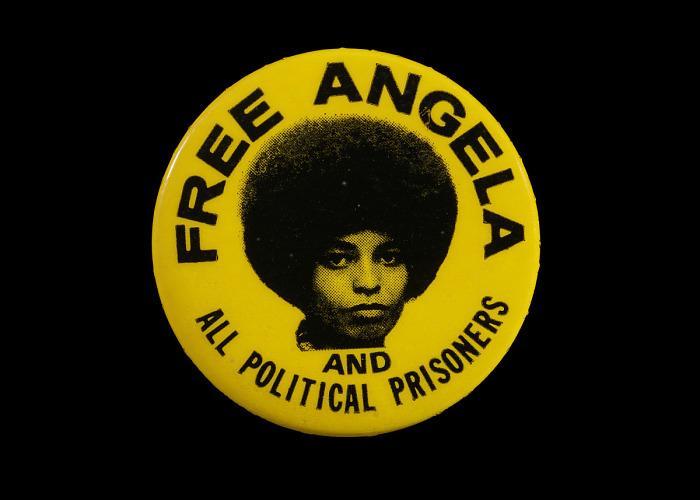

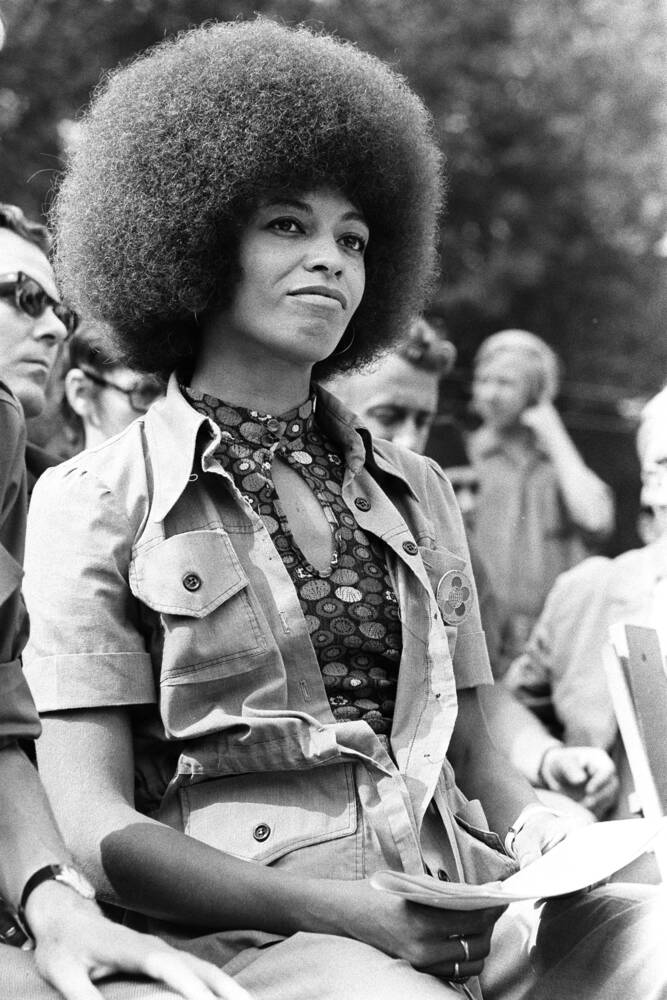

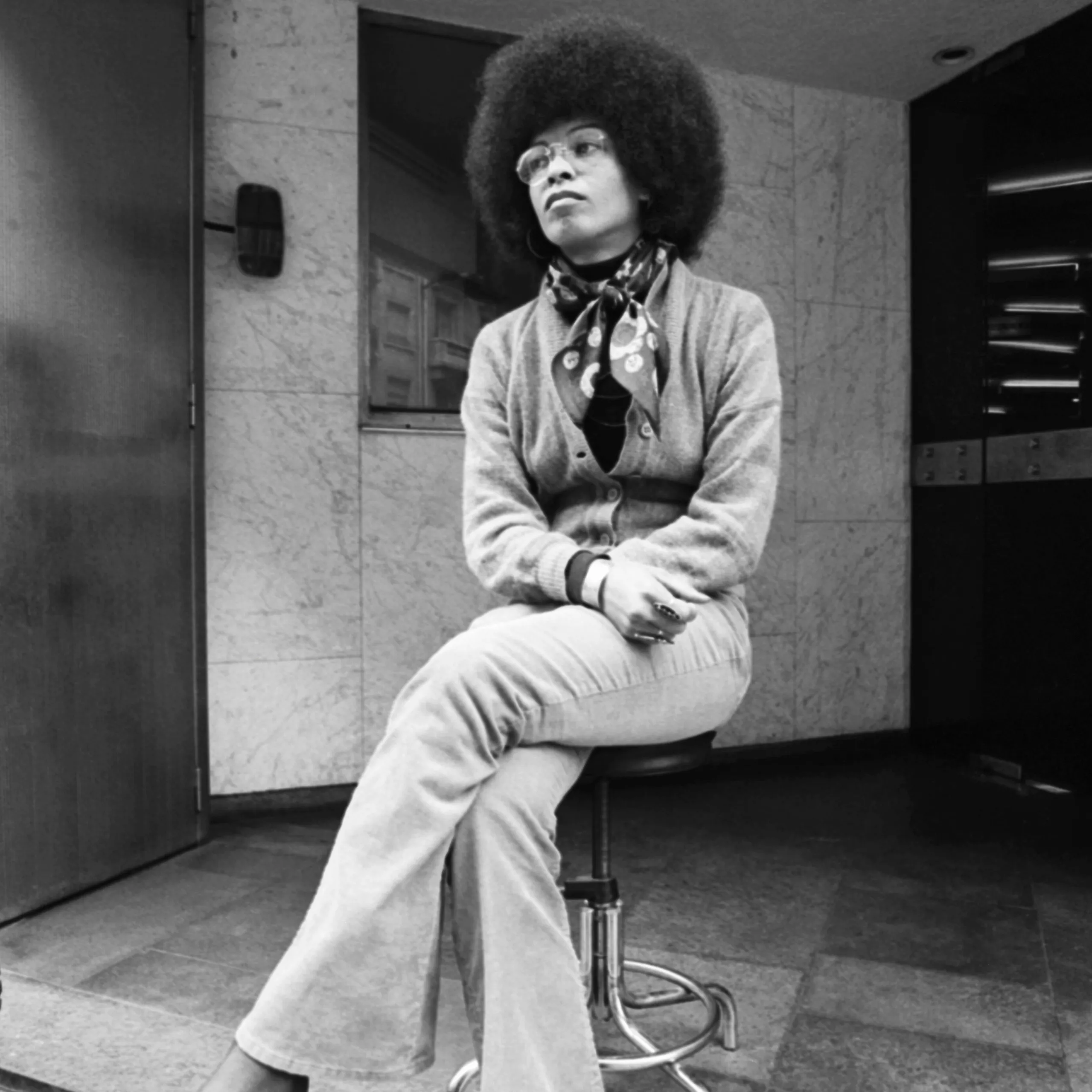

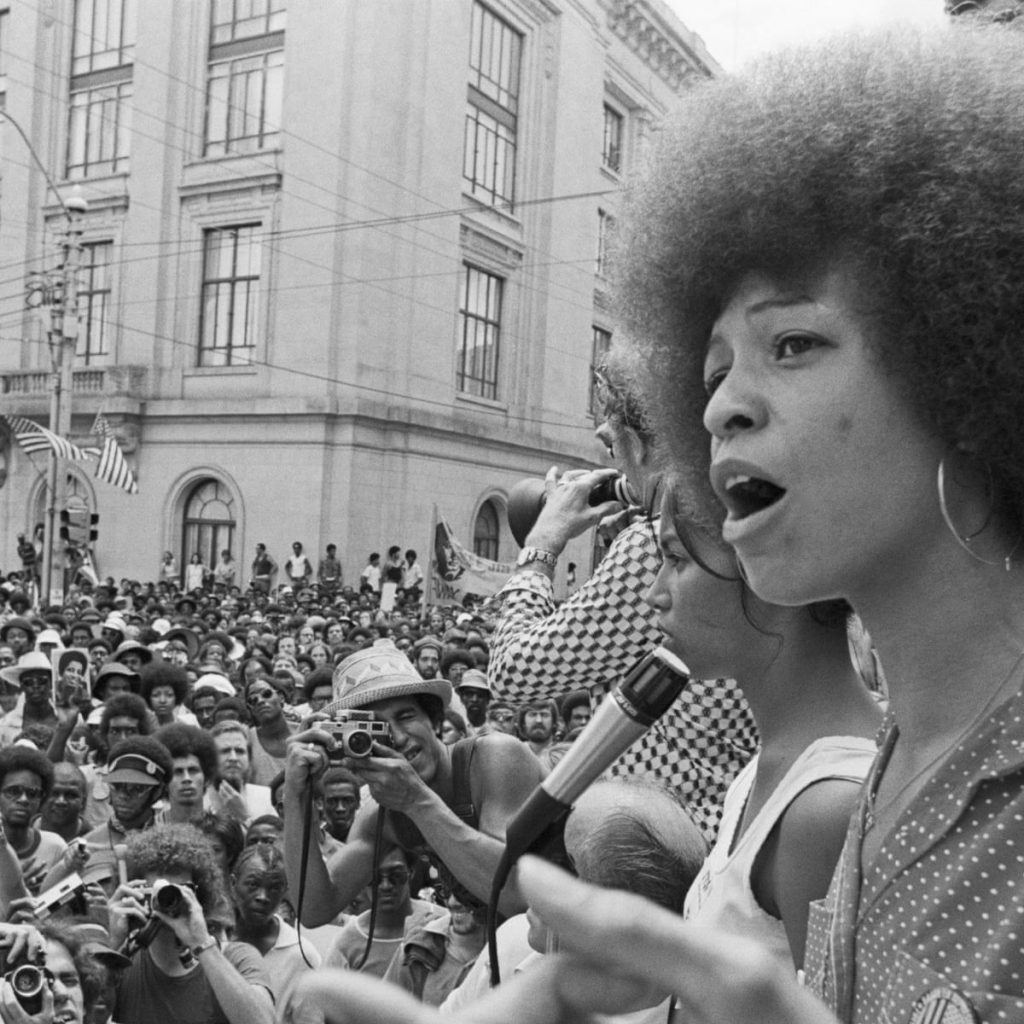

San José, 1972. In front of the courthouse, a sea of raised fists chants a name that has become a symbol: “Free Angela!”. A young Black woman with an afro walks between two rows of police officers, her gaze steady, calm, impassive. Angela Davis has just been acquitted after sixteen months of detention and an international media manhunt. She has not only won a trial: she has entered History.

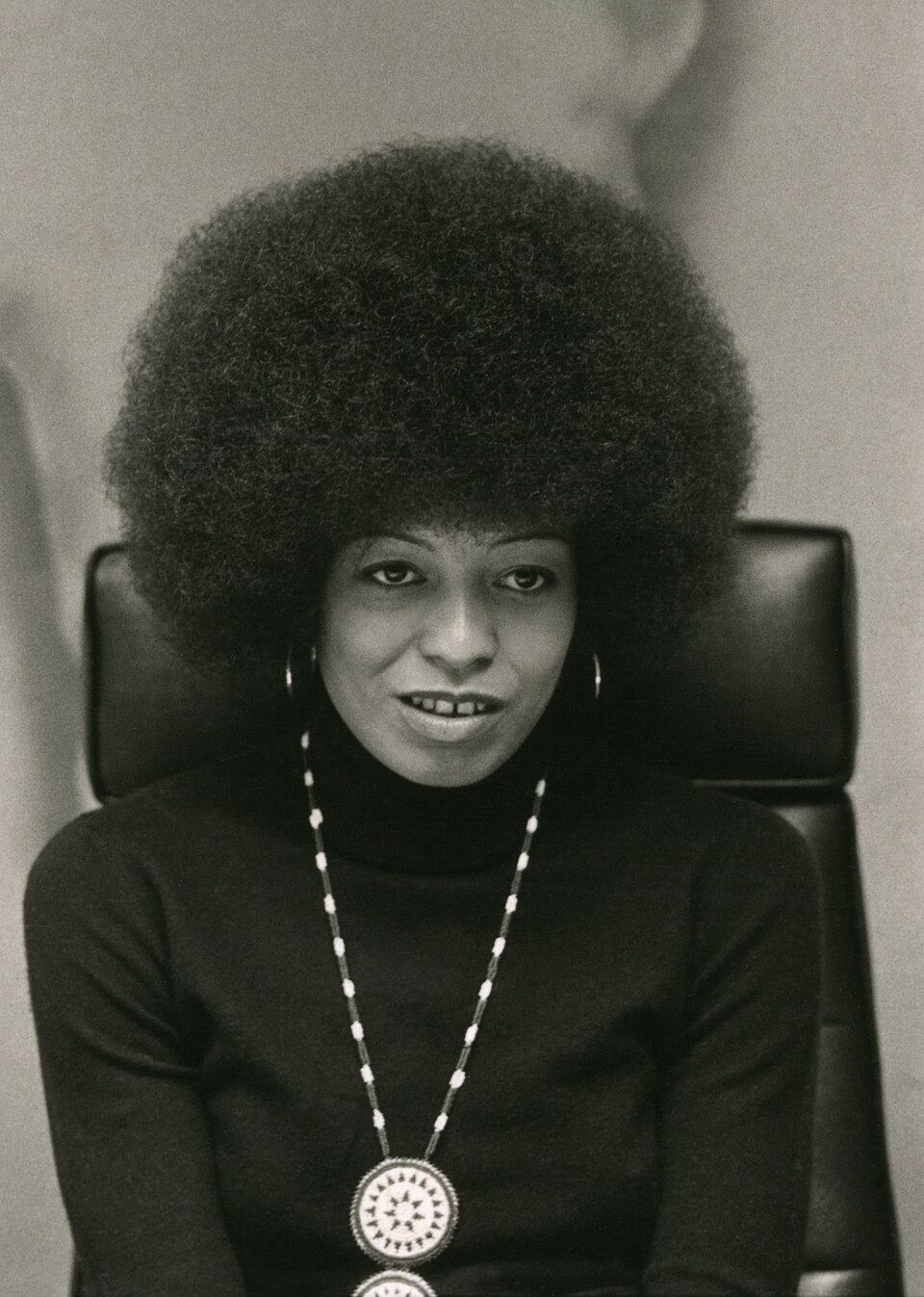

Philosopher, activist, professor, prisoner, icon—Angela Davis embodies half a century of struggles: those of Black people, of women, of workers, and of prisoners. Her face, printed on posters across the world, represents far more than a person: an idea. The idea that thought can be a weapon, that freedom is conquered through knowledge and action.

But behind the icon lies a complex path: that of a Marxist intellectual, born in the segregated South, trained in German rigor, forged by American violence. How did this child of Birmingham become a universal conscience? How did a scholar turn philosophy into revolutionary praxis?

To understand Angela Davis, one must follow a trajectory where three lines of fire converge: race, gender, and class. Three wounds, three battlegrounds. Three axes of the same revolt: to think of freedom not as an ideal, but as a duty.

Angela Davis: black icon, feminist, and committed revolutionary

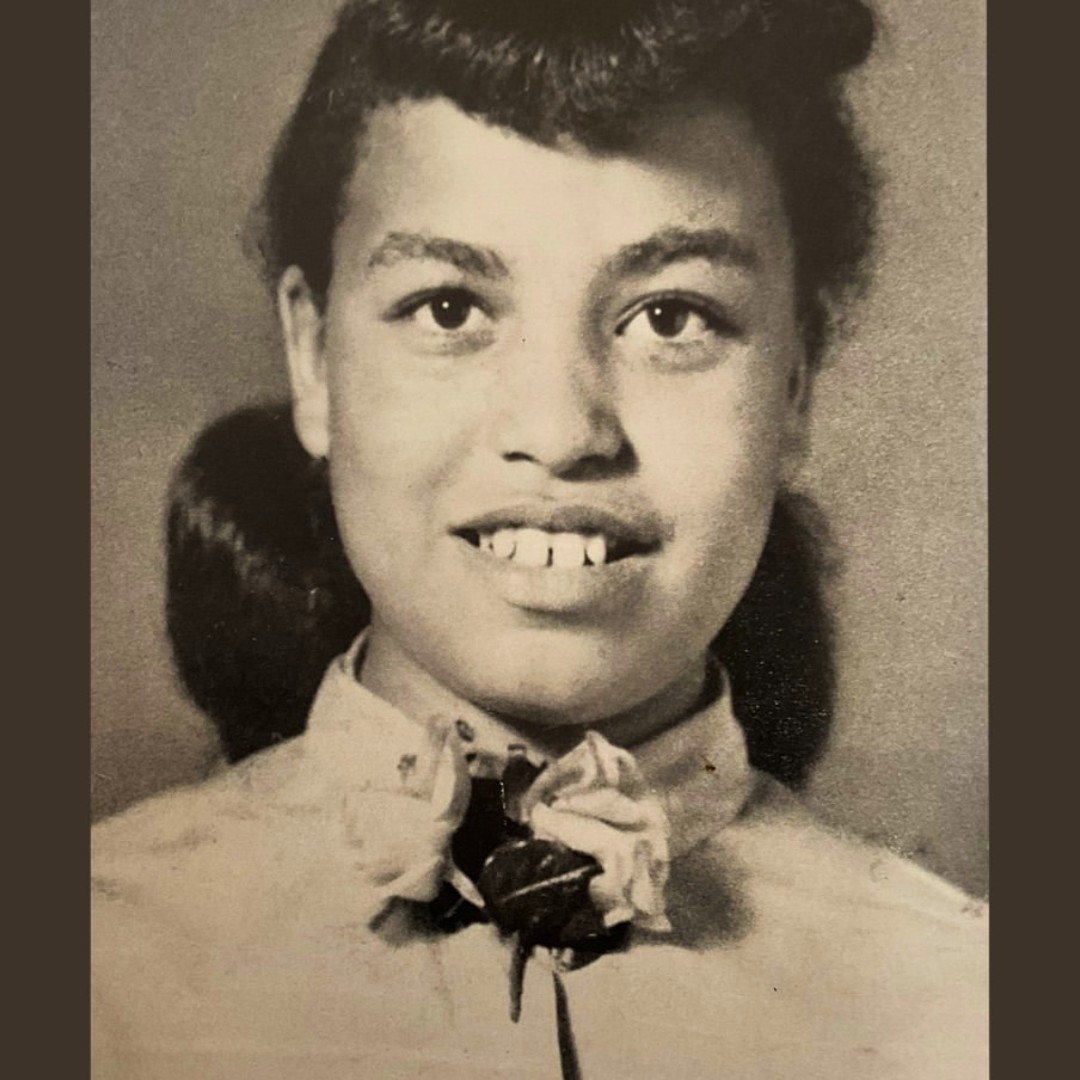

Angela Yvonne Davis is born on January 26, 1944, in Birmingham, Alabama, in an America still marked by Jim Crow laws. Her neighborhood, nicknamed “Dynamite Hill,” earns its name: explosions from the Ku Klux Klan regularly target Black families who dare to settle in “white” areas. The child thus grows up between the laughter of family meals and the rumbling of racial hatred.

Her parents, Frank and Sallye Davis, belong to the educated Black middle class. The father is a teacher turned gas station owner; the mother, a schoolteacher, is a militant of the Southern Negro Youth Congress, one of the few progressive movements in the American South. In the Davis household, politics is discussed at the table. One reads, debates, learns—not to please, but to survive.

Angela discovers the face of violence very early. At nine, she sees neighbors lynched. At nineteen, she mourns the four young girls killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, a tragedy that occurred a few blocks from her home. These events engrave in her a certainty: racism is not an individual error, it is an organized system.

Segregation, paradoxically, offers her a school of consciousness. She learns that resistance begins with self-knowledge. And that, faced with domination, thought is a form of defense.

At seventeen, Angela leaves the South to enroll at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. There she discovers another world: that of a liberal, intellectual, mostly white America. But the brilliant Black student first feels like a stranger. She finds refuge in books (Hegel, Marx, Kant) and in the seminars of a charismatic professor: Herbert Marcuse, a Marxist thinker of the Frankfurt School.

Marcuse becomes her mentor, the one who teaches her to connect theory and praxis. Under his influence, Angela understands that philosophy cannot be reduced to abstraction: it must question power relations, social structures, and living conditions.

Thanks to a scholarship, she goes on to study at the Sorbonne, then in Frankfurt, in the full effervescence of the 1960s. West Germany, then in intellectual reconstruction, is a critical laboratory: the youth challenge capitalism, the Vietnam War, and consumer society. Angela becomes even more politicized. She reads Marx and Engels in the original, frequents Maoist circles, discovers European feminism and anti-colonial struggles.

Returning to the United States, she brings back a conviction: the liberation of Black people cannot be considered without a global transformation of the economic and patriarchal system. She wants to teach philosophy, but a committed philosophy—a philosophy of struggle.

At 25, Angela Davis becomes an assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Her appointment triggers scandal: it is discovered that she is a member of the American Communist Party and close to the Black Panther Party. Under pressure from governor Ronald Reagan, she is dismissed.

But the damage is done: her name circulates, her lectures draw crowds. She embodies the fusion of two worlds: intellectual rigor and urban revolt. She speaks of Marx and Malcolm, of Lenin and Luther King, of economic exploitation as the root of racism.

Her membership in the Che-Lumumba Club, an African-American section of the Communist Party, puts her under FBI surveillance. Yet her discourse remains peaceful: she wants to arm consciences, not bodies. For her, knowledge must become a lever for transformation.

In post-1968 America, Angela Davis becomes a bridge between the university and the street. She represents a generation of Black intellectuals who refuse the dilemma between integration and radicality. Her method is simple: think in order to act, act in order to think.

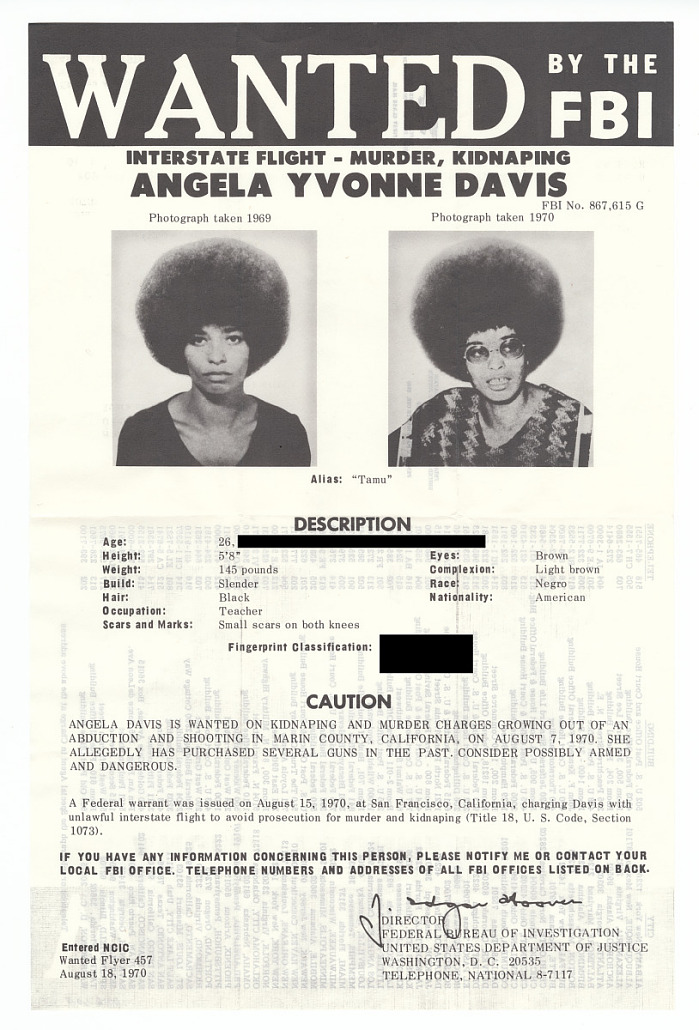

History shifts on August 7, 1970. Jonathan Jackson, the young brother of Black militant George Jackson, attempts to free three prisoners (the “Soledad Brothers”) by taking hostages in the courthouse of Marin County, California. The operation turns tragic: four dead, including the judge.

The weapons used are registered in the name of Angela Davis. The FBI immediately issues a warrant for her arrest for “conspiracy, kidnapping, and murder.” She flees, becomes the most wanted woman in America, and is arrested two months later in New York.

Her 1971 trial becomes a global event. “Free Angela” committees form in Paris, Algiers, Moscow, Accra. The Rolling Stones, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and Miriam Makeba dedicate songs to her. She faces the death penalty.

But after sixteen months of detention, the verdict drops: full acquittal. The world holds its breath. The young professor leaves prison, fist raised, triumphant smile. The image travels the world: that of a Black woman who defied the American state and survived.

Angela Davis becomes a global icon, not by choice, but by necessity. She never wanted to be a heroine; she became a symbol.

Freed, Angela Davis launches into an international career. She travels to Cuba, the USSR, East Germany, Czechoslovakia. She is welcomed as a heroine of the anti-imperialist struggle. In 1979, she receives the Lenin Peace Prize in Moscow.

Her Marxist commitment places her at the heart of Cold War ideological debates. In the West, she is criticized for her proximity to communist regimes; in the East, she is admired as the incarnation of humanist socialism. Between the two, she carves her own path: that of an Afro-feminist anti-capitalism.

Back in California, she resumes teaching at San Francisco State University, then at UC Santa Cruz. Her courses attract students and activists. She develops a pedagogy of emancipation: the university as a place of contestation.

Angela Davis thus becomes a complete intellectual: professor, activist, writer, and witness of the century. She connects Marx to the street, Fanon to prison, Hegel to Harlem.

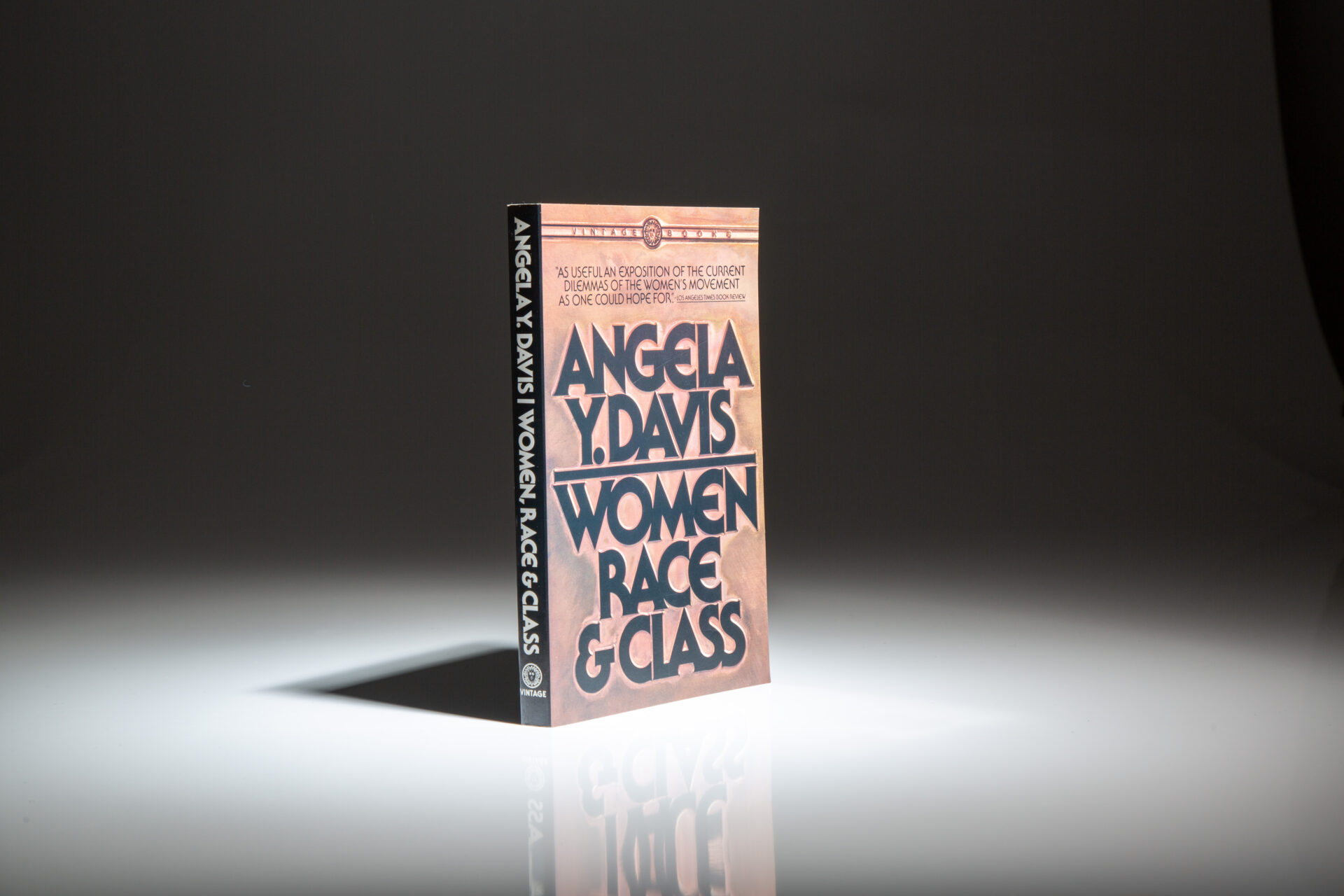

In 1981, her major work appears: Women, Race and Class. She develops a revolutionary idea: feminism, if it ignores race and class, is nothing but white privilege. For Davis, the oppression of Black women cannot be reduced to either sexism or racism, but to their intersection. Long before the word “intersectionality,” she formulates its logic.

She reminds readers that Black women were the first forced laborers, the first exploited, the first resistors. Their struggle aims not only at gender equality but at repairing structural inequalities.

This vision will deeply influence global feminist thought, from bell hooks to Kimberlé Crenshaw. In Reagan’s America, dominated by neoliberalism and conservative morality, Angela Davis embodies an intellectual counterculture: an inclusive, popular, anti-capitalist feminism.

From the 1980s on, Angela Davis concentrates her fight on the American prison system. She sees it as the historical continuity of slavery: the “prison industrial complex,” a network of economic interests exploiting Black bodies for profit.

In 1997, she co-founds the movement Critical Resistance, which advocates the abolition of prisons in favor of community and educational structures.

“Prisons do not protect society; they reflect it.”

Her analysis is grounded in history: after the abolition of slavery, vagrancy laws and forced labor transformed former enslaved people into prisoners. Today, African Americans—13% of the population—represent more than 40% of inmates.

Davis makes the prison the mirror of racial capitalism. She demonstrates that freedom is not only a legal question, but an economic one. And that no democracy can survive mass incarceration.

From the 2000s onward, Angela Davis becomes a key witness of contemporary struggles. She supports Occupy Wall Street, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the Women’s March of 2017. Her face reappears on posters, her quotes circulate on social media.e mouvement Black Lives Matter, et la Women’s March de 2017. Son visage réapparaît sur les pancartes, ses citations circulent sur les réseaux sociaux.

In 2019, a controversy erupts: the city of Birmingham (her hometown) withdraws and then restores an honorary distinction because of her support for the Palestinian people. Davis remains faithful to her principle: the universality of struggles.

“Freedom is indivisible. One cannot claim a part of it and refuse the rest.”

In 2025, she receives an honorary doctorate from the University of Cambridge—a late but symbolic recognition. At 81, Angela Davis continues teaching, publishing, demonstrating. Her voice, deep and steady, remains that of a living philosophy.

The work of Angela Davis transcends her era. She connected major critical traditions (Marxism, feminism, anti-racism) into a coherent and accessible thought.

She proved that a Black woman could be at once a theorist, activist, and moral figure without betraying herself. Her legacy reads in universities, in music, in social movements. In hip-hop (Lauryn Hill, Tupac, Common), in literature (Toni Morrison, Chimamanda Adichie), in research (Crenshaw, Angela Y. Davis Institute).

For African and Afro-descendant youth, she embodies a rare model: a revolution that thinks. And in a world saturated with rapid opinions, her work reminds us that understanding is the first form of resistance.

The fire of thought

Angela Davis never sought celebrity. She only wanted to understand why some people are free and others not. But in seeking freedom, she became one of its faces.

From Birmingham to Berlin, from the cell to the classroom, her journey is one of continuity: thinking against domination. She turned philosophy into a tool of emancipation, activism into a method, and thought into a weapon.

“I do not seek freedom for myself alone. I want it for those forgotten in the world’s cells.”

This sentence, written fifty years ago, resonates today as a moral testament.

Angela Davis not only defended the oppressed: she restored meaning to freedom. And if her struggle continues to speak to us, it is because it asks the simplest and most urgent question: what will we do with our own conscience?

Notes and References

Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race and Class, Random House, New York, 1981.

Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete?, Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Angela Y. Davis, Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, Haymarket Books, 2016.

Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, Beacon Press, 1964.

Gérald Horne, Angela Davis: The Biography, Polity Press, 1994.

Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis, Cornell University Press, 1999.

FBI Records: The Vault – Angela Davis, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D.C., 1970–1972.

John Lennon & Yoko Ono, song “Angela,” album Some Time in New York City, Apple Records, 1972.

Rolling Stones, song “Sweet Black Angel,” album Exile on Main St., 1972.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, file “Angela Davis and the Politics of Liberation,” 2018.

University of California Archives, Angela Davis Papers collection, UC Santa Cruz, 1980–2020.

Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, Beacon Press, 2002.

bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism, South End Press, 1981.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989.

Critical Resistance, archives and publications (abolitionist manifestos and campaigns, 1997–2023).

Summary

The Face of the Struggle

Angela Davis: Black Icon, Feminist, and Committed Revolutionary

The Fire of Thought

Notes and References