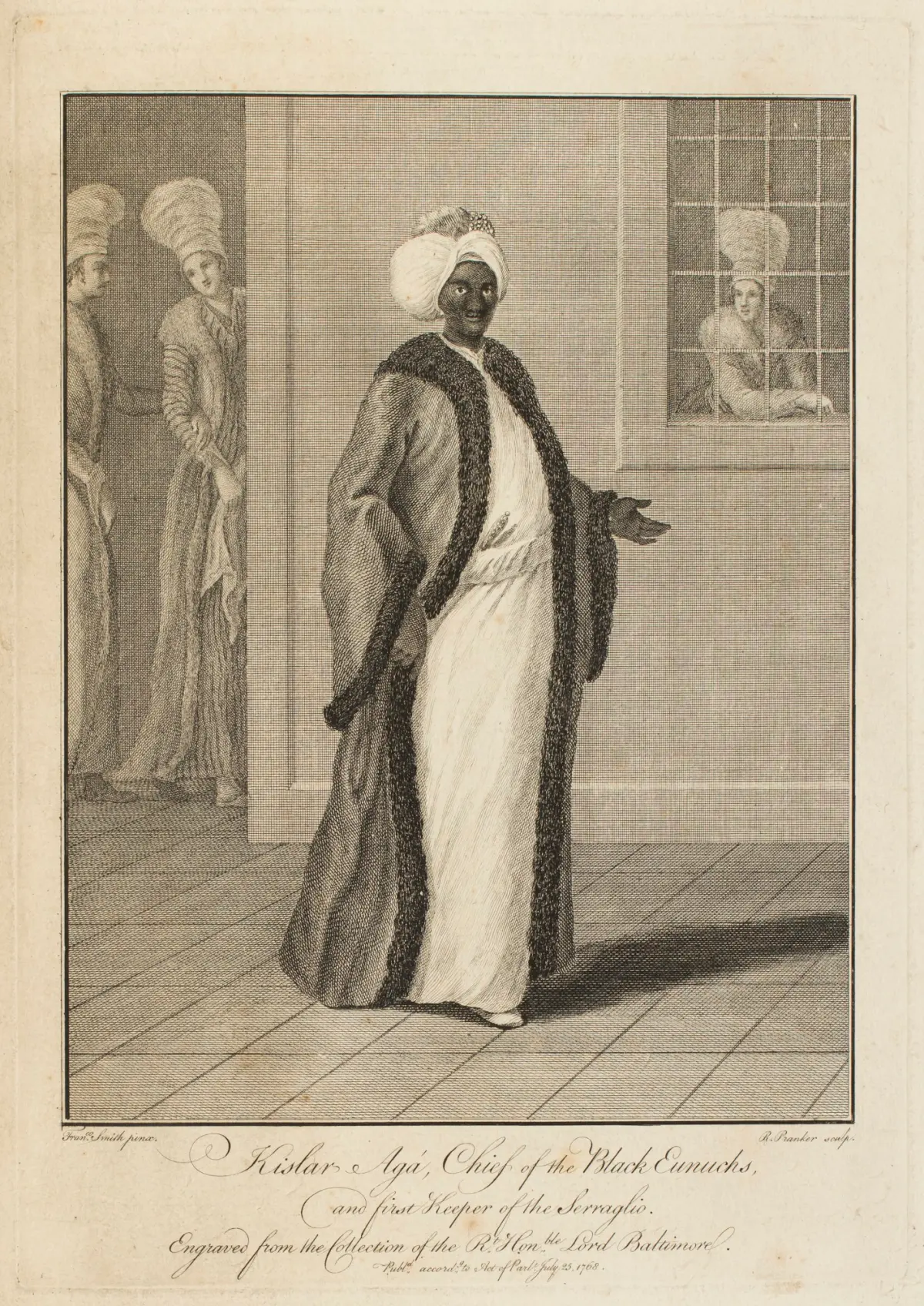

They were enslaved men, taken from East Africa, castrated, and trained to serve in the sultan’s palace. Yet these mutilated men would become masters of power. From the 16th to the 19th century, the Kızlar Ağa, Black eunuchs of the Ottoman imperial harem, governed the intimacy of the throne, controlled colossal fortunes, and shaped the politics of Istanbul from behind the scenes. Their story, between servitude, religion, and silent ascension, reveals the hidden face of an empire where the most powerful were not always the ones seen.

Kızlar Ağa or the hidden power of the ottoman harem

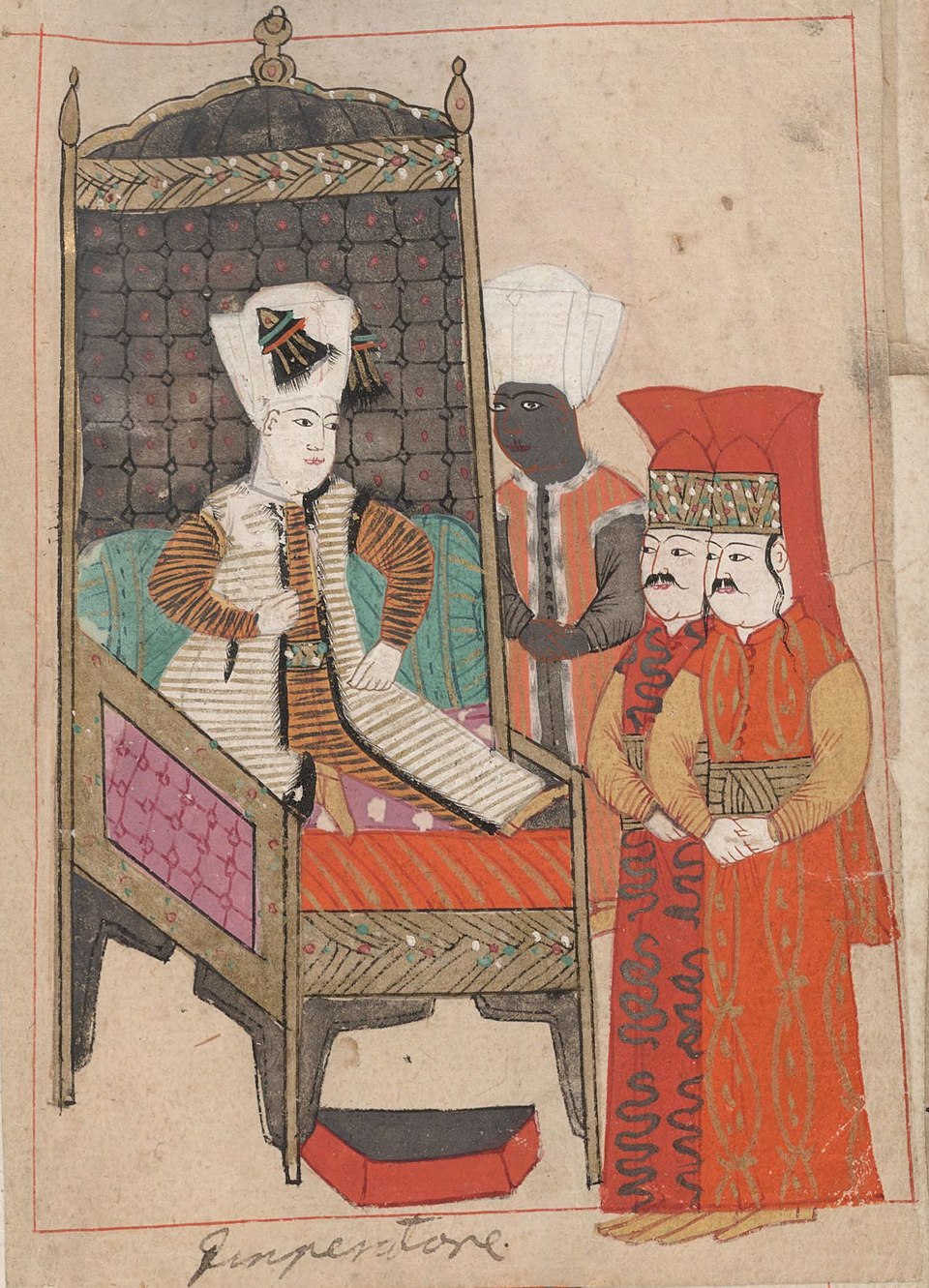

Topkapı, the beating heart of the Ottoman Empire. Beyond the golden domes and still-water gardens, behind the grilles of the harem, another authority resounded—one different from that of the sultan. It carried neither sword nor vizier’s turban, but a black cloak and the silence of mutilated men.

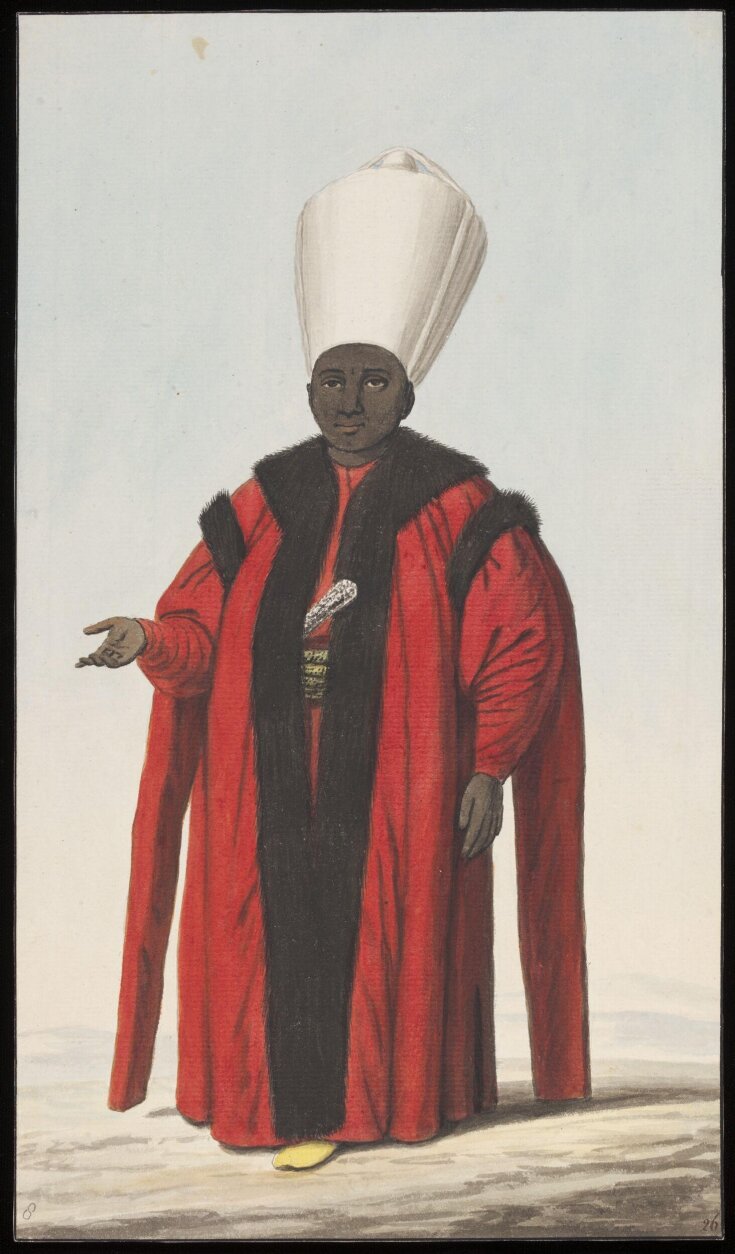

The Kızlar Ağa, literally “chief of the women,” was one of the most powerful figures in Ottoman history. A Black eunuch, an enslaved man turned dignitary, he commanded the imperial harem, oversaw the empire’s wealthiest pious endowments, and influenced successions like an invisible minister of the interior. From the 16th to the 19th century, these men without descendants were the secret architects of a power that was both intimate and political—a network of loyalties and riches extending from Istanbul to Mecca.

The title of Kızlar Ağa appears under the reign of Murad III at the end of the 16th century. This was when the harem became one of the vital centers of the state—not only a domestic space but the heart of imperial authority. Murad, fascinated by Persian splendor and Egyptian discipline, decided to entrust its guard not to white eunuchs (traditionally from the Balkans) but to Black eunuchs purchased in the markets of the Nile and the Red Sea.

The first among them, Habeshi Mehmed Ağa, inaugurated a tradition that would last more than three centuries. Under him, the role surpassed simple surveillance of the concubines and became a state institution. The Kızlar Ağa was now the third highest figure in the empire, after the grand vizier and the sheikh ul-islam.

Black eunuchs came mainly from Sudan, Nubia, or Abyssinia. Taken as children or sold, they were castrated in clandestine workshops in Egypt or Abyssinia by Coptic or Jewish hands (since Islam forbade mutilation). Those who survived the trauma—fewer than one in ten—were resold at a high price to serve in the palaces of Cairo and later Istanbul.

In Ottoman logic, a man deprived of descendants represented the ideal servant: without lineage, without hereditary ambition, and without the temptation of marriage, he embodied absolute loyalty to the sultan. At Topkapı, these young enslaved men were trained in discipline, court etiquette, and administration. The most intelligent became scribes, stewards, or keepers of the keys. At the top of this hierarchy stood the Kızlar Ağa, appointed by the sultan himself, granted a residence in the palace, and assigned a fiscal domain.

The harem he oversaw was not merely a place of pleasure but a school of power. The favorites learned arts, languages, and feminine diplomacy. The Kızlar Ağa controlled their every movement. He organized supplies, filtered visitors, transmitted messages from the valide sultana—the sovereign’s mother—and sometimes from the favorite consort. No minister, not even the grand vizier, entered without his permission. The Kızlar Ağa also held a crucial function: the education of young princes until puberty. He knew their temperaments, their ambitions, their fears. In moments of succession crisis, this intimate knowledge became a political weapon.

But the true core of his power lay elsewhere. Beginning in 1586, the sultan entrusted the Kızlar Ağa with managing the waqfs of the Haremeyn, immense pious endowments that funded Islam’s holy sites, Mecca and Medina. Revenues came from lands, inns, markets, and sometimes entire villages. Each year, the Kızlar Ağa supervised the sürre convoy, the caravan of imperial gifts to Arabia. Through this economic network, he controlled a colossal budget and enjoyed near-total autonomy.

In practice, he controlled part of the empire’s finances. Some waqfs covered territories as far as Athens or Damascus. This wealth enabled Black eunuchs to build mosques, schools, and public baths. Their names are still engraved on Istanbul’s stones, like that of Hacı Beşir Ağa, a major figure of the 18th century who built the Tophane fountain and supported the artists of the Tulip Era.

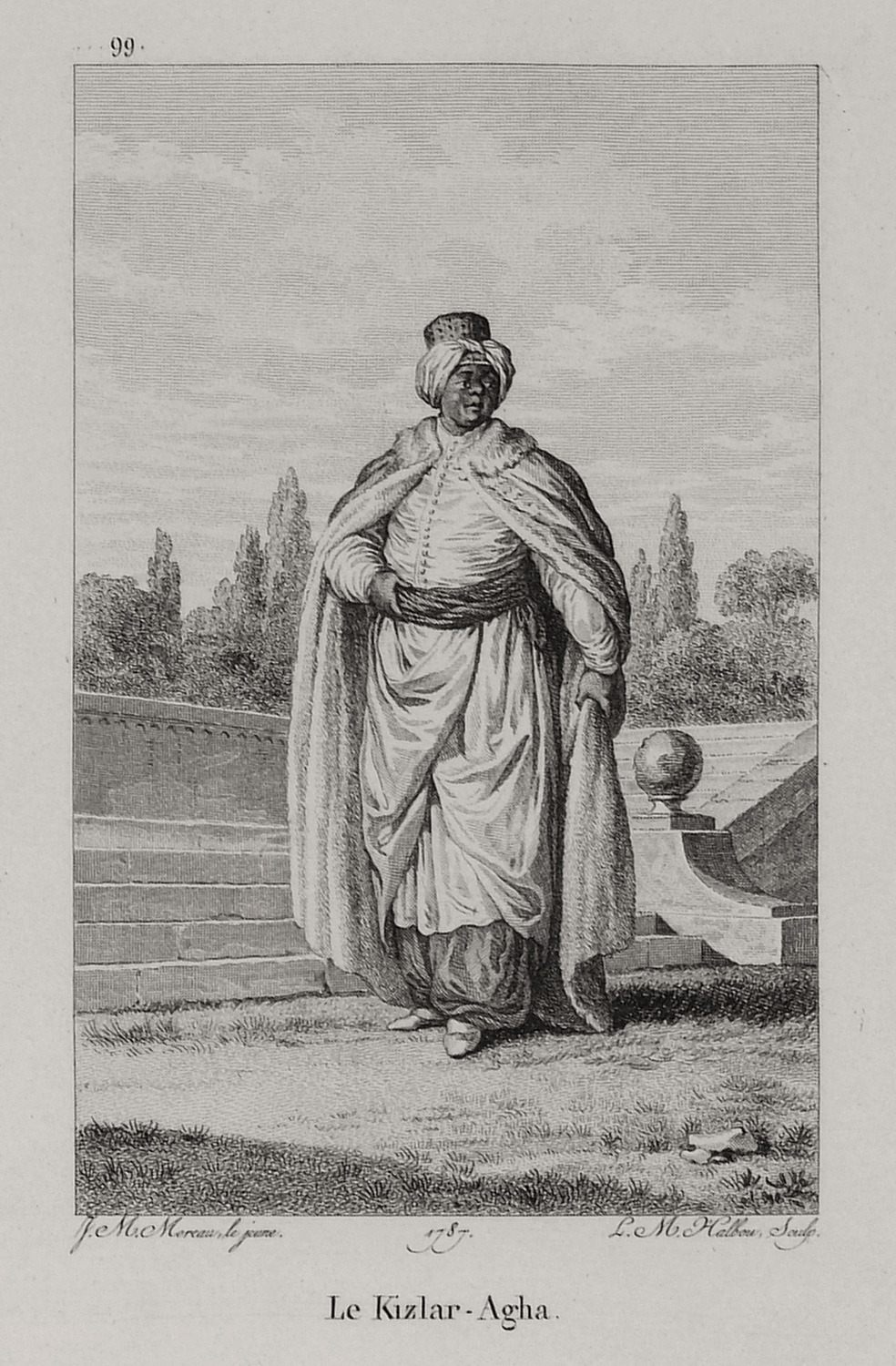

This rise provoked jealousy. The viziers viewed this parallel power with suspicion—a force born in the heart of the seraglio yet independent of the military and administrative hierarchy. Yet the sultan needed this counterweight. In an empire where corruption gnawed the administration, the eunuch-slave offered a guarantee of loyalty, for he owed everything to the palace. In return, he received a paradoxical freedom: once he left service, the Kızlar Ağa obtained a deed of liberation and a gilded exile in Egypt, where he became governor, merchant, or administrator of the waqfs he once managed. Many died wealthy, founders of mosques and charitable endowments in Cairo.

The power of the Kızlar Ağa reached its peak between the 17th and 18th centuries, during the “Sultanate of Women.” Imperial mothers (Kösem, Turhan, the valide of Mehmed IV) governed from the harem and found reliable allies in these eunuchs. In 1651, Kızlar Ağa Uzun Süleyman participated in the killing of the formidable Kösem Sultan to support Turhan’s regency. Under Hacı Beşir Ağa, the position became a true internal viceroyalty: he influenced vizier appointments, intervened in trials, and decided successions. Europe knew it well—ambassadors from Venice and France always sought the Kızlar Ağa’s favor before approaching the sultan.

But the golden age carried the seeds of its own end. The 19th century brought the reforms of Mahmud II, who sought to modernize the state and dismantle the structure of the old seraglio. In 1834, the management of the Haremeyn waqfs was taken from the Kızlar Ağa and transferred to a ministry of endowments. Black eunuchs lost their economic monopoly, then their political influence. The harem itself was reorganized and stripped of its symbolic power. On the eve of the Young Turk revolutions of 1908, the position survived only as a ceremonial relic, a shadow of a vanished world.

Yet the memory of these singular men endures. Their story condenses all the contradictions of the Ottoman Empire: an imperial power founded on servitude, a Black elite serving a white sultan, enslaved men governing free subjects. Their mutilation, far from being only a physical tragedy, was the price of unprecedented proximity to sovereignty. Their lineage-less loyalty made them guardians of the dynasty.

Their presence in the harem also illustrates the empire’s racial depth: Africa was not a periphery but a source. These eunuchs embodied the link between the Mediterranean and the Black world, between the Islam of the desert and that of imperial courts. Ottoman archives show that many still bore their African names, preceded by the title “Habeshi” or “Sudani.” In a multiracial empire, they were the only Africans to hold a central institutional role.

Their power was also a power of memory. They built mosques, funded schools, and wrote chronicles. Their waqfs remain—silent but present—in the stones of Istanbul, Cairo, and Medina. In them crystallizes the invisible face of the Ottoman state, an empire where the sultan’s household mirrored the world and where Black slaves held the keys to sovereignty.

When the last Kızlar Ağa was abolished in the early 20th century, an entire chapter of the old palatial civilization disappeared. Topkapı became a museum, the harem a setting for foreign visitors. Power had shifted to ministries and armies. But in the history of Ottoman Islam, the Kızlar Ağa remains the most fascinating figure: a man without descendants who governed the intimacy of the throne, a servant who became a lord, a voice from Africa whispering in the ears of sultans.

Notes and References

- Hathaway, Jane. Beshir Agha: Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Imperial Harem. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Junne, George H. The Black Eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire: Networks of Power in the Court of the Sultan. I.B. Tauris, 2016.

- Scholz, Piotr O. Eunuchs and Castrati: A Cultural History. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001.

- Freely, John. Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul. Penguin Books, 2000.

- Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru. Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapı Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. MIT Press, 1991.

- Tayyarzade Ahmed Ata. Tarih-i Ata. Istanbul, 1876.

- Mehmed Süreyya. Sicill-i Osmanî. Istanbul, 1890–1895.

- Hathaway, Jane. “The Role of the Chief Eunuch in Ottoman Politics and Religion.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 34, 2002, pp. 231–255.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya. Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. I.B. Tauris, 2005.

- Shaw, Stanford J. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- İnalcık, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. Phoenix Press, 1997.

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman’s Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books, 2005.

- Hoca Sadeddin Efendi. Tacü’t-Tevarih (The Crown of Chronicles).

- Hathaway, Jane. “The Politics of Households in Ottoman Egypt: The Rise of the Chief Eunuch.” Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 40, no. 4, 2004.

- British Museum Archives. “Illustrations of the Chief Black Eunuch (Kizlar Agha).” Ottoman Collection, 18th century.

- Hathaway, Jane. The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1800. Pearson Longman, 2008.

- Zilfi, Madeline C. Women and Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Design of Difference. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya & Kate Fleet (eds.). The Cambridge History of Turkey, Vol. 2: The Ottoman Empire as a World Power, 1453–1603. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Hathaway, Jane & Thomas Philipp (eds.). The Arab Lands in the Ottoman Era: Essays in Honor of Albert Hourani. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2004.

Summary

- Kızlar Ağa or the Hidden Power of the Ottoman Harem

- Notes and References