On February 23, 1802, in a narrow gorge of the Artibonite, Toussaint Louverture’s troops confronted the French army under Rochambeau. A French victory? A Haitian defeat? In reality, Ravine-à-Couleuvres illustrates the ambiguity of the colonial war: an indecisive yet decisive battle, where the tenacity of the insurgents already foreshadowed the failure of Napoleon’s expedition.

The echo of the bloodied gorges

February 1802. Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul, decided to put an end to the “anomaly” of Saint-Domingue: a wealthy colony now under the authority of a former slave turned commander-in-chief, Toussaint Louverture. To restore colonial order and reassert French sovereignty, he dispatched his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, accompanied by veterans of the Revolutionary army, including the formidable Donatien de Rochambeau.

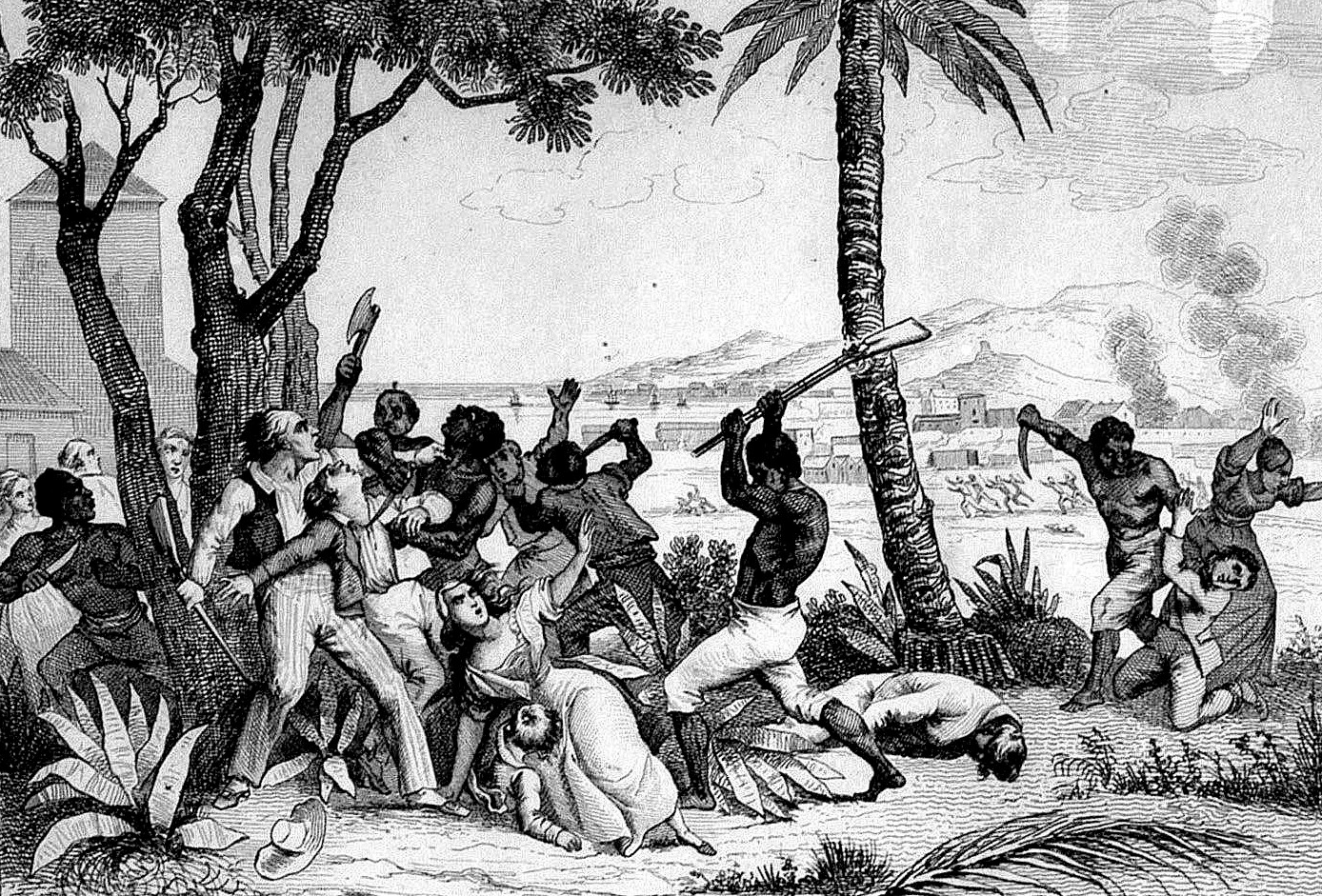

It was in this context that, on February 23, 1802, one of the fiercest and most mysterious battles of the colonial war erupted: the Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres. A narrow gorge, enclosed by wooded mountains, bristling with abatis, filled with smoke and shouts. There, French grenadiers faced Louverture’s armed soldiers and farmers. The clash was brutal, almost primitive: “a hand-to-hand combat,” Leclerc would report.

Yet beyond official accounts, a question remains: was it a French victory, a heroic Haitian resistance, or a strategic defeat for Toussaint? Numbers differ, memoirs contradict each other, and historians vacillate between glorification and skepticism.

It is this ambiguity—an indecisive but decisive battle—that we seek to explore. For Ravine-à-Couleuvres, far more than a mere military episode, illustrates both the limits of the French imperial machine and the tenacity of an army born from slavery.

To understand this foundational scene of Haitian memory, we must examine its context, actors, course, and interpretations.

An island ablaze

At the turn of the 19th century, Saint-Domingue was no longer the docile “Pearl of the Antilles” enriching France. Since the 1791 insurrection, the colony had become a permanent battlefield, where former slaves, led by Toussaint Louverture, not only defeated the colonists but also resisted the Spanish and the British. In 1801, Louverture went even further: he promulgated a constitution declaring himself governor for life of the colony.

In Paris, this challenge was unacceptable. Napoleon Bonaparte decided to strike hard. An army of over 30,000 men was sent under the command of his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc. The mission was clear: regain control, disarm Louverture, and secretly prepare the return of slavery.

Among the deployed generals, one name stood out: Donatien de Rochambeau, a ruthless veteran of the French Revolution. He would, weeks later, face Louverture in the narrow gorge of Ravine-à-Couleuvres.

The Artibonite Valley was then one of Saint-Domingue’s strategic strongholds. Fertile and densely populated, it connected the coastal plains to the mountains where insurgent troops took refuge. Controlling the Artibonite meant opening the way to Gonaïves and cutting off the black forces from their bases.

Louverture knew the terrain better than anyone. He stationed his troops there—a mix of seasoned soldiers and armed farmers—using them as scouts and auxiliary forces. For him, the Artibonite was to become a natural barrier, a trap where the French army would be worn down in the gorges, woods, and ravines.

Rochambeau, on the other hand, leading his division, advanced toward Saint-Michel-de-l’Attalaye and then toward l’Estère. His strategy was offensive: to quickly break Haitian resistance before guerrilla warfare could organize. But he would discover that this “island on fire” was a more formidable adversary than a regular army.

The armies in the field

Facing Louverture, the French army deployed relatively modest numbers. Under General Donatien de Rochambeau, assisted by Jean-Baptiste Brunet, Adjutant-General Jean-Pierre Lavalette du Verdier, and Colonel Guillaume Rey leading the 5th Light Demi-Brigade, about 2,000 men took position.

They were veterans of the Revolutionary wars, disciplined and guided by an experienced hierarchy. Their strength lay in cohesion, column maneuvers, and the use of light artillery. But the terrain was against them: Ravine-à-Couleuvres was a funnel trap where European linear tactics broke against abatis and ambush fire.

For Rochambeau’s soldiers, accustomed to the plains of Italy or the Rhine, this tropical landscape was a green prison, where every tree could conceal a rifle.

Here begins the eternal debate over numbers. According to General Leclerc’s official report, Toussaint had nearly 5,000 men: 1,500 elite grenadiers, 1,200 men chosen from the best battalions, 400 dragoons, and 2,000 armed farmers dispersed in the woods—a hybrid army mixing seasoned soldiers and improvised militias.

Yet Toussaint himself, in his memoirs written at Fort de Joux, minimized his forces: he reportedly had only 300 grenadiers and 60 cavalry. Likely a version intended to accentuate the heroism of his resistance.

Haitian historian Thomas Madiou (1847) cites 1,600 men, including farmers. Contemporary Joseph Saint-Rémy speaks of fierce resistance but inferior numbers. More recently, Sudhir Hazareesingh (2020) estimates Toussaint’s army at around 3,000 men—a compromise between exaggeration and understatement.

In any case, Louverture’s troops were an explosive mix: soldiers trained in European discipline, lightning cavalry, and peasants turned guerrillas out of necessity. They were not a regular army in the Napoleonic sense, but a polymorphic popular force, adapted to the terrain, unpredictable, and above all motivated by a cause: freedom wrested from the colonists.

The clash in the Ravine

On the eve of the confrontation, the French occupied the heights of Morne Barade. Toussaint’s troops pressed there, harassing enemy positions through the night. The fighting was chaotic, punctuated by charges and counterattacks.

At dawn, Louverture launched a bold offensive: he rallied his cavalry and struck the plains of the Périsse plantation. The French, surprised, had to retreat in disorder into the gorges of Ravine-à-Couleuvres. The colonial army was not crushed, but it fell back, pushed by adversaries who knew every fold of the terrain. Already, the Artibonite demonstrated it would be a fortress harder to subdue than expected.

At dawn on February 23, Rochambeau ordered the assault. Ravine-à-Couleuvres was a narrow gorge with steep wooded flanks. Abatis prepared by the Haitians blocked the passage. From the heights, armed farmers fired from ambush, while Louverture’s grenadiers held the entrenchments.

General Leclerc’s report, sent to Paris, summarized the intensity of the clash in one sentence:

“There was hand-to-hand combat; Toussaint’s troops fought well, but all yielded to French intrepidity.”

The reality was more complex. Fighting lasted hours in total confusion. The French advanced in waves, climbing over abatis at heavy cost. The Haitians resisted step by step, firing from the heights and counterattacking in squads. It was not a conventional battle: it was visceral, a gorge war, where European discipline clashed with the fury of men defending their freedom.

Eventually, under pressure, Toussaint’s lines gave way. His troops retreated toward Petite-Rivière-de-l’Artibonite, leaving the field to the French. But Rochambeau, exhausted, lacked the means to exploit this breakthrough.

Casualties remain uncertain:

- Leclerc mentions 800 Haitian dead against 200 French losses and 30 prisoners.

- Thomas Madiou nearly reverses the figures: 300 losses for Toussaint’s men, 200 for Rochambeau.

- Hazareesingh and Madison Smartt Bell stress the ambiguity: a French tactical victory, costly and sterile.

The battle, like much of this war, was indecisive: the French advanced but at the cost of their strength, while Toussaint, though defeated, preserved his forces intact for the future.

Readings and interpretations

In his report to the Minister of the Navy, General Leclerc chose a terse formula:

“Toussaint’s troops fought well, but all yielded to French intrepidity.”

This account, intended for Paris, served a political purpose: to reassure the First Consul and the French public, showing that the expedition progressed and that the Republic’s soldiers remained invincible even in tropical gorges.

In reality, this version reduces a complex confrontation to a moral victory. French losses are minimized, and Haitian resistance relegated to mere bravado. It is less a military report than an exercise in imperial propaganda.

On the Haitian side, memoirs and historians present a very different picture.

- Toussaint Louverture, in his memoirs at Fort de Joux, emphasized the disparity in forces and his men’s courage, reducing his numbers to a few hundred to highlight their heroism.

- Thomas Madiou (1847), father of Haitian historiography, claimed Toussaint commanded around 1,600 men, including farmers, with roughly balanced losses: about 300 Haitian dead versus 200 French.

- Joseph Saint-Rémy (1850) and Victor Schœlcher (1889) stressed the epic character of the resistance, highlighting the perseverance of a popular army facing an organized colonial power.

Here, the battle is seen as a moral victory: even in retreat, Toussaint proved his troops could stand up to the Empire’s best soldiers.

Modern historians, more critical, underline the fight’s ambiguity.

- Madison Smartt Bell (2007) describes a “confused, costly battle with no clear victor,” where the French tactical advantage was countered by attrition and guerrilla warfare.

- Sudhir Hazareesingh (2020) estimates Toussaint’s army at around 3,000 men, concluding a French tactical victory but a strategic stalemate: Rochambeau could not exploit his success, and his troops remained isolated.

Ultimately, Ravine-à-Couleuvres captures the essence of Saint-Domingue’s war: every French victory resembled a Pyrrhic win, and every Haitian defeat became a symbol of resistance.

An “Indecisive” but decisive battle

On paper, the Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres looks like a French victory. Toussaint’s troops retreat, and the colonial army holds the field. Yet this success is fragile. The French lose men, time, and crucially, communication with General Jacques Maurepas’ regiment isolated in the mountains.

Strategically, Rochambeau gains only limited territory. The Artibonite Valley is not pacified. The French expedition bogs down in a war of attrition that drains its forces far more than it strengthens them.

For Toussaint’s troops, the retreat to Petite-Rivière-de-l’Artibonite is not a rout but a calculated maneuver. Louverture preserves his army intact, ready to fortify Crête-à-Pierrot, a high point of resistance that would mark Haitian imagination weeks later.

Thus, Ravine-à-Couleuvres becomes a heroic prelude: even while yielding ground, the insurgents proved they would not be crushed. Guerrilla tactics, attrition, and constant harassment became the main weapons of an army that could not match French discipline but dominated over time.

In Haitian historiography and collective memory, the battle is not seen as a defeat but as proof of courage. It fits into a sequence where each fight, even tactically lost, contributed to wearing down the enemy and advancing inexorably toward Vertières (1803) and independence.

Ravine-à-Couleuvres embodies this paradoxical truth: the French won battles, but lost the war.

Memory and legacy

On the French side, Ravine-à-Couleuvres is often relegated to a mere “episode” of the Saint-Domingue expedition. Official accounts, like Leclerc’s, stress the grenadiers’ bravery but gloss over losses and strategic deadlock. French military tradition preferred to remember troop glory rather than colonial impasse.

In 19th-century metropolitan history books, Ravine-à-Couleuvres barely appears, overshadowed by more “glorious” campaigns in Europe.

Haitian historians, however—starting with Thomas Madiou (1847) and Joseph Saint-Rémy (1850)—made Ravine-à-Couleuvres a landmark of the national narrative. It is described as a heroic battle where armed peasants, supported by a few hundred grenadiers, stood up to Napoleon’s elite.

This memory forms a chain from Bois-Caïman to Vertières: a sequence of resistances that shaped the Haitian nation. Ravine-à-Couleuvres holds the place of a moral symbol, showing that even a setback can become a victory of dignity.

Contemporary scholarship, Haitian (Jean Casimir, Claude Moïse) or foreign (Madison Smartt Bell, Sudhir Hazareesingh), invites moving beyond national myths and propaganda reports. The battle was neither a major French victory nor a crushing Haitian defeat: it was an indecisive fight revealing the strengths and weaknesses of both sides.

Thus it becomes a key interpretive lens: the French had discipline and firepower but lacked endurance and local support; the Haitians lost battles but won a war by exploiting time, terrain, and their fierce will to be free.

Ravine-à-Couleuvres: a tactical defeat, a historical victory

Ravine-à-Couleuvres lacks the mythic resonance of Vertières or the tragic aura of Crête-à-Pierrot, but it perfectly illustrates the paradoxical logic of Saint-Domingue’s war. Militarily, the February 23, 1802, clash was a French tactical victory: Rochambeau repelled Toussaint’s troops and held the ground. But historically, it was a sterile, costly, and ultimately futile victory.

Behind the numbers and reports, one fact stands out: each such battle drained the French army, weakened by losses, disease, and hostile terrain, while the Haitian army, even in retreat, regenerated among the population, in memory, and in the cause of freedom.

Ravine-à-Couleuvres was therefore a tactical defeat for Louverture but a moral victory for Haiti. It demonstrated that the indigenous army could face Europe’s finest infantry, retreat without yielding, bend without breaking.

In this way, this minor strategic battle became a major landmark of national memory: a reminder that freedom is measured not in kilometers gained or lost but in the will to resist.

In the narrow gorges of the Artibonite, the echo of gunfire and war cries still resonates as a warning to the Empire: in Saint-Domingue, military victory never guaranteed political domination.

Notes and references

- Leclerc, Charles – Reports to the Minister of the Navy on the Saint-Domingue Campaign (1802), French National Archives.

- Louverture, Toussaint – Memoirs from Fort de Joux (1802–1803).

- Madiou, Thomas – History of Haiti, Vol. II, Port-au-Prince, 1847.

- Saint-Rémy, Joseph – Memoirs of Toussaint Louverture, Paris, 1850.

- Schœlcher, Victor – Life of Toussaint Louverture, Paris, 1889.

- Hazareesingh, Sudhir – Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020.

- Bell, Madison Smartt – Toussaint Louverture: A Biography, Pantheon Books, 2007.

- James, C.L.R. – The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage, 1963.

- Casimir, Jean – The Oppressed Culture, Port-au-Prince, 2001.

- Moïse, Claude – Constitution and Power Struggle in Haiti (1801–1806), Port-au-Prince, 1990.

Summary

- The Echo of the Bloodied Gorges

- An Island Ablaze

- The Armies in the Field

- The Clash in the Ravine

- Readings and Interpretations

- An “Indecisive” but Decisive Battle

- Memory and Legacy

- Ravine-à-Couleuvres: A Tactical Defeat, a Historical Victory

- Notes and References