Tippu Tip, a 19th-century Black trader, was one of the greatest slave merchants in African history. His path—marked by a commercial empire, colonial complicity, and a forgotten war—reveals the gray areas of our Black memory. This is the story of a man who sold Africa—and sold himself.

The merchant and his ghosts

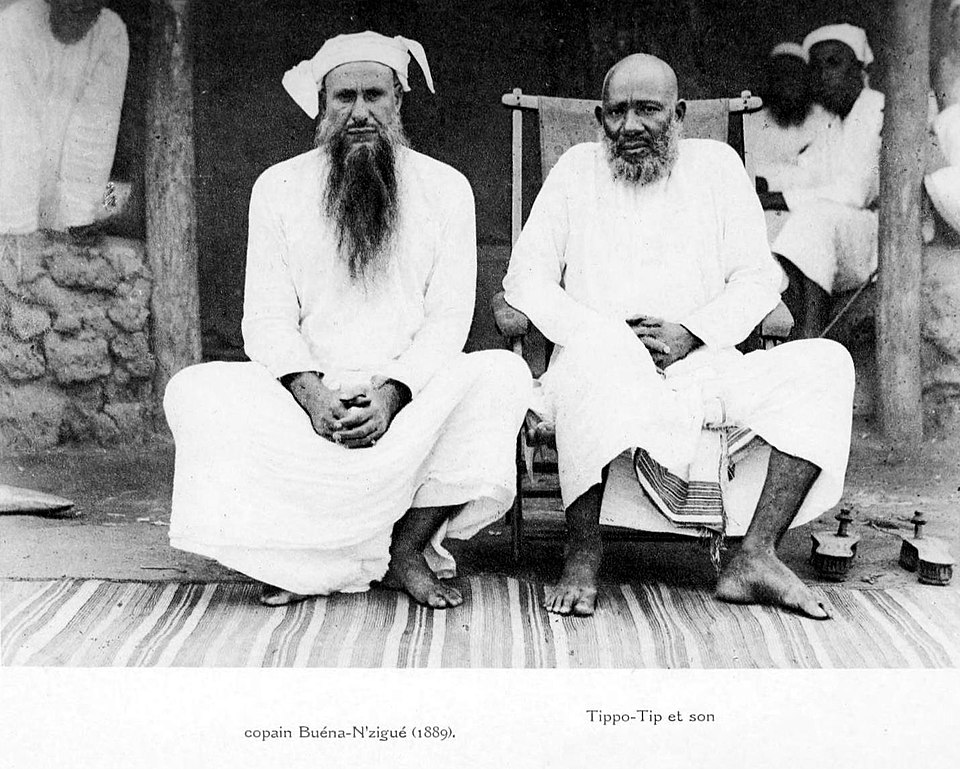

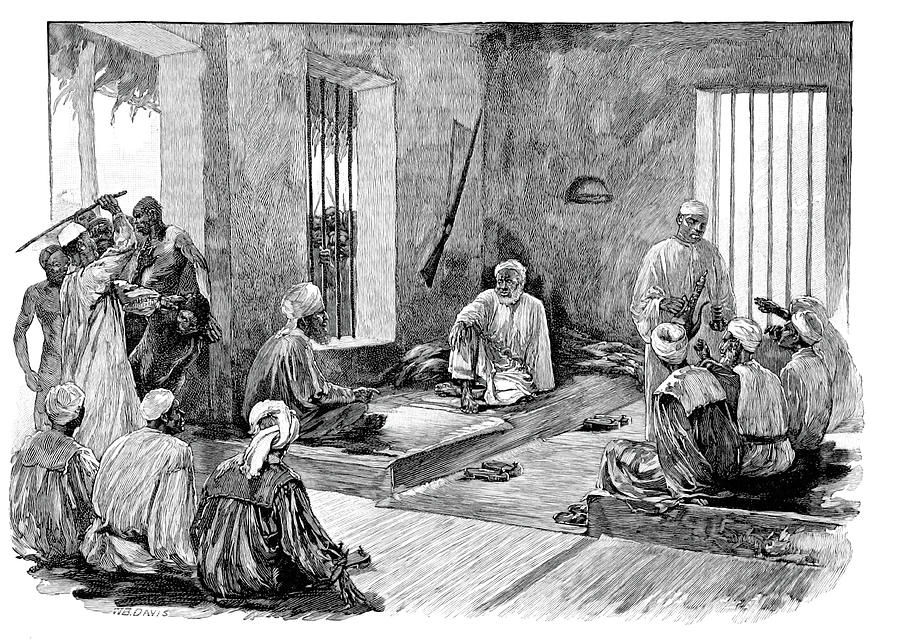

Ivory and slave trader in Africa. Photograph from 1889.

Stone Town, Zanzibar. June 1905.

In a grand white coral house, just steps from the Indian Ocean, an old man breathes his last. No crowds, no mourners. Only a few silent servants, dust-covered walls, and on a wobbly shelf, a stack of notebooks: the story of his life, written in stiff Swahili. His name was Hamad bin Muhammad al-Murjebi. But history remembers him by another name: Tippu Tip—the man who made gold rain on caravans and fire rain on villages.

His name still echoes in the winding paths of the Congo River, on ivory routes and human flesh trails. He was at once explorer, trafficker, governor, strategist—and executioner. Sometimes, even a traitor to his own memory. Black-skinned, yet head of a slave empire. Arab by name, but rooted in Bantu lands. A scholar, yet brutal. A visionary, yet blind to the ruins he sowed.

In European accounts, he was a “useful ally,” a “great merchant.” In African memory, he defies easy categorization. Tippu Tip is what history dislikes: a gray figure, as disturbing as he is fascinating. A knot in the grand tapestry of the slave trade, one neither the West nor Africa can untangle without pain.

At Nofi, we believe such figures must be told—not to celebrate them, but to better understand the deep mechanics of oppression, even when they wear a Black face. For silence is also complicity. And tormentors can come from among us, too.

Zanzibar, crucible of contradictions (1830–1850)

Part of the Michael Graham-Stewart Collection on Slavery.

Another uncatalogued photograph, mounted on the reverse,

“Tullbagh – Cascade on Waterfall River.”

19th-century Zanzibar was not just a port. It was a gateway—one that opened onto the Indian Ocean and the African interior. The air reeked of cloves, blood, and damp wood. Dhows filled with men and goods docked without cease. In the limewashed palaces of Omani rulers, the slave trade was not hidden—it was the backbone of the economy.

It was here, around 1837, that Tippu Tip was born, in a house of stone and secrets. He was the product of a world defined by intersecting lines: his mother Arab, his father Swahili, his grandmother Bantu. He was African, Arab-Muslim, insular and continental—a mirror of vertical miscegenation, uniting the high (merchants) and the low (captives) without ever confusing them.

In this stratified society, skin color alone did not define status. Islam played its role. So did money. But true power here was the right to capture others.

The so-called “Arab-Muslim” trade—often downplayed out of modesty or denial—was anything but folkloric. It was structured, violent, industrial. And in this machine, Tippu Tip hardened. He listened to his father’s tales, a seasoned caravaner who crossed the interior seeking ivory—and men.

Before twenty, he was leading his own expeditions. At the head of a hundred armed men, he entered the heart of the continent not as a conqueror, but as a shadow broker—mediating between Europe’s hunger for objects and the Black flesh that would foot the bill.

But how do we speak of a Black man who captured other Black men? How do we explain that Africa sometimes sold Africa—without reducing it to mere betrayal or excusing the unspeakable?

Zanzibar doesn’t hold all the answers. But it lays bare the foundations: a merchant society, hierarchical, globally connected, where Africans could be both buyers and products, traders and victims.

Tippu Tip was no historical accident. He was its perfect symptom.

The empire of chains: Building his wealth (1850–1870)

This was the era when Tippu Tip became more than a caravan leader—he became a mobile empire.

At the head of dozens, then hundreds of armed men, he no longer merely followed commercial routes opened by his elders. He extended them. Transformed them. Bled them dry. Every river crossing, every burned village, every shackled captive was an act of power—not state power, but one enforced by fear and efficiency.

Tippu Tip’s caravans were mobile fortresses. They advanced with flintlock rifles, supplies, porters, guides, and chains. Men were captured or bought—often both: bought with weapons, or seized in merciless raids. Women were often reduced to sexual objects, wives on the road, domestic slaves, or currency.

In this economy of horror, ivory was white gold. Massive elephant tusks, precious and coveted, made their way to Zanzibar, then to Bombay, London, Paris. They adorned European pianos while African children walked barefoot behind the caravans.

At every stop, Tippu Tip built a post: Kasongo, Nyangwe, Riba Riba… These trading outposts became merchant cities where Swahili, Arabic, Lingala, French—and the cries of captives—mingled. He installed garrisons, levied taxes, appointed delegates. It wasn’t yet a state, but it was already territorial domination. The heart of Africa, even before the Belgians, was carved up by a Black man with an Arab name.

And here lies the complexity: can we call it “collaboration” when Black expansion aligns with colonial logic? Can it be sovereignty when built on chains? Or did Tippu Tip, a pragmatic merchant, simply play by the rules of a world already rotten?

We must also listen to those who weren’t allowed to write: the resisters, the runaways, the burned villages, the displaced peoples, the broken lineages. For if Tippu Tip enriched Zanzibar, he bled the Congo dry.

There is a truth in that silence—one harsher than any archive: the wealth of a few was built on the devastation of many. And that “few” sometimes bore our skin.

The man who met Livingstone (1870–1880)

In European accounts, Tippu Tip now takes on a nearly romantic air. A Black explorer, multilingual, able to negotiate with Western powers while leading armies of caravaners. An “ally” of civilization, they say. But read between the lines: Europeans admired him as much as they feared him.

It was then that he met David Livingstone, the famed British missionary and explorer. The contrast was stark: a white man come to “abolish the slave trade” in God’s name, and a Black man living off it. Yet they shared the road, meals, nights under canvas. Tippu Tip sometimes even helped Livingstone through hostile areas, supplying him with food and porters.

A perfect ambiguity. For what Livingstone didn’t say (or chose to ignore) was that without “Arabs” like Tippu Tip, no European survived the African interior.

In these then-uncharted regions, Tippu Tip was an uncrowned king, warlord, diplomat, merchant. Western powers negotiated with him, recognized his authority—until they could replace him.

But what did he think of these Europeans? Some accounts suggest he mistrusted their greed, understood early on that their presence foretold vast dispossession. Others claim he saw them as a way to legitimize his power against Arab and African rivals. Between diplomacy and duplicity, Tippu Tip played all sides.

But could he really not have seen what was coming? That these men with crosses and maps would redraw borders in blood? Or did he, like so many others, believe his local power would survive the Empire’s march?

One thing is certain: by dealing with Livingstone, Stanley, and Leopold II, Tippu Tip became an active link in the colonial project—not just a pawn. He opened the gates of the continent to those who would chain it.

Governor of darkness (1880–1890)

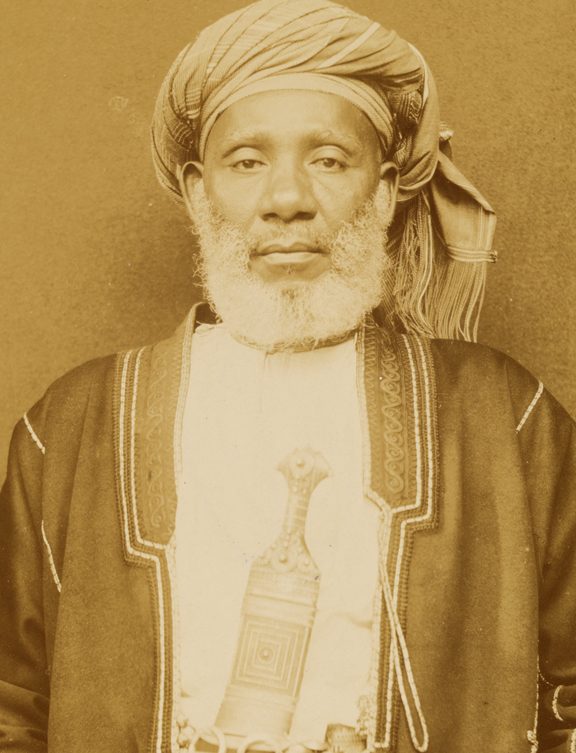

Tippu Tip (1832 – June 14, 1905), born Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi, was a Swahili-Zanzibari slave trader, ivory merchant, explorer, plantation owner, and governor of Stanley Falls. He served a succession of sultans of Zanzibar. Tippu Tip traded slaves for the clove plantations of Zanzibar. As part of the vast and profitable ivory trade, he led numerous commercial expeditions into Central Africa, establishing lucrative trading posts deep within the region. He purchased ivory from local suppliers and resold it for profit in coastal ports.

Image from page 185 of Five Years with the Congo Cannibals by Herbert Ward, 1890.

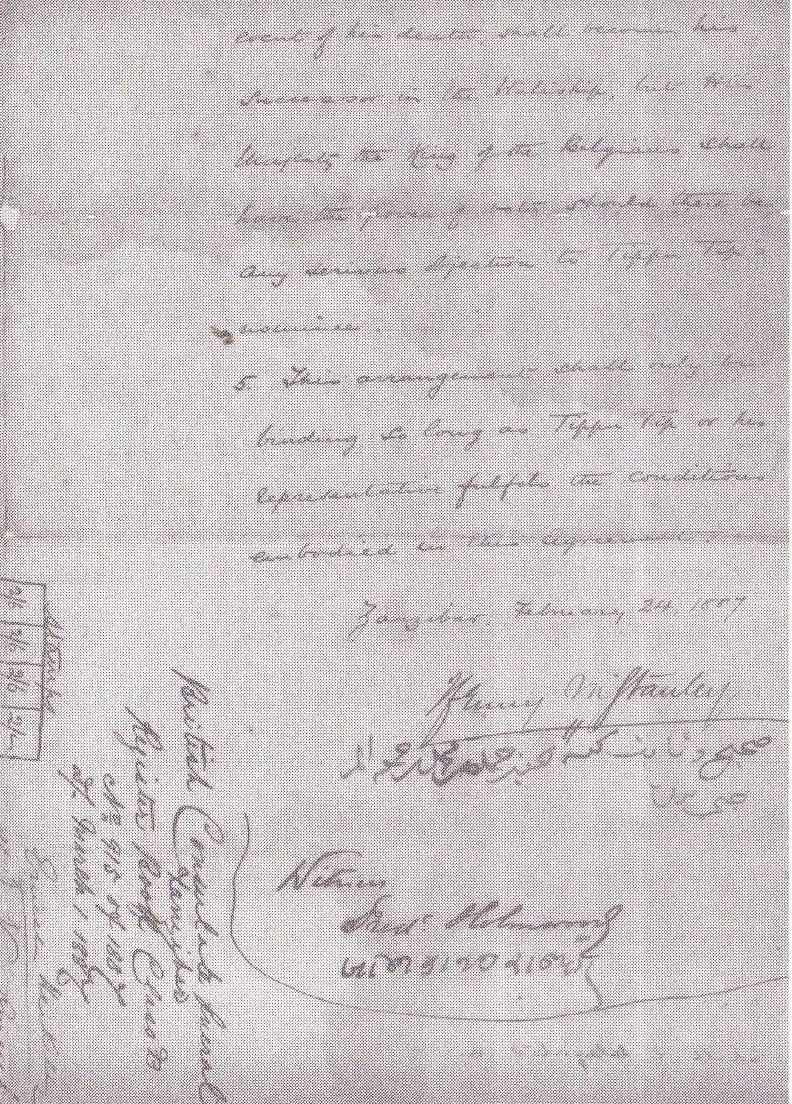

1887. Zanzibar.

The world shifts. A contract is signed between two men: Tippu Tip and Henry Morton Stanley, emissary of King Leopold II of Belgium. The objective? To name Tippu Tip governor of the Stanley Falls District, in what would become the Congo Free State—a euphemism for hell on earth.

Tippu Tip, once a free man, becomes a governor in the name of a European monarch. He is granted a seal, an official title, and authority over a territory as vast as Germany. A Black man serving a white king. An unnatural alliance? Or the final trick of a lucid merchant sensing the end of his dominion?

In this territory, the trade continues—but now with state approval. Tippu Tip levies taxes, raises troops, regulates ivory routes… all while navigating an increasingly oppressive colonial presence. The ambiguity of his role reaches its peak: collaborator? intermediary? puppet governor?

His son, Sefu bin Hamid, takes over in the field. But tensions soon erupt. The Belgians want no more power-sharing. They want total control. War breaks out: the Arab-Congo War (1892–1894). Sefu is killed. Tippu Tip’s outposts are destroyed. His allies flee or surrender. His empire collapses.

And here, a naked truth emerges: what Europeans give, they always take back. Tippu Tip thought he was negotiating his survival. He served as a transitional tool—an African mask for a European plan.

He returns to Zanzibar, worn out, defeated, aware that history’s winds have changed. The Congo will never again be in African hands. It will be subjugated, looted, dismantled—with a Black man in a white turban at the start of the chain.

Perhaps this is the ultimate tragedy: trying to play with the powerful, without realizing that one does not play with Empire. Empire plays with you.

The merchant of memory (1890–1905)

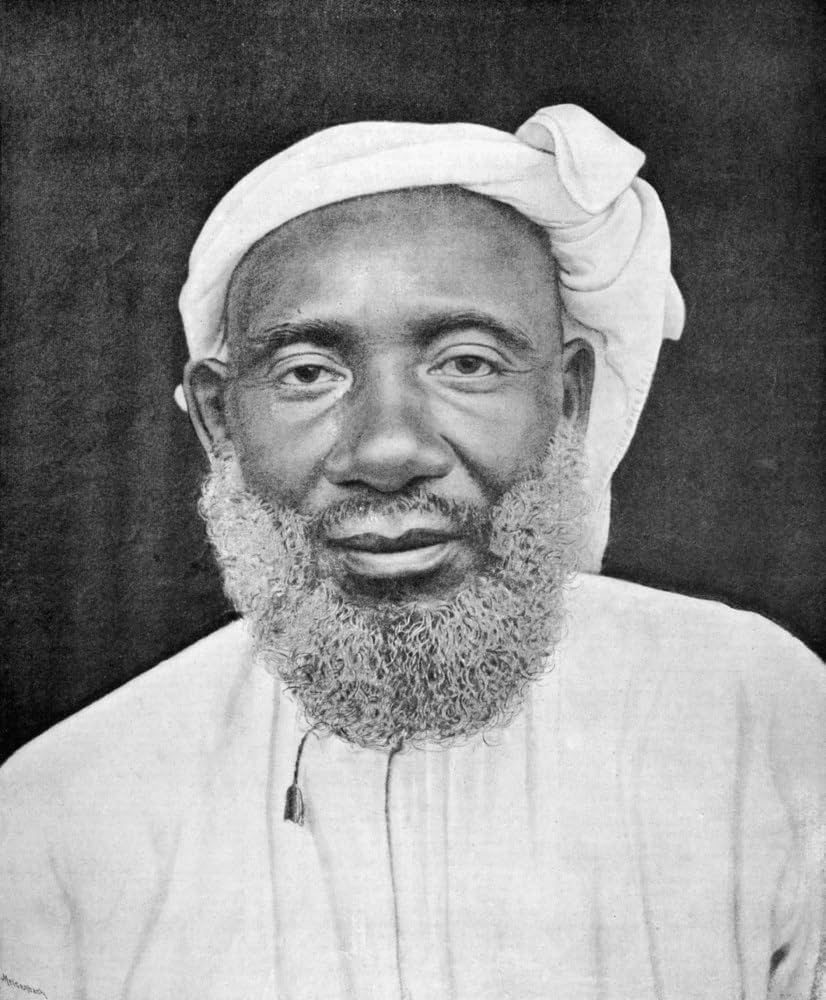

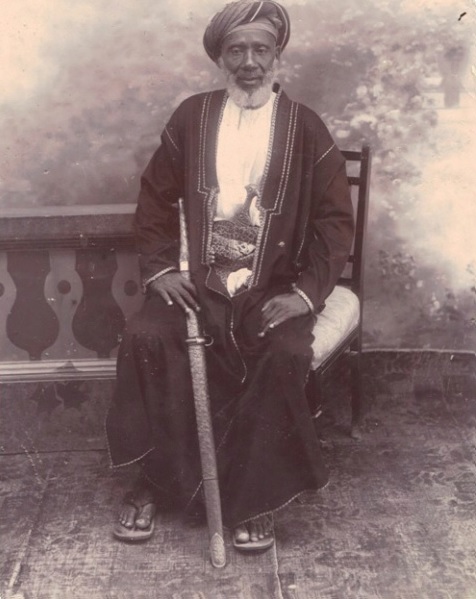

Silver gelatin photograph of Mohammad bin Hamed, also known as Tippu Tip (circa 1830–1905). Born in Zanzibar, he embarked on the lucrative caravan trade across Central and East Africa. During the 1870s and 1880s, Tippu Tip was the most powerful figure in what is now eastern Zaire, commanding some 50,000 firearms. He amassed enormous wealth through the slave trade and the ivory trade, serving clients such as the Sultan of Zanzibar—whom he remained fiercely loyal to—and Henry Morton Stanley. Despite his efforts, he was unable to maintain control around Lake Tanganyika in the face of the European partition and conquest of the region. In the late 1880s, he was briefly appointed governor of Stanley Falls by King Leopold II of Belgium (1835–1909), whose imperial and commercial ventures would come to dominate the Congo Basin. Tippu Tip eventually retired to Zanzibar and wrote his autobiography, which has become a classic of Swahili literature.

Old, ill, yet still influential, Tippu Tip retires to his home in Stone Town, at the heart of Zanzibar. There, among coral walls and carved balconies, he undertakes what few men of his world ever dared: he writes.

His autobiography, dictated in Swahili, is one of the first accounts by an African about the interior of Africa before full colonization. He recounts his caravans, alliances, expeditions, and dealings with Europeans. He offers his version of history. But the narrative is selective: not a word about the pain inflicted, not a line for the captives, no moral introspection.

There’s something chilling in this calm stance—as if the slave trade were merely business, a necessary step in the world’s ledger. Tippu Tip doesn’t present himself as a tormentor. He sees himself as a businessman, a trader in an era where violence was the norm. His writing is thus a bid for redemption through the pen—but without confession.

And yet, it remains. The text exists. And it forces us to confront our discomfort. Because this is not a European speaking of Africa. This is an African speaking of himself—without detour, without apology. He becomes, despite himself, a crucial witness to that troubled time: the end of an old world and the dawn of the colonial one.

Tippu Tip dies in 1905, the same year Belgium officially takes possession of the Congo, and voices like Casement’s and Morel’s denounce the horrors of the Free State. He dies as colonial history begins to be written without Africans.

But his silence on the victims, his refusal to accept responsibility, are empty lines we must now fill. For writing history is not enough. One must also ask: who is speaking? And for whom?

Decolonizing the narrative around Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip appears in no school textbook. His name resonates neither as hero nor as executioner. It floats in a gray zone. Too African to be blamed by Europe. Too complicit to be celebrated by Africa.

And yet, we must speak of him. Not to build him a statue. But to deconstruct a larger myth: that of an Africa only ever victimized.

Because history is more complex. Yes, Africa was shattered, devastated, exploited by brutal colonial powers. But Black hands sometimes held the chains. African figures—sometimes brilliant ones—served imperial logics: out of ambition, opportunism, fear, or pride.

To decolonize the narrative is not to rewrite history so it flatters us. It is to give it back its depth, its humanity, its contradictions. Tippu Tip forces us to ask the right questions:

- Can one be African and an oppressor?

- Can we denounce the Atlantic slave trade while ignoring the eastern trades?

- Can there be forgiveness without understanding?

Today, Tippu Tip’s name is still honored by some in Zanzibar as a builder, a brilliant trader, a visionary. Others denounce him as one of the greatest traffickers of human flesh in his time. Both are right. And therein lies our duty of memory: to reject shortcuts. To face the shadows. To name things.

Because only by facing our ghosts can we write a new story.

Ours.

Complete.

Dignified.

Human.

Sources

- Tippu Tip, Maisha ya Hamed bin Mohammed el Murjebi yaani Tippu Tip kwa maneno yake mwenyewe (1905)

- Heinrich Brode, Tippoo Tib: The Story of His Career in Zanzibar & Central Africa (1907)

- Stanley, H.M., Through the Dark Continent (1878)

- Abdul Sheriff, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar (1987)

- Robert B. Edgerton, The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo (2002)

- Norman R. Bennett, Arab vs. European: Diplomacy and War in East Central Africa (1986)

- Zeinab Badawi, An African History of Africa (2024)

Summary

- The Merchant and His Ghosts

- Zanzibar, Crucible of Contradictions (1830–1850)

- The Empire of Chains: Building His Wealth (1850–1870)

- The Man Who Met Livingstone (1870–1880)

- Governor of Darkness (1880–1890)

- The Merchant of Memory (1890–1905)

- Decolonizing the Narrative Around Tippu Tip

- Sources