Ahmet Ali Çelikten, an Ottoman officer who became a colonel in the Turkish Air Force, was the first Black pilot in history. Yet his name has remained in the shadows. Neither an imperial hero nor a republican icon, this Afro-Turkish pioneer embodies a buried memory, caught between two official narratives—one of aerial modernity, the other of national identity. His journey, eclipsed from history books, forces us to rethink the place of Black figures outside the Western colonial prism.

The global history of aviation readily celebrates its pioneers. The Wright brothers, Roland Garros, Guynemer—and, for Afro-American memory, Eugene Bullard. Yet one name remains absent from official records, despite a career that places him both chronologically and symbolically among the very first Black military pilots in human history: Ahmet Ali Çelikten, known as “the Black Eagle of Izmir.”

Born in 1883 in the Ottoman Empire, of Nigerian-African descent through his mother, and trained in the imperial navy before becoming a pilot in 1914, Ahmet Ali predates all other frequently cited Afro-descendants described as “firsts” in the field. Unlike his American, Caribbean, or French counterparts, however, he did not emerge from a colonial context. He represents a different form of modernity—one from a non-Western, multiethnic empire where Afro-descendants occupied a complex space: neither wholly marginal, nor fully visible.

Forgotten by textbooks and aviation museums alike, Ahmet Ali Çelikten is a figure of the in-between: a high-ranking officer, a discreet hero of the Turkish War of Independence, and a symbol of the Ottoman Black diaspora—one to which no official space of remembrance has ever been granted.

This article seeks to restore the place of this airman whose destiny spanned world wars, imperial collapses, and racial divides—revealing a long-overlooked truth: the history of Black people is not confined to the colonial periphery. It too has flown, fought, and triumphed from the heart of other world powers.

The origins of an extraordinary pilot

Ahmet Ali Çelikten was born in 1883 in Izmir, in the Aydın vilayet—one of the oldest open ports in the Eastern Mediterranean. Cosmopolitan and multilingual, mixing Greek, Turkish, Armenian, Levantine, and African populations, Izmir was an Ottoman “interface” between Africa, Asia, and Europe. It was in this imperial melting pot that the man later recognized as the first Black military pilot came of age.

His lineage reveals a broader trajectory than that of a single individual. His mother, Emine Hanım, was of Nigerian origin, descending from enslaved or freed people who had passed through Ottoman Egypt and Crete before settling in Anatolia. His father, Ali Bey, also of African descent, belonged to the Ottoman artisan or military elite. Thus, Ahmet Ali represented the African diaspora within the empire—often made invisible, yet very much present: the Zenci Osmanlılar, or “Black Ottomans,” who lived in the major coastal cities.

Unlike European colonial societies, the Ottoman Empire did not base its political system on rigid racial hierarchy. There was no legal “color code.” That doesn’t mean discrimination was absent—but within this framework, Afro-Ottomans could access certain roles (military, technical trades, religious functions) if they demonstrated loyalty and cultural assimilation. This is the niche into which Ahmet Ali’s destiny fit.

Raised in a society where Islam played a more integrative than exclusive role, he benefited from structured education. From a young age, he showed an interest in the sea and mechanics. In an aging empire increasingly aware of its fragility against European powers, technical military schools offered a path for social advancement—and a way to serve without denying his racial identity.

His family enrolled him in the Haddehâne Mektebi, the Ottoman Navy’s technical school. There, he became one of the few African-descendant students—though not the only one. This institution, like others in Istanbul and Smyrna, trained a diverse imperial youth whose origins reflected the vast range of Ottoman territories. It wasn’t Republican France that opened doors to this young Black man—it was the late, still-standing Sublime Ottoman Porte.

This context is essential to understanding the man he would become. Ahmet Ali did not consider himself a colonized subject. He was neither dominated nor exiled. He was an officer-in-training in a state that—despite its inner tensions—recognized him as one of its own. This complex imperial status set him apart from the Afro-descendant aviation pioneers in Western countries, who had to fight segregation to fly. He operated from a gray zone of limited but real inclusion.

Ahmet Ali was, from the beginning, shaped by another narrative: that of an Islamic, bureaucratic, polyethnic empire, where Black people were never the majority, but never entirely erased. This distinction changed everything.

Ahmet Ali Çelikten’s life took a decisive turn in 1904 when he joined the prestigious Haddehâne Mektebi. During a phase of military modernization, the Empire placed its hopes in a technically skilled youth capable of facing Europe’s technological edge. As a young Afro-descendant in a corps dominated by Turkish and Arabized elites, Ahmet Ali distinguished himself through technical skill and discipline.

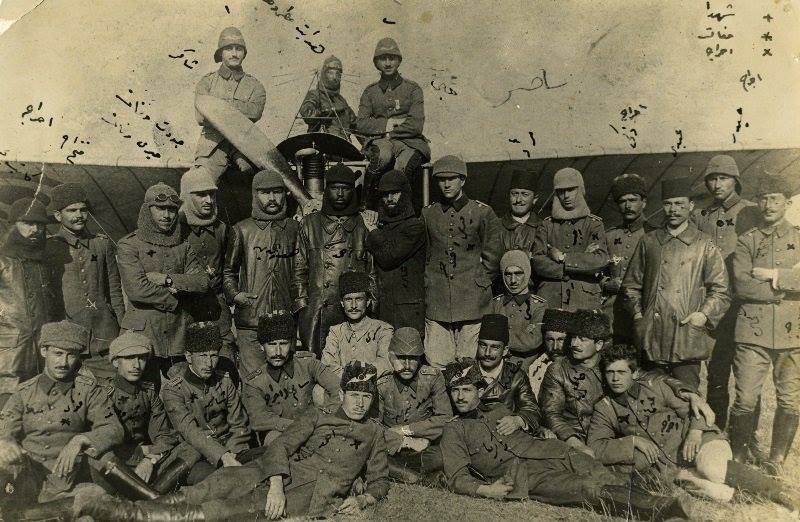

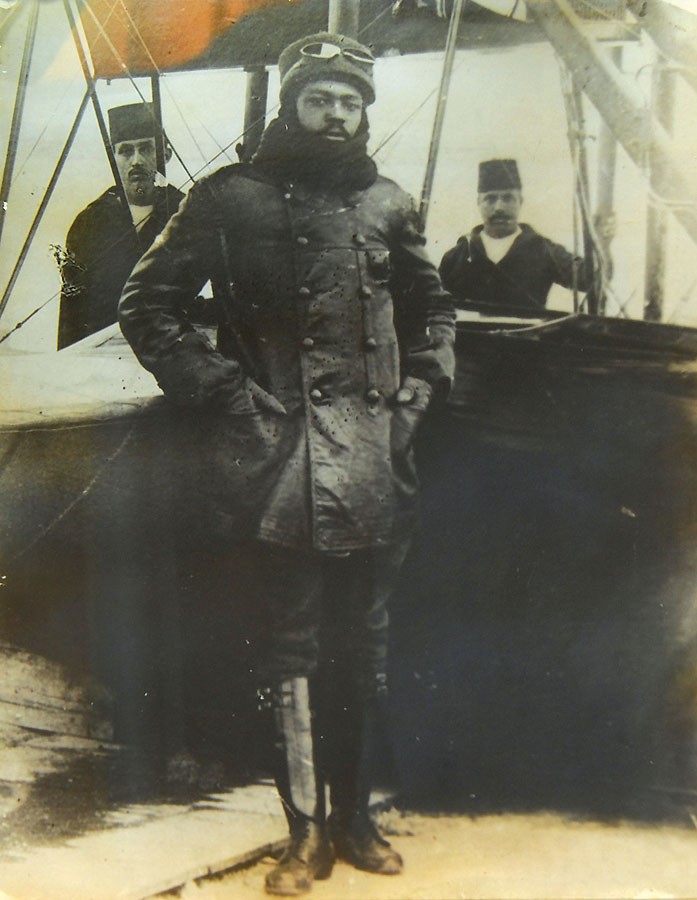

Graduating in 1908 as a mülâzım-ı evvel (navy lieutenant), he began his naval career. But a new force soon captured his attention: the skies. Military aviation was just beginning in the Ottoman Empire, which founded its first naval flight school, the Deniz Tayyare Mektebi, in Yeşilköy in 1914—the same location where the few surviving photographs of him were taken. Aviation was not yet closed off by rigid social or racial barriers. It was a new field, open to navy technicians—especially those skilled in modern mechanics. Ahmet Ali fit the profile perfectly.

This transition from sailor to pilot was no small feat. It marked a double ascent: in military rank and public imagination. The aviator, in the Empire as elsewhere, symbolized progress, courage, mastery of the invisible. For a Black man, this position went beyond the personal. It became a silent subversion. While colonized Africa was seen as “grounded,” passive, and lacking in technological command, Ahmet Ali took flight.

On November 11, 1916, he officially became a military pilot. He was among the very first in the Ottoman Empire to receive his wings. More than that: he was the first Black man in the world to join a regular air force as a military pilot. At that time, Eugene Bullard had yet to receive his French pilot license, William Robinson Clarke was barely in training, and Domenico Mondelli was serving in a paramilitary Italian context.

But Ahmet Ali didn’t stop at flying. On February 14, 1917, he was promoted to Yüzbaşı (captain) and sent to Germany for advanced aviation training. In Berlin, he encountered a different relationship to war technology—and to race. The experience reinforced his unique posture: he was neither a colonized man trained by the West, nor a “useful Black” promoted for symbolic purposes. He was an autonomous officer—Turkish and African, Ottoman and modern.

Back in Anatolia, he was assigned to the Izmir Naval Aviation Unit with a new nickname recorded in the registers: Kara Kartal—”Black Eagle,” or more literally, “Black Iron Eagle.” The name was more than martial flair—it was a statement. In a world where Black figures were relegated to colonial infantry or silence, he soared. Yet history long refused to grant him the altitude he deserved.

The image of a Black pilot in the Ottoman army at the beginning of the 20th century might surprise many. In the popular imagination, Afro-descendants are often associated with sub-Saharan colonies, European empires, and roles as subjugated soldiers or laborers. Yet the Ottoman Empire had its own African population and its own racial dynamics—different, though not necessarily more inclusive. To understand Ahmet Ali Çelikten’s place in the Ottoman military, one must first deconstruct persistent clichés.

Far from being ethnically homogeneous, the Ottoman Empire was an imperial mosaic: Turks, Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Bosniaks, Circassians—and Afro-descendants—coexisted within stratified social structures that were more flexible than Western colonial racial regimes. Slavery was abolished relatively late—around the turn of the 20th century—but many freed Africans had already integrated into urban and military life.

In cities like Istanbul, Smyrna, or throughout Anatolia, the Zenci (a term designating both skin color and African origin) formed communities often linked to domestic, religious, or military service. Many served in palaces, mosques, or Sufi orders. Some rose further, especially in maritime units or technical schools, where skill could still trump rigid racial hierarchies.

The Ottoman army, though dominated by Turkish and Caucasian elites, did not explicitly bar Afro-descendants. Social barriers made it difficult—but not legally impossible. Thus, the presence of a Black officer, and eventually a pilot, was not entirely unheard of—though still rare. Ahmet Ali was not a radical anomaly but rather the extreme realization of a seldom-seen possibility.

In Ottoman military culture, the image of the African soldier was neither that of the European “tirailleur” nor of the “savage” to be civilized. It hovered between loyal servant and tolerated outsider. This ambiguity allowed for certain pathways—but rendered any spectacular rise politically invisible. Perhaps this is why, despite his service record, Ahmet Ali never became a public figure in the coming Turkish Republic.

It’s also important to note that, within the Ottoman imaginary, religious hierarchy often trumped racial categorization. A Muslim African loyal to the state could, in theory, advance further than a Christian from Eastern Europe or a Jewish subject—who were considered millets (non-Muslim communities), tolerated but distinct. This religious logic, more than racial bias, enabled Ahmet Ali to access aviation’s closed circles.

Yet this did not mean the absence of prejudice. To be Black in the Ottoman Empire—even as a loyal Muslim—was to carry a visible mark of otherness, always at risk of being invoked or erased. In this sense, Ahmet Ali was heir to a long tradition of unrecognized loyalty: that of the Empire’s Black citizens, invisible in imperial murals but omnipresent on the margins of power.

This context sheds light on the uniqueness of his rise. He was not a pawn in an inclusion strategy. He was the exception born from a crack in the system. And the official histories—Ottoman and Republican alike—rushed to forget this anomaly.

A global aviation pioneer

In the pantheon of military aviation, Black figures are rare—and often recognized belatedly. Eugene Bullard, the Afro-American pilot who flew for France in World War I, is usually presented as “the first Black aviator in history.” That is historically incorrect. For three years before Bullard earned his pilot’s license in 1917, another man of African descent had already taken to the skies: Ahmet Ali Çelikten, certified as an Ottoman military pilot in 1914.

This precedence matters. It reveals how official history—shaped by imperial centers in Europe and America—has systematically marginalized Black trajectories outside the colonial framework. Ahmet Ali did not serve in a colonial army; he served a Muslim empire—decaying, perhaps, but still sovereign. And that may be why he was condemned to oblivion: he fit no convenient category of Western narrative.

The timeline is clear. The Yeşilköy naval aviation school opened in June 1914. Ahmet Ali, already a navy officer trained in mechanics, was among its first trainees. By November 1916, he was officially recognized as a military pilot. Promoted to captain in February 1917, he preceded Eugene Bullard, William Robinson Clarke (Jamaica, Royal Flying Corps), and Domenico Mondelli (Eritrea/Italy) in becoming a wartime pilot.

Yet while Bullard has received posthumous recognition—French military medals, U.S. postage stamps, statues, documentaries—Ahmet Ali remains in the shadows. Even modern Turkey has rarely celebrated him. Why?

Because he was a product of a vanished world: a non-European empire where technical modernity did not rely solely on the West. Because he was Black but had no ties to American slavery or African colonies. Because he was Muslim, in a global context where Islam is often portrayed as antithetical to technological progress.

His story exposes a major bias in historiography: the dominant narratives’ failure to acknowledge the plurality of Black trajectories, especially when they emerge outside European colonial systems. It was not just racism that erased Ahmet Ali—it was the eurocentrism built into Black memory itself.

And yet his existence is well-documented. His service records, photographs in flight uniform, Turkish military archives, and testimonies from contemporaries all confirm: he was indeed the first Black pilot in world military history.

This recognition upends our understanding of aviation’s early days. It shifts the center of gravity in the narrative. It reminds us that Black historical figures didn’t all come from resisting Europe or from colonial backgrounds. Some, like Ahmet Ali, took flight from other worlds—unacknowledged, but powerful.

As Europe plunged into World War I, the Ottoman Empire—though weakened—sided with Germany in hopes of regaining strategic clout after major territorial losses. Aviation, still in its infancy, quickly became a vital tactical tool. In this context, Ahmet Ali Çelikten entered the active phase of his career—not just as a pilot, but as a military actor within an empire at war.

Unlike pilots from major industrial powers, Ottoman aviators operated under rudimentary conditions: few aircraft, scarce spare parts, limited training—yet remarkable versatility. Recognized for his technical skill, Ahmet Ali was assigned reconnaissance and logistics missions over critical zones, notably during the Dardanelles campaign (Gallipoli). He did not fly fighter squadrons, but played a key role in naval coordination and aerial coastal surveillance.

In December 1917, he was sent back to Germany to further hone his aeronautical skills. This training was more than symbolic. Germany, locked in attritional warfare, aimed to turn Ottoman officers into transmitters of its technological expertise. Ahmet Ali returned more seasoned—and one of the only Black officers across the entire German-Ottoman alliance. In military archives, he is recorded with a singular title: “Çelik Kara Kartal”—“The Black Steel Eagle.”

Upon his return, he was posted at the İzmir Naval Air Unit, where he flew surveillance missions and helped train young pilots. Even as the Empire began to fracture under external and internal pressure, Ahmet Ali chose to stay the course. He refused the offers of safe exile extended to disillusioned Ottoman elites by foreign powers.

His sense of duty—rooted in an Ottoman view of military honor—carried him into a new chapter: the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923). With the fall of the Empire, the country lay fragmented under foreign occupation. A new struggle emerged, led by Mustafa Kemal and the nationalist movement. It was a war without fixed front lines, where aviation, though limited, played a discreet but critical role.

Ahmet Ali joined the nationalists. He was stationed at the Konya Air Base and participated in a strategic mission: recovering and relocating aircraft stored in former Ottoman hangars to Amasra, on the Black Sea. These planes—transported covertly—would enable reconnaissance and defense of key coastal positions for the fledgling nationalist forces.

This turning point—from imperial collapse to republican foundation—was crucial for Çelikten. He became one of the few Afro-Ottoman officers to transition into the Turkish Republic while retaining his rank and responsibilities. In doing so, he embodied an often overlooked continuity: that of a Black soldier who served both political incarnations of his homeland, unwavering in his loyalty.

When the 1918 armistice sealed the Ottoman defeat, the empire was carved up by the Allies: Istanbul came under British control, Smyrna fell to the Greeks, and Anatolia caught fire. This was no longer merely a war over borders—it became an existential battle. In this chaos, Ahmet Ali made a clear choice: to reject resignation and embrace the fight for Turkish sovereignty.

Aviation in this setting was not a tool of technological dominance, as in Western powers. It was a rare, precarious, yet decisive resource. The nationalists had to improvise an army from scattered remnants. Among their most urgent needs: planes—and skilled pilots. Ahmet Ali was one of the few professionals still in service, and, above all, a man of trust: loyal, competent, untainted by imperial collaboration.

His most critical mission came in 1922: he was sent to the small port of Amasra to oversee the exfiltration of aircraft from abandoned military hangars. The goal: conceal them from occupying forces, restore them, and use them to secure the strategic northern Anatolian coast. These were not glamorous air battles, but extremely high-risk flights—under harsh weather conditions and using deteriorating equipment.

From Amasra, the recovered planes were deployed to monitor Greek troop movements, intercept suspicious maritime supplies, and provide vital intel to Kemalist commanders. Ahmet Ali was not just a pilot—he became a de facto operational coordinator for the nationalist air force, a sort of makeshift technical director for a fledgling free aviation force.

His discreet yet strategic role earned him recognition at the highest levels. In 1924, the newly proclaimed Turkish Republic awarded him the Medal of Independence No. 480, signed personally by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. This rare honor for a Black officer in a reconstituting nation was a tacit acknowledgment: here was a man who, without seeking glory, had steadfastly served a national cause.

Yet in the hyper-centralized, Western-leaning Republican Turkey, the image of a Black pilot from the imperial era did not fit the new founding myths. Over time, Ahmet Ali was pushed to the margins of history. He nonetheless continued his military career, contributed to the founding of the Air Undersecretariat (Hava Müsteşarlığı) within the Ministry of Defense, and retired in 1949 with the rank of colonel.

What official history remembers—sparsely—is neither his strategic role in Amasra, nor his training in Germany, nor his early engagement in 1914. What is forgotten—deliberately or not—is that he was the only Afro-descendant aviator to serve both the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Mustafa Kemal; a direct witness to the transition between worlds, without ever betraying his integrity.

It is time, now, to return him to the center of collective memory.

The black eagle and the stolen memory

Ahmet Ali Bey (Çelikten), a Nigerian, first Black fighter pilot in the world, Izmir, 1922

The story of Ahmet Ali Çelikten is both exceptional and revealing. Exceptional, because he was the first Black pilot in military history—a discreet pioneer at the heart of a collapsing empire and an emerging republic. Revealing, because it exposes the mechanisms of erasure that target Black figures outside the classic colonial framework—those who did not fight the white oppressor but loyally served a non-European state also vanish from the global narrative.

Ahmet Ali’s trajectory defies every stereotype: he was neither a freed slave nor an exotic infantryman, nor a folklorized hero. He was a technician, a soldier, a patriot (and a Black man) who operated at the highest levels of a state apparatus. He is the living refutation of the idea that Black people only entered technological modernity through the European colonial door.

That his name remains absent from history books, school curricula, and official commemorations is symptomatic of a deeper issue: the struggle to incorporate Black paths that don’t fit dominant narratives—be they Western or nationalist.

Restoring Ahmet Ali Çelikten to his rightful place is not merely correcting a historical oversight. It is widening our lens on modernity, on diasporic Africa, on the history of technology and nations. It is a reminder that Black wings of history didn’t only spread over cotton fields or colonial squadrons—but sometimes, too, from an Ottoman sky—laden with forgetfulness, but also with promise.

Notes and References:

- Nicolle, David. The Ottoman Army 1914–1918. Osprey Publishing, 1994. Men-at-Arms Series.

- Posta. “Dünyanın İlk Siyahi Pilotu: Arap Ahmet – Parts 1 to 4”, Posta, March 2011.

- Johnson, Mark. Caribbean Volunteers at War: The Forgotten Story of the RAF’s “Tuskegee Airmen”. Pen and Sword, 2014.

- Nicolle, David. Over the Front, Vol. 9, No. 3, Fall 1994.