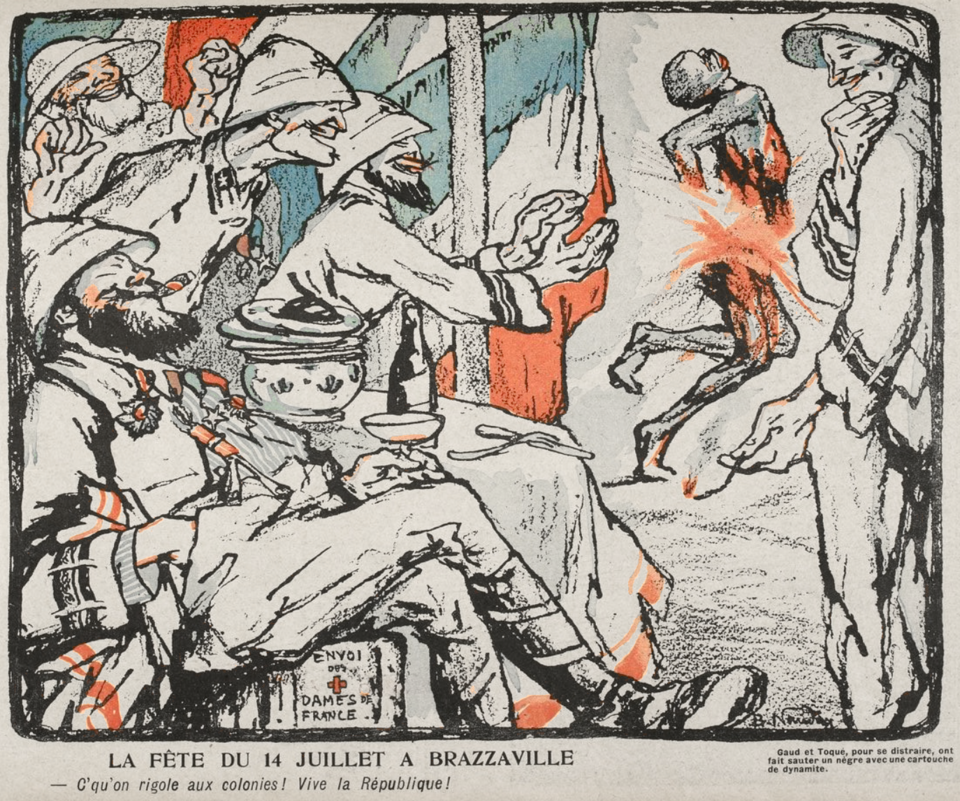

On July 14, 1903, in Fort-Crampel, a Black man was executed with dynamite by two French colonial agents. This was not a blunder, but a stark reflection of a colonial system built on violence and impunity. A look back at the Gaud-Toqué affair, when the Republic detonated its own humanist façade.

The silence before the blast

Fort-Crampel, July 14, 1903. While the French Republic parades under tricolor flags, celebrating the storming of the Bastille, three African men rot in a grain silo in a remote clearing of Ubangi-Chari (present-day Central African Republic). No trial. No charges. Only the vague instruction of a fever-ridden colonial administrator: “Do whatever you want with them.” Two are released. The third, Pakpa, will not survive. He is not shot. He is not strangled. He is blown up.

It is Fernand Gaud, a clerk for native affairs, who orchestrates the execution. A stick of dynamite, normally used for fishing, is tied around the man’s neck. Then, in a gesture as technical as it is expedient, the fuse is lit. Seconds later, nothing remains of Pakpa but a bloody memory. And a message:

“Heaven’s fire fell upon the one who refused friendship with the white man.”

This phrase, quoted during the trial, is not a metaphor. It is the signature of a colonial act, a violent synthesis of imperial logic. Pakpa was not killed for any crime. He was executed because he embodied a diffuse threat: that of a Black man who might disobey, betray, or evade control. He was reduced to a pedagogical function, a deterrent example. It wasn’t the man who was killed — it was the population being disciplined.

The case could have been buried, like so many others, in administrative margins. An accident, an excess, a misstep. But this time, an investigation emerged. Delayed, sabotaged, incomplete — but enough to reveal what France preferred to ignore: that beneath the garments of the Republic, the Empire operated under different rules. Racial. Absolute. Bureaucratic.

Because this execution was not a moment of madness. It wasn’t an “isolated incident.” It was a programmed killing, carried out in an organized lawless zone, by men trained to uphold total power, in a system where Black life weighed less than a stick of dynamite.

Pakpa — a name so rarely spoken — stands for far more than the victim of a colonial crime. He is a symptom of an empire with no witnesses, no fair trials, no return. An empire where silence always precedes the explosion — and where the explosion is often the only answer to a life deemed too much.

The bare-handed empire (architecture of impunity)é)

They were neither tyrants nor seasoned war criminals. Just two civil servants on assignment. Fernand Gaud, 29, a failed pharmacy student relegated to Africa after a chaotic path. A second-rate man, frustrated, poorly integrated into the colonial hierarchy but zealous enough to make himself indispensable on the margins. Georges Toqué, 24, a colonial administrator fresh from the Colonial School, embodying the Republic’s missionary civil servant. Two faces of authority: one rustic, the other bureaucratic. Yet both endowed with the same absolute power.

Their complementarity is chilling. Toqué holds the title, the education, the republican legitimacy. Gaud holds the brute initiative, the familiarity with on-the-ground violence. Together, they run Fort-Crampel like a lawless territory, where their authority meets no limits. No judge. No credible witness. No recourse for the natives.

Their story reveals the insidious effects of the French colonial infrastructure: remote posts entrusted to men too young, too free, too steeped in the idea that Black people do not have the same rights. At the Colonial School, Toqué learned to manage “primitive populations” with “firmness and method.” He applies that. Gaud needed no training. He improvises, like many colonial agents sent without psychological preparation into environments where racial domination was the only compass.

What’s most chilling is their composure. Before and after Pakpa’s explosion, they show neither panic nor remorse. Toqué does not punish Gaud. He disapproves of the method, he says — but not severely. Gaud, for his part, justifies himself confidently:

“It was to make an impression. To dissuade.”

They speak of a human being as a misplaced pawn on the colonial chessboard. In their eyes, this was not murder — it was risk management.

Understand this: within the framework of colonial administration, they were not deviants. They were cogs. What one suggested and the other carried out fit within a logic tolerated, sometimes encouraged, by the silence of their superiors. They didn’t “misbehave.” They acted as one acts in a zone of exception.

Fort-Crampel is not a cursed place. It is a microcosm of the Empire, a distilled example of what the Republic does when no one is watching. A remote outpost with no judiciary, no press, no observers. No prison, no court, no lawyer. Authority rests solely on the will of the white official.

Here, the colonial equation operates in its rawest form: the natives are not citizens, but managed resources. Porter labor becomes permanent servitude. Taxation, a levy by saber. Disobedience, an instantly punishable crime. Men are bodies. Women, hostages. Children, living guarantees. Rubber is the goal. Everything else is variable.

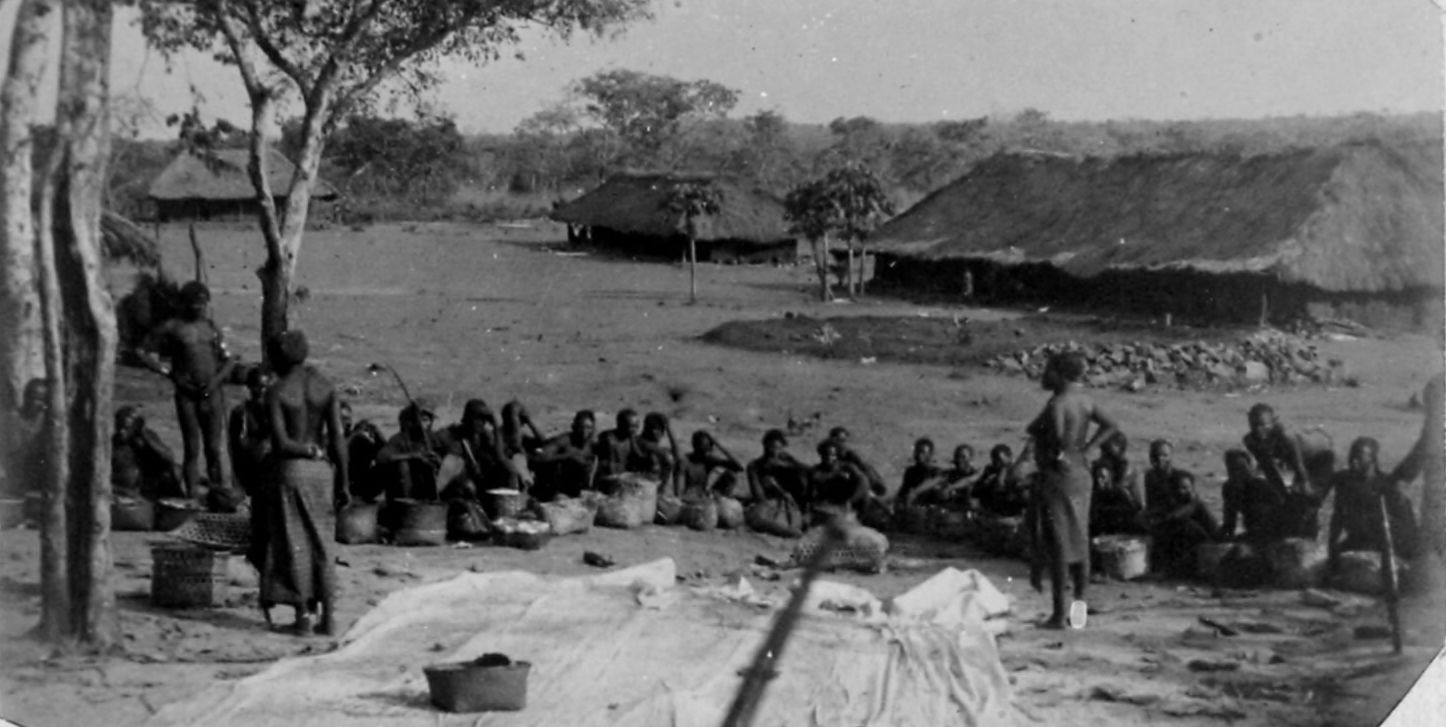

Brazza’s later testimony is damning: hostages crammed into a dark hut, sixty-six people locked up without light, twenty-five dead in twelve days. Survivors emerge emaciated, unable to walk. At Fort-Crampel, hunger, fear, and humiliation are not errors. They are tools.

Dynamite, in this context, is no aberration. It is the epitome of colonial logic: maximum efficiency, brutal symbolism, minimal cost. A Black man suspected of betrayal? No need for an investigation. One charge, one fuse, one example. Gaud does not innovate: he optimizes. He embodies the colonial manager — turning horror into method, method into routine.

Fort-Crampel is not a stain. It is a precipitate of the Empire: an enclave where the Republic suspends its principles to better assert its domination. And the civil servants who operate there are not bad apples. They are the exact product of the system that sent them.

The Execution of Pakpa (A Programmed Murder)

There was no trial. No outcry. No resistance. Just a phrase, whispered in a sweltering room by a fever-stricken colonial administrator:

“Do whatever you want with him.”

On July 14, 1903, in that remote post of Fort-Crampel, this phrase opened the way for one of the most sinister acts of French domination in Equatorial Africa.

Pakpa, a native arrested days earlier and accused without proof of betrayal, is led to a clearing. Rather than organizing a firing squad (too formal, too military), Fernand Gaud chooses dynamite. He ties the cartridge around the prisoner’s neck, lights the fuse, steps back, and lets the explosive do its work. The man is literally disintegrated. His body vaporized. The horror is not collateral — it is the message.

This is not an execution — it is a lesson. Gaud would later say he wanted to make an impression: “Astonish the natives.”

He doesn’t use the word “punish,” or “protect,” or even “neutralize.” He says “impress.” Instill fear. Establish domination through shock value. To him, brutality is only valuable if it’s seen, known, repeated in villages. Murder becomes a teaching tool.

And to justify his act, Gaud even invokes a biblical imaginary:

“Heaven’s fire fell upon the one who refused friendship with the white man.”

As if colonial power were not only political, but sacred. As if the Republic had, somewhere in the clouds, a divine mandate.

At Fort-Crampel that July 14, the republican pact is not celebrated. It is inverted. Equality is pulverized with Pakpa’s body. Fraternity is reserved for whites. And liberty is inscribed through terror. The explosion is not an isolated detonation: it is the founding act of a colonial order that requires no speeches, no laws, not even confessions. One gesture is enough. One burst. One silence after the noise.

After the execution, nothing happens. No incident report. No commission. Not even a note to Brazzaville. The colonial administration absorbs the act as one absorbs a logistical hiccup. Pakpa no longer exists. And those who killed him don’t even hide it.

Georges Toqué — the man who authorized the crime with a shrug — does not flinch. He doesn’t write a word of remorse. When he hears the details (the dynamite, the barbaric method), he grimaces, but takes no action. He considers the matter closed. Pakpa has no name in the registers. Therefore, he is not entitled to justice.

Fernand Gaud, for his part, almost brags. He recounts the explosion. He speaks of the silence that followed. He theorizes. He turns horror into pedagogy. To him, the act is an example of “colonial efficiency.” And if some later express outrage, it’s, in his words, because they “don’t understand the realities on the ground.”

It is only through an improbable chain of events that the affair reaches the metropole. Letters, indirect witnesses, the beginnings of a scandal. And above all, the return of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, commissioned by the Republic to investigate abuses in the Congo. Accompanied by young scholar Félicien Challaye, he gathers testimonies, confronts silences, and pieces the puzzle together.

Yet even then, impunity prevails. The trial is relocated to Brazzaville, far from Paris and its political commotion. Gaud and Toqué appear not as war criminals, but as civil servants who mishandled an “exceptional situation.” One is convicted of “unpremeditated murder.” The other of “complicity.” Five years in prison. And even then — with mitigating circumstances.

In the courtroom, colonists are outraged. Not at the murder, but at the verdict. To them, the problem is not the violence — it’s that it was judged.

“Too much value is placed on a native’s life,” say some notables. That phrase encapsulates the colonial philosophy of the time. Africa was not worth a man — let alone a fair trial.

The execution of Pakpa did not shock the Empire. It barely raised questions. It only disturbed because it was visible. Because it was recounted. And because, this time, the body didn’t vanish without a trace. But the system remained untouched.

Brazza, the man who saw

In 1905, under pressure from an outraged press and anxious parliamentarians, the French state sent a legendary figure to “shed light” on the situation in French Congo: Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. A former explorer and iron-hearted humanist, he was tasked with assessing the living conditions of Indigenous populations after persistent rumors of violence, abuse, and extortion. In truth, what was expected of him was a public relations operation. A façade mission. A smokescreen.

But Brazza was not a man of façades. From his arrival in Libreville, he realized everything was being done to stop him from investigating. Deliberate delays, transportation refusals, frozen funds. His assistant Charles Hoarau-Desruisseaux was even ordered to stay away. Forbidden from joining the mission in the field. Brazza was isolated, monitored, obstructed at every turn. It was an elegant, deadly bureaucratic sabotage. They didn’t want him to see.

But he saw anyway.

Despite illness (diarrhea, continuous fevers, extreme weight loss), he pushed forward, supported by his wife Thérèse and a few loyal companions. At every stage, he wrote, he recorded, he questioned. And what he uncovered defied belief.

In the heart of French Equatorial Africa, Brazza found a colonial machine powered by pure terror. In Bangui, he entered a hut six meters long, without windows or ventilation, where 66 hostages were crammed. Women, children, elders. They were not accused of any crime. They were there to force the men of the village to meet their rubber quotas. They were human pawns. Instruments of pressure.

In twelve days, twenty-five of them died. Their bodies were thrown into the river. Survivors were released in a state of utter collapse. Several died shortly after. One woman returned home while breastfeeding another’s baby. At Fort-Crampel, Brazza discovered an infrastructure comparable to a prelude of a concentration camp. Hostages were penned in inhuman conditions. Women paddled alone in canoes, beaten if they slowed down. Men were nowhere to be found: disappeared, on the run, or already dead.

And there was more. At the entrance to a path, he stumbled upon an abandoned skeleton — dried out, forgotten. He ordered it buried according to local customs. A small act, perhaps, but symbolically immense: for the first time, a high-ranking representative of the Republic acknowledged the humanity of a Black corpse.

His report was clear, methodical, damning. In it, he wrote:

“This is not an isolated event. What I have seen is evidence of a system. The [colonial] department ignores — or pretends to ignore — the reality of the methods used.”

His mission companion, philosopher Félicien Challaye, published searing columns in Le Temps. He described the starving hostages, the nameless children, the tortured women, the emptied villages. He named the horror. He made it public. He refused euphemism.

But in Paris, the administration did everything it could to bury the report. It would not be published in full until a century later — in 2014. In the meantime, Brazza died. Worn down, broken, ignored. He refused to be carried in a tipoye (a sedan chair used by sick colonials), and walked to the last boat, supported by his wife. He died on September 14, 1905, in Libreville. Alone. Without honors. Without answers.

Brazza had seen. And what he saw (what France refused to see) was that its Empire stood upright only because it leaned on corpses.

A trial for the sake of appearances… but for whom?

When the case finally surfaced, the French state found itself trapped by its own image. It was impossible to ignore the execution of Pakpa after Brazza’s report. Impossible to pass it off as a local incident. But trying two colonial agents meant casting a harsh light on the machinery of Empire. So a more subtle maneuver was needed: hold a trial, but without judging the system. Accuse the men, not the institution. Punish without questioning itself.

It was in this context that the trial of Fernand Gaud and Georges Toqué opened in Brazzaville in August 1905. The location was strategic: by keeping it far from Paris, media pressure was minimized. Only one journalist was present — Félicien Challaye, the same man who had accompanied Brazza and published unflinching testimonies in Le Temps.

The hearing began. Gaud, ill, feigned lethargy. He said little, dodged questions. Toqué defended himself passionately: he condemned the conditions of his post, the contradictory orders, the lack of judicial infrastructure. He admitted to forced labor, hostage-taking, corporal punishment. He admitted, without blinking, that families had been starved to ensure obedience. In his view, this was not cruelty. It was administration.

At no point were the foundations of the system questioned. The trial’s core concern was not the humanity of the act, but the chain of command. Who gave the order? Who went too far? Toqué accused Gaud of acting alone. Gaud claimed he had received implicit approval. They blamed each other, each trying to wriggle free.

The court did not clearly decide. On August 26, 1905, Gaud was sentenced to five years in prison for unpremeditated murder, Toqué to the same for complicity. At the time, these sentences seemed severe to the colonists, who denounced “excessive judicial zeal over a native’s life.” In the courtroom, several commentators whispered that the Republic had “yielded to Parisian pressure.”

But the sentence, heavy as it may seem, did not touch the imperial edifice. No investigation was launched into forced porter labor. No superiors were summoned. No protocols were changed. Gaud and Toqué were framed as deviants, exceptions — even though their actions fit a well-documented, accepted, institutionalized colonial normalcy.

The trial became a ritual of self-cleansing for the Republic: it condemned two men in order to absolve its Empire. It offered something to the press, calmed the parliamentarians, reassured public opinion. The crime was judged. Order restored. The stage remained untouched.

And Pakpa? No mention of his relatives. No status as a recognized victim. No monument, no plaque, no memory. He was not the heart of the case. He was its invisible pretext.

This trial did not judge a murder. It sealed a silence.

Dynamited memory, blind republic

Pakpa’s story is not taught. It appears in no textbook, no national commemoration, no monument. His name is not engraved, his suffering not acknowledged, his execution by dynamite treated as a footnote. Yet he embodies what official historiography refuses to name: deliberate cruelty as a tool of governance, dehumanization as a pillar of colonial authority, and silence as a state strategy.

French colonialism was not only a tale of “greatness” or a “civilizing mission.” It was, in its most remote outposts like Fort-Crampel, a bureaucracy of humiliation, run by young white technocrats convinced they were enforcing order. The Republic did not lose its way on that day in July 1903. It worked exactly as intended. That day, it didn’t malfunction — it revealed its double face.

And perhaps that is the most unbearable part: the apparent banality of the perpetrators. Gaud, a failed pharmacist. Toqué, a young graduate. No monsters. No fanatics. Just ordinary men invested with extraordinary power, in a system without safeguards. And when that power turned into the right to decide who lived or died, no principle, no law, no morality intervened.

What Brazza discovered was not an exception. It was an architecture. An administrative, logistical, political structure; where terror was rational, corpses were counted, punishments normalized. An imperial machine. He said it. He wrote it. He died for it. And it took a century to publish his report.

Even today, this memory lies in ruins. Dynamited, like Pakpa. Erased beneath the varnish of official discourse. But remembrance is not about “repentance.” It is about rejecting lies, refusing silence in place of justice. Refusing that history only retain the names of the executioners — and never those of the victims.

So we must say Pakpa. Write him. Remember him. Not as a tragic figure, but as a man killed by a system that believed itself eternal. And ask, on the threshold of the 21st century, a question with no easy answer:

How many Pakpas has French history forgotten?

Sources:

- The Brazza Report. Congo Investigation Mission: Report and Documents (1905–1907), ed. Le Passager Clandestin, 2014.

- Gustave Regelsperger, The Gaud-Toqué Affair, in: Revue Universelle, Larousse, 1905.

- Le Temps, Sept. 23 & 26, 1905 – courtroom articles.

- Edward Berenson, The Politics of Atrocity: The Scandal in the French Congo (1905), Historia y Política, 2018.

- Daniel Vangroenweghe, The ‘Leopold II’ Concession System Exported to French Congo, Revue Belge d’Histoire Contemporaine, 2006.

- Pierre Mollion, Portering in Ubangi-Chari (1890–1930), Revue d’Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine, 1986.

- Benjamin König, The Brazza Report, a Portrait of French Colonial Barbarity, L’Humanité Magazine, No. 942, February 2025.

Summary

- The Silence Before the Blast

- The Bare-Handed Empire (Architecture of Impunity)

- The Execution of Pakpa (A Programmed Murder)

- Brazza, the Man Who Saw

- A Trial for the Sake of Appearances… But for Whom?

- Dynamited Memory, Blind Republic

- Sources