Sickle cell disease is the most common genetic illness in France—and yet one of the least talked about. Through a historical and political lens, this article explores what this condition reveals about our relationship to Black bodies, colonial memory, and health inequalities. A powerful reflection on the urgent need to bring visibility to a suffering long kept in the dark.

“Silence is a pain that goes unspoken. Sickle cell disease is one of those.”

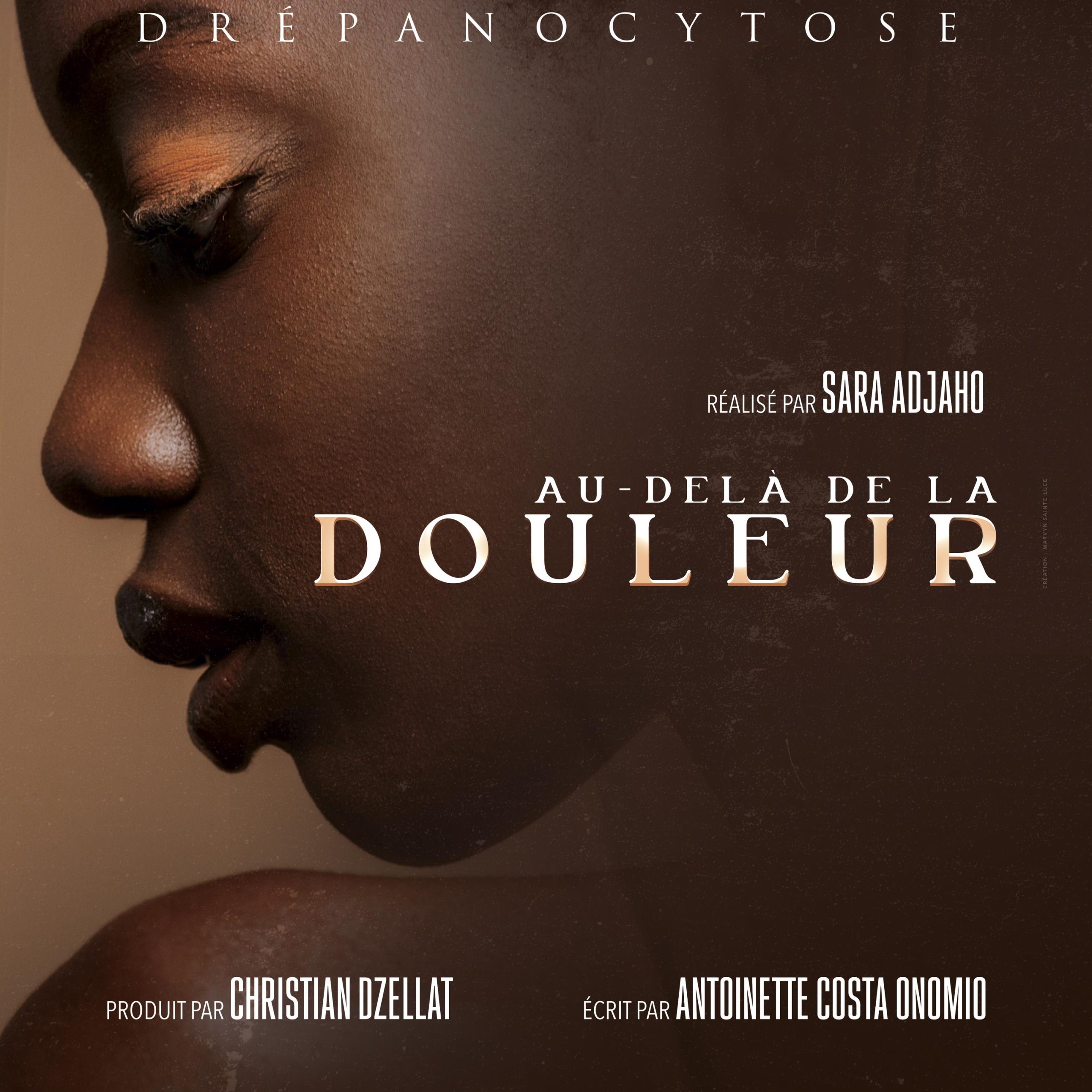

— Antoinette Costa, transplant recipient, survivor, and protagonist of the film Beyond the Pain

More than 30,000 people in France live with sickle cell disease. Yet their pain remains voiceless in public discourse. No national campaign. Minimal screening beyond “target zones.” Not a single minister speaking out. As if the disease were embarrassing. As if it were inconvenient because it affects bodies the Republic barely acknowledges.

The most prevalent genetic illness in the country is also the most ignored. A tragic paradox, whose roots lie not in statistics or science, but in the long history of racial inequality in healthcare. What sickle cell disease indirectly reveals is how the Republic manages Black bodies.

The documentary Beyond the Pain aims to disrupt this silence. Through the voice of Antoinette, a young Guadeloupean woman who received a bone marrow transplant, an invisible memory finally speaks. The memory of silent pain, neglected emergencies, canceled appointments due to lack of resources. The memory of children raised not to complain. The memory of a medically abandoned people.

What if sickle cell disease were not only a health issue?

What if it were also a mirror reflecting our collective blind spots?

A metaphor for how Afro-descendant populations are treated: present, but invisible; suffering, but forgotten; alive, but unheard.

A disease born in Africa… to survive malaria

Before it became a matter of statistics, sickle cell disease was a story of survival written into the African genome. This genetic mutation—often described as an “anomaly”—was originally a natural adaptation to a far older scourge: malaria.

For millennia, malaria has claimed countless lives in sub-Saharan Africa. In response to this deadly pressure, nature fought back. A mutation appeared in the hemoglobin gene. Passed on by only one parent, it does not cause illness—but provides partial protection against malaria. The carrier lives, survives, and passes the gene on.

But when both parents are carriers, the child inherits two copies of the mutated gene—this is when sickle cell disease manifests. A cruel inheritance, born of an invisible battle between parasites and blood cells.

What history labeled as a “disease,” genetics might instead call: a trace of resistance.

Sickle cell disease is not, as some still claim, a “Black disease,” but an evolutionary response that emerged in the tropics—where mosquitoes killed more people than war. It also exists, in other forms, among Mediterranean, Indian, and Middle Eastern populations.

But it was the transatlantic slave trade, by deporting millions of Africans to the Americas, that spread this gene of survival across the ocean. Guadeloupe, Haiti, Brazil, the United States—everywhere enslaved Africans built empires with their sweat, the sickle cell gene took root. Blood traveled, carrying with it ancestral pain.

In the West, this genealogy has been forgotten. What was once an adaptive logic has become an invisible stigma. History has been whitewashed, along with the memory of what this gene truly represents: a story of resistance, of suffering, of African heritage.

Sickle cell disease, far beyond a medical condition, is a biological archive. A trace etched in the blood of those who were deported, ignored, then half-heartedly cared for.

France and sickle cell disease (between ignorance and neglect)

There is something quietly colonial in France’s handling of sickle cell disease. A kind of unspoken discomfort, an organized invisibilization—as if acknowledging the disease meant acknowledging Black people. Their presence. Their pain. Their full citizenship.

Since 2000, France has implemented targeted neonatal screening. In short: only babies born in “at-risk” regions (Île-de-France, the Antilles, Réunion, etc.) or from “high-prevalence” backgrounds are systematically tested at birth.

The result: a two-tier healthcare system.

A white child born in Paris won’t be tested—even if she could be a carrier.

A Black child will be tested… but this does not guarantee proper medical follow-up.

This targeted approach, under the guise of efficiency, essentializes origins and ignores the realities of a mixed French population.

And yet, the data are known:

- Around 30,000 people live with the disease in France

- 500 new cases are diagnosed every year

- In Île-de-France, 1 in every 400 births is affected

These figures should be enough to prompt a national mobilization—as was the case for other genetic or infectious diseases. But here, there is no grand public plan, no mass awareness day (aside from a few activist groups). Just a white silence over Black pain.

This neglect is not neutral. It follows a long history of medical racism—described by Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks, and echoed today in the testimonies of sickle cell patients:

- Pain minimized in emergency rooms

- Underdosed treatments

- Poorly trained doctors

- Endless diagnostic wandering

“I lost count of how many times they told me I was faking it. That I was ‘too young to be in that much pain.’”

— Sofia, 26, with SS sickle cell disease

Medicine in France has never been neutral. It has often served as an arm of the State, quietly applying a form of soft eugenics: don’t treat what makes people uncomfortable.

Breaking the silence is the first step toward healing

Lacking institutional attention, it is the patients themselves, their families, and Afro-descendant voices who have begun to speak out. Because waiting for recognition that never comes means dying twice: first from the disease, then from indifference.

Sickle cell disease long remained hidden in hospital corridors, behind the closed doors of pediatric wards. But in recent years, a shift has occurred. Patients are speaking. Testifying. Writing. Organizing. As with the fights against AIDS, breast cancer, or asbestos-related diseases, the voice of the forgotten is rising.

Through patient testimonies, a form of resistance is taking shape: making the invisible visible, turning endured pain into political force.

The documentary Beyond the Pain follows in this tradition. It’s not just a medical account. It’s a political act, a filmed cry that says:

“We are here. Our bodies matter as much as anyone else’s.”

In this light, producing such a film is a powerful gesture.

A democratic gesture.

An Afro-conscious gesture.

A public health gesture.

In Africa, the Caribbean, and the diasporas, sickle cell disease is ever-present—yet rarely included in political agendas. Yet it could become a cornerstone of South-South healthcare cooperation, a matter of medical sovereignty and racial justice.

This fight for recognition is not only medical. It is symbolic. It reflects what society is willing to see—or chooses to leave untreated.

Healing is not just about treating symptoms. It means naming injustice. Acknowledging it. Listening to the voices that are never heard.mer les injustices. Les reconnaître. C’est écouter les voix qu’on n’entend jamais.

Healing begins with light

Sickle cell disease is not only a blood disorder. It is a disease of erasure.

Erasure of pain.

Erasure of lives.

Erasure of histories.

But in every testimony, in every stifled cry in the ER, in every moment when a doctor doubts the legitimacy of a complaint, there is a collective memory that resists. That demands justice.

Beyond the Pain is not here to cure. It is here to show. To reveal. To remind us that behind every sickled cell, there is a life, a story, a dignity.

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

— African proverb quoted by Chinua Achebe

It is time for the lions to speak. For children with sickle cell disease to have a future without pain or shame. For healthcare providers to be better trained and equipped. For policymakers to finally open their eyes to this silent scandal.

Making sickle cell disease visible is not just a matter of public health.

It is a bold affirmation that Black lives matter. Here. Now. Always.

Main Sources

- INSERM (National Institute of Health and Medical Research)

➤ www.inserm.fr - World Health Organization (WHO)

➤ www.who.int - Santé Publique France

➤ www.santepubliquefrance.fr - Le Monde (Luc Vinogradoff), “Sickle Cell Disease: The Great Forgotten of the Health System,” Le Monde, June 16, 2023.

Summary

- A disease born in Africa… to survive malaria

- France and sickle cell disease (between ignorance and neglect)

- Breaking the silence is the first step toward healing

- Healing begins with light

- Main sources