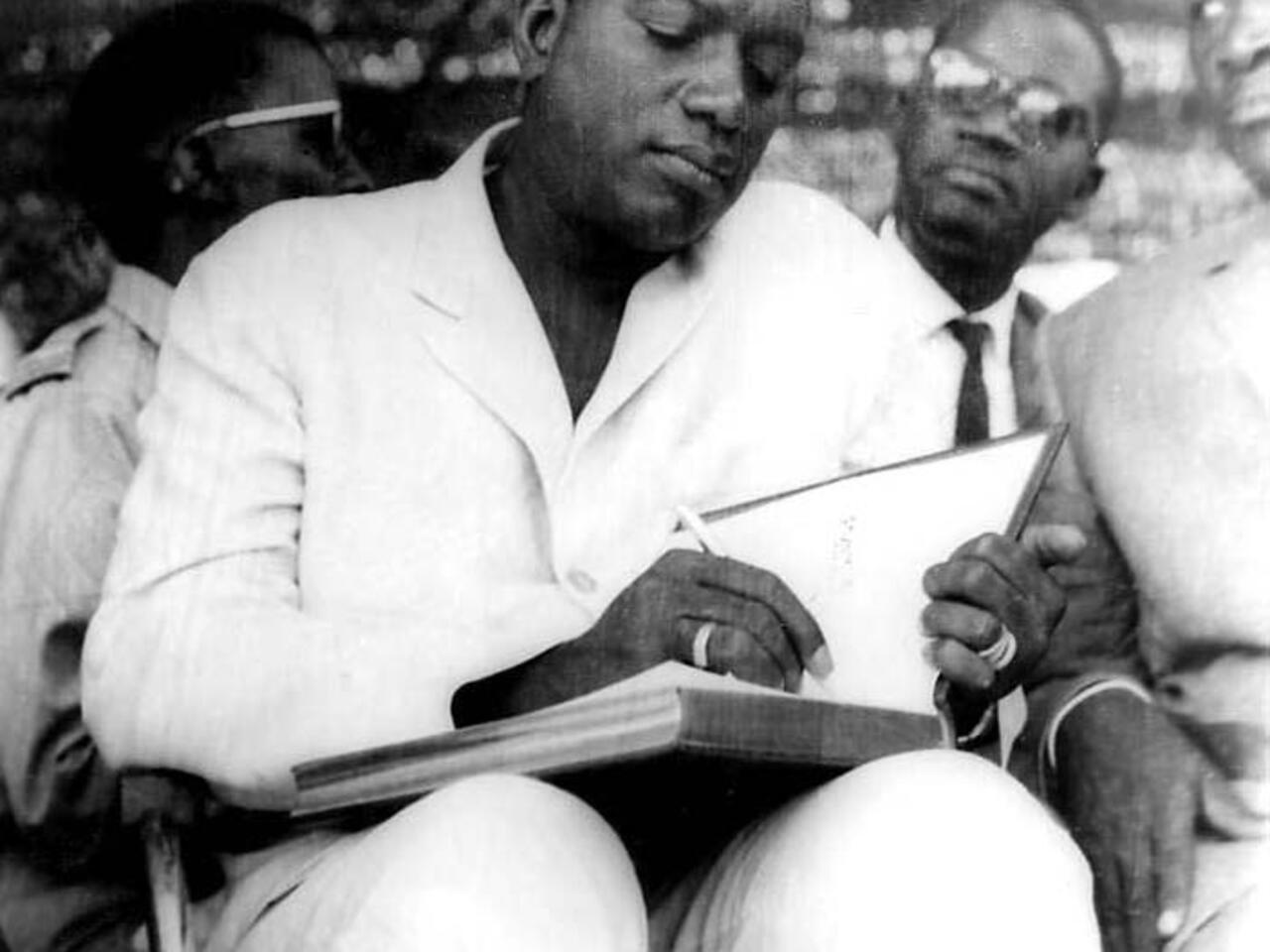

Modibo Keïta, first president of independent Mali, was far more than a head of state: a trained teacher, committed socialist, and uncompromising pan-Africanist, he dreamed of a continent standing tall and in control of its destiny. Yet between red utopia, authoritarian drift, and military betrayal, his journey embodies both the promise and the fracture of postcolonial Africa. Nofi revisits the man, the myth, and the erasure.

Bamako, 1977: The last breath of the founding father

It was stifling that morning in Djikoroni Para. A heavy, humid air hung over the crumbling walls of the paratrooper commando camp, where the very first president of independent Mali had been relegated like a cumbersome relic. In a windowless cell, a 61-year-old man—once hailed as “the guide of the Malian people”—struggled to draw breath. The guards heard no complaints. Truthfully, they had stopped listening long ago.

On May 16, 1977, Modibo Keïta died. Official cause: pulmonary edema. Unofficially (and history has never truly contradicted it): neglect, humiliation, and oblivion. Born a teacher, he became a head of state. Between the two: a continent in flames, a collapsing colonial empire, and a generation of men determined to piece things together their own way.

Mali’s independence, proclaimed in 1960, was a moment of grace. French Sudan became a Republic, colonial flags gave way to green-and-gold hope, and Modibo Keïta carried its breath. He believed, with unshakable conviction, that Africa could stand tall—socialist without Moscow, pan-African without naivety, proud without arrogance.

But utopias are never written without stains. Very quickly, power centralized, dissent fell silent, and the economy faltered. The Malian franc collapsed as a symbol. The state grew rigid, silences became heavier. Modibo, whose voice had once carried a continent’s dreams, became the architect of a closed regime. Eventually, he was overthrown by a lieutenant he himself had promoted and imprisoned in the desert, like a weary oracle.

This account is neither hagiography nor reckoning. It is biographical, certainly, but more importantly critical. It moves between official speeches, frayed archives, tales of old militants, and the awkward silences of a fractured national memory. It interrogates the man, the myth, the failure—and what remains of it. For Modibo Keïta was both the raised fist of a people on the move and the tragic illustration of what happens when a dream collides with the walls of postcolonial reality.

This is not only the story of one man. It is that of a country, a continent, a promise never fully kept.

Child of Sudan, Son of Africa

In the dusty streets of Bamako-Coura, the native neighborhood cast in the shadow of the colonists, a boy was born on June 4, 1915. His name: Modibo. A simple name, almost prophetic in its nobility—for the Malinké, it designates the eldest son, the one meant to lead. His father Daba, a struggling craftsman; his mother, Fatoumata Camara, a woman of quiet dignity, bore him like a hope too heavy for bare hands.

He grew up in French Sudan, tightly controlled by the colonial administration, where every gesture of Black dignity was watched with suspicion. But it was also a land of stories, of living genealogies, of griots carving memory into words. Between bureaucratic beatings and Friday prayers, young Modibo absorbed it all: the language of the master, but also that of the elders.

In 1931, he entered the École Terrasson de Fougères, then in 1934 the famed William-Ponty Teacher Training School in Gorée—a brilliant yet ambivalent factory for shaping indigenous elites. There he met future African leaders. They were taught Descartes, but never Samory Touré. La Fontaine was recited, but not a word on the Kurukan Fuga Charter.

Modibo graduated top of his class, noted for his eloquence and defiance. Colonial teachers already labeled him “a troublemaker to watch.” They weren’t wrong: he would become a teacher, but never one confined to the docile margins of administration. Soon, in classrooms from Sikasso to Timbuktu, he began educating beyond words—awakening consciousness.

But school was not enough. Keïta understood that social transformation also needed culture. He co-founded the “Association of the Literate of Sudan,” which became the “Foyer du Soudan”—a bubbling hub of ideas, political theater, and fiery pamphlets. Through the journal L’Œil de Kénédougou, launched in 1943 with Jean-Marie Koné, he attacked the colonial order head-on, wielding words sharp as machetes.

As early as 1937, with Voltaic ally Ouezzin Coulibaly, he laid the foundations for the first teachers’ union in French West Africa. Pen, speech, classroom—everything was a weapon for Modibo. He hadn’t yet picked up a gun, but his name already circulated in colonial salons like a warning.

In 1946, with war over, winds of change blew. Keïta co-founded the Sudanese Union and immediately joined the African Democratic Rally (RDA), the interterritorial movement led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny. But Keïta dreamed bigger, more radical. Africa shouldn’t merely negotiate its chains—it had to break them.

That same year, he was arrested and briefly interned by French authorities. He emerged more convinced than ever: reforms were illusions; only the colonizer’s departure would restore meaning to African history.

Keïta entered politics not as an ambitious man, but as one in a hurry. In a hurry to birth a new world, even if it meant shaking the old one to its foundations.

Building a nation from the empire’s ashes

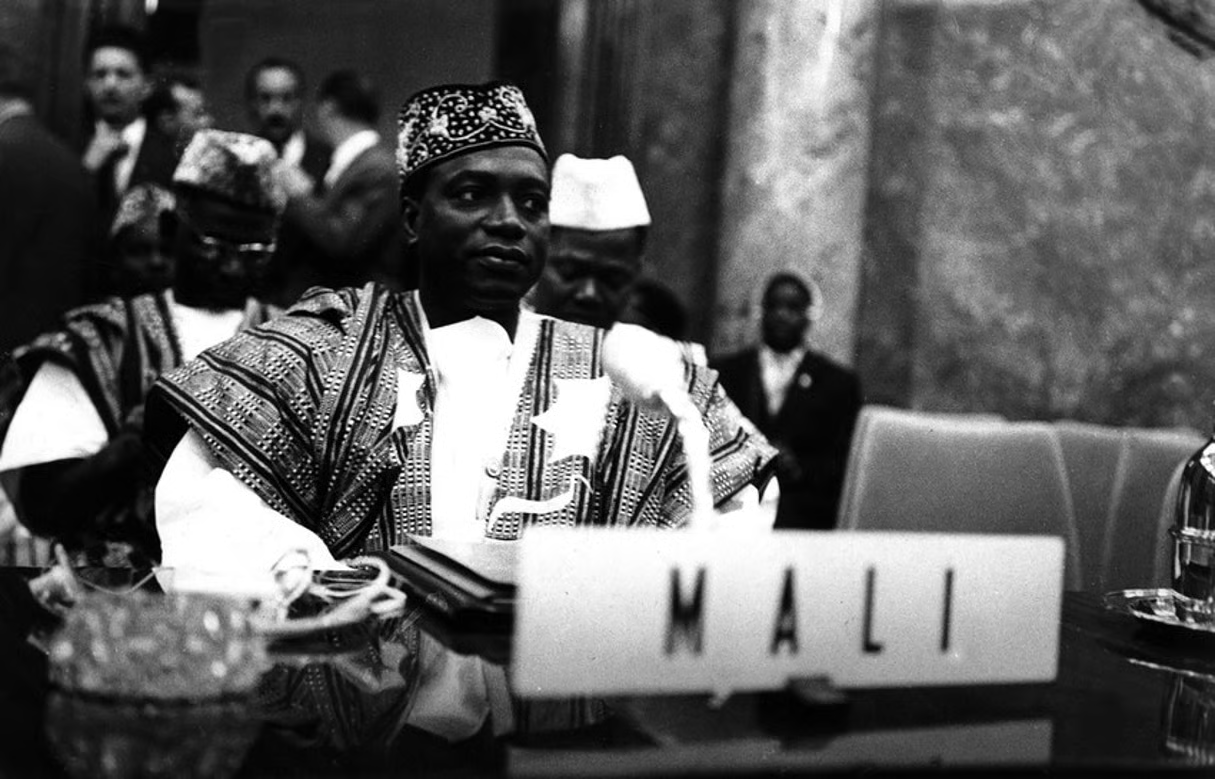

On September 20, 1960, at the Koulouba Palace, the French flags slid slowly down the pole. Two days later, French Sudan officially became the Republic of Mali. Modibo Keïta, in a modest suit and with an intense gaze, proclaimed independence—clearly, unconditionally, without nostalgia.

But in the shadow of this celebration, a silent mourning settled in. Just weeks earlier, the Federation of Mali—a pan-African project he championed alongside Léopold Sédar Senghor—collapsed. Senegal walked away. The dream of a unified West African state was shattered. Deeply wounded, Modibo withdrew further into the conviction that his country must walk alone, no matter the cost.

This rupture marked a turning point. What Modibo couldn’t build with his peers, he sought to create at home—a Mali as a model, a laboratory, a living promise.

He did not hesitate. Mali became a socialist state, modeled on Soviet systems but adapted to African realities—or so the theory went. In October 1960, he created SOMIEX, a state-owned company with a monopoly on imports and exports. Rice, sugar, milk, cotton—everything passed through the state. Even matches.

Then, in 1962, came the Malian franc—a symbol of monetary sovereignty. But reality struck hard: galloping inflation, endless queues, empty shops, thriving smuggling. In Bamako, people whispered the currency was “free but useless.” In the countryside, they returned to bartering.

Discontent grew. Merchants—often branded by the regime as “capitalist parasites”—were watched, sometimes arrested. The state apparatus thickened, surveillance increased. What was meant to be an economy for the people slowly became a machine that crushed the margins.

In 1967, in response to popular weariness and internal criticism, Modibo Keïta launched what he called the “active revolution.” Behind these words: suspension of the Constitution, creation of the National Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (CNDR), and the amplification of a power grown paranoid.

Popular militias, supervised but often overzealous, patrolled the neighborhoods. People were watched, denounced, sometimes beaten. Opponents like Fily Dabo Sissoko or Hammadoun Dicko—once comrades—were silenced, imprisoned without trial. Malian socialism took on the taste of lead.

Yet Modibo remained convinced in his speeches. He spoke of transition, of necessary sacrifice. But the gap between rhetoric and lived experience widened. The state became an ideological fortress, where every critique was viewed as betrayal.

It would be unfair to ignore the quieter, but essential, fronts Modibo tried to open. The fight against the remnants of slavery, particularly in the north, inspired some regime policies. He launched campaigns to free the last captives from traditional chiefs, attempting to dismantle inherited social orders.

But again, his approach was top-down, authoritarian. Old structures resisted—sometimes violently. The struggle for equality clashed with communal realities and silent inertia.

Modibo, the teacher turned president, seemed torn between two logics: that of the benevolent father and that of the inflexible guardian. And between the two, the people suffocated.

Cracks in the dream

There was a time when Modibo Keïta never traveled without an entourage. His speeches were followed by embraces, his journeys punctuated by songs, his pan-African projects co-authored with Nkrumah, Sékou Touré, Ben Bella—even Nehru and Tito. But as years passed, his companions dispersed, alliances weakened, differences widened.

The break with Senghor was brutal, almost personal. Their disagreement over the structure of the Mali Federation was not just about institutions—it was a clash of worldviews. Senghor advocated soft cooperation with France, a polite Francophone Africa. Modibo dreamed of a continent free of all tutelage—even symbolic ones.

In Abidjan, Houphouët-Boigny (another RDA figure) viewed him with growing suspicion. Too red, too radical, too unpredictable. To Paris, Keïta quickly became a “problem,” an obstacle to the postcolonial stability it was desperate to showcase.

He remained loyal to Moscow, but even there, things weren’t easy. Soviet aid was technical, sometimes effective, but never selfless. The USSR wanted a model Mali, not a free Mali.

Gradually, Modibo stood alone—politically, diplomatically, even internally. He still spoke in the name of the people, but the echo was hollow.

On the morning of November 19, 1968, bootsteps echoed through the palace—not those of a foreign army, but of his own officers. The coup was swift, cold, bloodless—but not without violence. It was led by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré, whom Modibo himself had promoted, convinced he embodied a new generation of patriotic soldiers.

A fatal mistake. The power he had forged in the shadow of independence was snatched away without resistance. There would be no debate, no call to the people, no attempt to return. The man who dreamed of building a proud Africa was shipped to Kidal, deep in the desert, far from cameras, far from words.

For nearly nine years, Modibo Keïta vanished—not in death (not yet), but in erasure. No speeches, no photos, no official statements mentioned his name. As if history had chosen to delete him.

In Kidal, he lived in conditions assumed to be degrading: isolation, rationing, constant surveillance. Even the few authorized visitors were forbidden from speaking politics. The Traoré regime, obsessed with its legitimacy, saw Keïta as a living threat—a ghost who might one day reawaken the past.

Then, on May 16, 1977, the news fell—abruptly. Modibo Keïta was dead. The official statement, cold and clinical, referred to him as a “retired teacher”—as if his presidency had never existed. Cause of death: pulmonary edema. But few believed it. Rumors spread: poisoning, neglect, a slow assassination by silence.

His funeral in Hamdallaye erupted into a riot. The people—those he had sometimes frustrated—poured into the streets. To mourn, to shout, maybe to seek forgiveness. Security forces responded with violence. And it was there, in that posthumous tension, that the essence of Modibo Keïta emerged: even in death, he disturbed the order.

Memory of a man, memory of a nation

In 1992, the tide turned. The regime of Moussa Traoré collapsed under the weight of its own authoritarianism and mounting popular resistance. A new political horizon finally opened. Alpha Oumar Konaré, a historian and early activist, became president. One of his first symbolic acts: rehabilitating Modibo Keïta.

It was not merely a political gesture—it was a duty of memory. Keïta’s name returned to public space: schools, avenues, and high schools once again bore the face that had been erased. In 1999, the Modibo Keïta Memorial was inaugurated in Bamako—sober, a bit austere, but necessary.

Yet an official rehabilitation cannot close all wounds. Popular memory remains more ambivalent. For some, Modibo is still the father of the nation, the teacher turned statesman—honest, visionary, incorruptible. For others, he also symbolizes a rigid leader, at times deaf and harsh, who sacrificed freedom on the altar of ideology.

And then there are many who are simply unsure. Younger generations see him on banknotes, in textbooks—but rarely in living conversations. His story is present, but dormant, like something frozen behind glass.

Modibo Keïta never gained the posthumous glory of a Thomas Sankara, nor the global recognition of a Nelson Mandela. He lingers in the blurry zone of pan-African memory, as though his dream had been extinguished too early—too soon compromised.

And yet, his insights still resonate. The idea of an independent African currency—now resurfacing in debates about the CFA franc—was central to his struggle. His vision of a social African state, capable of breaking with neoliberal logic without falling into caricature, remains urgently relevant.

Even his pan-Africanism—so often mocked or betrayed—today regains a certain legitimacy in light of globalization’s disappointments and rising nationalisms.

But one thing is sorely missing: the word. Modibo Keïta spoke. Often. Loudly. With fire. He believed in the power of speech, in the weight of political discourse. It is no coincidence that his speeches were never reissued or translated. The erasure did not stop with his death—it continued, out of neglect, fear, or habit.

One can almost imagine, with a bitter smile, what Modibo would make of contemporary Mali—a country where coups succeed one another like seasons, where the military claims to guard sovereignty, where people still speak of independence… without always knowing from whom they wish to break free.

He might watch, on TV or in the silence of his memorial, this postcolonial ballet where France is denounced even as its structures are replicated. He would see young people shouting “pan-Africanism” in the streets—without always knowing that this word was once his prayer.

Perhaps he would shrug. Or smile, wryly. Perhaps he would remember that a dream can die once, then be reborn—altered, wearied, but still present in people’s hearts.

The dream Is not dead, it sleeps Beneath the Dust

Modibo Keïta was neither a saint nor a tyrant. He was a man—deeply human—with brilliance and blind spots. He sought to forge a proud, just, independent Mali. He fought against colonial inertia, against forgetting, against the impossible. But at times, he also fought his own people—blinded by the urgency to build quickly, to do better than the empire.

What he leaves behind is not a fixed model—it is a call. A call to think Africa with rigor, to believe in words as much as in action. A call to remember that even betrayed utopias often surpass convenient compromises.

Modibo Keïta died in detention. But the idea of a free Mali, of a sovereign Africa, was not buried with him.

Sources

- Francis G. Snyder, The Political Thought of Modibo Keita, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (1967), pp. 79–106.

- Guy Martin, Socialism, Economic Development and Planning in Mali (1960–1968), Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (1976).

- Diarrah Cheick Oumar, Le Mali de Modibo Kéïta, L’Harmattan, 1986.

- Modibo Diagouraga, Modibo Keïta, un destin, L’Harmattan, 2005.

- Daouda Tekete, Modibo Keita, portrait inédit du président, Cauris Livres, 2018.

- Pauline Fougère, État, idéologie et politique culturelle dans le Mali postcolonial (1960–1968), Université de Sherbrooke, 2012.

- Issa Balla Moussa Sangaré, Modibo Keïta, la renaissance malienne, L’Harmattan, 2017.

Summary

- Bamako, 1977: The Last Breath of the Founding Father

- Child of Sudan, Son of Africa

- Building a Nation from the Empire’s Ashes

- Cracks in the Dream

- Memory of a Man, Memory of a Nation

- The Dream Is Not Dead, It Sleeps Beneath the Dust

- Sources