A prominent figure in 18th-century imperial Ethiopia, Empress Mentewab embodies one of the most complex expressions of female power within a sacralized monarchy. At once regent, builder, dynastic strategist, and central actor on the political stage, she asserted herself in a world governed by patriarchal logic without ever denying the spiritual dimension of her mission. Her journey—marked by symbolic triumphs and tragic setbacks—reveals the internal tensions of a transforming empire.

An empress at the heart of a sacred empire

In the 18th century, the Ethiopian Empire, rooted in the highlands of East Africa, was undergoing profound political and social transformation. Heir to a millennia-old monarchical tradition, this Orthodox Christian empire was built upon the sacred legitimacy of the Solomonic dynasty, which claimed direct descent from the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. In this context, imperial power was not limited to political authority: it also represented a spiritual, cultural, and dynastic function essential to the unity of the kingdom.

It is within this imperial framework that the exceptional figure of Mentewab emerges—empress consort to Emperor Bakaffa, influential regent during her son Iyasu II’s reign, and key figure in the destiny of her grandson Iyoas I. Far beyond the roles of wife and mother, Mentewab established herself as a political strategist, a builder of sanctuaries, and a woman of formidable charisma, capable of shaping the very balance of power throughout the kingdom.

How did this empress come to embody, singlehandedly, the tensions and aspirations of a transforming empire? In what ways does her journey reflect the intersecting dynamics of power, religion, and legitimacy in 18th-century Ethiopia?

To answer these questions, we will examine her biography, her central political role, her architectural achievements, and the deep symbolism surrounding her legacy.

From Qwara to the throne

To understand Mentewab’s exceptional stature in Ethiopian history, it is essential to return to her origins and the circumstances that elevated her to the pinnacle of imperial authority. Far from being a mere royal wife, she was first and foremost the product of a powerful noble lineage, bolstered by her evident political acumen from the moment she arrived at court.

Born around 1706 in the province of Qwara, Mentewab (baptized as Walatta Giyorgis) came from a family of the regional aristocracy. Her father, Dejazmatch Manbare of Dembiya, and her mother, Woizero Yenkoy, belonged to lineages close to the imperial power. This noble heritage linked her not only to the kingdom’s elite, but also, according to certain traditions, to an ancient branch of the Solomonic dynasty. Thus, long before becoming empress, Mentewab carried within her a dynastic legitimacy that would strengthen her future political role.

Her marriage to Emperor Bakaffa, on September 6, 1722, marked a decisive turning point. The union occurred under unusual circumstances: Bakaffa’s first wife died mysteriously on the very day of his coronation. This sudden death—an event that, in a court steeped in sacred symbolism, could only be read as a bad omen—paved the way for Mentewab to be called to the imperial throne as the new consort. This marriage was not only a personal alliance; it sealed a political pact between Bakaffa and a regional elite from Qwara, thereby reinforcing the emperor’s political base.

Mentewab quickly asserted herself within the royal circle. Cultured, devout, and skilled in court intrigue, she grasped the mechanisms of power and the stakes of dynastic succession. She gave birth to Iyasu, heir to the throne, thereby consolidating her position. But it was in 1728, when the emperor was struck by a debilitating illness, that Mentewab truly stepped onto the stage as the kingdom’s de facto ruler. Without an official coronation, she became regent in practice, taking control of the administration and palace affairs. This period laid the groundwork for what would become a co-sovereign reign with her son.

Thus, from her earliest years at court, Mentewab distinguished herself through an atypical rise, at the crossroads of familial, political, and religious dynamics. Her authority, far from being accidental, was rooted in a deliberate strategy and a context in which the transmission of power could operate through both masculine and feminine lines.

The shared power

Iyasu II’s accession to the throne in 1730 marked a rupture in Ethiopian monarchical history: for the first time, an empress mother was officially crowned as co-regent. This political gesture, far from being merely symbolic, reflected the reality of power: Mentewab governed the empire alongside her son, who at the time was still a young adolescent. This decision made her not only the guardian of dynastic legitimacy but also the arbiter of political balance at court.

Upon this coronation, Mentewab received the honorary title of Berhan Mogassa (“Light of Grace”), a direct echo of her son’s title Berhan Seged (“Adored Light”). These titles, imbued with profound spiritual meaning, positioned both mother and son not merely as temporal rulers but as quasi-theocratic figures. The fusion of their authority embodied a rare form of monarchic symbiosis, with the throne shared across generations—and genders.

In practice, Mentewab wielded considerable influence over the affairs of the kingdom. All major decisions passed through her. She maintained a close advisory council, negotiated the rivalries among major regional houses, and ensured administrative continuity in an Ethiopia where power was as itinerant as it was fragile. Her Qwaran origins enabled her to rely on a network of supporters in the empire’s northwest, while her status as mother of the emperor rendered her untouchable within the court’s protocol.

Yet such political dominance did not go unchallenged. While her son placed great trust in her, other voices—particularly among rival aristocratic factions—viewed this concentration of power as an anomaly. Although Ethiopian tradition was not hostile to female authority (as seen in past examples of queen mothers or influential wives), it had never formalized such a sovereign power-sharing arrangement. In this respect, Mentewab broke new ground with bold precedent.

Her regency was marked by relative stability but also latent tensions, especially with the growing power of certain Oromo factions within the kingdom. For nearly twenty-five years, she succeeded in maintaining a precarious balance between regions, clans, and traditions. Through constant diplomacy, shrewd marital alliances, and sharp political instinct, Mentewab positioned herself as the linchpin of imperial power during a pivotal era.

However, this exceptional position would soon be called into question after the death of her son Iyasu II in 1755. The arrival of her daughter-in-law Wubit and the enthronement of her grandson Iyoas I would unleash a power struggle that shattered the fragile equilibrium Mentewab had so patiently woven.

Love, lineage, and strategy

While Mentewab is best remembered for her prominent political role, it would be reductive to ignore the more personal (and sometimes controversial) aspects of her life. For the regent was also a woman of passion, whose intimate decisions had far-reaching political consequences. Her life demonstrates how deeply intertwined the personal and political were within 18th-century Ethiopian monarchy.

Shortly after the death of Emperor Bakaffa, Mentewab entered into a relationship with a member of the dynasty: Fitawrari Iyasu, nicknamed Melmal Iyasu—a mocking moniker meaning “Iyasu the Kept Man,” reflecting the perception at court that he lived under the patronage of the regent. This relationship, with a significantly younger man, shocked much of the aristocracy, unaccustomed to seeing a widowed empress break the norms of sacred widowhood, which demanded restraint and seclusion.

But beyond the scandal, this union carried strategic weight. Melmal Iyasu had dual noble descent: paternally from Emperor Fasilides, and maternally from Iyasu the Great (Adyam Seged). In other words, his children with Mentewab were potential heirs with indisputable dynastic legitimacy. The union produced three daughters: Altash, Walatta Israel, and most notably Woizero Aster, who would become the wife of the formidable Ras Mikael Sehul—an unavoidable figure in the succession wars.

Through these alliances, Mentewab extended her influence. She married off her daughters to powerful governors, particularly in the regions of Gojjam, Tigray, and Amhara. In doing so, she transformed her offspring into diplomatic instruments, reinforcing her family’s position in all the kingdom’s key regions. These marriages were not mere aristocratic unions: they were carefully calculated levers to secure loyalty to the central authority she represented.

Yet these personal choices were not without consequence. The imperial court—already fractured along ethnic, cultural, and regional lines—saw Mentewab’s matrimonial strategies as an attempt to monopolize the imperial legacy. When her grandson Iyoas ascended to the throne, open rivalry erupted between Mentewab and her daughter-in-law Wubit, who hailed from the Oromo nobility. This clash was not merely familial: it embodied the growing divide between the Christian highland aristocracy and the increasingly powerful Oromo factions integrated into the state over previous generations.

The episode of her relationship with Melmal Iyasu thus reveals a fundamental trait of Mentewab: her ability to blend emotion, strategy, and dynastic ambition into a seamless exercise of power. In an empire where every birth and marriage could reshape political equilibrium, the empress made her private life a tool of governance—sometimes at the cost of scandal, but always with formidable foresight.

Building for eternity

Beyond politics and court intrigue, Mentewab left an indelible mark on the physical and spiritual landscape of imperial Ethiopia. Like the great patrons of the past, she asserted herself as a builder of empire, erecting monuments that served simultaneously as displays of prestige, acts of faith, and symbols of authority. Through these works, she inscribed her reign into stone, liturgy, and the collective imagination.

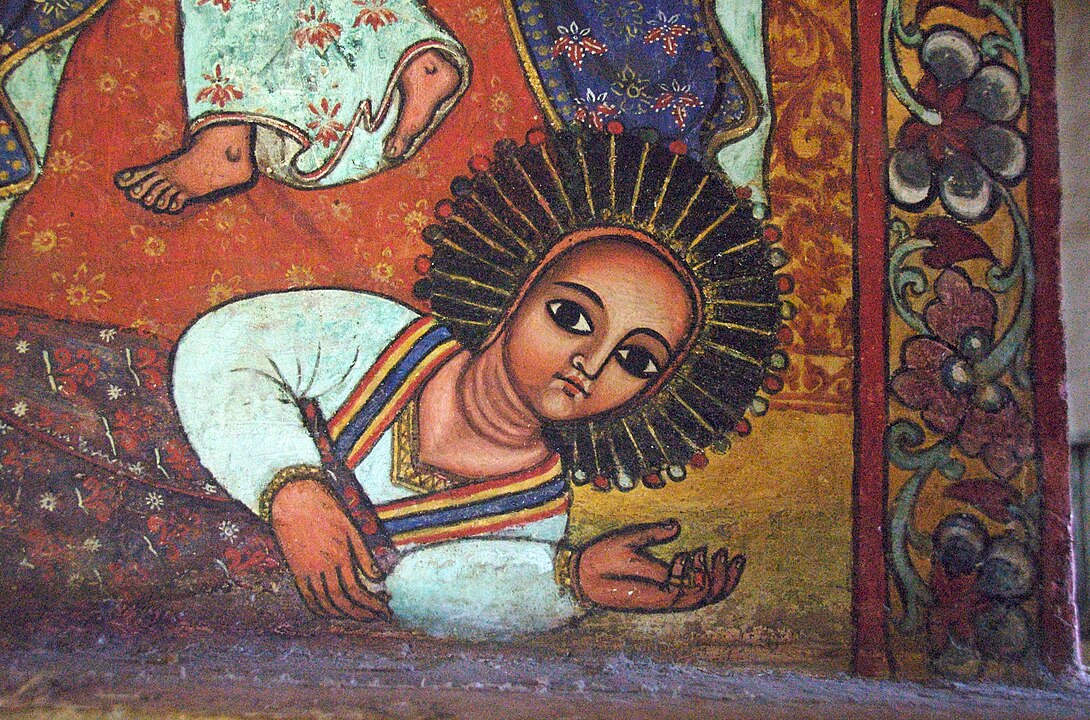

Her most emblematic achievement was undoubtedly the construction of the palace and church of Qusquam, nestled in the wooded highlands near Gondar. This site, named after the place of exile of the Holy Family in Egypt, was no accident: it connected Mentewab to an ancient Christian tradition by placing her sanctuary under the direct protection of the Virgin Mary. Marian devotion—deeply rooted in Ethiopian spirituality—endowed the empress with a sacred aura that complemented her temporal authority.

The Qusquam complex comprised not only a richly decorated church but also a residential palace that became her favored retreat. This dual space—religious and domestic—reflected a coherent vision of female power: contemplative and governing all at once. Far from being merely a place of prayer, Qusquam also served as a center of cultural, intellectual, and political influence. By choosing to settle there at the end of her life, Mentewab made it a site of imperial memory and reflection.

But her architectural legacy did not stop there. In Gondar, the imperial capital, she had her own castle built within the royal enclosure of Fasil Ghebbi, next to those of her predecessors. Through this initiative, she placed herself in the lineage of imperial builder-sovereigns and asserted a female presence in a historically male-dominated space. She also commissioned a monumental banquet hall—an arena for hosting receptions and conducting diplomacy, where the pomp of power unfolded under her direction.

These constructions reflected a vision of power rooted in permanence. Mentewab sought not only to govern but to embed her reign in stone, in ritual, and in posterity. Each building was a message to future generations: the testament of a sovereign who had mastered both spiritual grandeur and temporal authority.

In an Ethiopia where the sacred structured the political, and where sanctuaries competed in magnificence to celebrate the union of God and throne, Mentewab understood that to build was also to reign. Her works marked the apogee of Ethiopian Christian art—nourished by icons, frescoes, and mystical symbols—an art at the service of power, but also of faith.

A Divided court, A fractured empire

Mentewab’s power, which had remained strong for nearly three decades, gradually began to unravel after the death of her son Iyasu II in 1755. With the accession of her grandson Iyoas I—only seven years old at the time—a new dynamic emerged at court: a simmering, then open, confrontation between two women figures—Mentewab, the experienced regent, and Wubit (also known as Welete Bersabe), the mother of the new emperor, from the Oromo nobility.

This conflict—often reduced to a rivalry between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law—was in reality a struggle rooted in deep ethnic, political, and ideological divides. Mentewab, embodying the Christian traditions of the highlands, championed a centralized Solomonic vision of the state. Wubit, by contrast, drew strength from Oromo networks that were increasingly influential in the army and administration and claimed her rightful role as queen mother—much as Mentewab herself had once done.

Faced with this deadlock, Mentewab made a fateful decision: she summoned her relatives and allies from Qwara to Gondar, bringing military forces into the capital to assert her role as guardian of the young emperor. Wubit, for her part, responded by calling in her powerful Oromo kin. The city became a powder keg, teetering on the brink of civil war, with two factions ready for confrontation.

To avoid bloodshed, Mentewab turned to a rising figure from the north—Ras Mikael Sehul, the formidable governor of Tigray and a feared warlord. He agreed to serve as mediator, but Mentewab underestimated his ambitions. Once installed in Gondar, Mikael seized the opportunity to assert himself as the supreme arbiter of power. He sidelined Mentewab, marginalized Wubit, and ultimately had Emperor Iyoas I strangled—a brutal and unprecedented political execution.

This murder plunged Mentewab into profound grief. She, who had dedicated her life to securing her dynasty’s future, saw her grandson betrayed and executed by the very man she had invited to court. Worse still, Mikael Sehul solidified his power by marrying Woizero Aster, Mentewab’s daughter—thus binding his crime to the royal family through a new political alliance.

Broken, Mentewab withdrew permanently from public life. She took refuge in her sanctuary at Qusquam, where she had Iyoas buried beside her son Iyasu II. There, in the solitude of a pious retreat, she spent her final years in silence, immersed in mourning and reflection. She never again set foot in Gondar.

This withdrawal was more than a retreat—it was an act of condemnation, a silent denunciation of a power that had descended into violence. Mentewab, who had skillfully maneuvered through alliances and conflicts, ultimately collided with a harsher reality: the failure of her dynastic strategy, caught between male ambition and ethnic fragmentation. The end of her reign marked the twilight of an imperial golden age, soon to be replaced by an era of turbulence dominated by rival noble houses.

Solitude of a fallen queen

After decades at the heart of imperial power, Mentewab chose to withdraw in a silence heavy with meaning. Her retreat to Qusquam, far from the intrigues of the Gondar court, was not merely a retreat into isolation—it was a form of voluntary exile, a gesture of renunciation, and perhaps also one of disillusionment. In the sanctuary she herself had founded, she lived surrounded by monks, loyal servants, and memories—but deprived of any real influence over the state.

She spent her final years honoring the memory of her deceased loved ones, particularly her son Iyasu II and her grandson Iyoas I, both buried nearby. The triple tomb of Qusquam—uniting mother, son, and grandson—formed a silent pantheon, a poignant testimony to a broken lineage. In this solitude, between prayer and meditation, Mentewab passed away on June 27, 1773, at the age of 66 or 67.

Yet even if her public life ended in seclusion, her legacy did not vanish. Mentewab remains one of the few women in Ethiopian history to have exercised such extensive and sustained power. As regent, strategist, builder, and matriarch, she embodied a rare form of sacralized female authority—still unmatched in the annals of the empire. Through her architectural works, her political decisions, and her dynastic alliances, she shaped 18th-century Ethiopia well beyond her official reign.

Her memory endures in popular and ecclesiastical traditions. The site of Qusquam, with its frescoes, icons, and religious archives, continues to recall the grandeur of a sovereign who was both devout and formidable. Historians remember her as an ambivalent figure: revered for her political vision, yet criticized for her intrigues and failures. Some see her as a tragic queen, a victim of a brutal masculine world; others as a brilliant manipulator, ultimately undone by her own webs of power.

Her name remains tied to the grandeur of Gondar, to sacred architecture, to Marian devotion—but also to the violence of imperial successions and the fragmentation of the kingdom. In this, Mentewab embodies both the apex and the decline of an imperial era in which the throne sought to reflect the divine light on Earth.

Between light and tragedy: The legacy of an extraordinary empress

Mentewab’s story is that of a woman who carved out space for herself in the interstices of imperial power—within a world shaped by men, dynasties, and liturgies. An assertive regent, sacred co-sovereign, mystical builder, and dynastic strategist, she pushed the boundaries traditionally assigned to women within Ethiopia’s imperial hierarchy. Through her journey, she becomes a mirror of the tensions of her time: between tradition and reform, central power and regionalism, the sacred and the political.

She thus represents a rare figure of female power in precolonial Africa, comparable to queens like Nzinga of Ndongo or Amina of Zaria. But whereas these queens led military campaigns, Mentewab wielded a more subtle, embedded, and often indirect form of power—based on diplomacy, imperial motherhood, and the architecture of the sacred. She ruled without a sword, but not without battles: battles against men, against customs, and against the erosion of power.

Her role in sacred architecture—particularly in Gondar and Qusquam—reveals how deeply she understood the role of religious imagination in legitimizing authority. The buildings she left behind are not mere monuments: they are theological and political gestures, declarations of faith as much as affirmations of power.

But she is also a tragic figure. The ambitions she nurtured for her lineage—through her children and grandchildren—were violently dashed. The assassination of her grandson by the man she herself had brought into the court sealed the paradox of her legacy: those she elevated sometimes became the agents of her downfall.

Ultimately, Mentewab is far more than a mere empress consort. She is a cornerstone of 18th-century Ethiopian power, at the intersection of political, religious, and architectural spheres. Through her ability to embody power in multiple forms—visible and invisible, formal and symbolic—she compels us to reconsider the role of women in African monarchies and the complex modalities of precolonial authority.

Mentewab did not merely live through history—she shaped it; and at times, paid the price for doing so.

Sources

- P. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

- D. Levine, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture, University of Chicago Press, 1965.

- R. Pankhurst, “An 18th Century Ethiopian Dynastic Marriage Contract between Empress Mentewwab and Ras Mikael Sehul”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 1979.

- M. Wubneh, Planning for Cities in Crisis: Lessons from Gondar, Ethiopia, Springer Nature, 2023.

- M.J. Friedlander, Ethiopia’s Hidden Treasures, Shama Books, 2007.

Table of contents

- An Empress at the Heart of a Sacred Empire

- From Qwara to the Throne

- The Shared Power

- Love, Lineage, and Strategy

- Building for Eternity

- A Divided Court, A Fractured Empire

- Solitude of a Fallen Queen

- Between Light and Tragedy: The Legacy of an Extraordinary Empress

- Sources