He was a Crow chief, an army scout, a Rocky Mountains explorer — and yet his name has been erased from official accounts. Born into slavery, James Beckwourth became one of the greatest adventurers of the American West. This tribute restores breath and justice to a figure as fascinating as he is forgotten, at the crossroads of Afro-descendant memory and the great open spaces.

Where the legend begins

There they were — five or six, maybe more. Black shadows in the flickering halo of a campfire, lost in the icy vastness of the Rockies. The wind moaned low, long lamentations that seemed to come from afar, as if the mountains themselves remembered.

In the circle, the men were silent. Their faces, weathered by gunpowder, sweat, leather, and solitude, were lit up now and then, revealing scars, watchful eyes, calloused hands clutching pipes or rifle butts. One of them was speaking. Slowly. With that deep voice born of experience or grief — no one could tell anymore. He spoke of another time. Of a man they had once met. Or perhaps it was a tale told by an old Crow guide, somewhere along a mountain pass. The man’s name was James Beckwourth.

Silence fell. A kind of reverence.

That name still echoes — but rarely where it should. It stands on no statue in Washington. It rides in no Hollywood western. And yet Beckwourth was everything America claims to celebrate: a free man, an adventurer, a trailblazer, a survivor. And he was Black. Perhaps that, precisely, is what was never forgiven.

“Those who write history haven’t lived it like we have.” That’s what the old man said by the fire, spitting slowly into the embers. There was no hatred in his voice. Just weariness. The weight of stolen stories.

So that night, in the mountains, between the howls of wolves and the cracking of wood, they decided to tell the tale. Not for the books. Not for the honors. Just so Beckwourth’s name might cross the snow, the wind, the silence.

And live on.

1798–1824: From slaveholding Virginia to the rockies

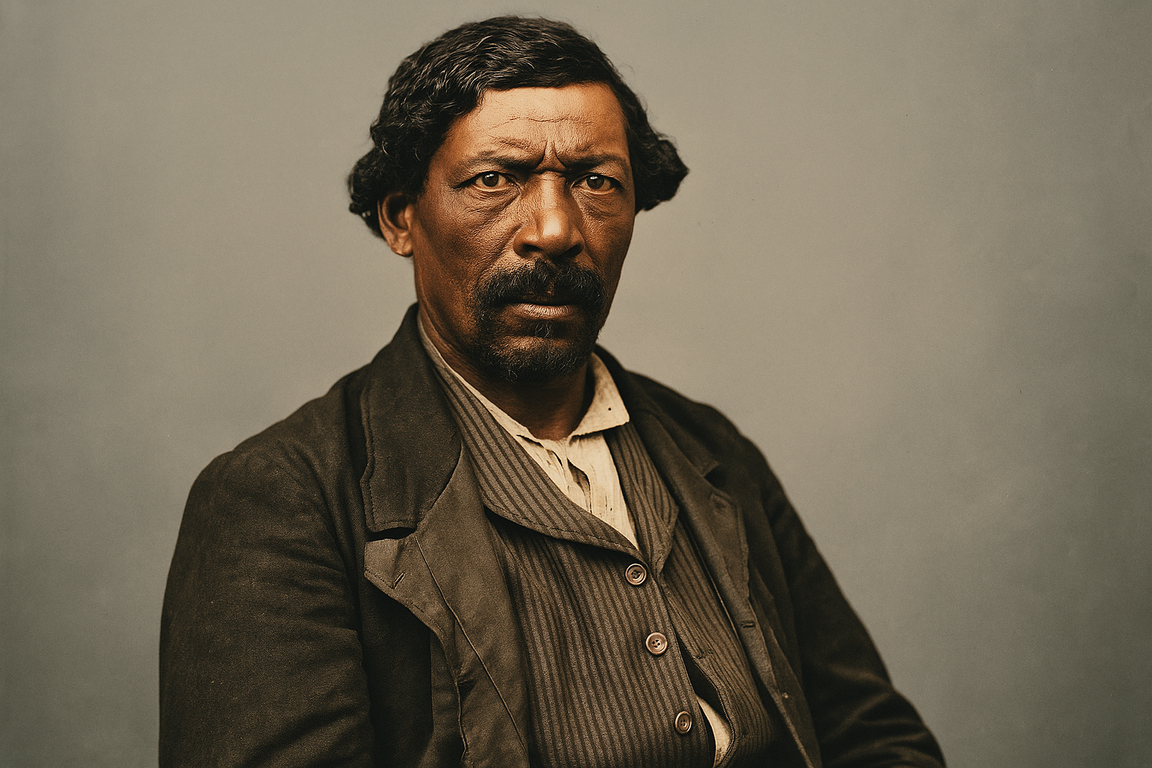

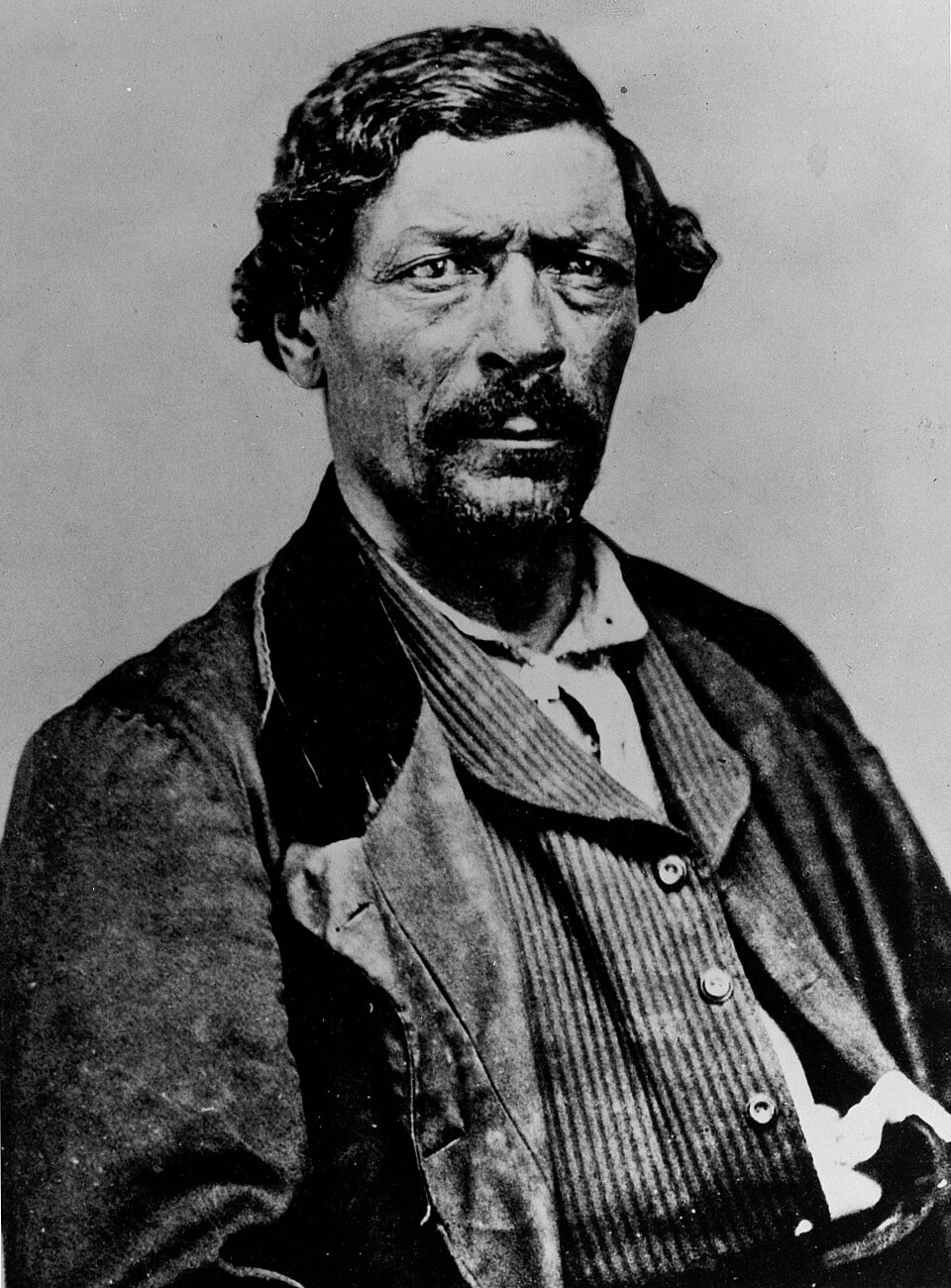

Scanned from: Geoffrey C. Ward, The West: An Illustrated History, Washington, 1996, ISBN 0-316-92236-6.

He was born property. Not a child. Not a citizen. Just a thing — inventoried, exploited, denied. James Beckwourth came into the world somewhere among Virginia’s deep tobacco rows, in April 1798, the illegitimate child of a white master, Jennings Beckwith, and a Black woman reduced to a silent womb. There, already, in the incestuous space of the plantation, the racial fracture carved its paradox: he was both the master’s son and the father’s slave.

Outwardly, young James was “protected”; his father acknowledged his mixed-race children, raised them, taught them to read, even offered them training. But he didn’t free them immediately. Even sons of blood felt the shadow of the whip, because in the South of that time, affection didn’t override skin color. For over two decades, Beckwourth remained legally imprisoned in a system that denied him — until his father finally signed emancipation papers: in 1824, 1825, 1826. Three times. As if freedom had to be insisted upon.

But what is freedom on paper, when other people’s eyes still chain you?

Beckwourth understood early: the East would never be his world. Too many side glances, too many laws written for others. So he left. Westward. Into the unknown. He joined William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company and became a trapper, hunter, muleteer, guide — a “mountain man,” as they were called. Barely twenty-five, already bearing solitude’s wrinkles at the corners of his eyes.

Far from drawing rooms, he learned another kind of warfare. Survival.

Sleeping in the snow. Walking for weeks without seeing a soul. Eating whatever could be found. Watching out for beasts, men, fragile alliances between Indigenous nations and fur companies. Beckwourth became a legend. He knew the rivers, the passes, the languages, the traps. He was clever, tough, fearless.

But he was still Black. And alone.

Among white trappers, he was admired but never embraced. The useful savage, the Black man who knew the Indians, the one sent ahead — but never invited to the evening meal. The frontier — that mythical line of American expansion — became for him a space of emancipation as well as a cruel mirror: you can learn everything, master everything, endure everything… but never truly belong.

So he forged a new identity. In the silence of frost. In the language of the Crows. In the art of retelling his feats around the fire — so no one could ever say he didn’t exist.

1825–1837: Reinvention beyond the white myth

In the vastness of the plains, where the sky spills over the earth without dominating it, James Beckwourth reinvented himself. Far from white codes, legal shackles, and suspicious gazes, he became another man. Or rather, a man — for the first time.

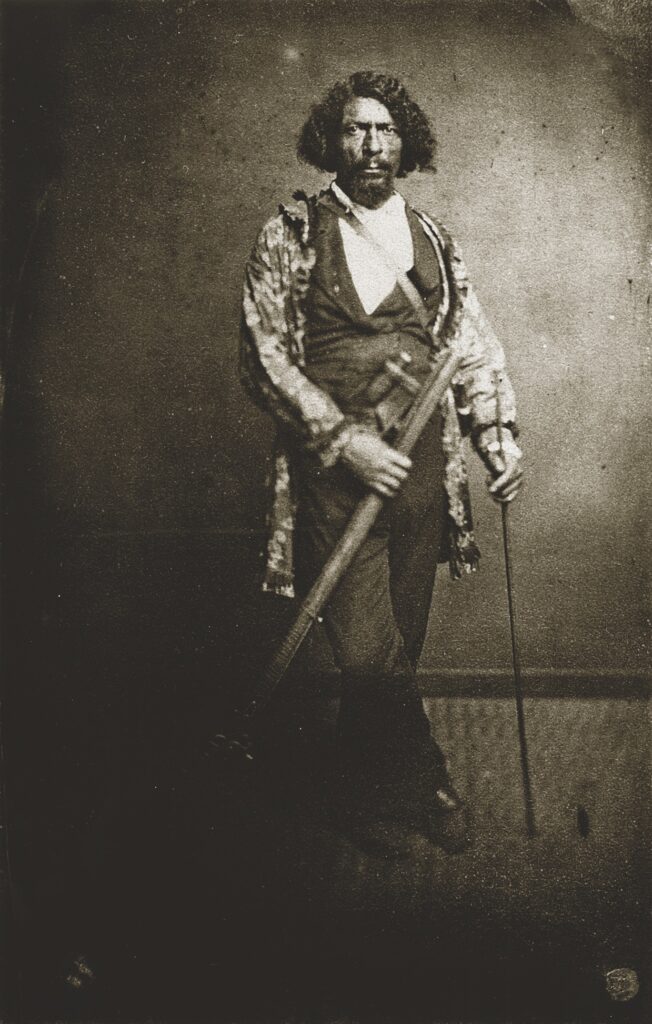

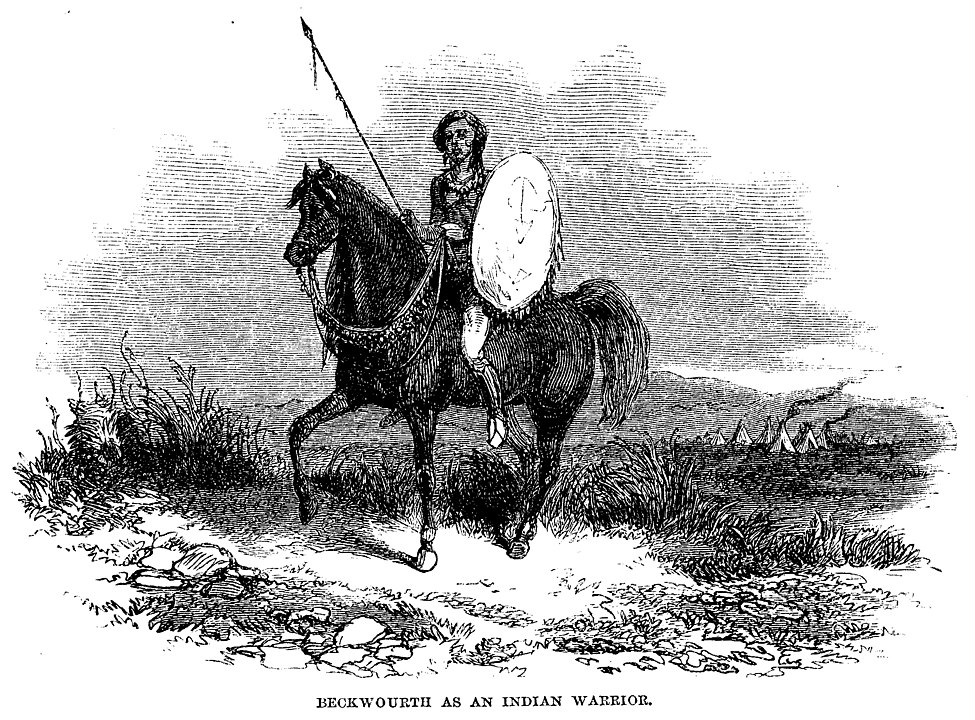

Captured (or welcomed) by the Crow nation, Beckwourth entered a new rhythm of time. Here, a person’s worth wasn’t measured by skin tone but by courage, endurance, and ability to speak to the spirits of the forest. And Beckwourth excelled. He learned the language. Married a Crow woman — perhaps several. He joined raids against hereditary enemies (the Cheyenne, the Blackfeet) and distinguished himself with valor.

Accounts, sometimes embellished by his own hand or that of Thomas D. Bonner, describe him as a war chief, a feared strategist, a buffalo-hide diplomat, able to move between two worlds without betraying his roots. Historical truth merges with oral legend. But that matters little: in Crow memory, Beckwourth is Bull’s Robe, a brother, a pillar. A rare Black figure in Indigenous mythology.

And in that world, he touched something white America had always denied him: legitimacy. Equality. Respect.

But this chapter was not without ambiguity. Beckwourth was not just an “adopted native.” He remained a trapper, a trader, a man tied to powerful fur companies. He sold pelts, did business — sometimes at the expense of those who had embraced him. He was both bridge and fracture, double agent in a world where alliances were fluid, and friendships were traded in powder, salt, and cloth.

And when the time came to leave, he returned to civilization — or its approximation. But he came back changed. Scarred by a life lived between identities: of blood, of culture, of allegiance.

To the white society that never wanted him, he would now respond with stories. And to the Indigenous world that had welcomed him without condition, he offered his loyalty — as long as balance could hold.

In the mirrored rivers of Montana, Beckwourth had glimpsed another version of himself. Wider. Freer. Less confined by boxes.

He was a Black body in a red world. A hyphen between two resistances.

1837–1859: Between wars, conquests, and stolen memory

He returned from the Crow world with warrior instincts and forest memories. But the America he came back to was still one of hierarchy, exclusion, classification. James Beckwourth had lived freely on the ridge line between two civilizations. Now, he had to face History — the kind written without him, despite him.

When he enlisted with the U.S. Army during the Seminole Wars, it was still the frontiersman they sought. But now, there was no question of brotherhood or adoption. He was a guide, a scout, a logistician… a tool among others in a war fueled only by expansionism and treaty-breaking.

Then came the Gold Rush. Thousands of settlers surged into California, pushing violence further west. Beckwourth carved a path: Beckwourth Pass, the lowest crossing of the Sierra Nevada, which he marked, cleared, and left for others. Entire wagon trains poured through this corridor toward the California dream. But Beckwourth, once again, was robbed of credit: Marysville, later ravaged by fires, never honored its debt. Official history forgot his name — like so many others.

In Sacramento, he became a card player, hotel owner, trader. Sometimes hailed as a hero of the West, sometimes dismissed as just another man of color. Ambiguity followed him. White memory viewed him as an anomaly: too Black to be a pioneer, too savage to be a citizen.

So Beckwourth chose to tell his own story. He dictated his memoirs to a traveling judge, Thomas Bonner. The tale was vivid, sometimes implausible, often lyrical. Some called it fraudulent. Others laughed. But behind the flourishes and shortcuts, the book was an act of resistance. A hand extended from the margins toward posterity.

Within its pages, he named the places, the tribes, the men, the dead. He etched his path into America’s terrain. He gave faces to the invisible. He refused erasure.

Because Beckwourth was a ferryman. Not just across mountains or wagon trails —

He was a ferryman of non-white American history. A history where one could be Black, a mountaineer, a husband to an Indigenous woman, a scout, explorer, strategist, survivor.

A history where greatness isn’t measured in statues — but in trails carved through hearts.

1860–1866: The final frontier, between war and oblivion

Source: Miriam Matthews Photograph Collection, UCLA Library Digital Collections.

James Beckwourth’s end was as elusive as his legend — shifting, shadowy, full of whispers. Some say he was poisoned. Some say the Crows betrayed him. Others claim the military, tired of his murky loyalties, sealed his fate. But what’s rarely said is this: Beckwourth died as he lived — on the margins.

In 1864, he collaborated with the U.S. Army during the war against the Cheyenne and Arapaho. He guided the infamous Colonel Chivington’s troops. And during this campaign occurred the horrific Sand Creek Massacre — where over a hundred Native Americans, including women and children, were slaughtered despite promises of safety. The scene was so gruesome that even seasoned frontiersmen turned their gaze. Beckwourth lost more than reputation that day: he lost the respect of those he once called brothers.

The Crows, once his family, shut their doors. He became a pariah — too white for some, too native for others. Always too Black.

He took to the road again, trapping one last time, as if civilization had never truly wanted him. In 1866, he accepted a military mission at Fort C.F. Smith in Crow territory, as part of the buildup to Red Cloud’s War. He suffered headaches, nosebleeds. Whispers claimed he was poisoned by those he had once led and protected. He — child of fire and gunpowder — died alone, far from everything. No drumroll. No remembrance.

His body was buried hastily near Iron Bull’s camp. No stone. No flag. Nothing.

The America of 1866 had neither the time nor desire to mourn a man who blurred the lines between races, nations, castes, and narratives.

But therein lies his greatness.

Beckwourth never had a place — so he made one.

He walked trails others dared not tread. He loved, fought, betrayed, dreamed — always in-between. Always on that fragile line between the world below and the world of the powerful.

He died without official glory.

But he left a trail.

The man of a thousand faces, the history of a thousand silences

Emigrant Trail, Beckwourth Pass, Elevation 5,221 ft.

Lowest pass in the Sierra Nevada, discovered in 1851 by James P. Beckwourth.

Dedicated to the discoverer and the pioneers who traveled this route by Las Plumas Parlor No. 254 N.D.G.W., May 1937.

Neither the desert nor daring Indians could deter them from this western position, and their courage was never shaken as they pressed forward day after day.

— A.W. Wern

Recorded on 8/8/1939

James Beckwourth, the Black trapper who rewrote the West with a scalpel’s edge

Plaque text: Emigrant Trail, Beckwourth Pass, Elevation 5,221 ft.

Lowest pass in the Sierra Nevada, discovered in 1851 by James P. Beckwourth.

Dedicated to the discoverer and pioneers who followed this path by Las Plumas Parlor No. 254 N.D.G.W., May 1937.

Neither the desert nor daring Indians could deter them from this western position, and their courage was never shaken as they pressed forward day by day.

— A.W. Wern

Recorded 8/8/1939

James Beckwourth is a mirage in official histories. A blurred figure, always in motion. Too complex for textbooks, too unclassifiable for statues. He was everything: freed slave, famed trapper, Native war chief, military scout, merchant, writer, living myth.

And to white history, just another inconvenient lie.

His accounts were doubted. His style mocked. He was accused of exaggeration, vanity, fabrication.

But isn’t that always how Black voices are treated when they pick up the pen?

Beckwourth’s autobiography, dictated to a white journalist and published in 1856, is an act of narrative survival. A man refusing to die in silence. A man who, before libraries, before cameras, knew that truth lives in breath, not archives. He told what he saw, lived, endured. Even when it disturbed. Even when it exceeded the frames. Even when it disrupted national myths.

Because what do you do with a Black man who becomes chief among the Crows?

What do you do with a slave’s son who discovers a mountain pass and guides thousands of pioneers to California?

What do you do with a man of the margins who touched everything (including horror) and never let himself be reduced?

America prefers its heroes clean-cut. Not those who muddy the lines between victim and perpetrator, savage and civilized. Beckwourth embodied the ambiguous, the opaque, the uncomfortable. He is living proof that Afro-descendants were not only victims or spectators — but powerful, often unsettling, actors in the conquest of the West.

Even today, few textbooks mention him. Few films tell his story.

But his shadow remains — in every trail across the Rockies.

In every mountain tale where Black voices are silenced.

This isn’t about sanctifying James Beckwourth. He wasn’t a saint.

It’s about restoring him to the epic.

Giving him back his place. His complexity. His flair. His contradictions.

Breaking the silence that entombs him.

Because without him, the story of the American West is incomplete.

And without our memory — so is the future.James Beckwourth, the Black trapper who rewrote the West with a scalpel’s edge

Plaque text: Emigrant Trail, Beckwourth Pass, Elevation 5,221 ft.

Lowest pass in the Sierra Nevada, discovered in 1851 by James P. Beckwourth.

Dedicated to the discoverer and pioneers who followed this path by Las Plumas Parlor No. 254 N.D.G.W., May 1937.

Neither the desert nor daring Indians could deter them from this western position, and their courage was never shaken as they pressed forward day by day.

— A.W. Wern

Recorded 8/8/1939

James Beckwourth is a mirage in official histories. A blurred figure, always in motion. Too complex for textbooks, too unclassifiable for statues. He was everything: freed slave, famed trapper, Native war chief, military scout, merchant, writer, living myth.

And to white history, just another inconvenient lie.

His accounts were doubted. His style mocked. He was accused of exaggeration, vanity, fabrication.

But isn’t that always how Black voices are treated when they pick up the pen?

Beckwourth’s autobiography, dictated to a white journalist and published in 1856, is an act of narrative survival. A man refusing to die in silence. A man who, before libraries, before cameras, knew that truth lives in breath, not archives. He told what he saw, lived, endured. Even when it disturbed. Even when it exceeded the frames. Even when it disrupted national myths.

Because what do you do with a Black man who becomes chief among the Crows?

What do you do with a slave’s son who discovers a mountain pass and guides thousands of pioneers to California?

What do you do with a man of the margins who touched everything (including horror) and never let himself be reduced?

America prefers its heroes clean-cut. Not those who muddy the lines between victim and perpetrator, savage and civilized. Beckwourth embodied the ambiguous, the opaque, the uncomfortable. He is living proof that Afro-descendants were not only victims or spectators — but powerful, often unsettling, actors in the conquest of the West.

Even today, few textbooks mention him. Few films tell his story.

But his shadow remains — in every trail across the Rockies.

In every mountain tale where Black voices are silenced.

This isn’t about sanctifying James Beckwourth. He wasn’t a saint.

It’s about restoring him to the epic.

Giving him back his place. His complexity. His flair. His contradictions.

Breaking the silence that entombs him.

Because without him, the story of the American West is incomplete.

And without our memory — so is the future.

Sources

- Wilson, Elinor, Jim Beckwourth – Black Mountain Man, War Chief of the Crows, University of Oklahoma Press, 1972.

- Beckwourth, James P., The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, dictated to Thomas D. Bonner, Harper & Brothers, 1856.

- Lecompte, Janet, Pueblo, Hardscrabble, Greenhorn, University of Oklahoma Press, 1978.

- Ravage, John W., Black Pioneers: Images of the Black Experience on the North American Frontier, University of Utah Press, 1997.

- DeVoto, Bernard, The Year of Decision: 1846, Little, Brown & Co., 1943.

- Oswald, Delmot R., “James P. Beckwourth” in Trappers of the Far West, edited by Leroy R. Hafen, University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

- Ayres, Thomas, That’s Not in My American History Book, Taylor Trade Publishing, 2000.

Summary

- Where the Legend Begins

- 1798–1824: From Slaveholding Virginia to the Rockies

- 1825–1837: Reinvention Beyond the White Myth

- 1837–1859: Between Wars, Conquests, and Stolen Memory

- 1860–1866: The Final Frontier, Between War and Oblivion

- The Man of a Thousand Faces, the History of a Thousand Silences

- Sources