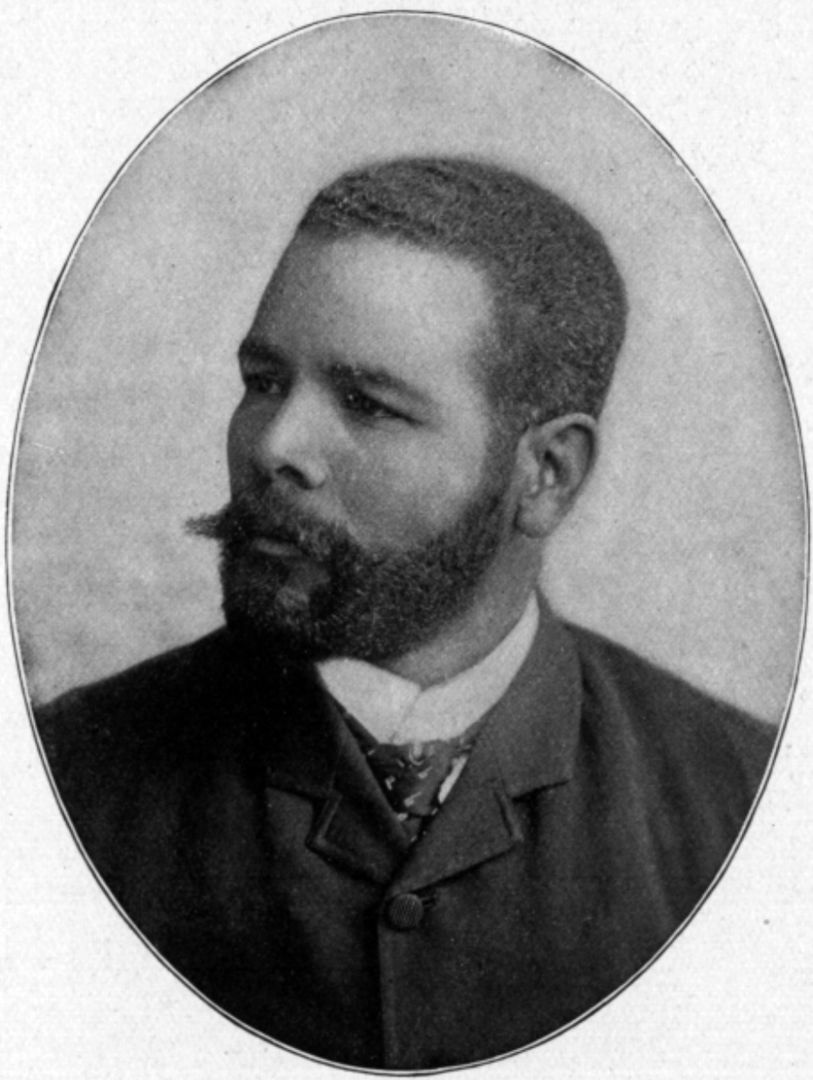

Reduced to a statue in official memory, Antonio Maceo was nonetheless one of the Spanish Empire’s most feared strategists. The son of a freed slave, initiated into Masonic lodges, and a military genius of the wars of independence, Maceo is one of the forgotten figures of the Black Atlantic. Here is the portrait of a man who refused to kneel—even in the face of death.

The silence of statues

Santiago de Cuba. The air is hot, heavy with the salty humidity from the port. Tourists stroll lazily between palm trees, iPhones in hand, searching for the perfect snapshot of this fractured-memory city. On a wide esplanade stands a towering bronze monument: a man on horseback, stern gaze, saber raised to the sky. No one stops. No tour guide, no plaque. The name? Antonio Maceo. One of the greatest strategists of Cuban independence. A general. A free spirit. A Black man.

An old man passes by, straw hat tightly fitted, and mutters as if sharing a secret: “El Titán de Bronce… they don’t want us to remember him.” Then he walks away, carrying with him a piece of history no one seems to want to hear.

Why is Antonio Maceo so little known? How is it that the man the Spanish called el León Mayor is barely mentioned in schoolbooks—even in Cuba? How can a man who led more than 500 battles, wounded 25 times without ever retreating, be relegated to the shadow of a statue ignored by the living?

Because Maceo is unsettling. He unsettles, even a century after his death.

He unsettles because he was Black in a white world. Because he believed that political freedom without racial equality was just a mirage. Because he refused to submit—neither to the Spanish Empire nor to the white intellectuals of the Republic that followed. Because he distrusted the United States even before its marines set foot on Cuban soil.

He unsettles because he wore the machete like a manifesto. Because his thinking, like his skin, was unyielding. Because he knew independence without justice was only a change of flag.

This story is not just about one man. It’s about all the Black figures erased from national narratives, placed in the drawer of silence because they threatened the established order. It is a chapter of the Black Atlantic, a mirror held up to postcolonial memories—a fractured memory we must piece back together.

Restoring Antonio Maceo’s place in history is not about nostalgia. It is about rekindling a spark. A reminder that freedom is never granted. It must be taken. Sometimes at the cost of blood, silence… and forgetfulness.

Mariana, the mother-star

Before the saber, before the revolution, even before the scars on his body and history… there was Mariana. A woman of noble bearing, with a gaze full of infinity. A mother born on the island, but forged in the fire of Caribbean and Dominican heritage. Mariana Grajales Cuello, the source of a struggle that would extend beyond her family to embrace the destiny of a people.

It is often said that Maceo was born a general. But it was Mariana who shaped him—honing his mind through the rigor of uncompromising discipline, teaching him that integrity was not a posture but a form of resistance. In this family, adversity was not avoided. It was stared down.

When war broke out in 1868, Mariana did not tremble. She did not beg her sons to stay. She urged them to go. To take up the machete and join the Mambises—the rebels who refused to bend to Spanish rule. Even more: she went with them. She entered the manigua herself—the rebel forest where the future nation was being forged.

And it wasn’t just Antonio she sent into combat. She sent nine sons. Nine. An entire lineage sacrificed for the ideal of liberty. Because Mariana didn’t believe in freedom granted. She wanted the kind taken with hands stained by soil, sweat, and blood. She dreamed of a republic where Black people walked tall—not relegated to the margins of history.

In her actions, in her silence, Mariana embodied a faith older than any constitution: the belief in justice through dignity. She had no rank, no uniform, no official voice. But her authority was felt. Even generals listened to her. Even Martí, the national poet, called her “the mother of the nation.”

While other figures of independence emerged from salons, Antonio Maceo came from the earth. And that earth had a name: Mariana. She was the one who initiated him into free thought, self-respect, and Black pride as a foundation for political engagement. By infusing him with the blood of rebellion, she turned her son into a legend.

But legends come at a price.

And his would be paid in the jungles, in makeshift hospitals, in bullets tearing through flesh. For behind every hero, there is a mother whose tears will never fall in public.

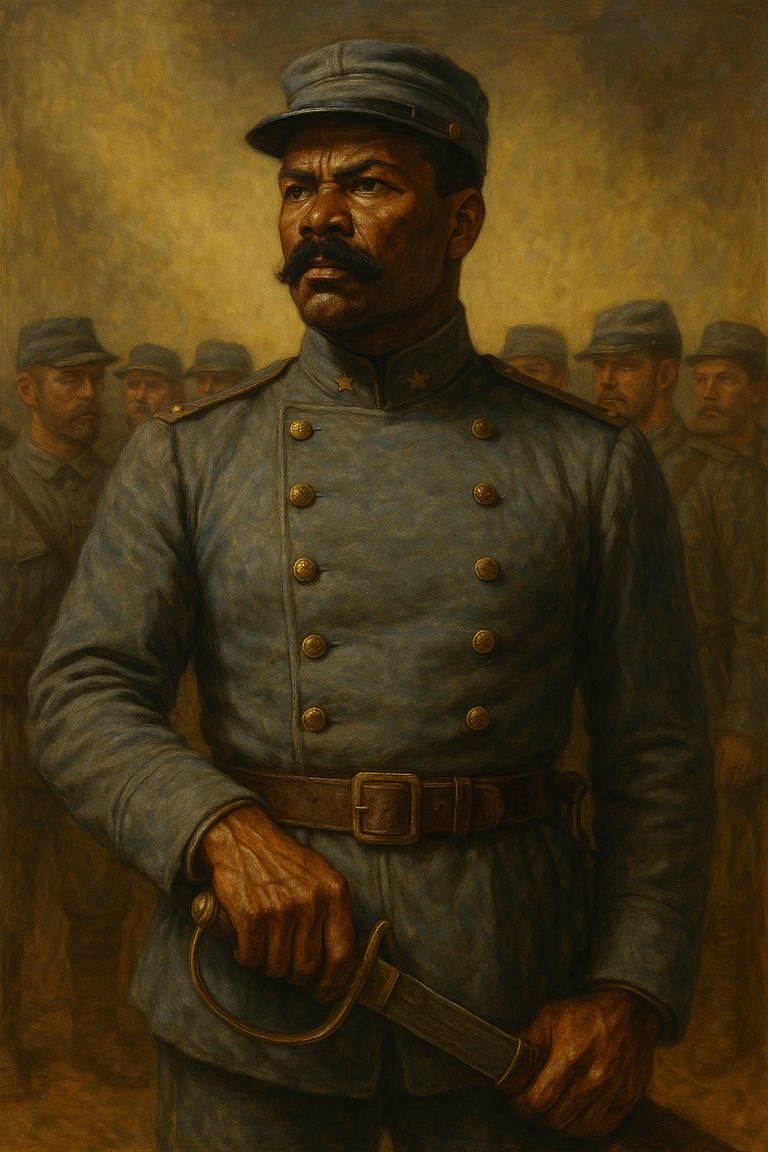

A Black General in an army of prejudices

It was a war for liberation—but not yet a war for equality.

When a young Antonio Maceo took up arms in 1868, he dreamed not only of independence. He dreamed of a country where a Black man could command without apologizing for his skin. But within the rebel army, he quickly discovered another enemy: the prejudice lurking among those who shouted “freedom.”

In that army of patriots, skin color did not vanish under the uniform. Maceo climbed the ranks by the edge of his machete—but every promotion was a battle. Despite his military feats, despite his victories, he saw less experienced white men placed above him. He was tolerated, but feared. His tactical brilliance disturbed them—his Blackness disturbed them more.

And yet he advanced. Tirelessly. Defiantly. Determined to write his name in history not as an executor, but as a thinker. He led over 500 battles. Sustained more than 25 wounds. Each scar on his body was a silent answer to those who doubted him. And his soldiers—mostly Black—followed him without hesitation. Because they saw in him something the elites refused to see: a leader born of the people, forged in pain.

They called him El Titán de Bronce—the Bronze Titan. The name said it all: brute strength, tenacity, Black pride. But it also spoke to the constant effort to prove himself. As if, to be recognized as a general, Maceo had to be superhuman.

Let’s be clear: Antonio Maceo was not just a war hero. He was a living challenge to racial hierarchy. A counter-narrative. An affront to the official story of a white nation pretending to be rebellious while maintaining exclusion.

And perhaps that is why he would never fully enter the sanitized pantheon of consensual figures. Because he pressed on the raw nerve: the contradictions of a revolution that cried “freedom,” but whispered “not for all.”

The shadow of Zanjón

February 10, 1878. At Zanjón, the sabers are lowered. The silence of arms marks the official end of the war. After ten years of struggle, Cuban revolutionaries agree to a compromise with the Spanish Crown. An amnesty is granted. But freedom? The abolition of slavery? Independence? Nothing.

That day, many sign. Antonio Maceo stands up.

Where others see exhaustion and a chance for respite, Maceo sees betrayal. He cannot understand how anyone can speak of peace without emancipation. He refuses to erase ten years of bloodshed for the sake of an empty agreement.

He demands a meeting with the Spanish captain general, Arsenio Martínez Campos. They meet in Baraguá, deep in the bush, beneath a heavy sky. The Spaniard speaks of peace. Maceo speaks of principles. “We do not want a peace without independence, nor without the end of slavery,” he declares. The general, stunned, takes note. The silence is tense. The scene enters history: the Protest of Baraguá.

But official history prefers signatures over insubordination.

Maceo gains nothing that day. He returns to arms, almost alone. He is hunted down and forced into exile—first in Jamaica, then in Costa Rica—living in semi-clandestinity. Far from the homeland, but never from the struggle. He becomes a living legend. And that legend, paradoxically, is uncomfortable.

Because Maceo reminds all who accepted Zanjón of a painful truth: they gave up too soon.

By refusing to compromise, Maceo etched into Cuban memory a rare act: that of a man who says no, even when it means losing, isolating himself, disappearing. That “no” carries more weight than any medal. It marks the fracture between two visions of liberty: the one you negotiate, and the one you seize.

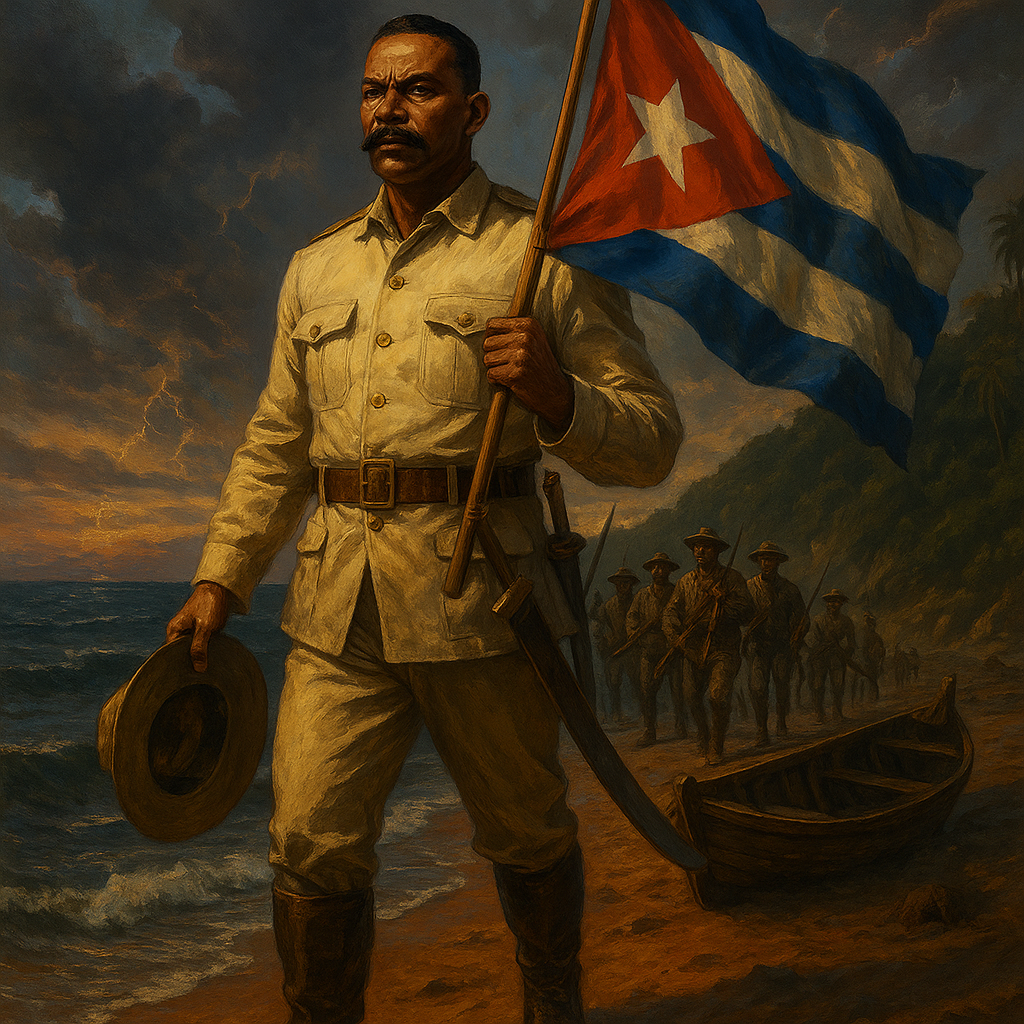

The titan’s return

1895. Seventeen years after rejecting the peace of Zanjón, Antonio Maceo boards a small boat bound for Cuba’s eastern coast. The sea is rough, the air electric. He is no longer the flamboyant young general. He is 50 years old. But the fire in him hasn’t faded. He has returned to finish what he began.

At his side: Flor Crombet, a few armed men, scant supplies. The expedition seems suicidal. Yet, upon landing in Baracoa, Maceo finds the manigua again—the forest, the caves, the secret guerrilla paths. The people had been waiting for him. The “Titán de Bronce” is not an exile returned from the dead: he is a resurrected promise.

The Spaniards thought he was finished. They find instead a renewed force. Now lieutenant general of the independence army, Maceo resumes the war where he left off. But this time, he’s learned. He distrusts internal divisions. He negotiates with Martí, with Gómez. He demands unified military leadership—and gets it.

Then begins the great march across the island. In three months, Maceo and his troops cross Cuba from east to west—over 1,000 kilometers on horseback, on foot, bleeding. They face jungle, mud, fevers, Mauser rifles. They break through Spanish lines, barbed wire fences, fortified posts.

Every village becomes a stronghold. Every victory a slap in the face to colonialism.

Never in Cuban history had a Black general dared go so far, with such mastery, endurance, precision. Maceo is not just a strategist; he is a body turned cause. He moves as if knowing every step would one day be carved into popular memory.

But this campaign, however heroic, is also his swan song.

For Maceo is unsettling—even among allies. Too Black, too popular, too unyielding. He embodies a revolution that doesn’t stop at political independence but demands racial justice. And in a society still steeped in prejudice, that is too much.

His return is triumphant, but his future darkens. And Maceo knows it. He writes to loved ones that he does not fear death—but fears that his sacrifice will be co-opted, distorted, erased. He fears history will turn him into a mute statue, a polished figure.

And it is on that westward path, the one he treads with pride, that death will come for him.

The ambush at San Pedro

December 1896. War rages in western Cuba. Antonio Maceo moves through tobacco and sugar plantations, in the countryside where he once triumphed. He is no longer invincible, but still feared. The Spaniards know that to crush the revolution, they must strike at its heart: Maceo.

On December 7, on the edge of Punta Brava, at a property called San Pedro, he advances with his doctor and about twenty men. It is not a battle. Not even a standard ambush. It is a trap—a political assassination disguised as combat.

A traitor has sold their location. Gunfire erupts. Maceo, massive, on horseback, tries to retreat. But two bullets bring him down. One pierces his chest. The other shatters his jaw and enters his skull. The Bronze Titan collapses. Beside him, only one man remains: Panchito Gómez Toro, the young son of General Máximo Gómez. He refuses to flee. He throws himself on his mentor’s body. He is slaughtered.

The shock is immense. The silence, total.

At first, the Spaniards do not realize whom they’ve killed. Only later, when searching the bodies, do they understand. But what they don’t know is that the blood spilled at San Pedro will nourish the popular memory.

His body, initially abandoned, is secretly recovered. Two Creole brothers hide it and swear to reveal the grave only upon liberation. For years, Cubans will pay tribute to his unburied ghost, in a whisper of resistance.

But more disturbing than his death is its meaning. Because Maceo, more than a general, carried a vision: a Cuba not only free—but just. An island where Black people would no longer be cannon fodder for the revolution, but its architects.

His death is not just that of a soldier. It is an attempt to neutralize a radical imagination, a defiant hope. And it is no accident that for decades, official history froze him in bronze: silent, glorified—but disarmed.

Stolen legacy, contested memory

Today, Antonio Maceo’s statues still raise their fists in Cuba’s public squares—in Santiago, Havana, Baraguá. Monumental, always on horseback, gaze fixed forward. But how much do we really know about the man behind the icon?

Maceo is commemorated but little understood. Honored but rarely taught. In history books, his name appears, boxed in by dates and battles—but his fight for racial justice, his rejection of colonial compromises, his opposition to American imperialism… all that remains in the margins.

Because Maceo still unsettles.

He unsettles the Spanish, of course, for humiliating their military for nearly thirty years. He unsettles some Cuban elites, for having demanded real equality for Afro-descendants—not just their presence in the trenches. He unsettles the United States, for Maceo wanted neither their tutelage nor their military aid, anticipating the creeping annexation that would follow the Mambises’ victory.

His political testament is radical: freedom, yes—but not without dignity.

He died refusing to be used, forgotten, or tamed. And for that, official history tried to silence him another way: by turning him into a myth. He is praised for bravery, but his strategic genius is downplayed. His physical strength is celebrated, but his overt Black anticolonialism is erased. He is shown as a national hero—but mention of his skin color as political identity is avoided.

But in the diaspora, something remains alive.

In Haiti, Jamaica, New York, Paris—the descendants of the great Atlantic insurrection see in Maceo a comrade-in-arms to Toussaint Louverture, Samory Touré, Zumbi dos Palmares. A Black man who refused white domination in all its forms—Spanish or American. A man who knew how to say no when others chose to survive.

Maceo did not die at San Pedro.

He lives in every act of resistance, in every struggle for justice, in every call for diasporic unity. He is the whisper echoing through the centuries, reminding us that freedom is not a concession—it is seized or it is betrayed.

Sources

Aline Helg, Our Rightful Share: The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886–1912, University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Rebecca J. Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery, Harvard University Press, 2005.

Peter Wade, Race and Ethnicity in Latin America, Pluto Press, 1997.

Norma E. Whitten & Arlene Torres, Blackness in Latin America and the Caribbean, Indiana University Press, 1998.

Portal to Texas History, History of Negro Soldiers in the Spanish–American War (1899).

Table of Contents

– The Silence of Statues

– Mariana, the Mother-Star

– A Black General in an Army of Prejudices

– The Shadow of Zanjón

– The Titan’s Return

– The Ambush at San Pedro

– Stolen Legacy, Contested Memory

– Sources