As African independences are being commemorated, one name remains strangely absent from official narratives: that of the Cameroon War. Between 1955 and 1971, a brutal guerrilla conflict pitted the nationalists of the UPC against French forces and their local allies. Mass arrests, torture, villages razed, forbidden zones: this conflict—often labeled the “invisible war”—was one of the cruellest of the post-colonial era. Here is its history, caught between suppressed memory and historical truth.

The war that France wanted to erase: Understanding the Cameroon war (1955–1971)

“That night, they surrounded the village in silence. Not a dog barked. The rifles began talking before the rooster even crowed. I survived because I was hidden under the floorboards, with my little brother. But when I came out… the village no longer existed.”

– Testimony of André B., former UPC guerrilla, recorded in Bafoussam in 2009.

There are wars without names. Conflicts never declared, never recognized, never even taught. Confrontations as bloody as they are erased. The Cameroon War is one of them. Between 1955 and 1971, a ruthless guerrilla struggle pitted the Union of the Populations of Cameroon (UPC)—a pan-African independence movement—against first the French colonial administration, then the Paris-backed Cameroonian government. For nearly two decades, France waged one of its longest colonial wars… while refusing to acknowledge it as such.

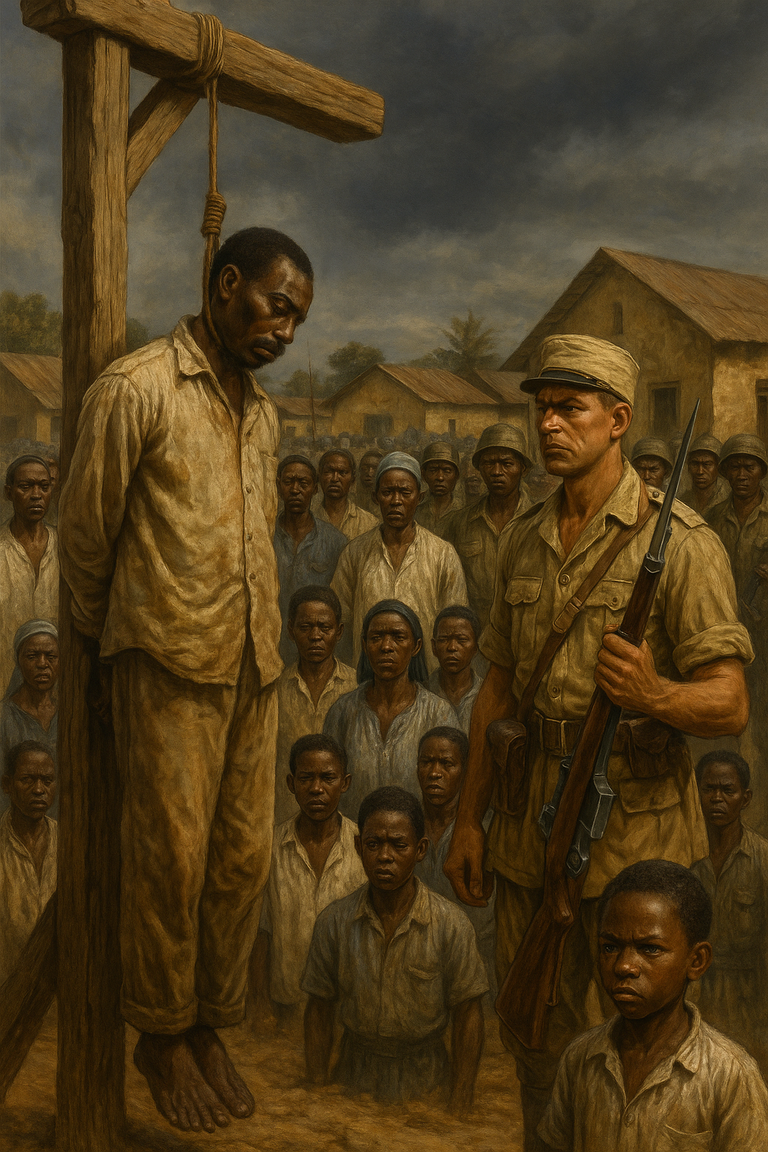

We speak here of villages razed with napalm, entire zones declared “off-limits,” cordoned off and bombarded; thousands of political prisoners executed without trial; nationalist leaders poisoned, shot, buried anonymously in Central African forests. A war whose official archives were long sealed, whose witnesses were silenced, whose survivors were forced into hiding.

In French and Cameroonian schoolbooks, this period remains hazy, reduced to a few lines, a few vague phrases. It’s called “unrest,” “rebellion,” “pacification.” Rarely “war.” Never “occupation.” Almost never “responsibility.”

Yet this war was a foundational clash between two worldviews: on one side, a declining empire clinging to its former colonies through compliant local elites; on the other, men and women dreaming of a genuine, popular, radical independence—an independence that can’t be negotiated, but must be fought for.

Understanding the Cameroon War is therefore more than historical research: it’s an act of memory, justice, and reparation. It is dismantling the myth of a “peaceful” decolonization in Francophone Africa. It is restoring to the narrative those whom official history deliberately erased.

Colonialism, the UPC and the thirst for independence (1922–1955)

To understand the Cameroon War, one must go back to a central historical lie: that this country was never a colony like any other. In 1919, after Germany’s defeat in World War I, Cameroon was placed under French and British League of Nations mandates. Those mandates were ostensibly meant to prepare the population for autonomy—but in reality, they reproduced and intensified colonial domination.

Under French mandate, Cameroon became a colonial laboratory: large infrastructure projects, export crops, commercial monopolies…and systematic exploitation of resources and human bodies. The indigénat legal code was applied with brutality: forced labor, crushing taxes, mass population displacements, racial segregation. Symbolic violence accompanied this: the outright denial of any political or intellectual capacity among Africans.

But times changed. In 1945, World War II shook imperial arrogance. African soldiers fought—and died—for Free France. Indian independence in 1947, North African nationalist movements, the founding of the UN… a new wind seemed to blow across empires.

In that context, the Union of the Populations of Cameroon (UPC) emerged in 1948. Led by an educated, militant, pan-African generation—Ruben Um Nyobè, Félix Moumié, Ernest Ouandié, Marthe Moumié, Ossendé Afana—the UPC rejected half-measures. Its slogans were clear: immediate independence, reunification of Eastern and Western Cameroon, popular sovereignty, fight against colonial corruption.

The UPC didn’t just speak—they built: schools, clinics, peaceful demonstrations, cooperatives. They reached both rural and urban masses, becoming the beacon of hope for real independence—much to the alarm of French authorities, who labeled them “subversive.”

By 1953, the noose tightened: activists surveilled, meetings banned, newspapers censored. In May 1955, under the pretext of “public order disturbances,” the French government banned the UPC. Its leaders went underground. Guerrilla units began organizing. A war was germinating—and it was France, once again, that chose repression over negotiation.

1955: War breaks out, but we don’t call it war

On 25 May 1955, a decree from Paris dissolved the UPC. With a few lines, the colonial state wiped the main Cameroonian independence movement off the map. From that day on, the UPC was no longer a political party—it was a “subversive organization” to be neutralized.

The tinder had been lit—and it ignited. Within days, uprisings erupted in Douala, Nkongsamba, Édéa, Yaoundé: demonstrators carried signs reading “No to enslavement!” and “Immediate independence!” Police stations were stormed, buildings torched—and France’s response was lethal: live ammunition was fired2.

But the insurgents persisted. In the Bassa and Bamiléké regions, militants went underground, forming cells in forests, hills, and working-class neighborhoods. This was the beginning of a guerrilla war that the French state refused to acknowledge. To admit “war” was to admit that Cameroon was occupied and its people had a right to liberation.

So, the lie began: in Paris, authorities spoke of “sporadic unrest,” ministers downplayed the crisis, the press—muzzled—drew the conflict as a “rise in banditry.” Meanwhile, the colonial high command quietly deployed massive military logistics: troop reinforcements, air support, armor, counter-insurgency tactics. The war was real—but mired in secrecy.

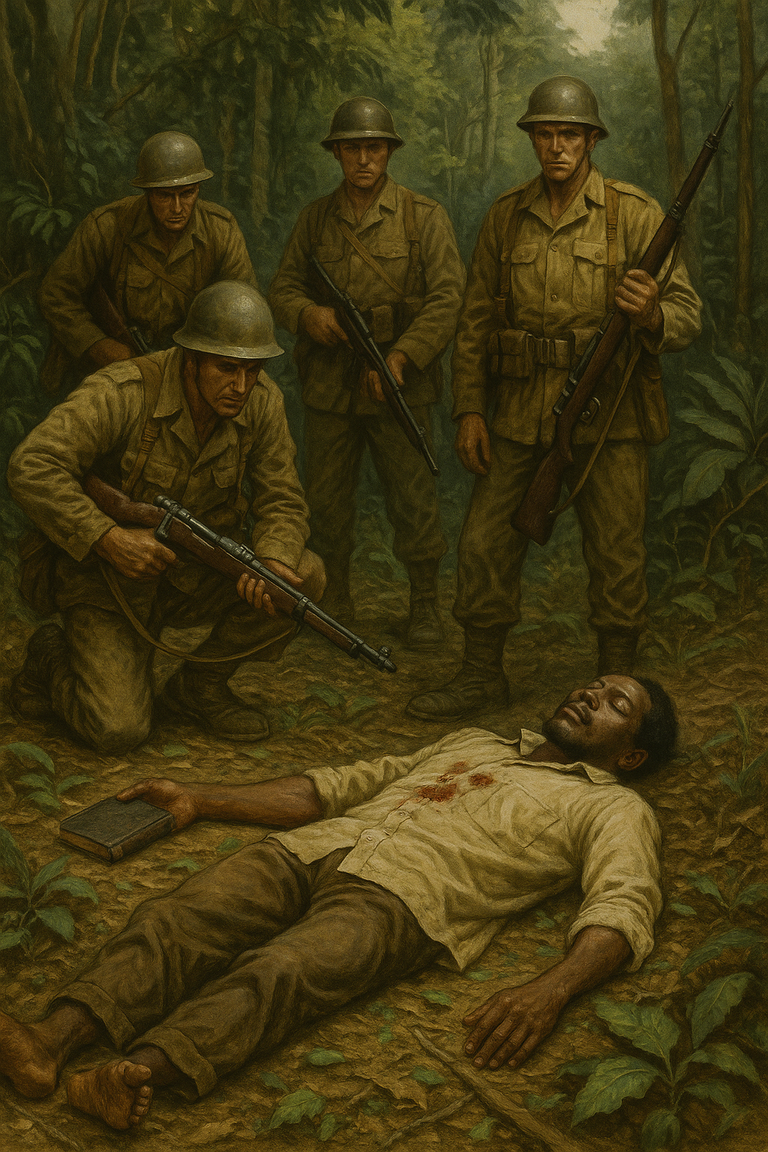

Entire villages were surrounded, bombed, and burned. Women, children, the elderly were not spared. In Nkondjock, Boumnyébel, Bafang, troops razed hamlets, raped, tortured, executed. Napalm was used. Detention camps were set up in the northern savannas. Death followed in silence.

Administrative language served as a smoke screen: the dead were just “hostile elements neutralized,” the guerrillas “outlaws.” Bombed villages? “Terrorist hideouts.”

Terms like “law enforcement,” “pacification,” “clean-up operations” were euphemisms for war crimes.

Yet the Cameroonian people understood the reality: this was no ordinary campaign for independence—it was a war of liberation against an empire willing to sacrifice everything to keep its last strongholds.

A hidden war: Espionage, torture, counter-insurgency

Cameroon’s war wasn’t just fought in forests or villages. It was waged in the shadows—inside barrack cellars, soundproof prison cells, opaque telegrams. With no official acknowledgement, France conducted a parallel war without witnesses or limits: a shadow war.

By 1957, French intelligence (SDECE) took control. They planted agents across Douala, Yaoundé, Nkongsamba—penetrating unions, churches, villages. UPC militants were tracked, listed, entrapped, sometimes killed. Denunciation became a political tool; fear was weaponized.

The French army applied a doctrine honed in Indochina, refined in Algeria—a counter-insurgency war3 targeting not just fighters but whole social environments: peasants, women, intellectuals, griots, teachers, traders. UPC had to be eradicated—even in minds and spirits.

“A good guerrilla is a dead guerrilla, and their silence is more useful than their screams.”

– From a classified French military report, 1959.

In prisons in Yaoundé, Bafoussam, Douala, survivors spoke of the unspeakable: prisoners electrocuted, hung by their feet, forced to dig their own graves; women raped publicly to break guerrilla morale. French military doctors like Pierre Messmer and officers like Commander Aussarresses were never held accountable; many later ascended into politics.

To cover up atrocities, populations were moved and “strategic villages” built to isolate UPC supporters—part of a system of surveillance, psychological control, social suffocation.

Most importantly, everything was denied. France—a country of human rights—has never recognized that torture was used in Cameroon. No official commission. No trials. No compensation.

Yet the traces remain—in declassified archives, in survivors’ testimonies, in the landscape: some rural areas still referred to as “the red lands,” stained with blood and laterite.

The assassination of Um Nyobè: When a man becomes a state targetat

He walked barefoot, carried a Bible and notebook. He spoke Bassa with farmers, French with missionaries, English with UN delegates. Ruben Um Nyobè, the “Mpodol” (“the one who bears the Word”), was more than a political leader—he was the voice of a free, pan-African, dignified Cameroon.

In internal exile since 1955, hunted since the UPC’s ban, Um Nyobè never picked up arms. He believed in the power of speech, intellectual resistance, popular mobilization. Between 1952 and 1955, he submitted numerous memoranda to the UN, denouncing French abuses, democratic denial, and colonial violence in Cameroon. In New York, he thundered:

“Colonization is an enterprise of pillage, hatred and humiliation.”

These speeches unsettled France, provoked alarm and international solidarity. In colonial police dossiers, Um Nyobè was designated “to be neutralized by any means.”

On 13 September 1958, in the Boumnyébel forest, he was located. The French army surrounded his group and opened fire. Nyobè died riddled with bullets—no trial, no warrant, no witness. His body lay unburied for days, banned from religious or public burial.

“Bury him like a dog.”

– Order reportedly given by a French officer, according to local testimony.

But the Mpodol’s words survived. In villages, his speeches were whispered, his writings circulated. His assassination marked a turning point: France, which claimed to guide nations to freedom, showed instead that it preferred to kill leaders rather than dialogue.

This state crime remains unacknowledged to this day—no judicial inquiry, no trial, neither in France nor in Cameroon4.

Bamiléké: The population targeted by a “Dirty War”

If one were to map the horror of the Cameroon War, the Bamiléké region would be marked in blood. From Bafoussam to Dschang, Bangangté to Mbouda, the hills still echo with gunfire, the screams of the suffering, the silence of mass graves. This was where the war was most feral—and most concealed.

From 1959, UPC guerrilla units reorganized in the West. But French repression quickly took an ethnic turn. The Bamiléké—suspected of aiding the guerrillas—became collective targets. The colonial army, followed by the post-independence Cameroonian military, carried out what amounted to ethno-political purge5.

Villages were surrounded and set aflame. Residents—women, children, elders—rounded up and shot en masse. Bodies were dumped into wells, pits, ravines.

- In Bayangam: reportedly over 400 people killed in one night.

- In Bamendjou: the village razed after days of collective torture.

- In Bandjoun: schoolchildren abducted and never seen again.

It was a war—no, a massacre—cloaked in silence, enforced by terror. Survivors knew that speaking out meant risking death.

Even into the 1960s, after independence, the hunt for “rebels” continued. Cameroonian authorities, backed by France, pursued extermination campaigns with the help of Corsican mercenaries, French commandos, and local militias.

The Bamiléké people paid a double price—both ethnic and political. To be Bamiléké meant potential UPC sympathies, thus being deemed “subversive.” To be a UPC supporter meant becoming an enemy of the state. A deadly cycle.

A Genocide in Subtle Terms?

The word “genocide” was never used by French institutions. Yet scholars like Mongo Beti and Thomas Deltombe speak of a deliberate program of destruction. Numbers are hazy—archives buried, destroyed, censored. But confidential military reports speak of “pacification by terror,” of “zones to be neutralized,” of “forced population concentration.”

The “regroupment villages” became control camps: people were starved, isolated, their social ties broken. Disease spread. The Bamiléké social fabric was methodically dismantled.

Independence under tutelage: Ahidjo, Paris and the pursuit of resistance (1960–1971)

On 1 January 1960, Cameroon gained independence—but the gunfire did not cease. It simply changed hands. Barely sovereign, the country became a proto-Françafrique client state under Ahmadou Ahidjo—with full backing from Paris6.

A Northern Fulani Muslim and former colonial bureaucrat, Ahidjo had been molded by French officials. He reassured them: he would not contest economic agreements or the French military presence. In return, Paris gave him carte blanche to “pacify” the country—on his terms6.

From 1960, he introduced an authoritarian constitution and banned all opposition political parties. The UPC, still fighting, was branded a “terrorist” organization. The state mobilized all its resources to hunt the guerrillas.

Between 1960 and 1971, guerrilla fighters were hunted as foreign enemies. Entire villages were encircled, guerrillas tortured and summarily executed, bodies displayed in public as warnings.

Key resistance figures fell one after another:

- Félix-Roland Moumié, poisoned with polonium in Geneva in 1960 by a French agent.

- Ernest Ouandié, captured, summarily tried and executed publicly in Bafoussam in 1971.

- Abel Kingué, arrested and tortured to death in Yaoundé.

- Bishop Ndongmo of Nkongsamba, suspected of UPC sympathies, exiled to the Vatican.

The new “African” regime continued colonial policies: suppression, concealment, historical rewriting.

France remained no bystander: supplying military training, weapons, advisers, and funds to Cameroon. French officers like Colonel Jean Lamberton participated directly in operations. Independence became “monitored independence.”

In 1961, the signing of cooperation agreements between Paris and Yaoundé formalized vassalage—French control of resources, military oversight, diplomatic backing—and official silence on past crimes.

In schoolbooks, Um Nyobè was erased; the UPC demonized. No memorial honors the resistance fighters who died for true independence. Cameroonian children grow up with a truncated memory—where the real heroes are portrayed as villains.

The Cameroonian state became the guardian of a cloaked colonial peace. The expression “independence war” remains absent from official vocabulary to this day.

Confiscated memory, truth in the making

There is no monument to the dead of the Cameroon War.

No national day of commemoration.

No apology.

And for a long time, no words.

From 1955 to 1971, a colonial war ravaged a country, destroyed families, and killed its brightest leaders. Yet that war was labeled “unrest,” “law enforcement operations,” “tribal conflicts”… anything but what it truly was: a fierce, anti-colonial, Afrocentric war of independence systematically suppressed7.

For decades, survivors were silenced. Archives were locked away, historians threatened, witnesses ignored.

And yet the truth did not die. It lives on in oral narratives, in Bamiléké funeral chants, in the heavy silences of elders, in villages with scorched houses, in anonymous graves. And today, it is resurfacing.

Thanks to the work of historians, journalists, artists, and families of the disappeared, the memory of this war is gradually emerging from oblivion. Documentaries are being made. Books are being published. Activists demand justice. The veil is being torn away.

And this unveiling does not concern just Cameroon. It confronts France with its colonial shadow, the reality behind its “civilizing mission,” and the toxic legacy of Françafrique. It also confronts Africa itself: its post-independence elites, its silences, its responsibilities in transmitting memory.

To recognize this war is to repair history. It is to give a name to the dead. It is to identify the executioners. It is to remember that independence was not granted—it was taken.

And that those who wrested it away deserve much more than silence.

Sources and further reading

- Mongo Beti, La France contre l’Afrique – Retour au Cameroun (La Découverte, 1993)

- Thomas Deltombe, Manuel Domergue, Jacob Tatsitsa, La Guerre du Cameroun – L’invention de la Françafrique (1948–1971) (La Découverte, 2016)

- Achille Mbembe, La naissance du maquis dans le Sud‑Cameroun (1920–1960) (Karthala, 1996)

Notes

- A mandate was a territory entrusted to a colonial power by the League of Nations after 1919, supposedly to guide it toward autonomy—but effectively managed as a colony without accountability. French Cameroon remained a dominated territory until its 1960 independence.

- In 1957, France had over 15,000 troops in Cameroon, using T‑6 Texan bombers, phosphorus grenades, flamethrowers, and counter-insurgency agents trained in Algeria. Napalm—later used in Vietnam—was tested in Cameroon’s forests.

- Before Algeria, Cameroon served as a testing ground: from 1955–1960, “law and order” tactics included torture interrogations, no-go zones with total curfews, planted fake letters and radio broadcasts, and recruitment of mercenaries and local militias—later applied in Algeria, Chile, Vietnam, etc.

- Nyobè’s autopsy was never published; witnesses say he was hit by over 15 bullets. The military archives on the 13 September 1958 operation remain classified.

- Before 1955, the Bamiléké region had high population growth, literacy, and school attendance. Between 1956–1971, colonial censuses recorded sudden unexplained drops. In 2005, a French parliamentary mission spoke of “mass atrocities zones,” but no judicial follow-up occurred. No official recognition of these mass crimes by France or Cameroon followed.

- De Gaulle called Ahidjo “a model of stability for Africa.” The DGSE retained a Central Africa unit advising Cameroonian authorities into the late 1980s. No French officials involved in the 1955–1971 repression were prosecuted; France acknowledged “violence,” never “war” or state crimes.

- Several unofficial mass graves have been identified by geologists and anthropologists in western Cameroon, but remain unexcavated. French military archives are largely inaccessible. DNA studies might identify some executed resistors. A Franco‑Cameroonian truth and reconciliation effort is still pending.

Summary of Sections:

- The war France tried to erase

- Colonialism, UPC, and independence aspirations (1922–1955)

- 1955: War breaks out, but remains unnamed

- Hidden warfare: espionage, torture, counter-insurgency

- Assassination of Um Nyobè: a state target

- Bamiléké: target of a “dirty war”

- A softly spoken genocide?

- Tutored independence: Ahidjo’s anti-resistance hunt (1960–1971)

- Confiscated memory, emerging truth