Militiaman, British colonel, anti-colonial insurgent, political prisoner… Jean Kina embodies one of the most unusual and least-known paths of the Haitian Revolution. This is a look back at the complex journey of a man who, between Saint-Domingue, London, and Martinique, defied the dominant narratives of colonial history.

Jean Kina: Between collaboration, resistance, and oblivion

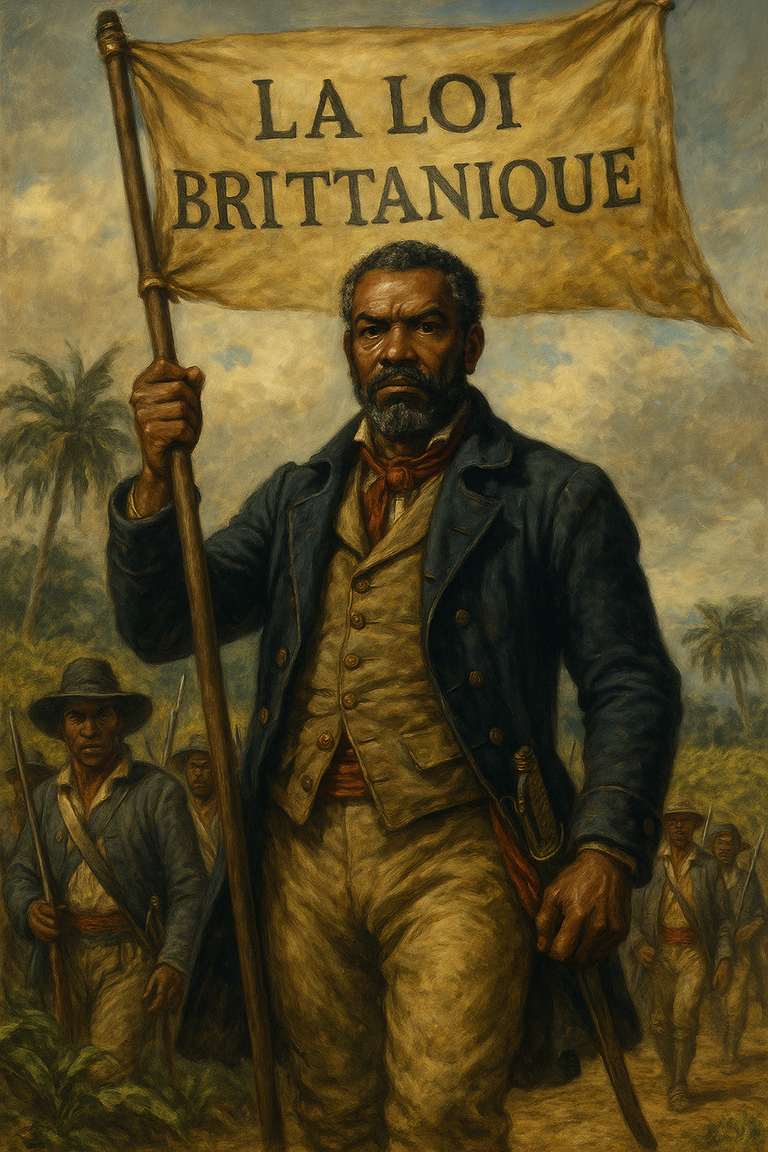

Martinique, December 5, 1800. Leading a group of about thirty armed men, Jean Kina—former slave turned soldier—raises a banner with a surprising inscription: “British Law.” The small group, mostly made up of free men of color, marches silently from Fort-Royal, stopping at plantations to denounce the injustices endured by Black people and the emancipated. No gunfire, no bloodshed. Just the clamoring of a silent, resolute revolt fueled by hope for a fairer law—even if it came from a rival colonial empire.

This striking scene is absent from schoolbooks. Its central figure, Jean Kina, remains erased from historical memory, overshadowed by the brighter legacies of Toussaint Louverture, Dessalines, or Christophe. Yet his journey defies all categorization: a slave turned war leader, a counter-revolutionary turned anti-colonial insurgent, a double agent between French and British forces—Kina embodies the complex trajectories of Afro-descendants caught in revolutionary upheaval.

Why has this man—both a battlefield strategist and political leader—been excluded from the mainstream narratives of the Haitian Revolution? Was it the ambiguous nature of his alliances? Or the fact that he initially served interests opposed to Haitian independence before embracing its core demands?

Nofi proposes revisiting Jean Kina’s story through a decolonial lens, reconstructing the multiple layers of his commitment. This is not about glorifying a hero, but about giving voice to a man who, in a world ablaze, never stopped fighting with dignity.

The beginnings of Jean Kina: Black militiaman in service of the colonists

On the eve of the Haitian Revolution, Saint-Domingue was the most lucrative colony of the French Empire—and the most explosive. In this rigidly racially stratified society, tensions ran high. Whites held political and economic power, free people of color demanded equal rights, and enslaved people—the majority—lived in daily brutality.

It was in this combustible context that Jean Kina, still enslaved, entered the scene. Originally from the Grand’Anse region, he was enlisted by white planters into a militia of armed slaves formed to suppress uprisings by free people of color. The irony is bitter: the oppressed are mobilized to crush other oppressed, a tactic of division and manipulation typical of the colonial system.

Kina was not alone. Faced with the 1790–91 revolts, several Black militias were created to protect white-owned property. Their implicit promise: rewards, sometimes even emancipation, in exchange for loyalty. But in this equation, loyalty was never absolute.

For Jean Kina, this period marked the start of a strategic trajectory: he understood early on the rules of the colonial game and joined it not out of allegiance, but out of survival. By wielding arms for the masters, he gained vital knowledge of the terrain, tactics, and people. He also learned that in a world at war, those who master violence can become indispensable—and therefore negotiable.

Far from casting him as a “traitor,” this phase reveals a pragmatic awareness of political complexity: for an enslaved person, any armed action could be both collaboration and a potential seed of revolt.

From the british empire to irregular warfare

When British troops landed in Saint-Domingue in 1793, their goal was clear: exploit the revolutionary chaos to weaken Republican France and reclaim a colony as precious as it was strategic. To that end, they sought local allies, including royalist planters and rebellious slaves. In this fluid game of alliances, Jean Kina aligned with the British, who quickly recognized his value as a military asset.

He was appointed colonel in the British army—an exceptional rank for a Black man (even a former slave) in an imperial force. This appointment was no act of charity; it reflected the pragmatic respect he commanded from his British superiors. Kina was not just an armed man—he was a field commander, a forest terrain expert, and a formidable leader of men.

Unlike the traditional European-style battles, Kina practiced bush warfare, typical of Saint-Domingue’s mountainous and inaccessible regions. Ambushes, harassment, terrain mastery—he employed tactics rooted in both his colonial experience and popular resistance traditions.

This irregular warfare, initially scorned by Europeans, became a strategic nightmare for their conventional armies. It granted Kina superiority, tactical mastery, and above all, rare autonomy. On the battlefield, he was no longer the conscripted ex-slave—he was a respected and effective commander.

But whom was he really serving? The British Empire? Himself? The hope of overturning unjust orders? In truth, Jean Kina represents a generation of Black political actors who navigated the cracks between two warring empires—not to serve them, but to use them, seizing opportunities as they arose.

Between two empires: Conspiracies, alliances, and double play

After the British withdrawal from Saint-Domingue, Jean Kina was invited to London. This visit to the imperial capital was more than exile—it was recognition. In Whitehall, he met government officials as well as exiled French planters interested in his networks and colonial influence.

Among the intrigues he became involved in was one worthy of a political thriller: a plot, supported by Pierre Victor Malouet, to kidnap Toussaint Louverture’s sons, then studying in France. The aim was clear: use the children as political leverage against their father, who had become the dominant figure in Saint-Domingue. Kina, with his on-the-ground connections, was the perfect operative for such a mission. The plan failed but reflected the constant double game surrounding him.

After London, Kina was sent to Martinique, a French colony then under British occupation. There, he married Félicité-Adelaïde Quimard, a free woman of color—a detail that highlights his gradual integration into the networks of emancipated Creoles, often key actors in local political movements.

But Martinique was far from peaceful. In December 1800, Jean Kina led a peaceful uprising against local authorities accused of trying to restrict manumission laws. With about thirty men, he marched through the countryside, gathering support and protesting on behalf of free people of color and enslaved individuals. His message? British law as a shield against white abuses. He even carried a banner reading “British Law”—a provocative and strategic symbol.

Far from a riot, this movement was a political demonstration, a call for respect of basic rights. The British authorities’ response—neither repression nor trial, but discreet exile—shows just how much Kina had become both a rebel and a diplomatic actor.

Soft repression and penal exile

On the morning of December 6, 1800, British and militia forces in Martinique, under Colonel Frederick Maitland, surrounded Jean Kina’s men. Yet instead of the expected colonial repression, Maitland made a surprising choice: he offered amnesty in exchange for surrender.

Why such clemency? First, Kina had shed no blood. Second, Maitland, aware of the legitimacy of the free people of color’s demands, feared that a bloody suppression could spark wider revolt. Third, he knew Kina—his skills, his influence, his complexity. Crushing him could mean losing a valuable asset in future colonial power plays.

Kina accepted the offer. His men laid down their arms. No trial, no execution. But the trust was broken.

Instead of being judged locally, Kina was deported to London, imprisoned at Newgate Prison under the Aliens Act of 1793—a law targeting foreigners deemed dangerous or subversive.

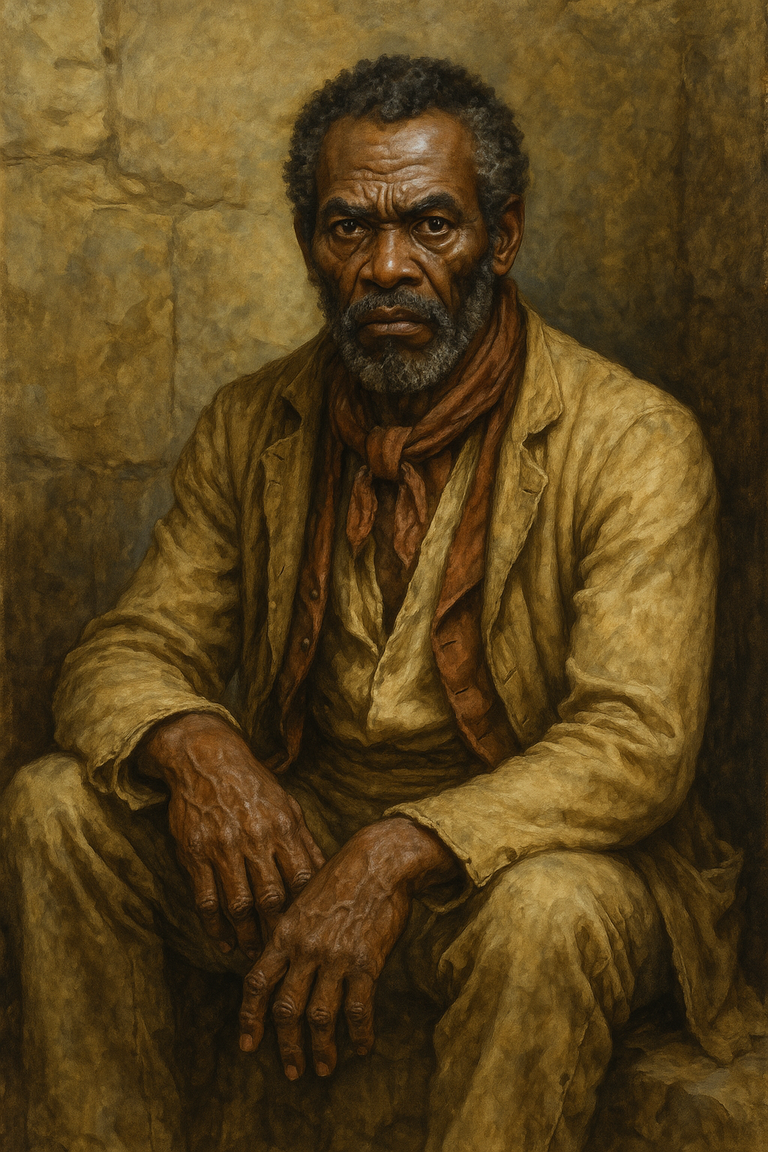

But the story did not end there. With the Peace of Amiens in 1802, briefly halting hostilities between France and Britain, Kina was released and returned to France. A hope for freedom? Not quite. He was imprisoned again—this time in a highly symbolic place: Fort de Joux, where Toussaint Louverture was also held.

At his side, his own son, Zamor, was also imprisoned. The parallel is striking: two major Black figures of Caribbean insurrection locked up in the same frigid Jura fortress. One would become a national hero; the other, a forgotten name.

This dual incarceration marked the cost of political ambiguity: neither loyalist nor fully revolutionary, Kina was a man the empires preferred to neutralize rather than recognize.

Final act: From prison cell to imperial army

In August 1804, Jean Kina and his son Zamor were finally released from Fort de Joux, a few months after Toussaint Louverture’s death in the same prison. There was no tribute, no official recognition. But there was an offer: to join the Army of Italy—not as decorated soldiers, but as carpenters, that is, manual laborers for Napoleon’s military campaigns.

This assignment may seem minor, even humiliating. Yet it reveals a brutal truth: at a time when the French Empire was restructuring and Haiti was declaring independence, men like Kina—neither fully aligned with imperial ideology nor fitting the heroic mold of the revolution—were used and then sidelined, often rendered voiceless.

The archives fall silent after this last mention. We do not know when or how Jean Kina died. No military records document his activity within the imperial army. His name vanishes, swallowed by history.

And yet, this erasure speaks volumes. It tells of the fate reserved for those who don’t fit neat narratives: the “good” revolutionaries on one side, the traitors or colonists on the other. Jean Kina was neither. He was a mobile actor, strategic, at times contradictory, but deeply rooted in his era and its struggles.

He was also a rare example of an autonomous Black man, wielding politics and military arts alike—his memory a challenge to linear narratives. In that sense, his disappearance is no coincidence: it is a historical choice shaped by racism, imperialism, and fear of nuance.

Jean Kina, a figure of post-slavery complexity

Jean Kina’s story eludes easy categorization. It unsettles because it forces us to let go of comforting myths: the pure revolutionary or the servile traitor, the untarnished Black hero or the empire’s pawn. It reveals a harsher truth: in the colonial tumult, the paths of insurgent Black people were often ambivalent, strategic, sometimes contradictory—but always deeply human.

Kina was a slave, militia leader, British colonel, conspirator, insurgent, prisoner, artisan. He negotiated, resisted, yielded, tried, retreated. Not out of weakness, but because he navigated a world of multiple betrayals, unstable alliances, warring empires, and betrayed revolutions. And in that world, he stood tall.

To rehabilitate Jean Kina is not simply to add another name to an already long mural. It is to give voice to all the Black actors of the Caribbean revolution whose journeys didn’t fit the official stories. It is to affirm that complexity is not a betrayal of the cause but a historical richness. Above all, it is to remind us that Afro-descendant struggles produced more than glorified heroes: they produced tacticians, thinkers, men and women capable of navigating the contradictions of their time.

In this era of memory revision, Jean Kina deserves to be remembered—not despite his complexity, but because of it.

Further reading

- David Geggus, Haitian Revolutionary Studies, Indiana University Press, 2002.

- Nathan Dize, “The Persistence of Félicité Kina: Kinship, Gender, and Everyday Resistance,” Nursing Clio, July 26, 2018.

- Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution, Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Mimi Sheller, Citizenship from Below: Erotic Agency and Caribbean Freedom, Duke University Press, 2012.

Table of Contents

- Jean Kina: Between Collaboration, Resistance, and Oblivion

- The Beginnings of Jean Kina: Black Militiaman in Service of the Colonists

- From the British Empire to Irregular Warfare

- Between Two Empires: Conspiracies, Alliances, and Double Play

- Soft Repression and Penal Exile

- Final Act: From Prison Cell to Imperial Army

- Jean Kina, a Figure of Post-Slavery Complexity

- Further Reading