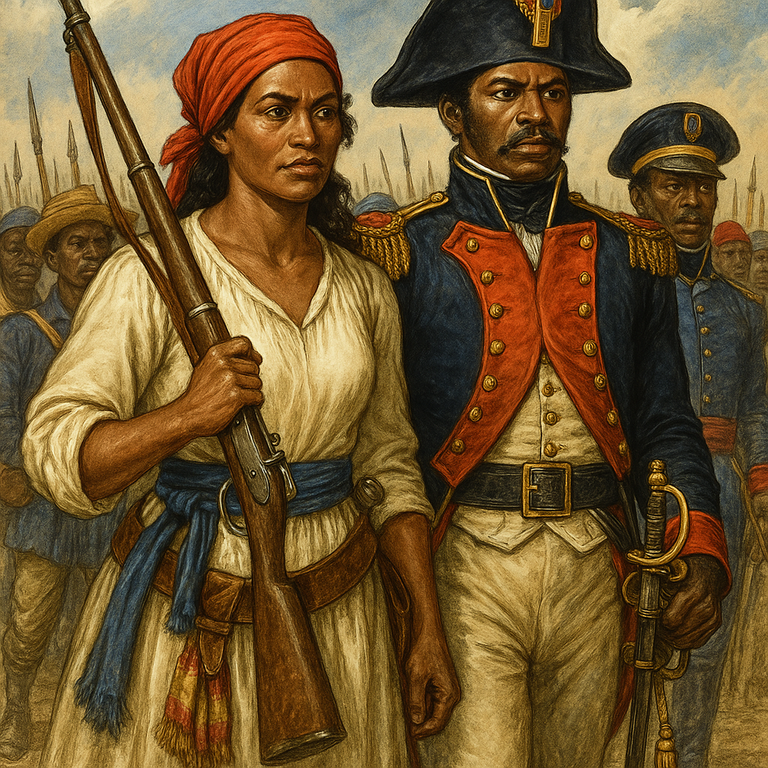

They fought, healed, poisoned, prophesied, gathered intelligence, buried heroes, and rallied the people. And yet, their names are often missing from the textbooks. Cécile Fatiman, Sanité Bélair, Dédée Bazile, Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière… These are the women of the Haitian Revolution. Warriors, mambos, resistors: a look back at those who, in the shadows, built the first free Black republic.

The heroines we never name

In most history books, the Haitian Revolution is written in the masculine. Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Henri Christophe… Their names echo through the centuries as emblems of Black resistance, the generals of a unique insurrection: a people in bondage overthrowing one of the most powerful empires in the world. Yet, in the gaps of the official story, a deafening silence remains—that of the women.

And yet, they were there. Not on the margins, but at the heart of the uprising—in the fields, in the camps, in battle, in trances at night, and in the guerrilla caves. They carried rifles, raised children on the run, treated the wounded with roots, dropped poison in cooking pots, and buried fallen leaders with their own hands.

They were named Cécile Fatiman, Vodou priestess and prophetess of Bois-Caïman.

Sanité Bélair, a legendary lieutenant, executed standing, eyes wide open.

Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière, military strategist at Crête-à-Pierrot.

Dédée Bazile, the sacred madwoman, last guardian of Dessalines’s mutilated body.

Romaine-la-Prophétesse, mystical warrior, transgressive woman and war leader.

Their involvement was not a footnote in Haiti’s epic. It was the backbone—a matrix of action and sacrifice without which the world’s first Black republic could not have been born.

But history, written by male victors or survivors, erased or distorted them—reduced them to folkloric, mystical, or secondary figures. Some have no grave. Others have only been superficially “reclaimed,” with no deep acknowledgment of their political, military, or intellectual role.

Restoring their place today is not a favor. It is a duty of memory, a political act, a feminist and Afrocentric endeavor. For in their gestures, their cries, their silences, and their rituals, these women already carried a powerful intuition: freedom cannot be won without women. And it never lasts if they are forgotten.

This is their story. Or rather: their return.

Living as a woman and a slave in Saint-Domingue

Even before the revolution ignited in 1791, the daily lives of Black women in Saint-Domingue were filled with visible and invisible chains. In the world’s richest colony—where sugarcane, coffee, and indigo generated fortunes for France—enslaved women endured the convergence of racial, economic, patriarchal, and sexual violence.

They were not only seen as labor to exploit but also as wombs to control. Their bodies were tools of forced reproduction. The Code Noir, in its cruel silences, tolerated and even encouraged the systemic rape of Black women by colonists. A child born to an enslaved woman remained a slave. This simple fact turned motherhood into a silent battlefield.

The rare surviving testimonies speak of children conceived in pain, pregnant women forced to work to exhaustion, infants torn from their mothers, and mothers who sometimes chose infanticide or suicide over seeing their children become property.

Amid this daily terror, subtle and radical forms of resistance emerged.

Some women feigned illness to slow down labor.

Others poisoned their masters—drawing on African traditions of justice through plants.

Some escaped to join maroon communities in the mountains, becoming messengers, healers, and Vodou initiates.

Their very survival was an act of rebellion. And already, in the shadows of the plantations, they were laying the foundations of a counterpower. An underground world of sisterhood, care, and secrets—a world that, when the revolution exploded, became the spiritual and logistical nerve center of the insurrection.

For before they were fighters, the women of Saint-Domingue were the first sentinels of dignity.

The ones who prepared, the ones who lit the fire

The Haitian Revolution did not begin with a scholar’s declaration or a military march. It began with a ceremony. A night. A trance. A fire. And at its heart, a woman.

It was August 1791, in the forest of Bois-Caïman in northern Saint-Domingue. Hundreds of insurgent slaves gathered in secret to vow an end to the colonial order. This founding moment, often called the “mystical baptism of the Revolution,” was led by a man and a woman: Dutty Boukman, the houngan, and Cécile Fatiman, the mambo.

Cécile Fatiman, born to an African enslaved woman and a Corsican colonist, was more than a Vodou priestess. She was an oracle, a guide, and a channel for rage. Through her songs, dances, and invocations, she infused the gathering with a sacred breath. This was not just a plot against the masters—it was a call to the loas, the African spirits of the Vodou pantheon, to join the liberation struggle.

This ceremony was not symbolic—it was operative. It sealed a pact, a collective commitment. It marked the end of submission. What followed were flaming plantations, raised swords, and slaves turned insurgents.

But Cécile Fatiman was not alone. She represented an entire network of mambos—often marooned priestesses who practiced medicine, divination, and resistance. In fugitive communities, they were the ones who healed, taught, and organized. They held the knowledge of roots and poisons, capable of bringing down a master without a gun.

Their knowledge—passed orally, body to body—was both spiritual and political weaponry. They knew that liberation had to be not only military but also ritual, cosmic, and psychological.

This revolutionary Vodou, passed on by women, became a space for Afro-Caribbean cultural reconstruction. In a colonial land that sought to erase languages, names, and lineages, these women preserved ancestral breath, living knowledge, and insubordinate strength.

And it was that breath that would set the system ablaze.

Women soldiers and strategists

The Haitian Revolution was one of the few 18th-century uprisings where women openly, massively, and sometimes commandingly took up arms. In a colonial society that had silenced them, they responded with gunpowder, swords, and fire—unmasked.

Some carried rifles, others machetes, still others drums or cannons. But they all shared one stance: a firm refusal to leave the war of liberation to men alone.

The most striking example is Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière. Though the wife of a rebel officer, she was also a military leader in her own right. In 1802, during the famous Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, she fought on the front lines against Napoleon’s troops. According to military accounts, she commanded a garrison, wore the uniform, and fought with a bayonet among the men. Even the enemy was impressed by her courage. She entered legend as the “Black Joan of Arc,” though the European-inspired nickname belies the originality of her stance.

Another key figure: Sanité Bélair. Born free in a colony where Black freedom was rare, she joined the revolutionary army early, became a lieutenant under Toussaint Louverture, and led cavalry troops. Captured by the French, she was sentenced to death. On the day of her execution, she refused a blindfold and died standing, facing her executioners. She was barely 20.

Their bravery was not marginal—it drew from a deep African tradition of women warriors, from the Dahomey Amazons to Ashanti queens to Congolese fighters. This transatlantic memory was not erased by slavery—it was reactivated by the Revolution.

Some women didn’t fight directly but played key tactical roles:

- Transporting arms and ammunition across enemy lines

- Coordinating guerrilla logistics in the mountains

- Acting as liaisons between battalions across plantations

These roles weren’t auxiliary—they were vital in a mobile, asymmetric war of ambushes and counterattacks.

What’s most striking is that these women didn’t demand equality in the abstract—they demonstrated it on the battlefield. Often at the cost of their lives. For when captured, they faced the same punishments as men: execution, without mercy.

They weren’t just heroic exceptions. They formed a shadow army—often ignored, always essential

Between tactics, sacrifice, and exploitation

In every war, women’s bodies become a battlefield. The Haitian Revolution was no exception. But what sets this period apart is the strategic versatility with which women mobilized their bodies: at times as weapons, at times as shields, sometimes as bargaining tools, and other times as spaces of resistance.

Some women, especially those with access to cities, markets, or colonial barracks, served as spies or scouts. Disguised as street vendors, laundresses, or sex workers, they gathered intelligence on French troop movements, battle plans, and arms or food caches.

Their strength lay in their social invisibility: no one suspected them. And they turned this lack of attention into a military advantage.

Other women used seduction or sexual relations—voluntary or not—to obtain:

- confidential information,

- temporary protection,

- the release of relatives,

- or tools for political or economic negotiation.

Here, consent is often ambiguous—uncertain, coerced. Some women transformed that constraint into a lever. Others endured it, as part of the continued violence of slavery. Male revolutionary narratives would later glorify their “sacrifice” without questioning the patriarchal structures that exposed them to such conditions.

Some figures—like Marie Roze Adam, wife of Romaine-la-Prophétesse—are known for organizing networks of influence through marriage alliances, mystical ceremonies, and esoteric practices, blending sexuality, spirituality, and revolutionary diplomacy.

At the same time, we must mention the violence committed by allies. Even within Haitian forces, some women were exploited, raped, relegated to forced “logistics” or menial tasks. The revolution did not always protect them. They had to fight on two fronts: against the colonial enemy and against the machismo of their comrades-in-arms.

And yet, they held on. They persisted. They understood that their bodies were not merely flesh or suffering—but political territory. And on that territory, they planted the seeds of a Black, anti-colonial, and deeply embodied feminism.

Madness, suffering, and sisterhood

Some female figures of the Haitian Revolution didn’t wield rifles or wear uniforms. They carried something else: pain, mourning, visions. Their role was no less revolutionary—it was simply different. On the margins of military history, they embodied living memory, sacred mourning, suffering transfigured into political action.

Such is the case of Dédée Bazile, known as Défilée-la-Folle (“Défilée the Madwoman”). Her nickname says it all—or rather, hides it all: the trauma, the abuse, the violence of a system that, by crushing bodies, sometimes shattered minds. Dédée, a young Black woman raped repeatedly by her master, became a wanderer, an outcast, “mad” by the standards of the time.

And yet, she performed a monumental act. On October 22, 1806, after the assassination of Haitian head of state Jean-Jacques Dessalines—whose mutilated body had been abandoned and trampled in the streets of Port-au-Prince—she came to retrieve it.

With her hands, she gathered the remains, washed away the blood, protected what was left. She watched over his body and arranged for his burial. Alone.

She, who held no title. She, who was “mad.”

This act, which might seem anecdotal in military history, is in fact one of the most powerful expressions of revolutionary sisterhood. Défilée did not just bury a man. She restored the dignity of a people. In her erratic silence, in her caring gestures, she embodied the sacred “madness” of the oppressed who refuse erasure—even after death.

Défilée-la-Folle is the most well-known, but she was not alone. Other anonymous women—widows, nurses, mystics—played the role of “pain keepers,” essential to any lasting revolution. They were the ones who mourned the dead, healed the wounded, told stories around the fire, sang names, and engraved memory into gestures. They formed a revolutionary matriarchy—oral, often erased, but always transmitted.

Today, Défilée is honored in Haiti as a sacred figure. Artists pay tribute to her, poets resurrect her, activists invoke her.

Not for her “folklore,” but for what she represents: the irrational, feminine, tenacious heart of Haitian sovereignty.

The Ambiguities of Gender and Race

Within the grand epic of the Haitian Revolution lies a chapter often left in silence or approached with unease: the fate of white women. Victims or accomplices? Targets or bystanders? The question is delicate, for it touches on the moral limits of liberating violence, and the tragic intersection of gender, race, and power.

In 1804, after more than a decade of war, betrayal, massacre, and resistance, Haiti declared its independence. But this was no symbolic independence—it was a bloody break. Under Jean-Jacques Dessalines’s leadership, the remaining white French population was massacred, in an act the Haitian leader deemed necessary for the survival of the Black nation.

Among the victims were men, families… and women. Period accounts, including European ones, speak of rapes, forced marriages, and delayed executions. White women were often killed last—sometimes temporarily spared, sometimes used as bargaining chips or propaganda tools.

But Dessalines, in his logic of colonial extermination, eventually drew a hard line:

“There can be no eradication of white power if we allow the reproductive matrices of that power to survive.”

In other words: white women, even non-combatants or mothers, were perceived as a “genetic, political, and civilizational risk.” A brutal, radical, tragic logic—yet one that becomes comprehensible in the context of a people subjected to generations of unspeakable atrocities.

Still, the ambiguity remains. Not all white women were complicit. Some had been married by force, some condemned the violence, some protected enslaved people or sought to escape the colonial system.

The Haitian national narrative has never fully resolved this dark chapter. On one hand, it glorifies the eradication of colonial presence. On the other, it avoids discussing the massacred white women—for fear of tainting the legitimacy of the founding act. This silence has enabled colonial reinterpretations that depict the Haitian Revolution as “barbaric,” “unjust,” or “out of control.”

But what must be understood is that this breaking point was the result of long-accumulated violence and systematic dehumanization.

And if the liberation of one sometimes implies the erasure of another, it must always be judged in light of what came before.

In this tension between justice and vengeance, between reparation and violence, women’s bodies—both Black and white—became the symbolic battlefield whose scars still linger in collective memory.

Why their memory still disturbs

They shed blood, shed tears, overthrew masters, raised leaders, healed the wounded, bore arms, buried the dead, invoked the loas, and passed on the flame.

They were there—at the heart of the most radical uprising of the modern era.

And yet, history erased them.

The Haitian Revolution is celebrated as the founding act of global Black sovereignty—the cry of a people who said “no” to slavery, colonization, and dehumanization.

But that cry was not uttered by men alone.

It was carried, deepened, embodied by women.

So why are they still so absent from textbooks, monuments, and heroic narratives?

Because they disturb.

They disturb the hyper-masculine tale of heroism, where battles are won by bayonets and passed down from father to son.

They disturb colonial narratives, which prefer to depict Black women as passive victims or sexual beings—never as strategists, commanders, or visionaries.

They disturb even some national memories, which struggle to reconcile Vodou spirituality, female defiance, popular justice, and radical Blackness.

But their return is underway. Thanks to the work of scholars, artists, activists, and Afrocentric media, the names of Cécile Fatiman, Sanité Bélair, Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière, Dédée Bazile, Romaine-la-Prophétesse, and many more are resurfacing.

Not as minor characters—but as pillars.

Because recognizing their role is not just about historical accuracy.

It is about healing a wound. It is about telling young Afro-descendant girls today:

You are the legacy of a struggle. You are the memory of a revolt. You are the descendants of women who refused to bow—even to an empire. And their victory is yours.

SOURCES

- Philippe Girard, Rebels with a Cause: Women in the Haitian War of Independence (2009)

- Jayne Boisvert, Colonial Hell and Female Slave Resistance in Saint-Domingue

- Hourya Bentouhami, Notes pour un féminisme marron (2017)

- Joan Dayan, Haiti, History, and the Gods (1995)

- Elvire Maurouard, Des femmes dans l’émancipation des peuples noirs (2013)

- Maria Fumagalli, The Cross-Dressed Caribbean

- Terry Rey, The Priest and the Prophetess (2017)

- Mary Grace Albanese, Haitian Genealogies and Revolutionary Memory (2019)

Table of Contents

- The Heroines We Never Name

- Living as a Woman and a Slave in Saint-Domingue

- The Ones Who Prepared, the Ones Who Lit the Fire

- Women Soldiers and Strategists

- Between Tactics, Sacrifice, and Exploitation

- Madness, Suffering, and Sisterhood

- The Ambiguities of Gender and Race

- Why Their Memory Still Disturbs

- Sources