From the 19th to the 20th century, Europe and America organized exhibitions where non-European men, women, and children were caged, scrutinized, and humiliated in human zoos. A look back at this colonial practice at the intersection of scientific racism, economic exploitation, and imperialist propaganda.

Human Zoos: When the west displayed black bodies

In September 1906, visitors to the Bronx Zoo in New York crowded around an unusual cage. Next to a chimpanzee and an orangutan, a young man sat silently, wearing only a loincloth. His name was Ota Benga. He was 23 years old, from the Congo, and was displayed as a living curiosity—a “missing link” between man and ape. The zoo’s director justified the scene with pseudo-scientific claims, while the public chuckled, questioned, or protested. The humiliation was complete. The dehumanization, deliberate.

This chilling episode was not an isolated case. From Paris to Osaka, Antwerp to St. Louis, hundreds of men, women, and children were exhibited in so-called “human zoos,” also known as ethnological exhibitions. The concept? To parade “savages” from the colonies before Western eyes, portrayed as primitive specimens, often chained to racial or cultural stereotypes. Entire villages were recreated to stage this supposed “radical otherness.” The audience came to see, judge, compare—and ultimately believe in the superiority of the white man.

These practices were long denied, downplayed, or erased from collective memory. Yet they helped forge a deeply rooted racist imagination within Western societies. Deconstructing the history of human zoos is not just about denouncing a shameful past. It is also about understanding how the colonial gaze was constructed, how it still endures in insidious forms, and how Afro-descendant memory can—and must—reclaim its history.

Through a rigorous investigation and decolonial lens, Nofi explores the origins, mechanisms, staging, and lasting consequences of human zoos. Because to remember is also to resist.

The Genesis of Human Exhibitions

Long before human zoos became institutionalized during the colonial era, the West already had a habit of capturing the exotic. In pre-Columbian Tenochtitlan, Emperor Moctezuma collected people with unusual characteristics (albinos, hunchbacks, dwarves) in a menagerie meant to reflect cosmic order. In Europe, Renaissance elites staged displays of “foreign” individuals, living trophies symbolizing global power.

In the 16th century, Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici maintained a retinue of people from Africa, Asia, and the Americas, who were shown off in his Roman palace. These practices mixed fascination, exoticization, and implicit hierarchy. They already laid the foundation for a racializing gaze, where difference became spectacle and otherness became an object of domination.

In the 19th century, curiosity morphed into propaganda. The rise of colonial empires coincided with the emergence of racial anthropology, which sought to classify humans like animal species. Pseudo-science legitimized the colonial enterprise: the colonized were “inferior,” thus it was justified—if not noble—to civilize them by force.

World’s fairs became ideological showcases. It was no longer just about showing the Other—it was about proving they were inferior, bestial, lazy, “naturally” subordinate. Enter Carl Hagenbeck, a key figure: a former animal trader turned ethnic showman. In 1874, he organized one of the first exhibitions of “exotic” peoples in Germany: first the Sami, then Nubians, Inuits, Somalians. His idea? Recreate a pseudo-authentic setting—huts, dances, wild animals, crafts—to offer Europeans an “immersive experience”… of otherness.

Far from being marginal, these exhibitions were wildly popular. Crowds flocked by the millions. Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas became open-air human reserves. These scenes were not neutral—they reinforced the notion that the colonized were frozen in a primitive past, incapable of progress without European oversight.

Thus, human zoos were not mere spectacle. They were a cultural weapon of domination. A way to say: “Look at them. They need us.”

A staged racial hierarchy

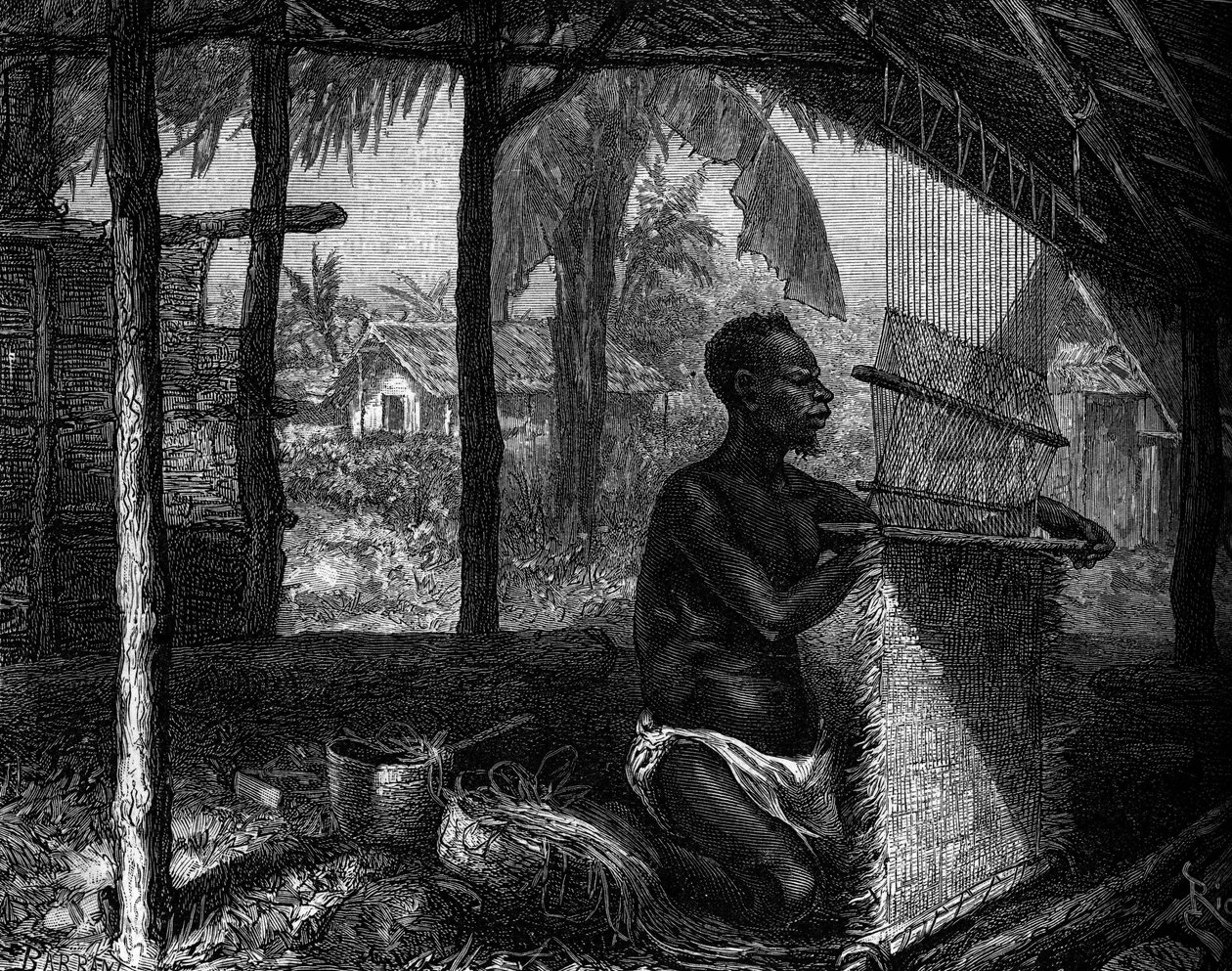

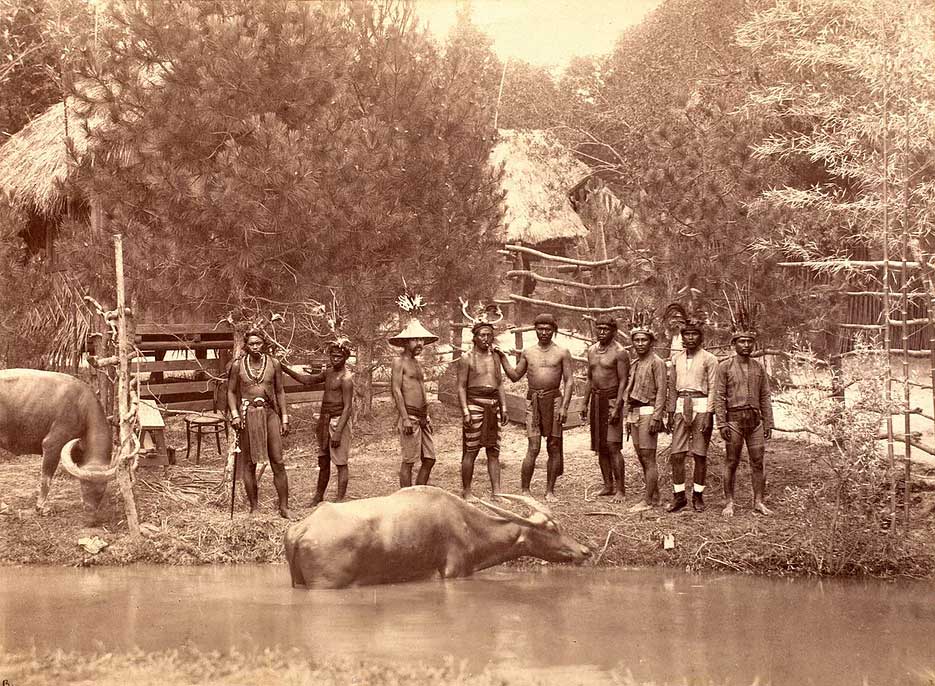

Human zoos didn’t just showcase people—they embedded them in carefully scripted scenes that validated colonial fantasies. From “Negro villages” to “Malagasy hamlets,” every detail aimed to create the illusion of immersion. The mud huts, “tribal” dances, improvised rituals were not authentic expressions—they were performances directed by Western organizers, often thousands of kilometers removed from the cultures portrayed.

Fiction replaced humanity. At the 1889 Paris World’s Fair, 400 people from French colonies were displayed as a main attraction. In Brussels in 1897, a “Congolese village” was built beside the Palace of the Colonies, complete with palm trees, drums, and an artificial river. The goal: naturalize the idea that Africans belonged to a wild, archaic world—and thus needed civilizing.

These exhibits were not just entertainment. They were meant to be educational—this is where racism masqueraded as science. In these “human fairs,” anthropologists, doctors, craniologists, and zoologists took turns measuring, photographing, and classifying bodies. Black people were compared to great apes; “pygmies” were studied as evolutionary anomalies.

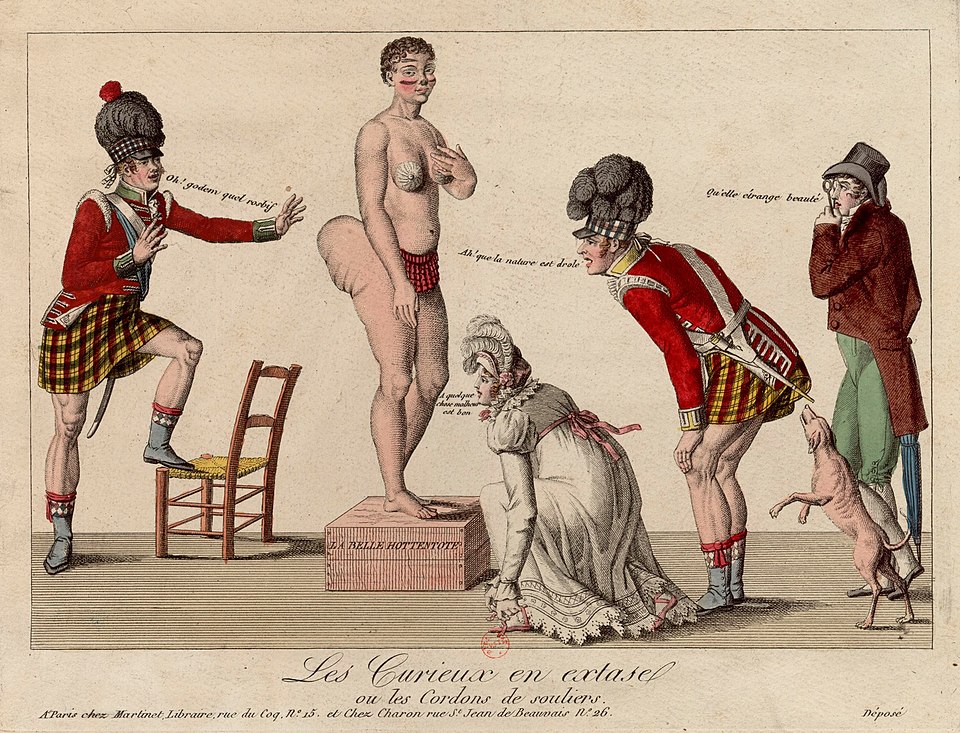

The infamous case: in Paris, Saartjie Baartman, dubbed the “Hottentot Venus,” was exhibited naked under the guise of science. After her death, her body was dissected and displayed at the Musée de l’Homme. Her body—like so many Black women’s—was reduced to an object of racial and sexual fantasy, suspended between bestial fascination and exotic condescension.

Human zoos were not just social oddities: they formed an entire industry. Organizers (showmen, zoo directors, colonial administrators) made vast profits. At the 1904 St. Louis Fair, over 1,100 Filipinos were displayed, generating massive revenue while reinforcing U.S. expansionist ideology after the Spanish–American War.

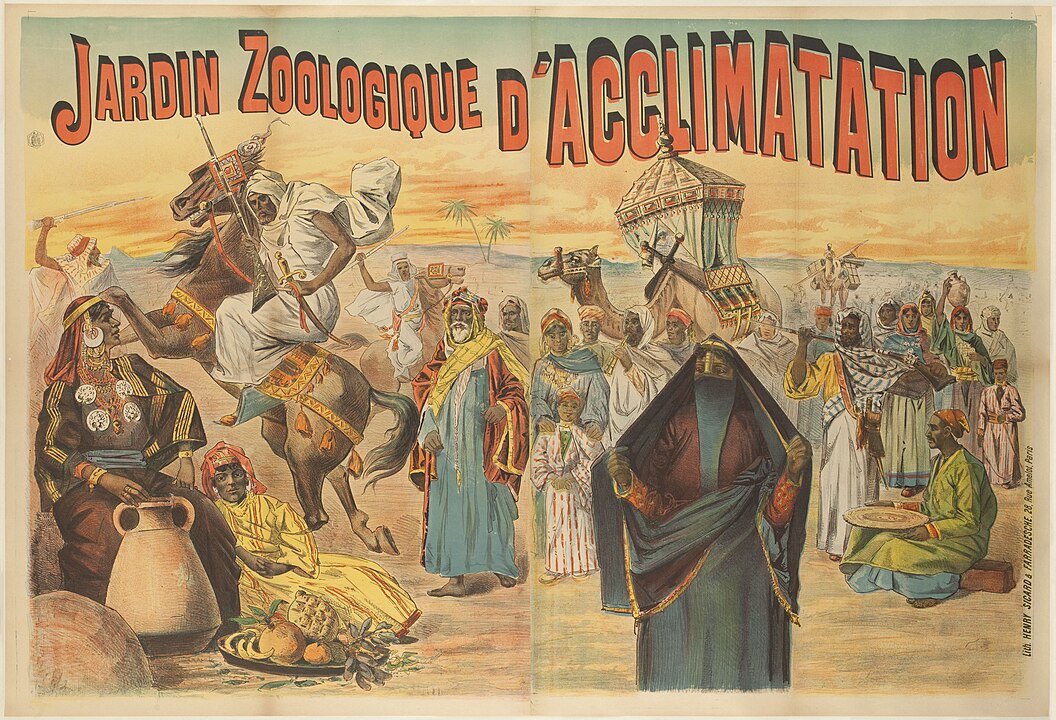

The success was such that some rulers used them as propaganda tools. In Spain, Queen Regent Maria Cristina of Habsburg set up a permanent human zoo in Madrid’s Retiro Park. In Paris, ethnographic exhibitions doubled attendance at the Jardin d’acclimatation. Racialized bodies had become cultural commodities—picturesque, profitable, and ideologically expedient.

Africa: The primary target of human zoos

Of all continents targeted by ethnic exhibitions, Black Africa was by far the most exploited, stigmatized, and caricatured. To imperial Western eyes, it epitomized the “savage”—both fascinating and repellent. The massive success of “African villages” in Europe rested on this fabricated image.

In Brussels in 1897, a Congolese village was constructed in Tervuren with over 250 people brought from the Congo Free State, the personal possession of King Leopold II. Meant to showcase “African authenticity,” these men, women, and children were lodged in crude huts, exposed to the cold, forced to simulate daily life under the gaze of spectators. At least seven died during the exhibition. In Paris in 1889, the “Negro village” drew nearly 28 million visitors.

In Madrid in 1887, Spain displayed Igorots from the Philippines in Retiro Park as proof of its civilizing mission. Africa—despite its vast cultural diversity—was reduced to a static backdrop, a single allegory of primitivism and inferiority.

Beyond the spectacle, human zoos shaped a toxic visual culture that would seep deeply into Western society. Postcards, posters, brochures, souvenirs: the Black body became image—a symbol of humanity reduced to mere physicality, to supposed animality.

Photos taken during these events were far from innocent. They were carefully framed to emphasize nudity, peculiar hairstyles, perceived wildness. The goal? Create an unbridgeable distance between the European and the African, morally justifying domination.

This racialized gaze influenced not only art and literature but also education, politics, and even advertising. The Black man was no longer just an “other”—he became the antithesis of Western modernity.

Resistance, outcry, and deconstruction

Though official history long erased the pain of human zoo victims, voices rose early on. In 1906, when Ota Benga was displayed at the Bronx Zoo, a coalition of Black pastors in New York launched a fierce campaign against the public humiliation. Reverend James H. Gordon condemned it as:

“An affront to the entire Black race…

We are already oppressed enough without being compared to monkeys in a cage.”

Despite official indifference, this protest was one of the first public acts of resistance against colonial dehumanization.

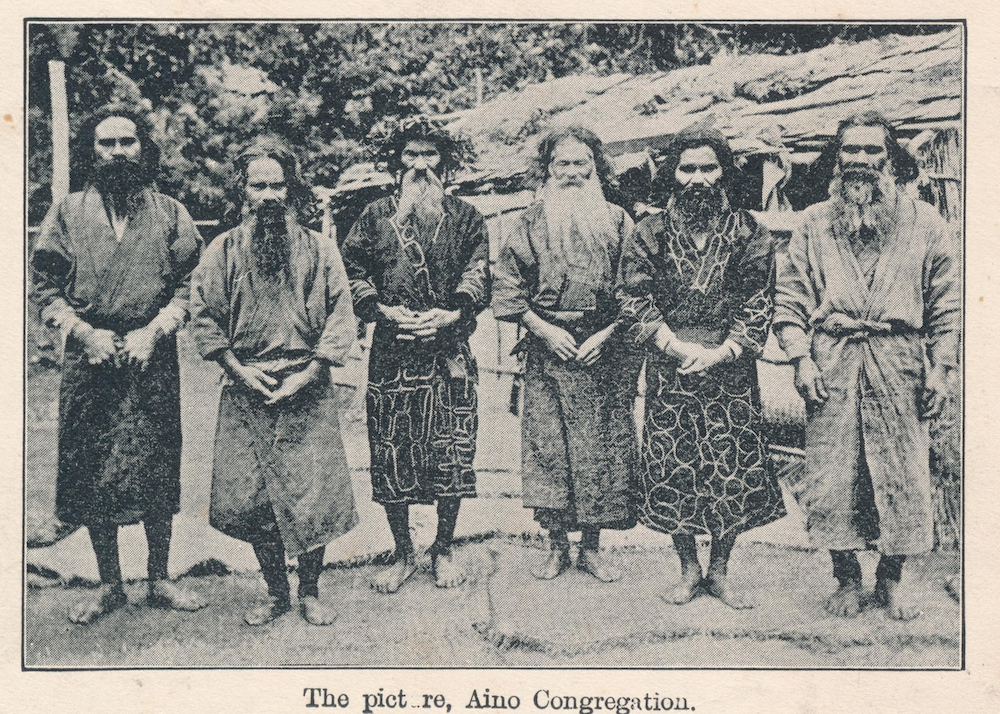

In Japan, in 1903, at the Osaka Exhibition, the display of Ainu, Koreans, and Formosans in “primitive” pavilions also sparked indignation. Japanese and Korean intellectuals, shocked by the spectacle, denounced the racist commodification. Though minor at the time, such critique gradually grew.

In 1931, as France celebrated its grand Colonial Exhibition in Paris, a small dissident event sought to counterbalance the narrative: “The Truth about the Colonies,” organized by the Communist Party. This counter-exhibition exposed forced labor, colonial violence, and human exploitation. Though sparsely attended, it marked a turning point in politicizing the issue.

Some artists, ethnographers, and travelers also began criticizing the racist logic of exhibitions. Writers like André Gide and journalists like Albert Londres published damning accounts of French colonial reality.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that real remembrance began. In the 1990s and 2000s, scholars like Pascal Blanchard and Nicolas Bancel brought human zoos back into public discourse. Traveling exhibitions, documentaries, books, public debates—bit by bit, the silence cracked.

In 2011, the exhibition “Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage” at the Quai Branly Museum sparked national shock. For many, it was the first direct confrontation with this deliberately obscured history. Since then, art, theater, and research have contributed to actively deconstructing this past—often with militant and decolonial intent.

Contemporary legacies and decolonial re-readings

Though we may think of human zoos as a thing of the distant past, their logic has not entirely disappeared. While people are no longer put in cages next to animals, the idea that some cultures are “spectacular,” “archaic,” or simply “other” still persists in many modern-day contexts.

In 2005, the Augsburg Zoo in Germany organized a reenactment of an “African village,” complete with real African artisans, dancers, and craft booths—in the middle of an animal zoo. Though the intention was educational, the symbolism was disastrous. A similar outcry occurred in 2014, when South African artist Brett Bailey presented his performance Exhibit B in London and Edinburgh. Through chilling tableaux of static Black bodies, the show aimed to denounce the logic of human zoos. However, performances were disrupted or canceled following protests from Afro-descendant activists who saw it as re-traumatizing.

Meanwhile, certain reality TV shows, tourist documentaries, and advertisements continue to exploit the “exoticism” of non-Western peoples—often in near-ethnographic settings, without critical reflection.

In response to these visual echoes of racism, many artists, activists, and intellectuals from African diasporas are reclaiming the gaze. Films, performances, photography, writing—Afrocentrism is emerging as a critical necessity. Works like The Couple in the Cage by Coco Fusco, or Sauvages: au cœur des zoos humains (a documentary by Pascal Blanchard), reexamine this history through the eyes of those long denied their own perspective.

The restitution of stolen human remains and cultural objects is part of this movement. In 2002, after sustained campaigning, the mummified body known as the “Negro of Banyoles” was finally returned to Botswana—170 years after it had been taxidermied and displayed in Spain.

One of the most pressing battles is that of transmission. Even today, few school textbooks seriously address the topic of human zoos. Yet this is a crucial chapter in understanding the foundations of modern racism. Teaching about these exhibitions means uncovering how racial hierarchies were fabricated, disseminated, and legitimized by political, scientific, and cultural institutions.

In the face of organized forgetting, memorial initiatives are multiplying: traveling exhibitions, conferences, university seminars, educational projects… Often led by Afro-descendant collectives, these efforts work toward a radical reclamation of history.

What human zoos reveal about Us

Human zoos are not a historical anomaly—they are a revealing lens. They lay bare the most insidious elements of colonial ideology: its ability to dehumanize in the name of science, to entertain in the name of civilization, to dominate while pretending to educate. They show us a time when the Black man, the colonized man, the “Other” man, was no longer seen as a subject—but as an object to be observed, categorized, consumed.

These exhibitions were not isolated incidents or marginal curiosities. They were a central component of the imperial machine, where economic interests, racist fantasies, and political ambitions converged. The bodies on display—whether African, Asian, Polynesian, or Indigenous—remind us of a painful truth: humanity was not always granted to everyone.

But it would be too easy to relegate these practices solely to the past. The legacy of human zoos still haunts our present. It manifests in cultural stereotypes, biased narratives, unequal gazes, and the silences of education. That’s why speaking about them is not a luxury—it is a necessity.

Revisiting this history means facing a disturbing mirror—the reflection of a civilization that, in proclaiming its superiority, forgot its own humanity. It is also an opportunity to do justice to the invisible, to restore the voices of those once silenced, and to build, step by step, a decolonized memory.

The goal is not guilt—but repair. And to repair, we must first recognize. Remembering human zoos means refusing to tolerate their resurgence in any form. It means declaring, loud and clear: never again.

Further reading

- Pascal Blanchard, Nicolas Bancel, and Sandrine Lemaire, Human Zoos: From the Hottentot Venus to Reality Shows, La Découverte, 2002.

- Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain, University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Dominika Czarnecka, “Black Female Bodies and the ‘White’ View,” East Central Europe, vol. 47, 2020.

- Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Alexander Geppert, Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Exhibition: Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage, Musée du quai Branly, Paris, 2011.

Summary

- Human Zoos: When the West Displayed Black Bodies

- The Genesis of Human Exhibitions

- A Staged Racial Hierarchy

- Africa: The Primary Target of Human Zoos

- Resistance, Outcry, and Deconstruction

- Contemporary Legacies and Decolonial Re-readings

- What Human Zoos Reveal About Us

- Further Reading