On May 13, 1888, the Empire of Brazil officially turned a dark page in its history by enacting the Lei Áurea (“Golden Law” in Portuguese), a radical decree that unconditionally abolished slavery. Yet behind this historic text, a complex reality still persists to this day.

A Historic but Late — Abolition

On May 13, 1888, with a gesture as brief as it was symbolic, Princess Isabel, the Imperial Regent of Brazil, signed what remains one of the most significant founding acts in Brazil’s modern history: the Lei Áurea, or “Golden Law.”

At the time, Emperor Dom Pedro II was in Europe for health reasons. It was therefore his daughter, acting as regent, who politically carried out this pivotal decision, defying the opposition of part of the landowning elite. Long resistant to abolitionist movements, the powerful slave-owning landlords (especially in the southern and central provinces of Brazil) saw their authority seriously weakened.

On the American continent, Brazil had long been one of slavery’s most entrenched strongholds:

- Over 4 million Africans were deported to Brazil during the transatlantic slave trade—nearly 40% of all enslaved people brought to the Americas.

- Slavery was deeply embedded in the sugar, coffee, and mining economies, and in colonial social structures.

- Even after the official abolition of the slave trade in 1850 (Eusébio de Queirós Law), internal exploitation and indirect forms of enslavement persisted, delaying the actual dismantling of the system.

The Lei Áurea, though short, marked a radical departure from prior legislative attempts. Its full text reads:

Article 1: “As of this date, slavery is declared abolished in Brazil.”

Article 2: “All provisions to the contrary are revoked.”

This extreme brevity reflected a clear intention: to avoid any restrictive interpretations, delays, or conditions for implementation. Unlike earlier laws—burdened with clauses, exemptions, or compensations for slave owners—the 1888 abolition was immediate and unequivocal.

However, this apparent simplicity concealed a deep flaw:

- No integration measures were implemented for former slaves.

- There was no land redistribution, no educational programs, no facilitated access to citizenship.

Freed from legal bondage, millions of former slaves were left without resources in a society that continued to marginalize them.

This institutional void laid the foundation for the racial and economic inequalities that still shape Brazil today.

A long road to abolition

The Lei Áurea did not fall from the sky: it was the slow and often disappointing result of a legislative process that began decades earlier. Two major laws had attempted to gradually erode the slave institution—without truly challenging its core foundations.

The Law of the Sexagenarians (1885), or Saraiva-Cotegipe Law, freed all enslaved persons over 60 years old. Yet again, this measure was more symbolic than structural:

The Law of the Free Womb (1871), known as the Rio Branco Law, was an official first step toward emancipation. It declared that all children born to enslaved women would be free. But this freedom was largely theoretical: until their 21st birthday, these children remained under the guardianship of their mother’s former owners, who retained use and control over them. Additionally, slaveholders could “surrender” these children to the state in exchange for a small financial compensation to avoid bearing the cost of raising them. The result: the status of children born “free” differed little from that of their enslaved parents, and the slave system remained intact in practice.

- Elderly slaves, often broken by years of grueling labor, were no longer considered economically valuable. Liberated without resources or support, many lived their final years in dire poverty, dependent on public charity or condemned to homelessness.

These two laws aimed to appease growing pressure from Brazilian and international abolitionists without provoking a backlash from powerful landowners. In practice, they allowed the system to survive by adapting it:

- In 1888, more than one million people were still enslaved in Brazil.

- The coffee, sugar, and cotton economies still relied heavily on forced labor.

The total, uncompensated liberation proclaimed by the Lei Áurea thus marked a far more abrupt break than these gradualist attempts.

Why abolish slavery in 1888?

While the Lei Áurea is often perceived as a shining humanitarian gesture, its adoption in 1888 was, in fact, the product of growing economic, diplomatic, and social pressures. Far from pure philanthropy, the abolition of slavery was also a strategic calculation.

By the 1880s, Brazil’s economy was entering a new phase. The slave-based model, once highly profitable, was becoming a costly burden:

- Feeding, housing, and surveilling slaves was increasingly expensive for plantation owners.

- Meanwhile, mass immigration from Europe—particularly Italians, Germans, and Portuguese—offered a cheap, malleable workforce without the maintenance costs of slavery.

In major coffee-growing regions like São Paulo, planters were already shifting to free labor, seen as more flexible, profitable, and less conflict-prone than traditional slavery. The old socio-economic slave model was collapsing under the weight of modernization.

For decades, Great Britain—Brazil’s leading trade partner—had actively pushed for the end of the slave trade and slavery worldwide. As early as 1845, the Aberdeen Act had allowed British ships to seize Brazilian vessels suspected of human trafficking.

By 1888, continuing to uphold slavery meant:

- Facing possible trade sanctions.

- Risking diplomatic isolation in an increasingly abolitionist Western world.

- Undermining Brazil’s ambitions for modernization and integration into global markets.

The Lei Áurea was also a message to the international community: Brazil wanted to be seen as a modern and civilized nation.

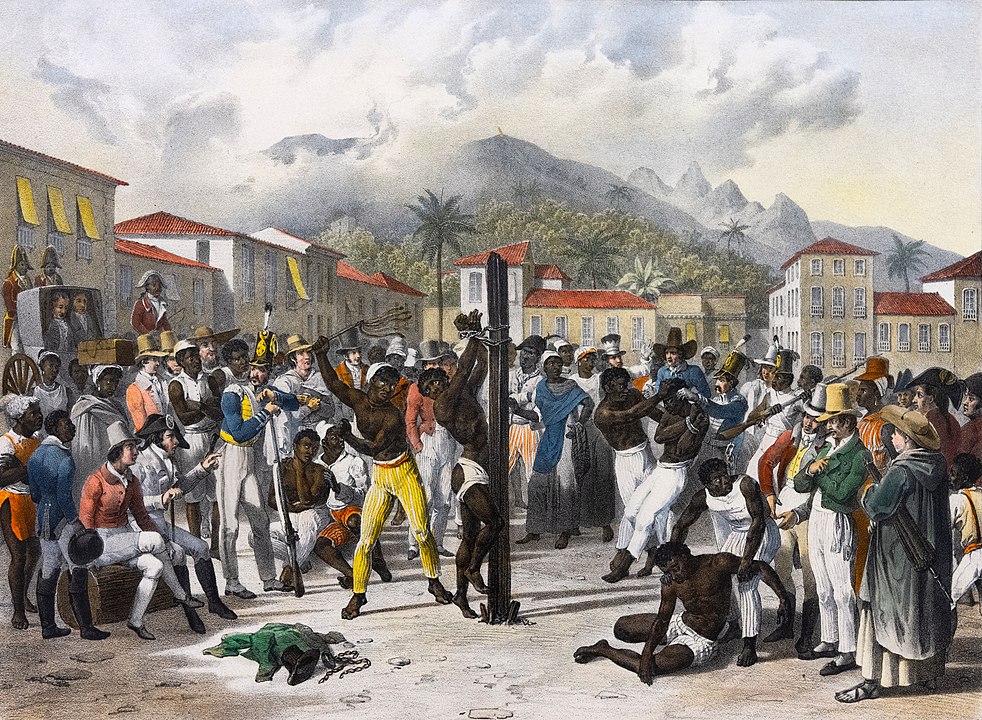

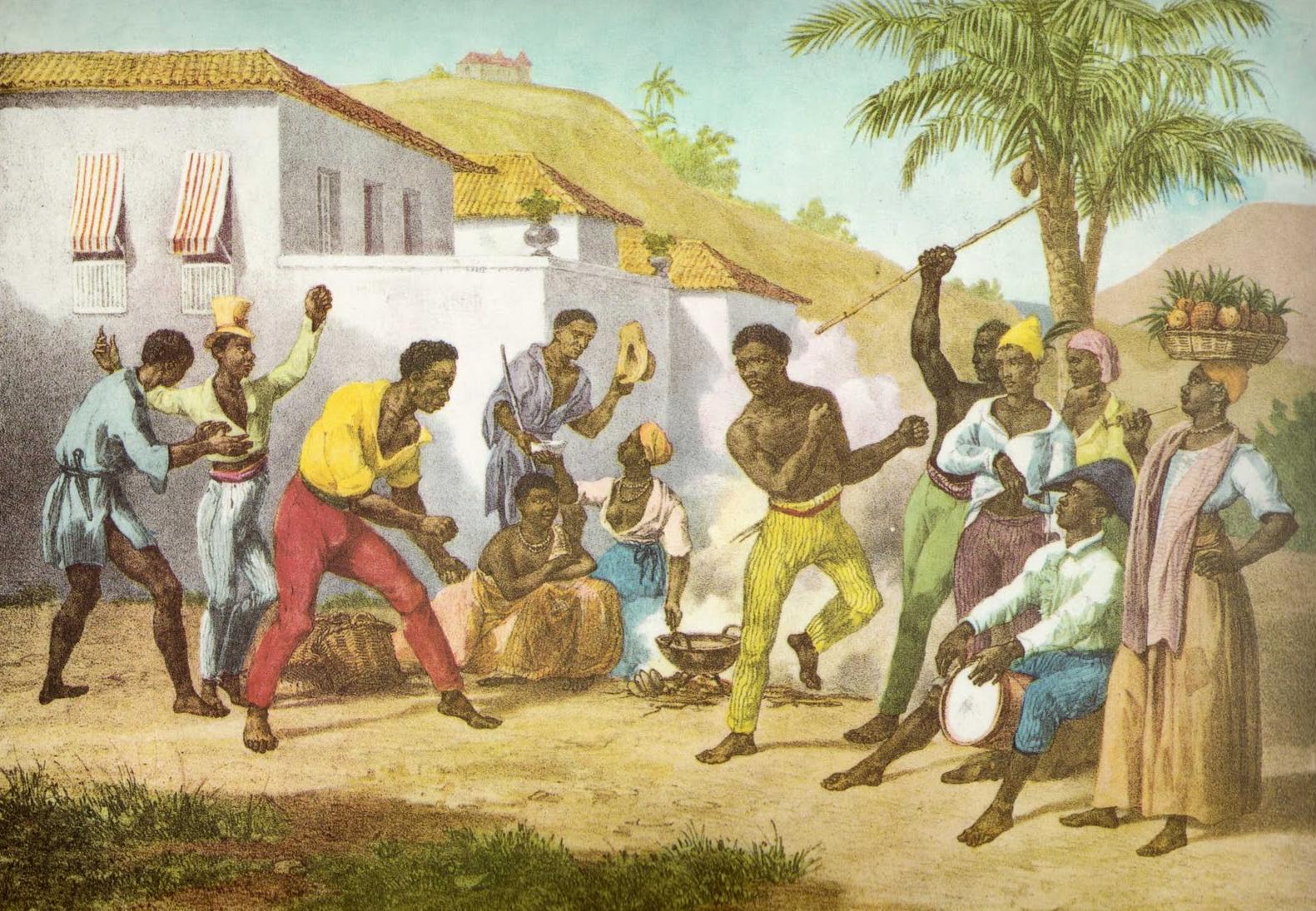

Far from being passive victims, enslaved Africans in Brazil led centuries of resistance: revolts, sabotage, and mass escapes.

One of the most spectacular forms of resistance was the creation of quilombos:

- Villages founded by escaped slaves, often in remote and inaccessible regions.

- Spaces of freedom, self-governance, and preservation of African cultures banned by colonial society.

- The most famous was the Quilombo of Palmares (17th century), which gathered up to 20,000 inhabitants under the legendary leadership of Zumbi dos Palmares.

Even after its fall in 1695, the spirit of Palmares survived and inspired generations of resisters.

By the 19th century, sporadic uprisings, escapes to quilombos, and unrest on plantations made slavery increasingly unstable and unmanageable.

Maintaining social order was costly; the system was collapsing from within.

Thus, the 1888 abolition was not a moral decision in isolation but the result of a systemic crisis: economic, diplomatic, and social. The Brazilian monarchy had no choice but to acknowledge an untenable reality.

Freedom without reparations

— Alejo Carpentier

The signing of the Lei Áurea in 1888 legally made millions of formerly enslaved individuals free men and women. But that freedom remained strictly formal.

- No land redistribution was planned.

- No compensation was offered for decades of forced labor.

- No measures were introduced to facilitate access to education, full citizenship, or the labor market.

Deprived of any economic means of survival, ex-slaves were abandoned within a rigid social system where skin color still determined destiny.

Many became impoverished farm laborers or crowded into urban outskirts, creating the first large rings of poverty around Brazilian cities—areas whose direct legacy is found in today’s favelas.

Legal freedom was not followed by true social inclusion. And it is this absence of concrete reparations that still explains the deep racial inequalities in Brazil:

- Afro-Brazilians remain overrepresented among poor populations.

- Access to higher education, leadership positions, and quality healthcare remains structurally imbalanced.

Political consequences: The end of an empirepire)

The abolition triggered a shockwave among Brazil’s economic elites:

- The great landowners, furious at having lost their “human capital” without compensation, withdrew their support from the monarchy.

- The traditional bond between the crown and the fazendeiros (landowners) was suddenly broken.

- Politically weakened and isolated, the monarchy had no firm base in a society eager to move on—not only from slavery but from the old regime.

Less than a year after the ratification of the Lei Áurea, in November 1889, a military coup ended the Empire of Brazil. A Republic was proclaimed, led by conservative elites with little interest in advancing real social reform for Afro-descendants.

By abolishing slavery without revolutionizing the social order, Brazil inherited a facade of racial democracy, where the proclaimed equality remained largely theoretical.

“If we had a map on which a red light lit up every place where Black slave revolts occurred on the continent, we’d see that from the 16th century to the present, there would always be a light shining somewhere.”

— Alejo Carpentier

This quote perfectly illustrates the continuous resistance of Africans and their descendants—from the colonial period to the present. The abolition was a major milestone, but the struggle for real justice has continued ever since—and still continues.ore.

Sources and references

- Stela Bueno – “Brazil Puts an End to Slavery,” www.herodote.net, published June 12, 2017

- “Brazil. Parlamento. Câmara dos Srs. Deputados”

Table of Contents

- A Historic — but Late — Abolition

- A Long Road to Abolition

- Why Abolish Slavery in 1888?

- Freedom Without Reparations

- Political Consequences: The End of an Empire

- Sources and References