While Christopher Columbus was searching for a new maritime route in 1492, Africa was experiencing a golden age of science, culture, and politics—one largely forgotten in dominant historical narratives.

While Columbus searched for America, Africa was writing history

The year 1492 marks a pivotal turning point in Western history.

The “discovery” of the New World by Christopher Columbus, under the patronage of Spain’s Catholic Monarchs, launched the European maritime expansion that would lead to centuries of colonial conquest. In the European imagination, this event inaugurated an era of Western “greatness” and “civilization” in contrast to continents portrayed as virgin, underdeveloped, or marginal to history.

Within this teleological narrative, Africa is relegated to silence—often depicted as a frozen, ahistorical space without its own internal dynamism. Yet this portrayal, crafted and perpetuated by colonial and Eurocentric accounts, overlooks a far more complex reality: in 1492, Africa was a living, diverse continent marked by powerful political, economic, cultural, and spiritual dynamics.

From Gao to Fez, from Kilwa to Lalibela, mighty kingdoms and flourishing urban societies animated the continent, trading with Asia, the Middle East, and even indirectly with Europe—well before Columbus’s caravels opened new oceanic routes.

This article seeks to break from simplistic narratives by restoring, through the lens of the latest historical research, the rich human, political, and cultural complexity of Africa on the threshold of the modern era.

It is not only a matter of factual correction, but also of reintegrating Africa into the global movement of civilizations at the close of the 15th century.

I. Powerful and structured empires

1. The songhai empire: The apex of a learned and conquering Africa

At the turn of the 15th century, the Songhai Empire reached its zenith, dominating much of West Africa’s Sahel region.

Rooted in an ancient commercial and military tradition along the Niger River, Songhai partially inherited the greatness of its predecessors (the Ghana Empire and especially the Mali Empire) while asserting its own historical legacy.

Under the dynamic reign of Sonni Ali Ber (1464–1492), the empire underwent rapid military expansion:

- The merchant cities of Djenné (conquered after a seven-year siege) and Timbuktu (taken in 1468) fell under Songhai control.

- Mastery of the trans-Saharan trade routes—crucial for commerce in salt, gold, ivory, and slaves—brought Songhai extraordinary economic prosperity.

- Gao, the capital, became a major political and commercial hub. Its markets brimmed with goods from Central Africa, the Maghreb, and even the Middle East. Gao was also a cosmopolitan city, home to Arab, Berber, Jewish, and African merchants.

Timbuktu, meanwhile, emerged as one of the Islamic world’s great intellectual centers:

- The Sankore Mosque and other madrasas drew students from across the empire, Egypt, and even Muslim Spain.

- The famous Timbuktu manuscripts—covering theology, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics—attested to a vibrant scholarly culture connected to the broader Islamic world.

The Songhai administrative system, later refined by Askia Muhammad after 1493, was remarkably advanced for its time:

- The territory was divided into provinces overseen by governors called fari, often chosen from the local nobility or imperial family.

- The army, structured into specialized corps (cavalry, infantry, riverine marines on the Niger), ensured internal security and protected trade caravans.

- The taxation system was rationalized to support the central state while respecting local structures.

Far from the simplistic image of a purely war-driven empire, Songhai also served as a political laboratory—where centralized authority coexisted with regional autonomy.

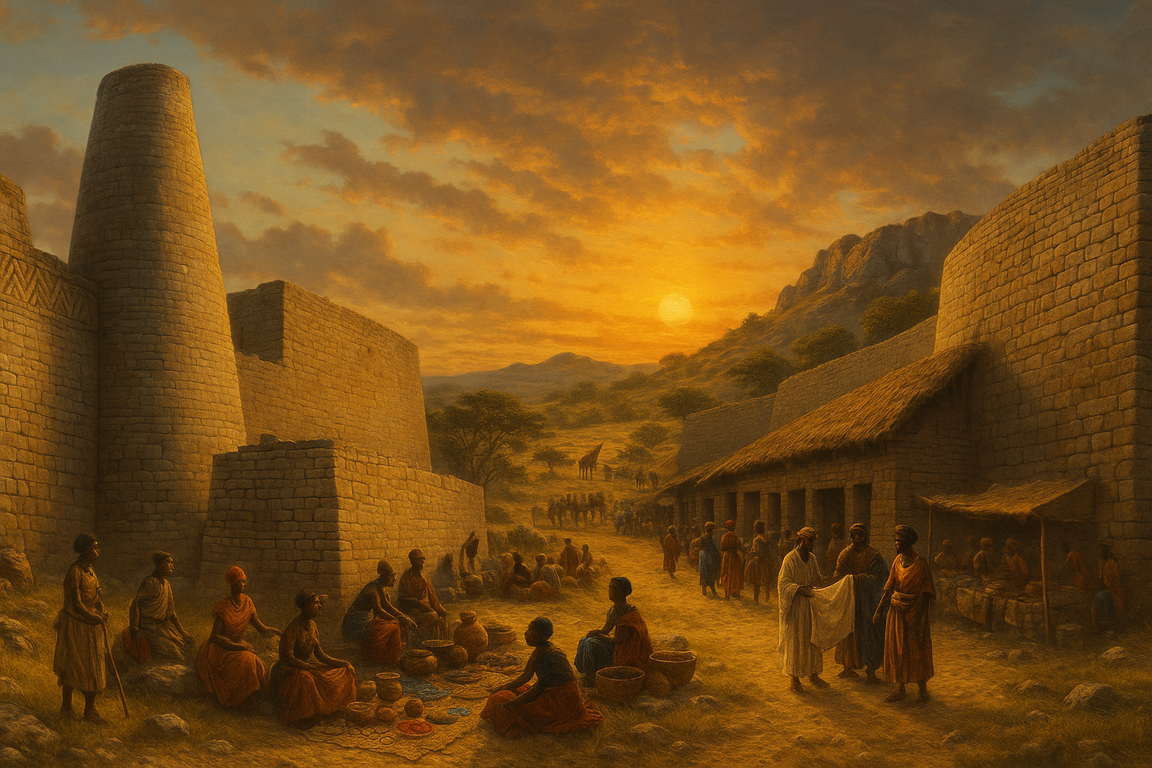

2. Great Zimbabwe: An architectural and commercial giant

While Songhai shone in the Sahel, another fascinating center of power reached its peak in the south: Great Zimbabwe.

Located in present-day Zimbabwe, this monumental complex stands as a testament to a refined civilization that developed a sophisticated urban and commercial culture between the 11th and 15th centuries.

Great Zimbabwe was not an isolated city but the heart of an extensive trade network connecting:

- Inland African gold mines,

- Swahili coastal trading cities,

- Middle Eastern and Asian markets, notably via Kilwa.

Architecturally, the site is striking for its dry-stone masonry—built without mortar—with remarkable precision and complexity:

- The Great Enclosure, an elliptical wall 250 meters in circumference, contains conical towers and labyrinthine passages.

- The Hill Complex likely served political and ritual purposes, possibly linked to kingship and spiritual authority.

Contrary to colonial notions of a non-architectural Africa, the builders of Great Zimbabwe demonstrated:

- Advanced mastery of local granite,

- Sophisticated knowledge of structural stability,

- The ability to organize large-scale collective labor.

Economically, archaeologists have uncovered within Great Zimbabwe’s ruins:

- Chinese porcelain shards,

- Persian glass beads,

- Gold objects destined for international trade.

These findings confirm that Great Zimbabwe was part of global trade networks long before European arrival on African coasts.

Politically, Great Zimbabwe likely operated under a sacral monarchy: the king (mambo) wielded both religious and temporal authority, supported by regional chiefs linked through marital and commercial alliances.

Its gradual decline in the 15th century remains partially mysterious, though it may be attributed to:

- Increasing climatic stress (drought),

- Depletion of mineral resources,

- Or the rise of eastern commercial centers like Mutapa.

3. The swahili city-states: East africa’s gateways to the Indian oceann

Along Africa’s eastern shores—from southern Somalia to modern-day Mozambique—the Swahili city-states experienced a golden age in the 15th century.

This urban mosaic, comprising cities like Kilwa, Mombasa, Sofala, Malindi, and Zanzibar, formed a thriving maritime civilization at the intersection of African, Arab, Persian, and Indian worlds.

Transoceanic trade was at the heart of this prosperity. Lateen-sailed dhows plied the Indian Ocean, following monsoon winds to trade:

- Gold from Zimbabwe,

- Ivory and rhinoceros horn,

- Precious woods,

- Spices, textiles, porcelain, and beads from India, Arabia, and even China.

Kilwa Kisiwani, in particular, became one of the wealthiest ports of its time. The famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta described Kilwa as “one of the most beautiful cities in the world.”

The city impressed with its refined urbanism:

- Coral stone palaces,

- Domed mosques,

- Multi-story houses with intricately carved doors.

Swahili culture, shaped by centuries of cross-cultural interaction, was marked by:

- The use of a Bantu language enriched with Arabic vocabulary: Kiswahili,

- The predominance of Islam as a cultural and religious foundation,

- A cosmopolitan merchant elite, adopting Arab and Persian dress, trade practices, and social norms.

Politically, the Swahili city-states operated under flexible oligarchic or monarchic systems:

- Each city was ruled by a king (sultan) assisted by councils of merchant notables.

- Autonomy was the norm: despite occasional alliances, there was no lasting political unity among the city-states.

However, this dynamism would soon face disruption with the gradual arrival of Europeans on Indian Ocean routes.

The first Portuguese expeditions—starting in 1498 with Vasco da Gama—sought to forcibly seize control of these prosperous ports, initiating a cycle of conflict and decline for these once-autonomous societies.

II. Knowledge, arts, and spiritualities

1. The Africa of Manuscripts: Codified Knowledge

The image of medieval Africa as exclusively oral remains widespread in Western imagination. However, archaeological findings, local traditions, and medieval Arabic sources show that a written culture had flourished in several African regions—particularly in the Sahel and along trans-Saharan routes.

In the 15th century, Timbuktu stood out as one of the most prominent epicenters of this intellectual effervescence.

The city housed dozens of private libraries—some founded as early as the 14th century—preserving thousands of manuscripts written in Arabic, and occasionally in African languages transcribed using Arabic script (ajami).

These manuscripts spanned a wide range of knowledge:

- Astronomy: Stellar observations, Islamic lunar calendars, navigation.

- Medicine: Herbalism, clinical diagnoses, treatment techniques, prophetic medicine.

- Islamic jurisprudence: Maliki law treatises, the basis of local social and judicial structures.

- Greek philosophy: Translations and commentaries on the works of Aristotle, Avicenna, and Averroes.

The University of Sankore, founded in the 14th century in Timbuktu, was a major institution of this intellectual radiance:

- It hosted between 10,000 and 25,000 students, according to historical estimates.

- Education followed a rigorous academic system, progressing through successive levels of mastery (comparable to bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in medieval Europe).

- Diplomas were granted following public thesis defenses in law, theology, logic, or the natural sciences.

Timbuktu’s prestige was such that scholars came from across the Islamic world:

- From the Maghreb (Fez, Tlemcen),

- From Egypt (Cairo),

- And even from al-Andalus.

The richness of Timbuktu’s manuscript heritage was only fully revealed in the second half of the 20th century. Efforts to preserve and digitize these treasures are ongoing, despite recent threats (such as the destruction by armed groups in Mali in the early 2010s).

Other centers of medieval African scholarship also thrived:

- Chinguetti (in Mauritania), with its scientific and Quranic manuscripts.

- Djenné, with its legal and commercial traditions.

- Fez, home to the University of al-Qarawiyyin, founded in 859 and considered the oldest continuously operating university in the world.

2. Complex spiritual traditions

At the end of the 15th century, Africa was far from spiritually uniform. Rather, it was a continent alive with a diversity of vibrant and dynamic religious traditions.

Islam had been spreading for centuries across North Africa, the Sahel, and as far as the Swahili coast:

- Introduced by Arab merchants and scholars since the 8th century, Islam was firmly established in the major Sahelian cities (Timbuktu, Gao, Djenné) and in Indian Ocean ports.

- By this time, Sufism exerted growing influence. Far from a rigid legalism, Sufism promoted a mystical and emotional approach to the divine—often well suited to local African societies.

- Sufi brotherhoods (notably the emerging Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya) played major roles in spreading the faith, providing religious education, and shaping social cohesion.

Christianity, on the other hand, was deeply rooted in Ethiopia—a Christian kingdom since Late Antiquity:

- Affiliated with the Coptic tradition of Alexandria, the Ethiopian Church developed a unique religious culture marked by deep sacralization of the monarch and a rich hagiographic literature (such as the Kebra Nagast).

- In the 15th century, under the reign of King Eskender (r. 1478–1494) and his successors, Ethiopia maintained intermittent diplomatic contact with Christian Europe in search of allies against Ottoman expansion.

Traditional African religions remained firmly entrenched in many regions, particularly:

- In Central Africa (Kingdoms of Kongo, Luba, Lunda),

- In West Africa’s forest belt (Yoruba and Akan kingdoms),

- In the Congo Basin.

These belief systems—often mischaracterized by European chroniclers as “paganism”—rested on:

- A complex cosmology linking the visible and invisible worlds.

- Intermediary deities (spirits, ancestors) serving as conduits between humans and a supreme creator god.

- Communal rituals involving music, dance, oral storytelling, and initiation rites, which structured both belief and social order.

These African spiritualities were not static, nor in opposition to “religions of the Book.” Instead, they often interacted with Islam or Christianity in processes of hybridization.

For instance, in Timbuktu, ancestral rites persisted alongside Islamized practices. Similarly, in Christian Ethiopia, traditional African rituals continued to influence liturgy.

3. Art: A mirror of civilizations

Far from colonial stereotypes, African art in the late 15th century reveals a refined creativity rooted in complex worldviews and remarkable technical mastery.

In West Africa, the Kingdom of Benin (in present-day Nigeria) offers one of the most striking examples:

- The royal court’s workshops produced stunning Benin bronzes, cast using the lost-wax method—mastered for centuries.

- These plaques, royal heads, and animal sculptures adorned palaces and commemorated dynastic lineages and military exploits.

- Their rich iconography fused political symbols (like the royal leopard) with cosmological themes, reflecting an elaborate conception of divine kingship (the Oba).

In the Sahel, cities like Djenné and Timbuktu developed a distinctive architectural style:

- The Djenné mosque—rebuilt in the 20th century but inheriting medieval structures—symbolizes the tradition of earthen architecture (banco).

- This architectural style, using local materials suited to the Sahelian climate, blended functionality and beauty with crenellated walls and massive, tower-like minarets.

On the Swahili coast, art also reflected a sophisticated urban culture shaped by African, Arab, and Indian influences:

- Coral stone houses, often adorned with intricately carved doors, showcased refined urban aesthetics.

- Everyday objects (ceramics, textiles, jewelry) revealed a taste for exchange and reinterpretation of foreign artistic forms.

In Christian Ethiopia, sacred art flourished in unique ways:

- The rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, carved into stone in the 12th century but still in use in 1492, represent architectural marvels.

- Ethiopian iconography—marked by hieratic faces and vibrant colors—blended Byzantine and African elements, forming a distinctly African artistic tradition.

Across all these art forms, a common thread emerges:

Art was inseparable from the spiritual and political realms.

Whether sculpting idealized images of rulers, building places of worship, or decorating merchant homes, artistic expression served a worldview where aesthetics, the sacred, and social order were deeply interwoven.

III. Resistance and internal evolutions

1. Societies Under Strain

Though Africa in 1492 shone with political, cultural, and economic diversity, it was not a static or idealized space.

Profound internal tensions were already shaping major regions of the continent, foreshadowing significant transformations in the decades to come.

In the Songhai Empire, the death of Sonni Ali Ber in 1492 triggered a period of political instability.

- His successor, Sonni Baru, was quickly challenged—particularly for his ambiguous loyalty to local animist traditions at a time when Islamization was gaining strength.

- In 1493, the ambitious and devout Muslim general Askia Muhammad overthrew Sonni Baru in a coup.

- This abrupt dynastic shift revealed the fragile balance between political power, religious legitimacy, and local allegiances.

Under Askia, Songhai would experience a new administrative and military golden age, but ethnic tensions and resistance to central authority would remain persistent issues, ultimately weakening the empire over the long term.

Along the Swahili coast, the once prosperous and autonomous city-states entered an age of uncertainty.

- The emergence of Portuguese maritime routes, beginning with Vasco da Gama’s 1498 expedition, posed a direct threat to their dominance in the gold, slave, and spice trades.

- The Portuguese, seeking control of sea routes to India, began to impose domination through force—destroying or subjugating several coastal cities like Kilwa and Mombasa.

This maritime power shift marked the end of a long period of relative economic autonomy for the Swahili cities, inaugurating centuries of colonial rivalries.

Despite these strains, 15th-century Africa remained a continent of astonishing resilience.

- African societies did not passively endure upheaval: they adapted by forming new alliances, migrating to safer territories, or restructuring political institutions.

- Their ability to absorb external shocks and reorganize social bonds was a hallmark of precolonial African dynamism.

Far from being frozen civilizations doomed to collapse, these societies demonstrated a remarkable flexibility that allowed them—at least in part—to survive both internal challenges and rising external pressures.

2. Quilombos: Seeds of black resistance

By the late 15th century, as the early Atlantic slave trade began to take shape, Africans carried with them—notwithstanding the brutality of their uprooting—deep traditions of political resistance and communal organization.

These legacies would give rise, from the first decades of the transatlantic slave trade, to forms of enforced autonomy known as quilombos: communities of fugitive slaves, primarily in Latin America, especially Brazil.

Far from being mere improvised refuges, quilombos often revived African social structures, including:

- Internal hierarchies, councils of elders, and elective or lineage-based chieftaincies;

- Agricultural, artisanal, and commercial practices rooted in African rural traditions;

- Syncretic spiritualities combining African beliefs, imposed Catholicism, and adaptations to local environments.

The most famous of these was the Quilombo of Palmares, founded in Brazil in the 17th century. It resisted Portuguese colonial assaults for nearly a century.

- At its peak, Palmares housed over 20,000 inhabitants, organized into fortified villages practicing collective agriculture and structured military defense.

- Its leader, Zumbi dos Palmares (1655–1695), likely a descendant of African military traditions, symbolized this capacity for resistance and self-determination.

The quilombo phenomenon was not merely a reaction to colonial slavery:

- It was also a reinvention of African political models on foreign soil, adapted to the needs of survival in hostile environments.

- It testified to the enduring vitality of African political cultures, capable of adaptation, reinvention, and the creation of new social orders despite adversity.

These maroon resistances foreshadowed the great struggles for freedom that would shape the history of the Americas in later centuries—from the Haitian insurrections to today’s Afro-descendant movements for cultural and political affirmation.

In 1492, while Christopher Columbus opened the Atlantic routes for Europe, Africa was writing another chapter of human history—rich, complex, and long ignored or distorted by centuries of Eurocentric narratives.

From structured empires like Songhai to the Swahili trading cities, from monumental Great Zimbabwe to the scholarly libraries of Timbuktu, Africa was then a vibrant continent engaged in the global dynamics of its time.

Yet these societies, for all their power, were not immune to internal fragilities or the profound changes brought about by violent early contacts with an expansionist Europe.

Political tensions, economic transformations, and the emergence of Atlantic trading networks would gradually upset the continent’s established balance. But they could never erase the resilience and adaptability of African civilizations.

To recognize this learned, mercantile, architectural, spiritual, and resistant Africa today is not to indulge in a romanticized reading of the past.

It is to restore the truth of a globalized history in which Africa long played a leading role—before being relegated to a colonial periphery.

By shedding light on Africa in 1492, we begin to understand that world history is not a linear, Western-centered progression, but a perpetual entanglement of cultures, exchanges, and resistances, in which the African continent held (and still holds) a vital place.

Sources

- Davidson, Basil, Africa Before the Europeans, UNESCO Publishing, 1984.

- Fage, J.D., A History of Africa, Payot Editions, 1999.

- Levtzion, Nehemia, Ancient Ghana and Mali, Methuen, 1973.

- Mazrui, Ali A., The Africans: A Triple Heritage, Little, Brown and Company, 1986.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine, Black Africa: From 1800 to the Present, Presses Universitaires de France, 1992.

- Hunwick, John O., Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sa’di’s Ta’rikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and Other Contemporary Documents, Brill, 1999.

- Monteil, Charles, A Sudanese City: Timbuktu in the 16th Century, Maisonneuve Editions, 1953.

- Vansina, Jan, Oral Tradition as History, University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Footnotes

- Christopher Columbus (1451–1506): Genoese navigator in the service of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, known for crossing the Atlantic in 1492 and initiating European colonization of the Americas.

- Songhai Empire: A vast West African state dominating the Sahel in the 15th and 16th centuries, centered on the Niger River valley and a partial successor to the Mali Empire.

- Sonni Ali Ber (r. 1464–1492): Famous ruler of the Songhai Empire, known for his military campaigns that rapidly expanded the empire and led to the conquest of Timbuktu.

- Askia Muhammad (r. 1493–1528): General turned emperor of Songhai, known for consolidating the empire and institutionalizing Islamic administration after a coup against Sonni Baru.

- Fari: Title given to provincial governors in the Songhai Empire, representatives of central imperial authority in regional territories.

- Great Zimbabwe: A major dry-stone architectural complex in present-day Zimbabwe, a testament to a powerful commercial civilization that flourished between the 11th and 15th centuries.

- Kiswahili (or Swahili): A Bantu language enriched with many Arabic influences, which became the lingua franca of East Africa, especially in the Swahili city-states.

- Qadiriyya: Sufi brotherhood founded in the 12th century in Iraq by Abdel Qadir al-Jilani, particularly influential in West Africa from the 15th century onward.

- Tijaniyya: Sufi brotherhood founded by Ahmad al-Tijani in 18th-century Algeria; while its major influence emerged in the 19th century, early Sufi influences already circulated in the 15th century.

- Kebra Nagast (“The Glory of Kings”): Foundational literary work of the Ethiopian tradition, written in Ge’ez, narrating the Solomonic lineage of Ethiopian monarchs.

- King Eskender (r. 1478–1494): Solomonic ruler of Ethiopia, whose reign was marked by internal tensions and conflict with neighboring Muslim principalities.

- Sonni Baru: Son or designated successor of Sonni Ali Ber, overthrown in 1493 by Askia Muhammad for his perceived adherence to traditional (non-Islamic) cults.

- Quilombos: Communities of fugitive African slaves primarily in colonial Brazil, which preserved elements of African political, cultural, and religious traditions.

Summary

While Columbus searched for America, Africa was writing history

I. Powerful and structured empires

- The Songhai Empire: The Apex of a Learned and Conquering Africa

- Great Zimbabwe: An Architectural and Commercial Giant

- The Swahili City-States: East Africa’s Gateways to the Indian Ocean

II. Knowledge, arts, and spiritualities

- The Africa of Manuscripts: Codified Knowledge

- Complex Spiritual Traditions

- Art as a Reflection of Civilizations

III. Resistance and internal evolutions

- Societies Under Strain

- Quilombos: Seeds of Black Resistance

Sources

Footnotes