An African American actor exiled in the Soviet Union, Wayland Rudd embodied the thwarted utopia of a life dedicated to art and equality. Caught between the Soviet myth and tragic solitude, his story raises deep questions about political exile and memory.

A black actor in the red shadow of Moscow

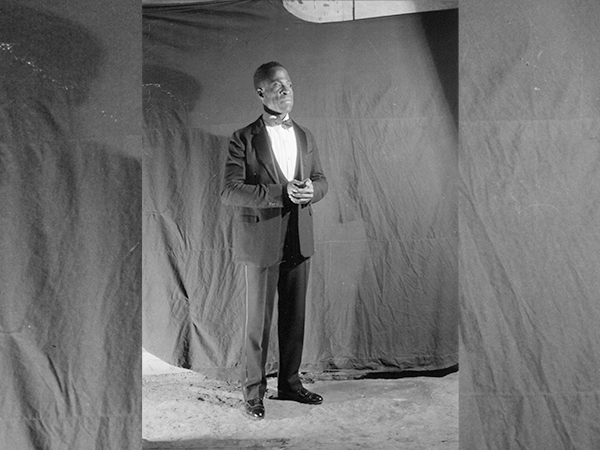

Moscow, winter 1933. In the biting cold of a film studio, a Black man, eyes alert and posture proud, steps before Lew Kuleshov’s cameras. Silence falls. The reel crackles to life. Wayland Rudd, son of America, son of everyday racism, now embodies a Soviet hero. Far from Lincoln, Nebraska, far from Broadway’s stages, he is reborn on a different stage: that of a revolution which, at least on paper, promises equality with no regard for race.

That wasn’t why he had come. Recruited with other African Americans for a film that was quickly abandoned, he could have returned home to resume his acting career, with its familiar humiliations. But Rudd chose otherwise: to stay, to become a Soviet citizen, to lend his voice to a country that—at least in theory—celebrated the brotherhood of nations.

Wayland Leonardowitsch Rudd was born in 1900 in Lincoln, Nebraska, a modest town where the American dream remained out of reach for Black children. From a young age, he realized that his future would have to be fought for against the prevailing winds of a segregated, humiliating society.

At seventeen, he left his hometown for Washington, one of the few American capitals where a Black elite was beginning to emerge. He enrolled at the prestigious Howard University, the intellectual cradle of African American movements, while working as an insurance salesman and juggling small jobs—a testament to his determination.

It was on the stage, however, that Rudd discovered his true calling. After modest beginnings in amateur troupes, he was noticed in 1929 by Jasper Deeter, founder of the Hedgerow Theater in Pennsylvania. There, in an experimental and avant-garde environment, he honed his craft as a dramatic actor. He played key roles such as The Emperor Jones by Eugene O’Neill and Othello, two emblematic parts for Black actors of the time—characters carved from pain and grandeur.

Despite a few appearances on Broadway, Rudd quickly encountered the limitations imposed on Black performers: stereotyped roles, invisibility, and rare opportunities. Like many others, he dreamed of escaping these confines. The chance came in 1932, almost by accident: a Soviet film project about racial oppression in America was recruiting some twenty African Americans. Rudd accepted without hesitation. He set sail for Moscow, expecting to stay only a few months.

The film project was quickly abandoned. But for Wayland Rudd, this trip would not be a round trip—it was a definitive departure. In the Soviet Union, he saw a radical possibility: to become an actor without chains, a free man in a country that proclaimed the brotherhood of peoples. Unlike the typical paths of African American exile (Paris, Harlem Renaissance), Rudd forged a lesser-known route: that of the Russian revolution as an improbable refuge.

After the project’s failure, he settled in Moscow and refused to let his dream of freedom collapse. Where others might have returned home, he put down roots. 1930s Soviet Russia, despite its emerging contradictions, offered him what America had denied: a stage, an audience, and recognition free from racial prerequisites.

Rudd first joined the legendary Meyerhold Theatre, a stronghold of Soviet theatrical avant-garde. Later, he continued his journey at the Stanislavski Theatre, immersing himself in the method of “experiencing the role”—radically opposed to the racial caricatures he had previously endured in American parts. His performances stood out for their gravity and sincerity; he was no longer the exotic token or tolerated exception, but an actor among others, judged solely on his talent.

His hunger for knowledge led him to enroll at GITIS (the State Institute of Dramatic Art), in the prestigious directing department. In Moscow, Rudd was not content to perform—he thought, he wrote. Among his works was Andy Jones, a play inspired by the life of Angelo Herndon, a Black American communist arrested for organizing a march of unemployed Black and white workers in the segregated South. Rudd saw in this figure a perfect synthesis of his commitment: art, politics, and the fight for equality.

The Soviet press, eager for icons that could embody proletarian internationalism, sometimes held him up as the symbol of the “free Black man” under socialism. Yet behind this ideological showcase, his day-to-day life remained that of a foreigner: appreciated but instrumentalized, admired but also isolated.

In his Soviet years, Wayland Rudd embodied a poignant contradiction: both actor and activist, living myth and solitary pioneer, lost in a utopia already beginning to crack.

In 1933, Wayland Rudd made his Soviet film debut in The Great Consoler (Velikiy Uteshitel) directed by Lew Kuleshov, a master of montage cinema. The film, inspired by the life of O. Henry, celebrated compassion and rebellion against social injustice. Rudd portrayed a Black inmate—a figure of silent dignity in the face of oppression—in a resolutely Marxist reading of racial inequality.

This role was foundational: in the Soviet Union of that era, where cinema was both propaganda and popular art, Wayland Rudd became a living image of proletarian internationalism. A talented Black American actor who chose the homeland of socialism—a statement both political and artistic.

More films followed, though more modest in scope: he appeared in a Soviet adaptation of Tom Sawyer (1936), then in Captain at Fifteen (1945), and in The Life of Miklouho-Maclay (1947). Each of his appearances was carefully framed: he was shown as a loyal companion, a friend of the Soviet people, an idealized image of a Black man freed from the chains of American capitalism.

But behind this public image, reality was more complex. Roles remained scarce, often secondary. World War II and the rise of Stalinism tightened artistic expression, especially for foreigners. Even in a society that claimed to be antiracist, Wayland Rudd felt the invisible walls keeping him at the margins.

On screen, he had become a fixed symbol—an icon both useful and, gradually, forgotten. The original dream—to be a fully recognized actor—dissolved in the political necessities of a time when art first and foremost had to serve the cause.

Wayland Rudd thus experienced the paradox of many ideological exiles: recognized for what he represented more than for who he was; honored, yet marginalized; free, but under conditions.

By the late 1940s, Wayland Rudd had become a discreet figure in the Soviet cultural landscape. The times had changed. The USSR, once hungry for international icons, was turning inward. The Stalinist climate grew suffocating, even for those who had once seen socialism as a final refuge.

For Rudd, roles became increasingly rare, artistic opportunities dwindled. He continued to write and work occasionally, but his name slowly faded from public memory. His original, sincere commitment was now eclipsed by a new cultural policy increasingly suspicious of foreign influence—even ideologically aligned ones.

On a personal level, fatigue and illness took their toll. A simple case of appendicitis, left untreated, ended his life suddenly in 1952, in Moscow. He was only fifty-two.

His death went almost unnoticed. No major official tributes, no triumphant retrospectives. His son, Wayland Rudd Jr., still a child, would go on to live a quiet life in the Soviet Union—far from the spotlight that had once shone on his father.

Wayland Rudd thus died as he lived: between light and obscurity, between ideological exaltation and final solitude. His story is that of a man who bet everything on a foreign utopia—and who, in the end, never stopped being a foreigner.

Summary

A Black Actor in the Red Shadow of Moscow