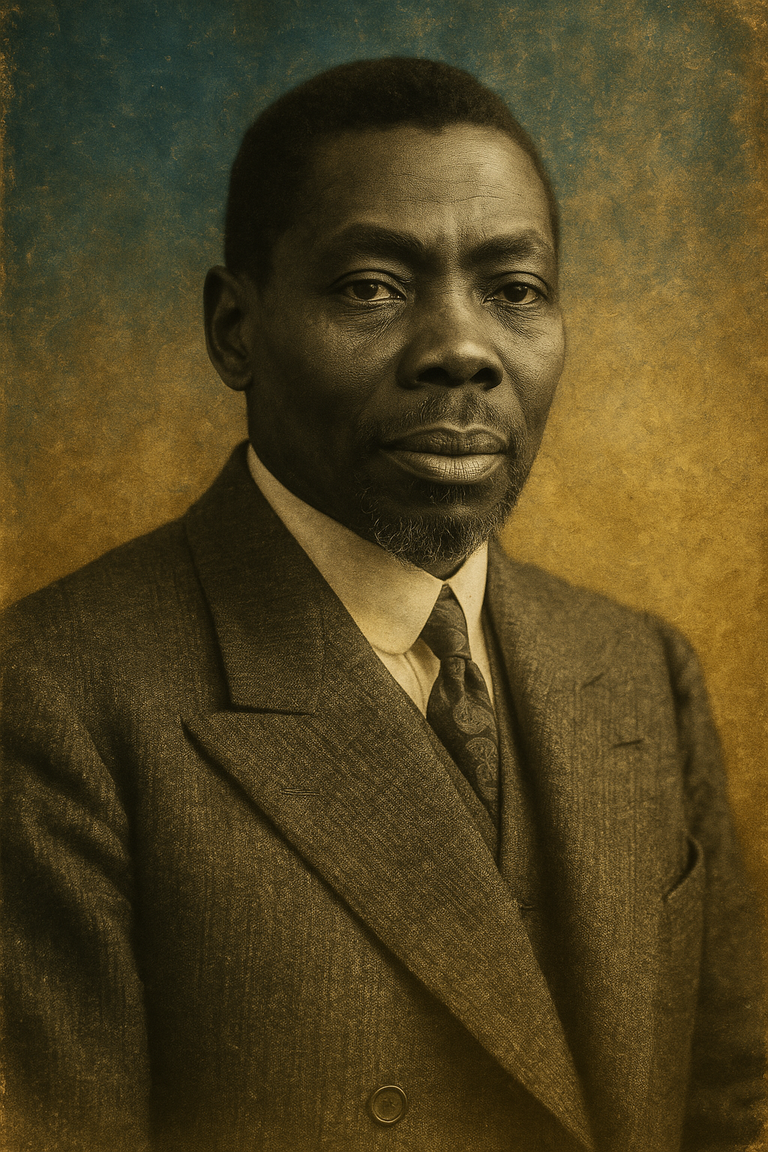

The first Black African elected as a deputy in France, Blaise Diagne carried the hopes of republican equality at the heart of the colonial empire. His journey—between political conquest and historical ambiguity—still challenges France’s memory and its unfulfilled promises.

The Blaise Diagne paradox

On the island of Gorée, swept by Atlantic winds, a young boy climbed the steps of a modest missionary school in 1884. His birth name, Galaye M’Baye Diagne, would soon be erased and replaced with a Catholic first name: Blaise. In that moment, in the carefree days of childhood, he had no idea his fate would unfold far from African shores.

Later, dressed in his model student’s uniform, he would receive an award for excellence in Saint-Louis, under the approving gaze of his colonial teachers. An apparently modest distinction, but one that, in a brutally colonized Africa, marked a first step toward the unimaginable: to sit, as a Black man, at the heart of White power.

Blaise Diagne, the first Black African deputy in the French Chamber of Deputies, became a symbol of an ascent the Republic claimed to offer—yet in reality, still reserved for a chosen few.

What remains today of these hybrid trajectories? Of these men who, believing in French universalism, were often caught in the Empire’s double game? What do they reveal about the dream of assimilation, the pursuit of rights, and the cost of silence and fractured memory?

Through the complex figure of Blaise Diagne emerges a broader reflection on loyalty, recognition, and erasure—questions that still resonate a century later.

From a colonial Island to the benches of the republic

Born on October 13, 1872, on the island of Gorée¹—historically a hub of the slave trade and later a laboratory for French assimilation—Galaye M’Baye Diagne (the future Blaise Diagne) grew up between two worlds. That of African traditions, passed down by his Lébou and Manjack parents, and that of colonial schooling, missionaries, and French education as the sole path to success.

Early on, his adoption by the mixed-race Crespin family of Saint-Louis lifted him from the typical fate of fishermen’s sons. Renamed “Blaise” by the Brothers of Ploërmel², he received a methodical education steeped in republican morals as much as colonial prejudices. The young Blaise excelled: he learned to read, write, and master rhetoric with rare ease. At award ceremonies, his name echoed the civilizing slogans of the era.

A recipient of a French government scholarship, he left Senegal to study in Aix-en-Provence. There, far from the benevolent eyes of Gorée, he discovered another side of the Republic—one that preached universal equality while relegating Black bodies to the margins, both in classrooms and in the streets.

Weakened by health issues, Diagne interrupted his studies and returned to Africa. But he did not fade into obscurity. In 1891, he passed the customs officer exam with flying colors—a prestigious career path for the few Africans allowed access to positions of authority within the colonial administration.

His first postings took him to Dahomey, then to French Congo, Réunion, and finally Madagascar. Everywhere, he rigorously enforced the laws of an Empire he aimed to show could offer real equality. Through his trajectory, Blaise Diagne embodied a sincere yet already ambiguous dream of fusion between France and its colonies.

Being a “model assimilé³” earned him promotions but also isolated him from those in Africa who were beginning to denounce the brutality of the colonial system. History was moving forward, and Diagne marched with it—still convinced that a Black man could earn respect and influence from within the institutions themselves.

The civil servant turned political voice

In 1914, as Europe plunged into war, Blaise Diagne crossed a historic threshold. By winning the legislative election in Senegal, he became the first Black African elected to the French Chamber of Deputies. This was not merely a personal victory; it was a major political event. Until then, only a few métis or assimilated notables had held public office under the Republic. With Diagne, an “unmixed African,” as some condescendingly put it, entered the Palais Bourbon.

Nicknamed “the voice of Africa,” Blaise Diagne asserted his stature in an Assembly often reluctant to accept a Black man in its ranks. From his first speeches, he demanded full and equal citizenship for the inhabitants of the “Four Communes” (Dakar, Gorée, Saint-Louis, and Rufisque). No more exceptional status, no more being “French on occasion” depending on colonial needs.

In 1916, thanks to his political skill, Diagne achieved a major success: the passage of a law granting French citizenship to residents of the Four Communes without requiring them to renounce their personal status. It was a subtle compromise between republican assimilation and the recognition of African specificities—an outstanding victory in a deeply racialized context.

In the Assembly, Diagne was not just an orator but a strategist. Aligning with the Republican-Socialists and later with the Independents, he maneuvered pragmatically among political groups, supported by Freemasonry—a discreet but powerful network that opened doors his skin color would otherwise have kept closed.

Yet behind the official applause, suspicion lingered. His opponents alternately accused him of excessive loyalty to Paris or of secretly encouraging indigenous demands. Diagne walked a dangerous tightrope: he had to prove himself “French enough” to sit in Parliament, but also “African enough” to speak for his people.

At every session, in every speech, Blaise Diagne moved along a tightrope stretched between recognition and instrumentalization. His election, his actions, his public image—all already bore the seeds of the ambiguity that would later surround his legacy.

Blaise Diagne and the black troops

As World War I dragged on in the mud and blood of the trenches, imperial France turned to its colonies. The need for soldiers was urgent. In 1918, Georges Clemenceau appointed Blaise Diagne as High Commissioner for Indigenous Recruitment—a new role that granted him considerable power, but also heavy responsibility.

In towns and villages across French West Africa, Diagne embarked on an unprecedented tour. With impassioned speeches, he promised citizenship, recognition, the honor of defending the “motherland.” He persuaded, negotiated, and sometimes implored. Young men, drawn by promises of equality or pushed by social pressure, enlisted en masse. Thanks to his efforts, over 63,000 soldiers were recruited in French West Africa⁴ and 14,000 in French Equatorial Africa.

Yet the success was morally ambiguous. Behind the rhetoric of dignity, the reality at the front was harsh. Senegalese riflemen were often sent to the front lines, exposed to the worst conditions and the deadliest assaults, with the high command showing a sometimes cynical indifference. Diagne himself, speaking in Parliament in 1917, denounced the inhumanity with which Black troops were used: “they were subjected to a true massacre, sadly useless,” he declared with restrained emotion.

The recruitment campaign’s success did not erase the moral complexity of his mission. In exchange for the blood shed, Diagne secured a historic law: the formal recognition of French citizenship for the natives of the Four Communes. A legal victory—but won at the cost of a painful pact, where political loyalty and military sacrifice were inextricably linked.

For many, Blaise Diagne represented the figure of the mediator—one who opened doors while bearing the contradictions of colonial rule. He would remain marked by this complex role: celebrated by some as a liberator, criticized by others as a facilitator of imperial compromise.

The twilight of a wounded loyalty

As the years passed, the shine of Blaise Diagne began to fade. Though his political career remained intact (mayor of Dakar, deputy reelected without interruption), the world around him was changing. Colonial Africa was abuzz with new voices—more radical, more impatient. A generation of militants, often Marxist or nationalist, now condemned assimilation as a trap, and Diagne’s loyalty to the French Republic as a betrayal.

Former African supporters criticized him for refusing to challenge the colonial order. For them, gaining rights within the imperial framework was no longer enough—it was the system itself that had to be dismantled. In this boiling context, Blaise Diagne increasingly appeared as a man of the past: loyal to a Republic that proclaimed equality while obstructing it, devoted to an ideal history was tearing apart.

Personally, Diagne also suffered. Weakened by years of parliamentary battles and afflicted with tuberculosis (contracted in Paris’s cold), he continued to fulfill his duties, still faithful to the idea that integration into the French Republic was both possible and desirable.

In 1931, he briefly became Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies in Laval’s government—the first time an African held such a position. Yet despite its prestige, this title hid the truth: his influence was minimal, his power symbolic at best. Diagne had become a token figure rather than a true decision-maker.

On May 11, 1934, Blaise Diagne died in Cambo-les-Bains⁵. His body was soon repatriated to Dakar, where the population paid heartfelt tribute. Yet in France’s official history, his memory was already fading—buried beneath the triumphant narratives of Empire, which struggled to celebrate a Black pioneer who had dared believe in the Republic’s promises.

Thus ended the journey of a man who had always walked a precarious line—between loyalty to ideals and disillusionment with the realities of power.

A divided memory of an african pioneer

After his death, Blaise Diagne entered a strange legacy—torn between local celebration and national oblivion. In Senegal, his name lives on in collective memory: avenues, schools, and the airport bear the mark of the first African to sit in the French Republic. Busts erected on his native island of Gorée commemorate his uniqueness and remarkable ascent.

But in France, his memory is more ambivalent—almost awkward. In the official accounts of the Third Republic, he is often reduced to a historical curiosity: a “success story” of assimilation, soon overshadowed by metropolitan figures. Rarely recognized as a major political actor, he remains on the margins of a national history that still struggles to include its overseas children in its foundational narrative.

Among 20th-century historians and anti-colonial activists, opinions were also mixed, sometimes harsh. Some viewed Diagne as a loyal agent of colonialism, trading theoretical equality for practical silence on oppression. Others saw him as emblematic of the era’s complexities: a man who sincerely believed in the Republic’s promises and who, as best he could, won victories for his compatriots.

His legacy—profoundly ambivalent—thus reflects the tensions of his time: between hopes of integration and the reality of exclusion, between individual promotion and structural stagnation.

Through Blaise Diagne, we confront the difficulty of evaluating pioneering figures: how to judge those who broke barriers in a hostile world, but at the cost of compromises too significant to ignore?

Today, as France increasingly confronts its colonial past, the figure of Blaise Diagne invites not hasty judgment, but a broader reflection on broken promises, silent struggles, and reconstructed memories.

Sources

- Dominique Chathuant, L’émergence d’une élite politique noire dans la France du premier 20ᵉ siècle ?, Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’Histoire, no. 101, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009.

- Iba Der Thiam, La révolution de 1914 au Sénégal : l’élection de Blaise Diagne, L’Harmattan Sénégal, 2014.

- Bruno Fuligni, Le retour de Blaise Diagne, Humanisme, Grand Orient de France, no. 304, 2014.

- Chantal Antier-Renaud, Les soldats des colonies dans la Première Guerre mondiale, Éditions Ouest-France, 2008.

- Roger Little, Du nouveau sur le procès Blaise Diagne – René Maran, Cahiers d’études africaines, no. 237, 2020.

Notes

- Gorée Island, off the coast of Dakar (Senegal), was a major colonial trading post and center of the slave trade from the 15th to 19th centuries. By the 19th century, it had become a symbol of French presence in West Africa.

- The Brothers of Ploërmel, or Brothers of Christian Instruction of Ploërmel, are a Catholic religious order founded in 1824 in Brittany, engaged in educating young boys, particularly in the French colonies.

- In the French colonial context, an “assimilé” referred to an indigenous person who had adopted French legal, cultural, and political norms, theoretically enjoying civic rights similar to metropolitan citizens, though still facing racial discrimination.

- French West Africa (AOF) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in Sub-Saharan Africa, created in 1895. It included Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, French Sudan (Mali), and Guinea, among others. It was dissolved in 1958 before African independence.

- Cambo-les-Bains, a small spa town in southwestern France, was renowned in the early 20th century for treating respiratory illnesses such as tuberculosis.

Table of Contents

- The Blaise Diagne Paradox

- From a Colonial Island to the Benches of the Republic

- The Civil Servant Turned Political Voice

- Blaise Diagne and the Black Troops

- The Twilight of a Wounded Loyalty

- A Divided Memory of an African Pioneer

- Sources

- Notes