A large part of the people of Réunion today have African origins. This article offers a historical overview of that presence.

Before slavery

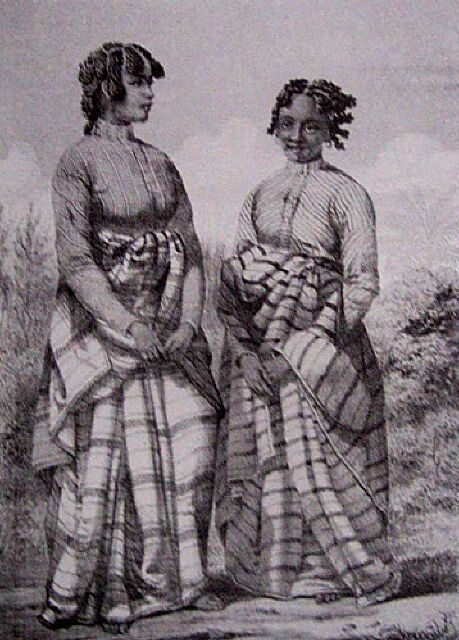

The aptly named island of Réunion is located at the crossroads of Africa and Asia. The diversity of the populations that have settled there over the centuries reflects this geographical position. While Arab and probably also Indonesian navigators had very early knowledge of the island, the first “recent” and permanent presence of Africans on Réunion is attested in 1663. During that year, ten Malagasy servants accompanied two Frenchmen who came to settle voluntarily on the island. This presence of Malagasy people intensified in the following decades, notably with the deportation of Malagasy women intended to “offset” the imbalance between the large number of white men and the absence of white women. Women from the Indo-Portuguese coast were also deported for this purpose.

During slavery

In 1690, slavery officially began on Réunion. Within the framework of the flourishing cultivation of coffee in the first half of the 18th century, slaves originating from Madagascar were deported to the island. This period also saw the beginnings of continental African presence with the deportation of populations from southeastern Africa, notably from the north of what is now Mozambique and, later, from Zanzibar. Soon, the imbalance between continental Africans and Malagasy became noticeable, with estimates suggesting five continental Africans for every one Malagasy deported and enslaved.

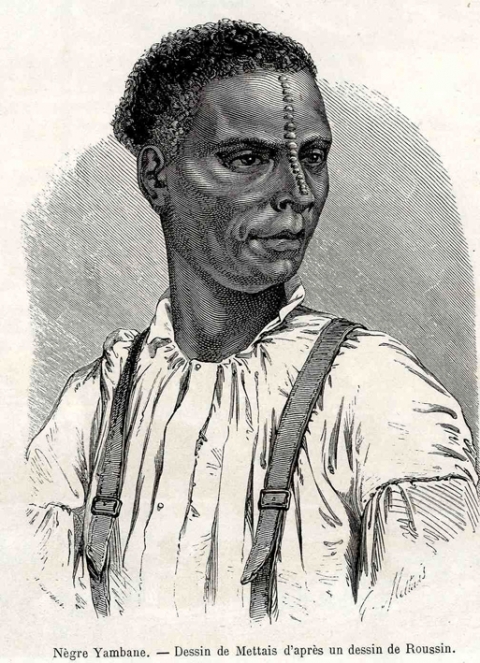

Still during the 18th century, another African population, geographically more distant, lived alongside the slaves from southeastern Africa and Madagascar. Faced with attempts by the latter to flee back to their homeland in pirogues, the colonists sought to bring in slaves originating from much more distant regions of West Africa. At the same time, men and women from Madagascar and the southeastern African coast were deported to the American continent. In 1704, a census thus records that out of 209 foreign-born slaves, 10 came from what was called “Guinea,” that is to say West Africa, as well as one “Moor,” compared for example with 110 from Madagascar. References to specific West African ethnic groups are sometimes made, as in the case of the Yolofs (= Wolofs of Senegambia).

This recourse to West Africans, which intensified between 1729 and 1735, would nonetheless never reach the same proportion as that of East Africans or even Indians. Indeed, the costs and human losses caused by these long voyages were not very profitable for the colonists.

From the beginning of the second half of the 18th century, the island’s economy came to rely on sugar cultivation because of the destruction of coffee plants by an aphid. The predominance of East African slaves compared with Malagasy slaves was considerably reduced and, in 1808, out of 54,000 slaves, the former are estimated at 17,476 and the latter at 11,547, the majority of the remainder being made up of slaves born locally of often diverse African origins, and called “Creoles.”

After slavery

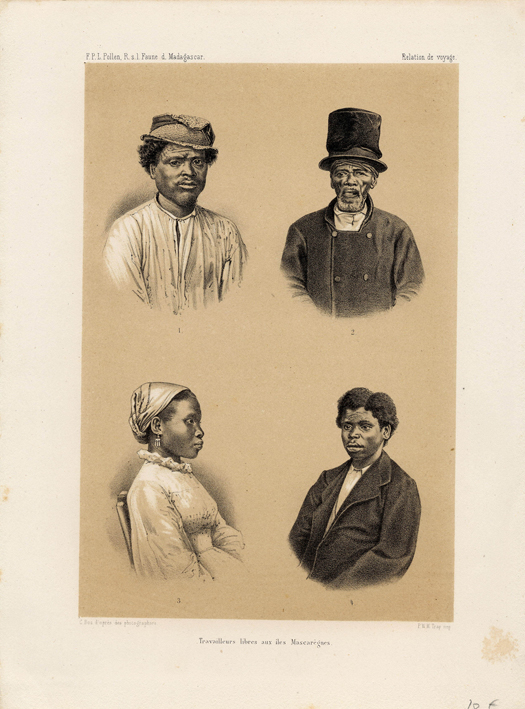

After the abolition of slavery in 1848, the colonists turned to another form of labor. This was the engagisme, a kind of more or less disguised slavery through labor contracts. Although it mainly involved populations from India, about 30,000 Africans from the continent, Madagascar, the Comoros, Mozambique, Somalia, or the neighboring island of Rodrigues migrated to Réunion under this system. Although their contracts were limited to a few years, some of them in fact remained after they ended.

After colonization, Malagasy people continued to come and settle in Réunion, benefiting from French nationality that was granted to them by virtue of their birth during the colonial period.

The same was true for Comorians and Mahorans. Since the early 2000s, natives of Mayotte, also of French nationality, have come to swell the ranks of this majority of Réunion inhabitants of African descent.

Although they are often the target of xenophobic discourse based on the rhetoric of invasion, notably because of their Muslim religion, Mahoran immigration to Réunion remains marginal, according to recent studies.

References

Jacqueline Andoche, Laurent Hoarau, Jean-François Rebeyrotte and Emmanuel Souffrin / La Réunion, Le traitement de l’étranger en situation pluriculturelle : la catégorisation statistique à l’épreuve des classifications populaires

Jean Barbier / Le musée de Villèle à La Réunion entre histoire et mémoire de l’esclavage. Un haut lieu de l’histoire sociale réunionnaise

Jean-François Géraud / L’Afrique des sucriers