She sang for Haiti, for Africa, for memory. Actress, activist, and priestess of the spoken word, Toto Bissainthe traversed exile and silence to give voice to the voiceless. From the theater stage to recording studios, she wove together Negritude, spirituality, and resistance in a powerful, unclassifiable body of work. This is the incandescent journey of a woman who never ceased to speak truth, sing justice, and dream of unity.

Singing to avoid silence

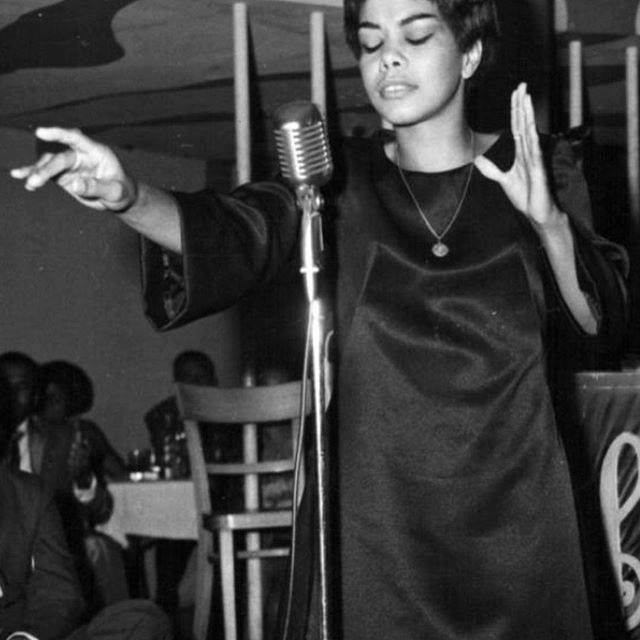

Paris, 1973. In the small, intimate venue La Vieille Grille, a woman steps forward, alone. A simple dress, a drum at her side. No décor, no artifice. Just a voice. A voice from Haiti, burdened with memory, pain, and revolt. A voice that doesn’t merely sing: it summons the ancestors, mourns a people, chants resistance. That night, the audience discovers Toto Bissainthe. And for many, nothing would ever be the same.

But who still remembers Toto Bissainthe?

In the broader narrative of Negritude, protest music, and Black art in exile, her name is too often absent. As if her voice—etched on records, stages, and memories—never truly found its place in history. As if exile erased even those who bore it as a banner.

Toto Bissainthe didn’t merely sing about Haiti. She embodied exile as a source of creation. She gave sonic shape to the silence of oppression. Actress, poet, singer—she was all of these, yet always in service of a single cause: Black dignity. In the face of Duvalier’s dictatorship, French indifference, and cultural industry scorn, she held her line: to sing was not to be silent. To sing was to awaken.

This biographical fresco is not merely the story of a career. It’s the restoration of a presence. A voice—Black, diasporic, Creole, defiant. A voice that said no when it had to be said. And one that, even today, still speaks of one thing: the necessity of remembering.

Cap-Haïtien, the call of the drum

Some voices are born in the comfort of velvet salons. Others in the clash of history. Toto Bissainthe’s voice was born somewhere between the two: in a Cap-Haïtien home that loved the arts, in a country fractured by injustice. Haiti, the tormented cradle of unfinished revolutions, where songs are always partly stifled cries.

Born in April 1934, Marie-Clotilde Bissainthe—later nicknamed “Toto”—grew up in an atmosphere of intellectuals, colonial ghosts, and broken dreams. Her childhood was steeped in tales, popular music, political tension—and, above all, in that syncretic Haitian culture where the Vodou drum is always near, even when it doesn’t sound.

Early on, she understood that body and voice could be weapons. She left for France to study dramatic arts but carried with her far more than a Creole accent or a few scores. She carried Haiti. Not the postcard image, not the tourist folklore—but that living, insurgent, wounded Haiti that only the diaspora can evoke with such truth.

In Paris, she was Black. In Haiti, she was exiled. This double uprooting became her engine. It nourished her artistic choices, her search for identity, her polyphonic song. She didn’t seek a career. She sought a cry.

And that cry, she turned into song.

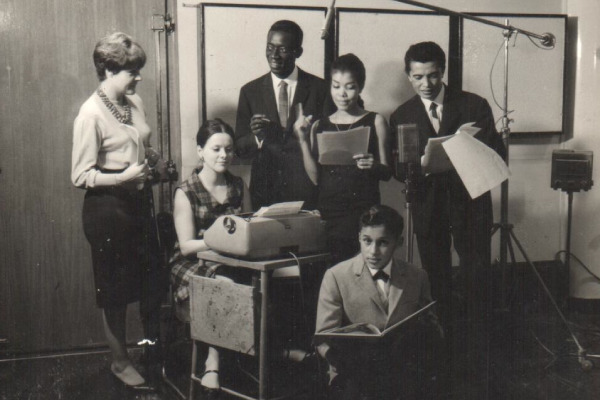

Theater as a cradle of negritude (Les Griots, Genet, Beckett)

In Paris, Toto Bissainthe didn’t just learn—she created. In 1956, she co-founded the troupe Les Griots, the first Black theater company in France, alongside Roger Blin and other Afro-descendant intellectuals. In a country still dulled by colonial illusions, this was a radical break. Les Griots did not seek assimilation; they sought reclamation. Onstage, they recited, denounced, invoked. Theater became ritual. Text became drum. The stage, a battleground.

Even the troupe’s name was a manifesto: griot, the West African word for the keeper of memory, the storyteller, the oral resistor. With that name, Bissainthe rooted her art in a tradition of Black speech freed from white norms. She did not act—she evoked. She did not recite—she embodied.

The troupe’s dramaturgical choices were bold. Performing Jean Genet’s The Blacks in 1959—post-colonial France still haunted by the Algerian War—meant placing Black voices at the heart of Western theater, only to subvert it. With Genet, the grotesque gaze of whiteness was turned back on itself. With Beckett, whom she encountered, it was the absurd void of existence that she inhabited with Creole sorrow. In this theater of shadows and cries, she learned to stand with the strength of the defeated.

What Toto sought was not a place in the spotlight, but a space to speak. To speak Haiti. To speak exile. To speak Africa, through the body of a Black woman who refused to be a mere ornament in someone else’s play.

Les Griots laid the foundation for a diasporic, committed, embodied theater. And Bissainthe, with her raw voice and magnetic presence, already inscribed the first notes of what would become a revolutionary song.

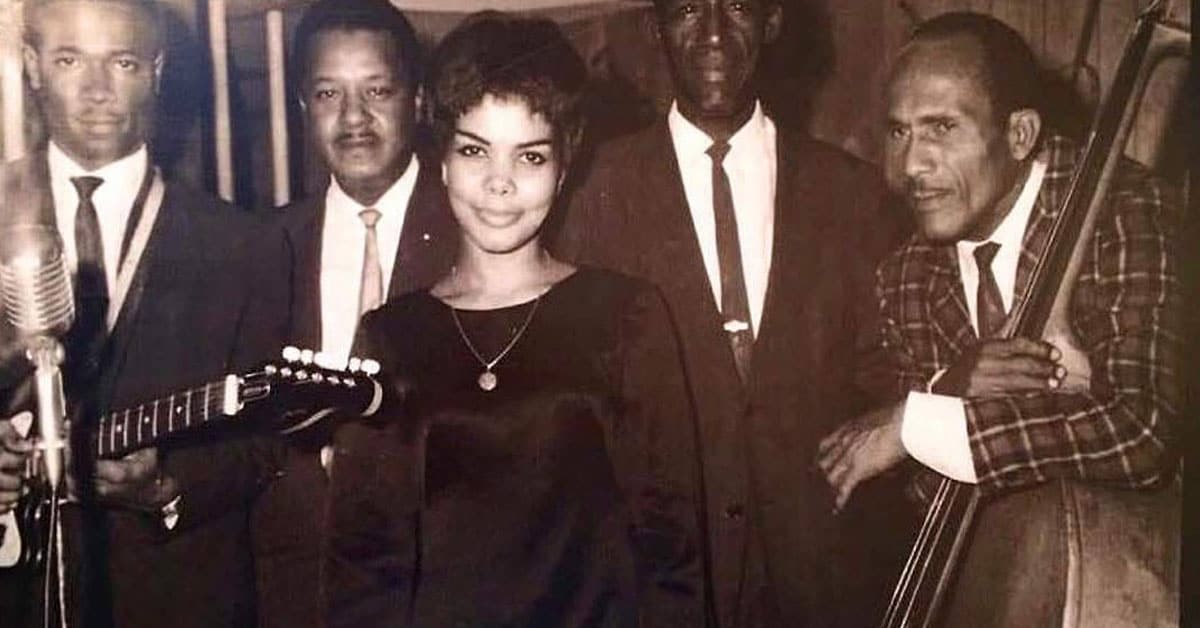

The call of song: A voice for exile and memory

In the early 1970s, one evening at La Vieille Grille, a woman entered in silence. She didn’t speak—she sang. And suddenly, the pain of a people passed through the throat of one. Toto Bissainthe did not become a singer—she became a modern griot. A medium. A conjurer.

Her singing was not melody—it was lament. It was a call. She didn’t perform—she summoned. The ancestors responded. Invisible drums echoed in Creole. In every syllable, you could hear chains, fields, stolen laughter, houngans, prayers, hoes, anger.

Her music was no exotic flair. It pulsed with the memory of marronage, of uprising, of exile. She wove together Africa, peasant Haiti, Parisian wanderings. It was a Black Caribbean blues, each note bearing mourning and struggle. Her albums (Toto à New York, Toto chante Haïti, Coda) were scores for mourning the land and reviving dignity.

Bissainthe revived rural laments, reinvented Vodou rituals, dared the nakedness of voice to speak the silences of the oppressed. Her voice was revolutionary not because it screamed, but because it wept. And that weeping became political. She said:

“I sing for Black people. Because it’s necessary. Because we are scattered. And we must call out.”

In a world dominated by Western standards, she chose Creole orality. Against colonial music industries, she countered with the sacred drum. Against organized amnesia, she opposed song as emotional archive.

Toto didn’t seek success. She sought resonance—the kind that crosses oceans and centuries. The kind that links Césaire to Fanon, Dessalines to Malcolm, the mornes to Harlem. The kind that turns a single song into a world-spanning statement.

An activist against dictatorships

Toto Bissainthe never sang to please. She sang to disturb. To awaken. To crack open certainties and state-sanctioned silence. In an era where dissenting voices were silenced, she turned hers into a weapon. A gentle one—but sharp. An intimate one—but deeply political.

Under Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime, she could only return to Haiti under strict conditions. Not to embrace her mother or hold her children—but to sing once, in a controlled setting. The dictator tolerated French (the language of elites, of denial), but feared Creole—the language of the people, of unity, of potential rebellion. As she bitterly noted:

“In Creole, they silence me. In French, they let me speak.”

In her Parisian and New York concerts, Toto denounced without hesitation: forced exile, confiscated land, orchestrated poverty. She evoked the disappeared, the bodies thrown into ravines, the sobs muffled behind closed doors. She sang of struggle and sorrow, beauty and oppression. She became the voice of the voiceless. A conscience in exile.

In Paris, she moved among Antillean, Pan-African, and Negritude circles but refused to be boxed into any one current. She was independent. Unclassifiable. She sang for justice, not ideology. Her fight went beyond Haiti. It was for all Black peoples—colonized, scattered, broken by dictatorship and postcolonial dependence.

When she finally returned to Haiti in 1986, after Duvalier’s fall, it was with wild hope to help rebuild a nation ravaged by terror. But disillusion came quickly. Political rivalries, betrayals, and persistent poverty drained her energy. The artist in her survived—but the activist bled.

Her final concerts were veiled farewells. She still spoke of justice, reconciliation, Koumbit (that ancestral Haitian solidarity)—but her eyes shone with deep fatigue. As if she sensed her voice would soon go silent. But not her struggle.

Because Toto Bissainthe was more than an exile singer. She was living memory. A fighter. A heart-driven activist.

Between forgetting and reclaiming

Toto Bissainthe died twice. Once physically, on June 4, 1994, from cirrhosis. And once more, slowly, in the silence of cultural institutions that too often chose to forget her rather than celebrate her. The child of Cap-Haïtien, who sang Haiti to the point of exhaustion, receives only sporadic homage. No national monument. Few mentions in school curricula. Barely a handful of articles in mainstream media.

Why such amnesia? Because Bissainthe could not be co-opted. She fit no mold. Too Black for conservatives, too revolutionary for moderates, too free for politicians, too mystical for rationalists. She eluded categorization. And in an age that only honors sanitized figures, she disturbed.

And yet, in recent years, a new wave of reclaiming has emerged. Some documentarians are rediscovering her. Caribbean artists cite her as a major influence. On YouTube, her tracks resurface. Creole students raise her name in protests against systemic racism. She’s coming back—not as a sanitized icon, but as a source. A matrix.

But this rediscovery raises another question: how do we speak of her without betraying her? How do we honor her memory without folklorizing it? How do we make her songs resonate without erasing the pain?

Because Toto did not sing to please. She sang to pass something on—a message, a rage, a faith. Her art was political, never partisan. Spiritual, never dogmatic. She believed in the power of voice to heal the wounds of history. And that voice deserves more than a fleeting revival. It deserves full, complete, demanding recognition.

What we owe Toto Bissainthe

Toto Bissainthe didn’t just sing Haiti—she shaped it. Like an invisible hand sculpting suffering clay, she passed on to future generations an art of speaking, remembering, resisting. Her work opened a path for a lineage of Caribbean, African, and diasporic creators for whom memory is not nostalgia, but a weapon.

Today, her echo lives on in voices like Emeline Michel, Mélissa Laveaux, Leyla McCalla, or Moonlight Benjamin. Each, in their own way, carries the torch—of a rooted, engaged, decidedly decolonial music. The drums she awakened in the 1970s still beat—sometimes even louder.

Among activist circles, Toto Bissainthe is now cited alongside Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, and Édouard Glissant. Not as just a singer—but as an intellectual in exile, a thinker of the Black body, diasporic memory, and colonial trauma.

In schools, unfortunately, her name is still too often absent. Her songs rarely appear in curricula. In museums, her face remains in shadow. And yet, anyone who seeks to understand the Caribbean’s contemporary cry, Haiti’s fractured identity, or the links between spirituality and revolt—must one day engage with her work.

Her legacy is alive. It calls us to listen differently. To hear what rises from below, what trembles, what fights. It calls us to find dignity in song. To honor memory through art. And to understand that all true creation is a promise: that silence must never win.

Sources

Claude-Narcisse, Jasmine, Mémoire de femmes, Port-au-Prince, UNICEF Haiti, 1997, pp. 153–159.

Slaheddine, Haddad, Littératures francophones des Caraïbes, Paris, Karthala, 2004.

Weiss, Jason, “French-Caribbean Music: An Introduction,” Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, vol. 32, no. 58, 1999, pp. 75–76.

Guilbault, Jocelyne, Zouk: World Music in the West Indies, University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Maldoror, Sarah, Toto Bissainthe (documentary film, 1984, 5 min).

AlterPresse, Le souvenir de Toto Bissainthe, interprète révoltée, June 7, 2015.

Totobissainthe.com, official website, consulted June 2025.

Raoul Peck, L’homme sur les quais (film, 1993).

Catala, J.C., “Je chante l’histoire du peuple noir,” La Vie Ouvrière, October 29, 1980.

Toto Bissainthe, Toto chante Haïti, Arion, 1977.

Summary

- Singing to Avoid Silence

- Cap-Haïtien, the Call of the Drum

- Theater as a Cradle of Negritude (Les Griots, Genet, Beckett)

- The Call of Song: A Voice for Exile and Memory

- An Activist Against Dictatorships

- Between Forgetting and Reclaiming

- What We Owe Toto Bissainthe

- Sources