Jean-Claude Duvalier, heir to a throne built on fear, did not govern—he prolonged the shadow. From his teenage rise to power to his gilded exile, his reign embodies the morbid transformation of a postcolonial power (Black, authoritarian, and corrupt) that commodified a people’s misery. This story of an inherited dictatorship questions Haitian memory and the persistent silences of justice.

Inheriting silence, ruling over cries

Jean-Claude Duvalier was born in a house where even the walls held their breath. They said his father spoke to the dead, that his words made the living tremble. He was born with a name already heavy with history, dread, and blood. In a country forged by the promise of freedom—a promise snatched from white hands by Black fists—he became, at nineteen, the youngest head of state in the world. Not a revolutionary. A son. An heir. He did not choose power. He became its mask.

Haiti was not lacking in beauty. It overflowed with it. From hills to sea, from Creole voices to Vodou drums, the country sang, wept, survived. But this beauty was too often stifled beneath the boot of men who looked like the people in skin but not in soul. The paradox of Black power over a Black people still haunts the collective conscience. What does it mean to be a tyrant in a land of the freed? How can the blood of ancestors, shed for dignity, nourish a regime rooted in fear?

Jean-Claude Duvalier was neither absolute darkness nor light. He inhabited that murky zone where choices become learned gestures, where the comfort of silence turns into complicity. Behind his frozen smile, a whole system of predation, flight, and unjust luxury took hold—while the people starved and voices were silenced.

How can we understand the reign of Jean-Claude Duvalier—caught between dynastic continuity, authoritarian drift, and the commodification of a suffering people?

We explore it here through a triptych: childhood under portraits, a reign between indifference and brutality, and the memory of a return that never amounted to repentance.

The son of papa doc

Some legacies weigh heavier than crowns. In April 1971, Jean-Claude Duvalier, barely nineteen, inherited Haiti’s throne like a funeral. His father, François Duvalier, had prepared the succession with clinical precision, amending the Constitution to proclaim his son president for life. This transfer of power was more than politics—it marked the mutation of a postcolonial republic into a Black monarchy, where power passed not by merit but by blood.

Nicknamed “Baby Doc,” Jean-Claude lacked both experience and hunger for power. His rise to the presidency was seen by many as a tragic farce—a performance orchestrated by an elite eager to preserve its privileges. In a nation already scarred by decades of dictatorship, this dynastic succession felt like a betrayal of the Haitian Revolution’s ideals, an insult to the memory of those who had fought for freedom.

Jean-Claude Duvalier was not a statesman but a young man thrust unprepared onto the political stage. Rather than govern, he indulged in the pleasures of high society, leaving the reins of power to his mother, Simone Ovide Duvalier, and a clique of loyal Duvalierists. This delegation turned the state into a family business, where decisions served the private interests of the Duvalier clan—not the people.

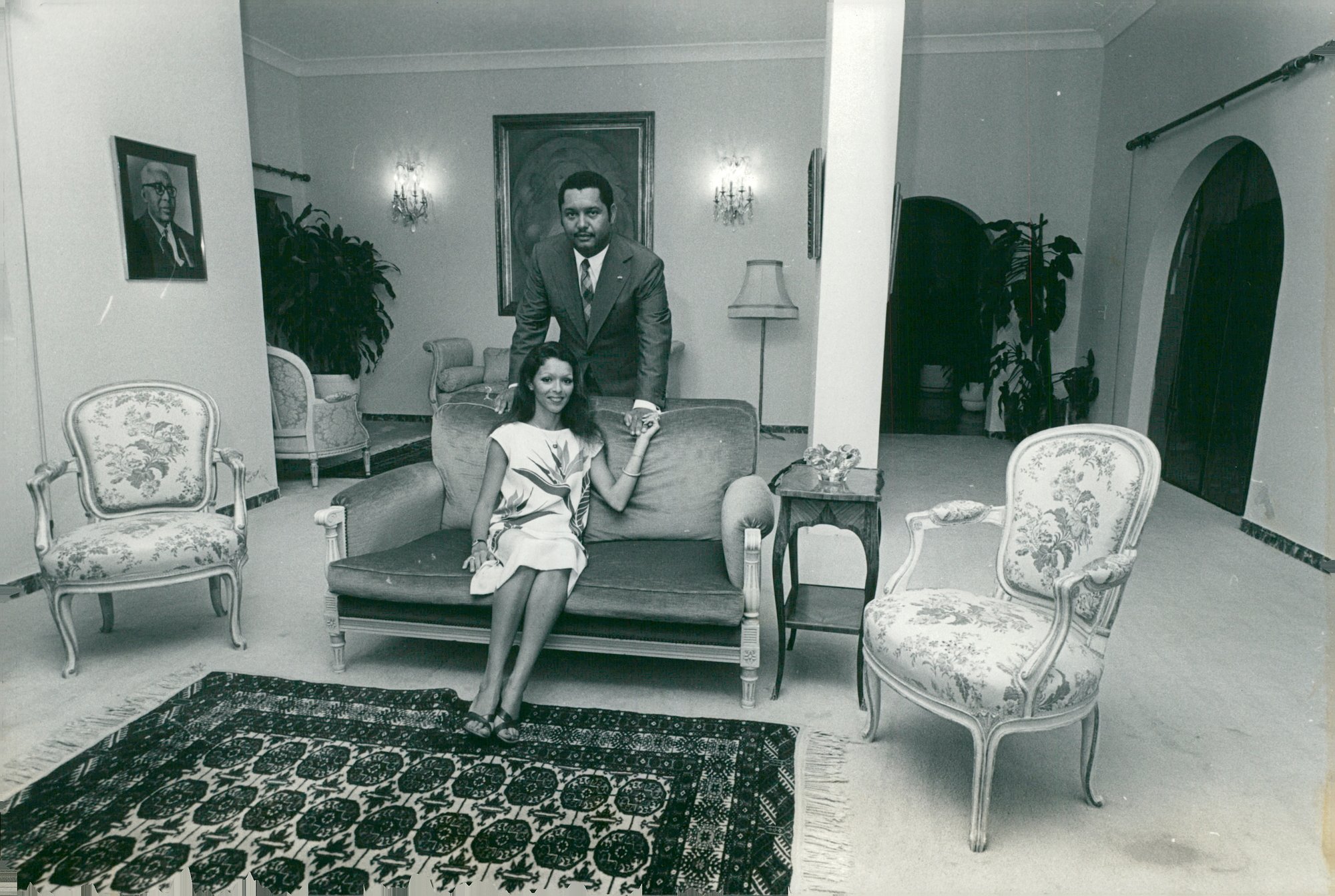

His 1980 marriage to Michèle Bennett, celebrated with obscene extravagance, symbolized the regime’s total disconnection from the Haitian people’s reality. While the majority lived in abject poverty, the presidential couple spent millions on a lavish ceremony. This ostentation only deepened popular resentment and laid bare the corruption rotting the state.

Under Jean-Claude Duvalier, terror became a tool of governance. The Tontons Macoutes, the paramilitary militia created by his father, continued to sow fear—arresting, torturing, and killing those who dared oppose the regime. This systematic violence created a pervasive climate of suspicion, where no one was safe, and fear became the glue of illegitimate power.

Prisons swelled with dissidents, forced exiles multiplied, and the press was muzzled. This brutal repression was not just a continuation of “Papa Doc’s” methods—it was an escalation of state violence used to compensate for “Baby Doc’s” lack of legitimacy and vision. In this republic of suspicion, silence became a survival strategy, and fear, a state policy.

The prince in inner exile

In Port-au-Prince, murmurs grew louder: how could the son of the Black doctor, heir to a Black nationalist ideology, marry a woman from the mulatto elite? Jean-Claude Duvalier’s marriage to Michèle Bennett in 1980, marked by indecent opulence, symbolized a rupture with his father’s political legacy. This was not just a union between two individuals—it was the fusion of two historically antagonistic worlds.

Michèle, the daughter of a wealthy businessman, brought with her the privileges and expectations of a class long marginalized by Duvalierism. Rather than reconcile Haiti’s racial and social divisions, the union deepened them—widening the gap between the rulers and the ruled.

While most Haitians struggled to survive, the presidential couple lived in excess. The National Palace became the scene of sumptuous parties, where guests were showered with expensive jewels and Jean-Claude dressed as a sultan, handing out gifts to mask the people’s suffering. The Bennetts expanded their businesses, engaging in activities from car dealerships to drug trafficking. This ostentatious wealth, in a nation plagued by endemic poverty, fed popular anger and symbolized a national betrayal.

Deprived of democratic legitimacy, Jean-Claude tried to buy affection by throwing wads of cash to crowds. But these acts only underscored his political emptiness. Institutions became instruments of repression, opposition was silenced, and elections became hollow rituals. The regime, cut off from the people’s reality, sank into stagnation—unable to meet a nation’s yearning for justice and dignity.

A dictatorship toppled by its specters

In the 1980s, Haiti was hit by crises that deepened public discontent. The AIDS epidemic stigmatized the country globally, crippling the fragile tourism economy. Simultaneously, the U.S.-backed Program for the Eradication of African Swine Fever (PEPPADEP) led to the mass slaughter of Creole pigs—a vital income source for Haitian peasants.

These policies, seen as direct assaults on traditional livelihoods, intensified rural rage. As misery deepened, the long-silenced people began to express their despair through protests and uprisings.

On March 9, 1983, Pope John Paul II visited Haiti and, before a crowd in Port-au-Prince, declared: “Things must change here.” This statement, widely viewed as a rebuke of Duvalier’s regime, electrified the public and heightened calls for political change.

The Catholic Church, once cautious, became a key player in civic awakening, urging the population to seek democracy and social justice. The Pope’s words acted as a catalyst—turning latent frustration into active resistance.

By the mid-1980s, international support for Duvalier waned. The Reagan administration, initially supportive due to Duvalier’s anti-communist stance, withdrew its backing as unrest intensified. In January 1986, the U.S. pressured Duvalier to step down, refusing him political asylum but offering assistance for his departure.

On February 7, 1986, Jean-Claude Duvalier handed power to a military junta and boarded a U.S. Air Force plane to France. His exit ended 28 years of Duvalierist rule. Yet the transition was chaotic—institutions were fragile, and the country entered a prolonged period of political instability.

Thus, Jean-Claude Duvalier’s fall was the result of converging factors: economic deterioration, lost international support, and a collective awakening inspired by moral voices. This historic moment showed how a people could overthrow an oppressive regime when internal and external conditions aligned for change.

Gilded exile, bitter return

When Jean-Claude Duvalier fled Haiti in 1986, he headed to France, carrying a fortune estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Though formally denied asylum, he benefited from diplomatic leniency, living comfortably in Paris for 25 years. This illustrates the paradox of a former colonial power offering silent refuge to a deposed dictator—never responding to extradition requests nor supporting Haitian justice efforts.

On January 16, 2011, Duvalier returned to Haiti, officially to “assist with reconstruction” after the devastating 2010 earthquake. However, the timing coincided with the February 1 implementation of the “Duvalier Law” in Switzerland, which facilitated the confiscation of illicit assets held by dictators. By returning, Duvalier seemed intent on proving he was not under prosecution in Haiti—hoping to reclaim $6.2 million frozen in Swiss accounts. This move revealed a strategy where justice was manipulated for personal financial gain.

On October 4, 2014, Jean-Claude Duvalier died of a heart attack in Pétion-Ville, never having faced trial for crimes against humanity. Despite the efforts of groups like the Collective Against Impunity—which filed charges for torture, enforced disappearances, and embezzlement—the Haitian justice system failed to bring him to court.

His funeral, private and without official recognition, left behind a wounded national memory and unfinished justice. The absence of a trial denied victims closure and reinforced a sense of impunity—further eroding Haiti’s rule of law.

The weight of the dead: What remains of duvalierism?

Jean-Claude Duvalier didn’t just rob a people—he buried their history in orchestrated amnesia. He is the archive of a century of betrayal, in which a Black ruler played the role of an internal colonizer. He left no legacy—only a void. And that gaping hole is the debt Haiti still pays—not in money, but in dignity.

Sources

- Abbott, Elizabeth. Haiti: The Duvaliers and Their Legacy. Paris: McGraw-Hill Editions, 1988.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Haiti, State Against Nation: The Impossible Justice. Port-au-Prince: Henri Deschamps Editions, 1996.

- Girard, Philippe R. Haiti: The Tumultuous History – From Pearl of the Caribbean to Broken Nation. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Schuller, Mark. Killing with Kindness: Haiti, International Aid, and NGOs. Rutgers University Press, 2012.

- INA Archives, documentary videos on Jean-Claude Duvalier’s departure, February 1986.

- Human Rights Watch. Reports on Crimes Against Humanity in Haiti (1971–1986).

Table of Contents

- Inheriting Silence, Ruling Over Cries

- The Son of Papa Doc

- The Prince in Inner Exile

- A Dictatorship Toppled by Its Specters

- Gilded Exile, Bitter Return

- The Weight of the Dead: What Remains of Duvalierism?

- Sources