Long before Auschwitz, another genocide unfolded in the scorching silence of the African desert. Between 1904 and 1908, colonial Germany methodically attempted to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples in Namibia. Concentration camps, medical experiments, deportations: it was the first industrialization of death in the 20th century.

Nofi traces the buried history of this tragedy, its ideological extensions up to Nazism, and the contemporary struggles for justice, remembrance, and reparations. A history Europe would rather forget—but Africa has never ceased to bear.

Where the sand carries the bones

The history of the Herero and Nama genocide does not begin with bullets. It begins with maps. With the oversized ambitions of a late-blooming empire—Wilhelmine Germany—arriving in Africa with compasses, bayonets, and a fantasy: that of a “new empire” colored in blood and ivory. In Namibia, German imperial arrogance met proud, deep-rooted peoples determined not to be erased.

But the lines drawn on paper soon turned into lines of fire in the Omaheke desert. The sand swallowed bodies, names, memories. History looked away.

For it was there, between 1904 and 1908, in this corner of German South West Africa, that a dress rehearsal took place for what the 20th century would multiply: bureaucratic extermination, racism turned science, the militarization of death. Long before Auschwitz, Europe learned to kill methodically—and it learned it here.

“This nation must be destroyed,” wrote General von Trotha.

“Or else forced to leave the country.”

—Order to the Herero, October 2, 1904, proclaimed before German troops

This was not just another massacre—it was a methodology. The prototype of a century of coming horrors.

To understand the genocide of the Herero and Nama is not to unearth an isolated tragedy. It is to lay bare the insides of a system. To trace the thread from Shark Island to the experimental camps of Buchenwald. To remember, finally, that colonial impunity is not dead—it has merely changed form.

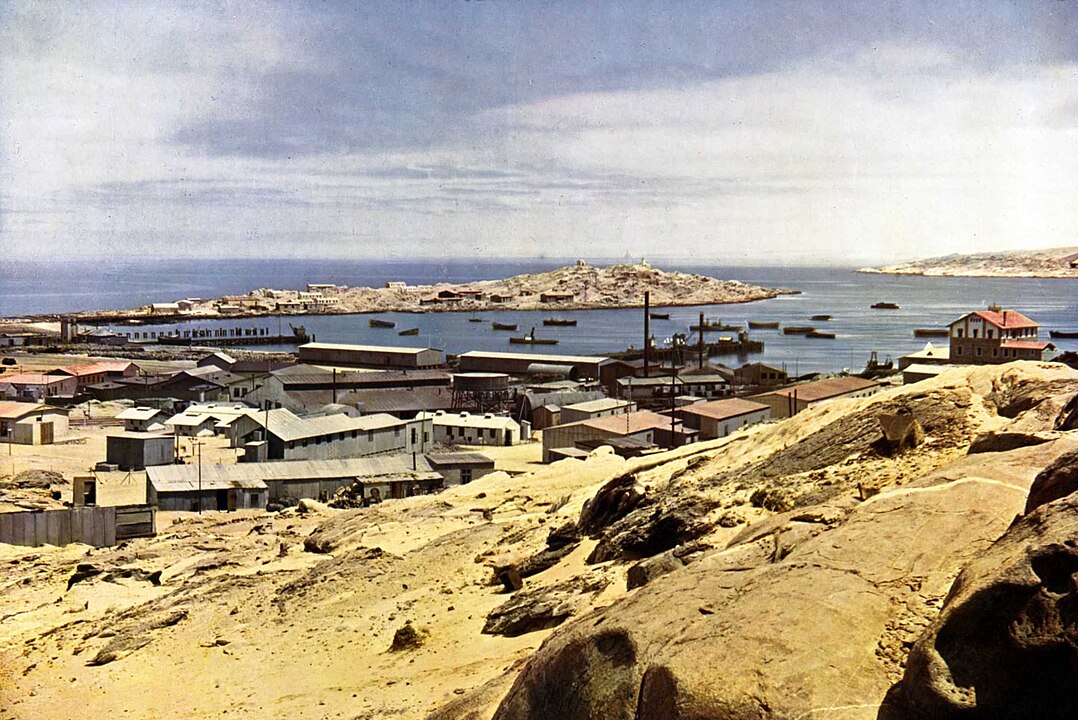

This time, Africa was not only the “laboratory of modernity”: it was its guinea pig. And in the silences of German history, in the erased ruins of Lüderitz and the forgotten skeletons of Omaheke, one can still hear the wind whisper a warning Europe refused to heed.

I. STOLEN LAND, IMPOSED SILENCE

(1884–1903: German Colonization and the Expropriation of Indigenous Peoples)

When the German Empire entered the colonial race in 1884, it was already late. Africa had been carved up in Berlin like a cake of ivory and rubber. Bismarck’s Germany still had no share. So it set its sights on a patch of desert: Namibia. At first glance, a dry, rocky land, scorched by Atlantic winds. But beneath this rugged soil lay what Europe saw as a “white future”: lands to exploit, peoples to dominate, and a blank page to inscribe in the grand imperial narrative.

To the Herero, this land was Otjiserandu. It was not empty. It was inhabited, cultivated, sacred. The Herero were pastoralists—proud and hierarchical—for whom cattle were more than wealth: they were living memory. Each cow had a name, a lineage, a place in the family’s history. The Nama, further south, were seasoned traders and herders, crossing the desert with their livestock and their stories. Two Black peoples, sovereign on their land. Two cultures the German Empire refused to see as anything other than obstacles.

From the first treaties, everything was falsified. In 1883, German trader Adolf Lüderitz bought a stretch of coastline with glass beads and rifles. The contract was rigged, the land value manipulated. But the Reich ratified it. In 1884, Germany officially declared a “protectorate” over South West Africa. That word—“protection”—in fact concealed a program of systematic dispossession. The land was “protected”… by being taken.

“The Herero did not offer us their lands.

We took them using white man’s tricks—and rifles when in doubt.”

—Confidential Schutztruppe report, 1892

In the following years, German settlers poured in, hungry for land and social ascent. In their suitcases: maps, cadastral registers, rifles, and racial certainty. They settled, claimed, demarcated. The Herero were pushed into arid zones. They were “concentrated” already. Cattle were seized over fabricated debts. Lands were redistributed to German colonial companies. When chiefs protested, new treaties were imposed—just as exploitative—or soldiers were dispatched.

But this was not only a conquest by force. It was a war of infrastructure. The colonial administration erected its offices where huts once stood. It laid military roads over cattle paths. It built train stations—not to connect—but to ship: men, goods, lives.

And behind this bureaucratic concrete, an ideology took root: scientific racism. In Germany, scholars measured African skulls and calculated inferiority. They spoke of a “servile race,” of “incurable negritude.” The colonist in Namibia was already the architect of an erasure he believed legitimate. The Black man, here, had no soul. He had a utility.

“What we are doing here is for the future of civilization.

Africa must learn discipline.”

—Letter from Governor Leutwein to Berlin, 1898

But the sand does not forget. Herero songs still speak of the rivers they were forbidden. Nama poems still recall the names they tried to erase. And in this great imposed silence, in this deceptive peace before the genocide, something accumulated. Something that refused to die.

Anger.

II. DETONATORS: HUMILIATION, RAPE, USURY, AND REVOLTS

(1903–1904: Resistance and the Outbreak of Uprisings)

This was no spontaneous uprising.

It was anger that had matured in silence, fed by the daily slaps, the invisible blows of a system designed to quietly break the colonized.

By 1903, colonial Namibia was saturated with “ordinary” violence: the Herero man was reduced to a laboring body, the Nama woman a sexual prey, the Black child a future servant. Justice saw only what the white gaze wished to see. The colonial court was a theater of injustice, where Germans were plaintiffs, judges, and executioners.

Forced labor. Habitual rape. No punishment. This was the triptych of humiliation. And at the center of this spiral, a name: Dietrich.

In January 1903, this German trader coldly shot a Herero woman—the wife of a chief’s son—after an attempted rape. He pleaded drunkenness. The white court acquitted him, citing “tropical fever” and a fit of madness. The sentence landed like yet another slap. But this time, the silence broke.

Governor Leutwein, aware of the risk of an explosion, appealed the judgment. A second trial took place. Dietrich was sentenced… to a few years in prison. A nod to formality—not to justice. In Hereroland, the message spread: “The white man can kill the Black woman and sleep in peace.”

“Do you have the right to shoot our women?”

—Question heard throughout Herero territory, January 1903

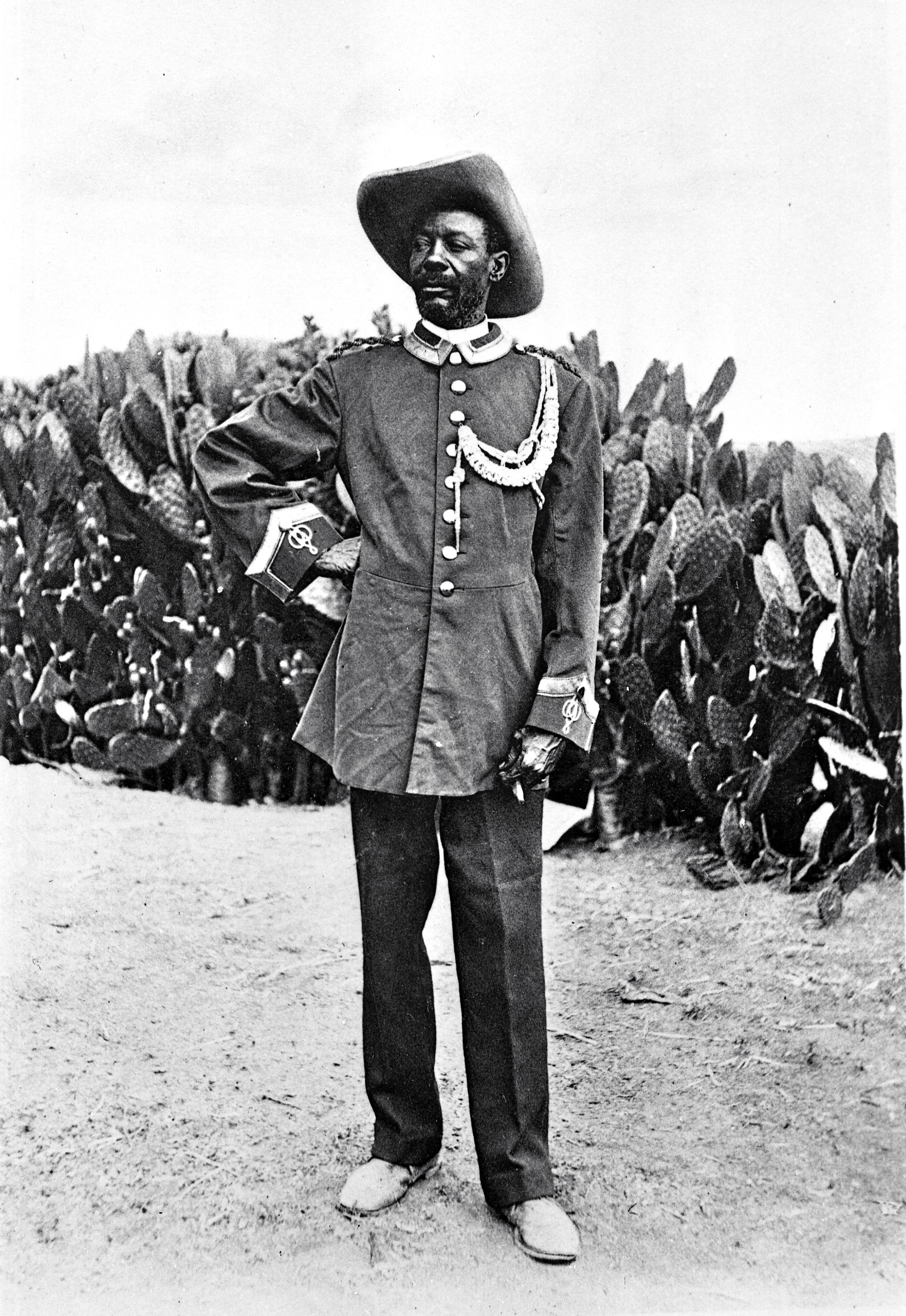

This is when the name of Samuel Maharero gained its full meaning. Son of Chief Maharero, raised between African traditions and European codes, he understood that the hope of compromise was dead. He gathered the clans, wrote to the Boers, the British, the Nama. And most of all, he called his people to dignity. For in the Herero worldview, humiliation is an insult to lineage. Noble blood must not be trampled.

AFurther south, Hendrik Witbooi—the white-bearded Nama chief—had already raised the banner of resistance. For years, he had fought the German colonizers in a guerrilla war marked by broken treaties and denounced betrayals. His journal, written in a mixture of prayer and rage, was a cry against European barbarity.

“What the white man calls civilization, we call dispossession.

What he calls faith, we call chains.”

While the chiefs gathered the embers, the people suffocated under pressure.

Debts exploded—usury, cattle seizures, land evictions. The railway sliced through traditional lands, heralding the reserves, the relocations, the enclosures. The settlers wanted more: more land, more labor, more obedience.

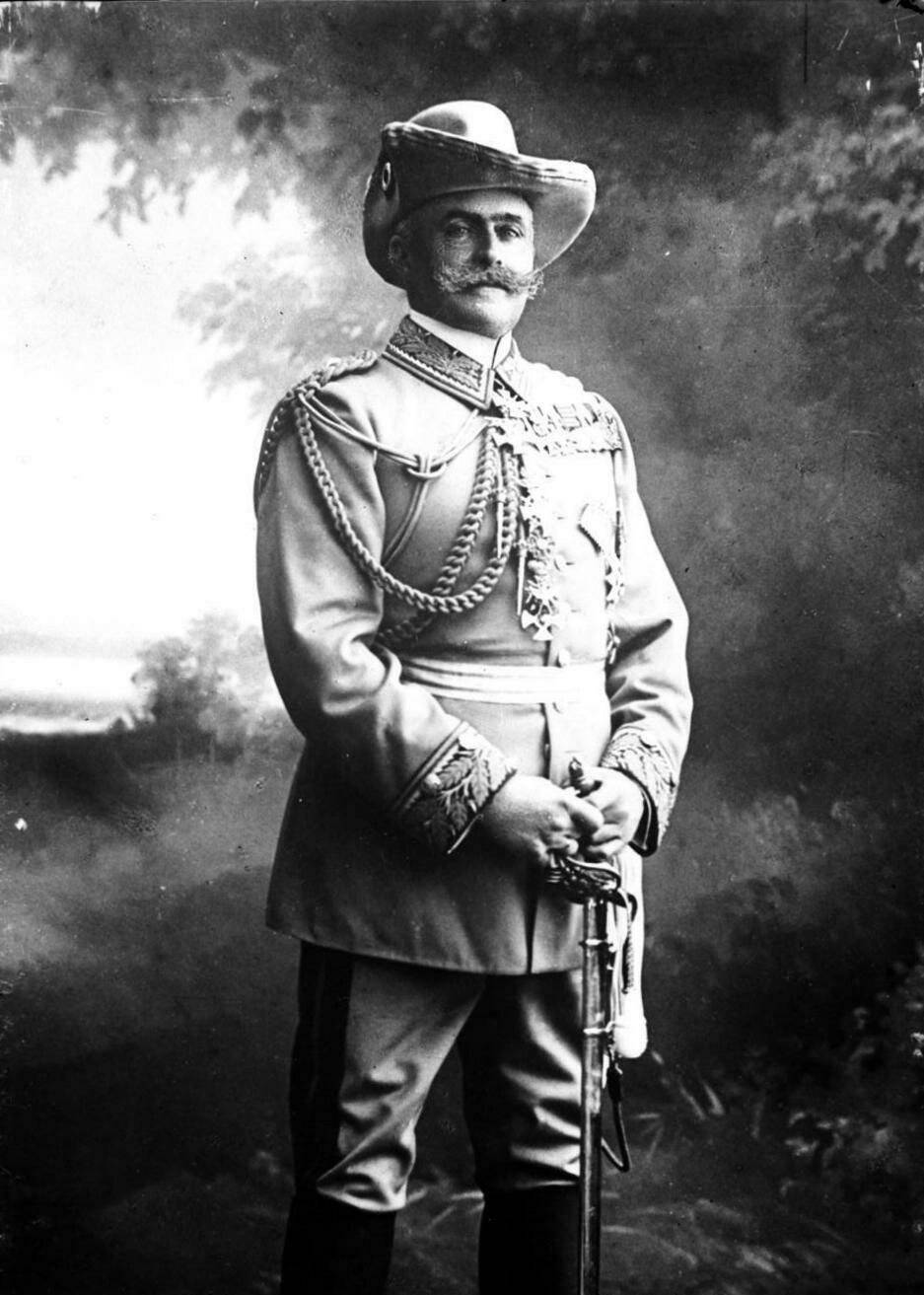

Governor Theodor Leutwein foresaw the catastrophe. Pragmatic, colonial but strategic, he wanted to negotiate, to buy time. He understood that Africa could not be ruled solely by the gun. But Berlin had other ambitions—and other men.

Portrait of General Lothar von Trotha, c. 1905.

The brutal military man, fresh from China, was already looming on the horizon. Where Leutwein sought appeasement, Trotha sought annihilation. He arrived with troops, orders, and racial theories.

In January 1904, the Herero acted. It was a targeted, organized attack: nearly 150 German settlers were killed. But Maharero strictly forbade harm to women, children, or missionaries. A code of war, even in revolt. A final gesture of humanity against a systemically inhuman regime.

But in Berlin, no one read manifestos. Only casualty reports.

The extermination machine was ready.

III. AN ORDER OF DEATH: VON TROTHA AND THE DOCTRINE OF EXTERMINATION

(1904–1905: From the Battlefield to the Desert of Erasure)

In the annals of modern horror, the Battle of Waterberg is less a battle than a trap—a colonial vise closed around a people fighting to survive. It was here, in August 1904, that the German army—10,000 men strong and steeped in contempt for Black life—launched its final operation against the Herero.

General Lothar von Trotha, recently arrived from China, was not there to negotiate. He came to execute an idea. His plan was not tactical, but ideological. He sought not surrender, but disappearance. Encircle, corner, starve—turn the desert into a weapon.

“I believe that the Herero nation must be annihilated.”

—Von Trotha, letter, July 1904

On August 11, German troops surrounded the Herero at Waterberg. The clash was brutal. But the annihilation failed: the Herero broke through the lines and fled east—into the Omaheke desert. A fatal error. For von Trotha awaited them there—not with cannons, but with the cruelest and most invisible weapon: thirst.

The wells were occupied or poisoned. Water points were guarded. The desert became a trap. German troops pursued the survivors—but mostly, they let the desert do the killing. They didn’t want to witness the deaths; they wanted to ensure the Herero never returned.

“They dug in the sand with bare hands to find water.

We found skeletons around deep pits—13 meters deep.”

—Report from a German officer

On October 2, 1904, von Trotha issued a public decree: any Herero found on German territory—armed or not, man, woman, or child—was to be executed.

No trial. No exception. A decree of ethnic death. The text was read aloud to soldiers. It was a genocidal proclamation in the strictest sense: it aimed to erase an entire nation from the territory, the landscape, and history.

“I no longer accept women or children.

I chase them away or shoot them.”

—Official proclamation to the Herero

The desert became an open-air cemetery. Up to 80% of the Herero population is estimated to have perished in a matter of months. Men without water. Pregnant women dead from exhaustion. Children abandoned under the scorching sun. The sand smothered the screams.

But beyond the tactics, it was the European racial imagination that was at work. Von Trotha was the product of an era where Africa was a blank slate to be filled with blood, where the Black man was a “natural obstacle.” The German Empire dreamed of an African “Wild West,” mirroring what the United States had done to Native Americans: drive them out, confine them, eliminate them.

German newspapers celebrated the victory. Sketches of “defeated savages” were published, grotesque caricatures circulated. In schools, the superiority of the German race was taught. In Berlin, scientists requested Herero skulls to study the “primitive African skull.” Africa became a white death laboratory, where ideas were tested that would later grow elsewhere, with higher numbers but the same logic: extermination.

“Only brute force impresses the Negro.

He does not understand treaties.”

—Von Trotha, military speech, 1904

Von Trotha was no lone monster. He was the executive arm of a system. He wrote to the Kaiser. He reported to the General Staff. He received decorations. And most importantly: he was never tried.

Because what Europe was testing here wasn’t just war—it was the feasibility of mass killing without consequence.

IV. CONCENTRATION CAMPS: SHARK ISLAND, FIRST INDUSTRIALIZATION OF DEATH

(1905–1908: Camps, Bones, and Numbers That Lie)

Before Auschwitz, there was Shark Island.

Before the sealed train cars, there were chains on the docks of Lüderitz.

Before the extermination bureaucracy, there were metal plaques etched with registration numbers, worn around the neck like state-inflicted scars.

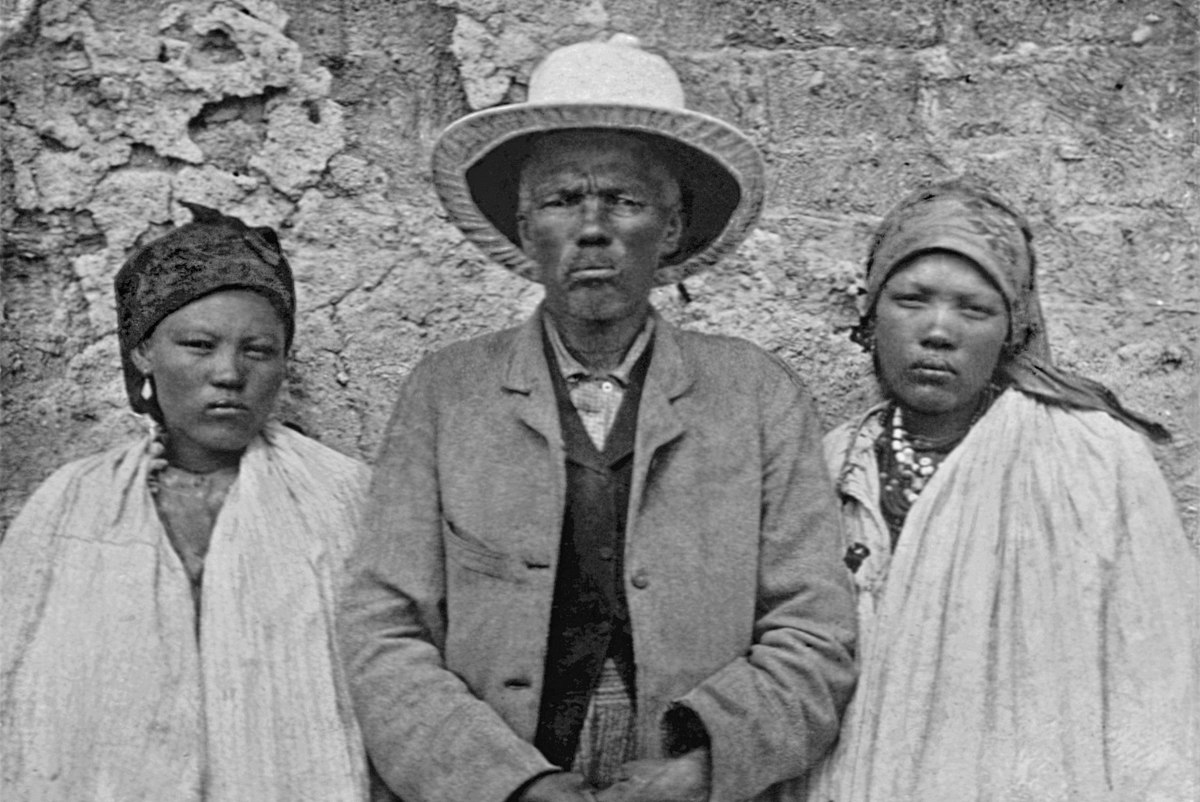

When the cannons fell silent in the Omaheke Desert, the surviving Herero and Nama—what little remained of them—were not rehabilitated. They were processed, dehumanized in assembly-line fashion. Shark Island, at the far southern tip of German Southwest Africa, off the coast of Lüderitz, became the most infamous of these camps. A barren islet battered by salt winds, devoid of trees, shelter, or mercy.

There, between 1905 and 1907, the German army inaugurated what amounted to the first modern death factory.

Prisoners were sorted. The able-bodied were sent to forced labor for settlers. The rest were abandoned. Bread was scarce. The water was brackish. Corpses piled up. Every day, the dead were buried at low tide—so the sea could wash them away.

“Hunger, cold, disease, madness—each night claimed its toll.

In the morning, we gathered the bodies.”

—Testimony of Fred Cornell, South African prospector, 1906

Official figures claim mortality rates of 45% to 74%, depending on the camp. But those numbers lie. They count deaths, not destroyed souls. They omit dissected bodies, skulls shipped to Berlin, women turned into sex slaves or lab specimens.

The testimonies are chilling. A woman, carrying her child on her back, collapses under a sack of grain. A German soldier beats her with a sjambok—a leather whip. He hits the baby too. Without a word. Just an order. A habit.

“Prisoners are treated like sick cattle.

They fall, they are beaten.

They die, they are replaced.”

—Missionary report, 1905

Nama women in particular endured specific abuses: some were raped by guards. Others were used in medical experiments:

injections of toxic substances, “live” specimen removal, fetal dissection.

Colonial doctor Dr. Bofinger injected arsenic and opium into the sick before dissecting them “for study.”

Meanwhile, in Berlin, German universities received boxes.

Skulls. Organs. Femurs.

They were cataloged, measured, classified. They fed the eugenic theses of scientists like Eugen Fischer, future mentor of Mengele. Africa became a racial laboratory, and Shark Island its center of experimentation.

“I gladly harvest from fresh cadavers.

It enriches my studies on negroid physiology.”

—Leonhard Schultze, German zoologist

In this apparatus, death was not an end—it was raw material.

A resource. An object of study.

And what was tested on the Herero and Nama at Shark Island wasn’t only poison—it was technique. Methods. Thresholds of acceptability. It was the industrialization of the inhuman.

The survivors were never given a mausoleum. Their bones still bleach in the dunes, forgotten by law, ignored by history. Only decades later would human remains—numbered skulls—be exhumed from the storage rooms of German universities.

Some still bore the camp’s markings. For Shark Island was not an accident.

It was a prototype.

V. SCIENCE AS A WEAPON: MEDICINE, EUGENICS, AND THE FORESHADOWING OF NAZISM

(1905–1910: from black skulls to Aryan Theory)

Colonial Europe did not kill only with the sword. It killed with the scalpel.

At Shark Island, the bodies of Herero and Nama victims were not only thrown into the sea or buried in the sand. They were exhumed, dissected, and shipped off. For behind every military operation, there was another, quieter, colder front: that of racial science.

Between 1905 and 1910, hundreds of skulls and human bones were sent from German South West Africa to Berlin, Freiburg, and Jena. Most came from prisoners who died in the camps. Their heads were boiled, scraped of flesh, bleached, numbered, and carefully packaged. These were called “study materials.”

“It was a shipment of skulls for science.

But more than that, it was a burial without prayer.

A stripping of dignity.”

Among the beneficiaries of these macabre parcels: Eugen Fischer, a biologist who studied these remains in his Berlin laboratory. He developed theories about “racial degeneration” and the “genetic inferiority of Black blood.” For Fischer, mixed-race children born of relationships between German men and Herero or Nama women were anomalies to be eradicated. He advocated the sterilization of mixed-race people. He labeled them “unfit for civilization.”

“Miscegenation is a poison to the soul of the people.”

—Eugen Fischer, Principles of Racial Biology, 1913

Fischer was not a footnote in history. He became rector of the University of Berlin. He taught Otmar von Verschuer, who later mentored Josef Mengele—the angel of death at Auschwitz. The chain is clear. From Shark Island to Auschwitz, the link is not just symbolic. It is intellectual, methodological, institutional.

Other German scientists like Leonhard Schultze, present on-site, wrote unashamedly in their research journals:

“I harvested pieces from fresh cadavers.

It was a welcome enrichment for my studies of negroid physiology.”

The Black body became a field of experimentation. A surface. An object.

The camp became a clinic. The anthropologist, a gravedigger.

But this science did not evolve in a vacuum. It infiltrated political discourse. It seeped into schools, journals, the halls of power. No longer was the Black person merely killed with bullets—they were defined as biologically superfluous, as genetic threats, as Darwinian obstacles. This shift—from hatred to scalpel, from battlefield to lab—was the beating heart of European eugenics.

“What was done in Namibia was not an aberration.

It was a test. A first version.”

And if history remembers the name Mengele, it often forgets that his hypotheses were first tested on the Herero. That the first to be measured, sterilized, classified, and dissected were not the Jews of Europe—but captive Africans who died in silence.

In German museums, the numbered skulls remained for over a century.

They weren’t hidden. They were ignored.

This too is postcolonial violence: when crime becomes archive, and archive becomes oblivion.

VI. WHAT EUROPE CHOSE TO FORGET

(1908–1990: Post-Genocide, Imperial Silence, Confiscated Memory)

After the horror, there was no trial, no mourning.

No commission to bring the truth to light.

No statues for the dead.

There was only sand—and silence.

In 1908, the German Empire closed the blood-soaked chapter of its colonial war. The word genocide didn’t yet exist, but the intent—and its consequences—were unmistakable. What the surviving Herero and Nama found upon their return was not peace, but a colonial society restructured around their submission.

Most were reduced to forced labor. Men wore metal ID tags around their necks. Women, often raped and stigmatized, could no longer raise their children in their native languages. Children were sent to “educational” institutions where they were taught to serve, to stay silent, to forget.

The Herero were forbidden from owning land or cattle—an effective cultural amputation for a pastoralist society. Their world, built on inheritance, herds, and ancestors, was methodically dismantled. They now lived on lands borrowed from their former executioners. Settlers built homes where their dead lay buried.

“The conquest was done.

What remained was to build amnesia.”

And while the bodies faded into the dunes, German settlers raised their monuments. In Windhoek, the colonial capital, a bronze statue was erected in 1912: the Reiterdenkmal, an imperial rider celebrating German soldiers who died “for civilization.” Not a word for the tens of thousands of massacred Africans. Not a stone for Samuel Maharero, nor for the mothers who died on Shark Island.

In Reich schools, the genocide was never mentioned. In Berlin, it was called a “forceful campaign.” In Paris and London, eyes were averted. The West remained silent—because to accuse Germany was to risk shedding light on its own colonial crimes.

And yet, the colony lived on. After Germany’s defeat in 1915, South Africa took over the territory under a League of Nations mandate. A new master, the same contempt. Apartheid was not yet named—but already in place. Racial laws, forbidden zones, skin hierarchies; all were established. Colonial continuity was guaranteed: Black skin remained a crime, Black blood a flaw.

“History is not written by the victors.

It is written by those who stay behind to build the statues.”

For decades, archives were sealed. Bones were shelved. Memories were silenced.

The Herero and Nama passed on their pain orally—in songs, in silences.

A hollow memory passed from grandmother to grandson, like embers beneath ash.

Europe chose useful forgetting. Profitable forgetting.

Only at the turn of the 21st century were the first skulls returned.

Only in 2004 did a German minister stand in Okakarara and say the word “responsibility.”

And only in 2021 was an official agreement signed, finally using the word “genocide.”

But by then, nearly a century had passed.

And silence had done more damage than any cannon.

VII. HEIRS OF THE UNSPEAKABLE: STRUGGLES FOR TRUTH AND JUSTICE

(1990–2021: From Late Apologies to the Fight for Reparations)

Sand may not keep footprints—but people remember.

After Namibia’s independence in 1990, the Herero and Nama spoke again where their ancestors had been silenced.

Though their bodies had been scattered, memory remained alive—stubborn, intact, outraged.

From the 1990s, Herero community leaders like Zed Ngavirue publicly revived the call for reparations. Petitions were filed with the UN. In 2001, the Herero People’s Reparation Corporation filed a lawsuit in the United States, demanding $4 billion in reparations from the German government and companies that profited from colonialism—such as Deutsche Bank and Terex.

But the case failed. Sovereign immunity was invoked. Once again, the West looked away.

Yet a precedent had been set.

For the first time, an African people had tried to use international law to have a colonial crime recognized as a crime against humanity.

In 2011, then in 2018, Germany returned several dozen Herero and Nama skulls stored in Berlin museums. A ceremony was held, speeches were made.

But descendants denounced a performance of memory—a spectacle without real substance, with no official apology and no compensation.

“They return bones—not accountability.”

—Herero Descendants Association

The gesture was symbolic—but the conditions of the return (no identification, no legitimate representatives at the ceremonies) sparked anger.

To many, it was not an act of reparation—but a PR campaign: a display of remorse without accepting consequences.

In May 2021, after five years of bilateral negotiations, Germany announced a historic agreement: official recognition of the Herero and Nama genocide, and a pledge of €1.1 billion in aid over thirty years. But the money would not go to the communities affected—it would go to the Namibian state, as development aid.

No direct reparations. No individual compensation. No presidential apology to descendants.

“We were killed without justice.

Now our pain is being negotiated without us.”

—Veronica Katjirua, Herero traditional leader

Outrage swelled. Nama and Herero leaders denounced a deal made without consultation—negotiated between states and excluding the heirs of genocide. In Windhoek, protests erupted. In Berlin, organizations condemned the agreement as neocolonial.

Germany’s gesture, hailed as a “historic step,” was locally perceived as a slap disguised as a handshake.

The struggle continues. In courts. In memory. In symbols.

The genocide of the Herero and Nama is now recognized by many historians as the first genocide of the 20th century.

But it still has not led to any international judicial proceedings.

And if reparations ever arrive, they will face a wall: the global system built on colonial impunity.

But the descendants—they have not forgotten.

VIII. FROM THE DESERT TO AUSCHWITZ: GENOCIDES HAVE A HISTORY

(Genealogy of Horror: Continuities Between Colonial Africa and the Shoah)

“Auschwitz didn’t fall from the sky.”

—Achille Mbembe

The Cameroonian philosopher’s words resonate like a warning.

For the horrors of the 20th century did not erupt from nowhere.

They have roots. They have drafts.

And among them, the genocide of the Herero and Nama stands as a silent template.

Since the 2000s, historians, sociologists, and philosophers have debated:

Should we see the 1904–1908 massacres as a precursor to the Shoah?

The question divides.

Some, like Jürgen Zimmerer or Mahmood Mamdani, speak of a colonial continuum—a logical link between imperial racism and Nazi racism.

Others fear anachronism, worrying that the uniqueness of the Shoah might be diluted by such comparisons.

But the terrain does not lie.

At Shark Island, long before Auschwitz or Treblinka, Germany tested rationalized killing, racial classification, the logic of “useful” extermination.

The Herero and Nama were the first described as “biological surplus.”

The first to be interned in camps run by registries, identified with plaques, sorted by productive value.

It’s not the number of dead that links the two genocides.

It’s the ideological machinery, the language of calculated elimination, the bureaucratic indifference to inhumanity.

“The mixed-race person is a threat to the German race.

He must be neutralized.”

—Eugen Fischer, 1908

Thirty years later, the same concepts—racial purity, contamination, degeneration—would guide the Nuremberg Laws, forced sterilization programs, and ultimately, the Final Solution.

The link is not merely theoretical. It is institutional: Eugen Fischer mentored Josef Mengele.

The ideas tested on Black bodies fed the dogmas applied to Jewish, Roma, or Slavic bodies.

More broadly, it was colonial dehumanization that prepared European public opinion to accept extermination.

For centuries, Africans were portrayed as sub-human, as beings outside the law.

What Europe accepted for Blacks in Africa (camps, massacres, sterilization, racial measurement), it would later reproduce on its own soil, against those it now labeled “internal enemies.”

“Colonial empires were the laboratories of the modern world.”

Thus, the history of genocides cannot be written in isolated compartments.

It is not made of absolute ruptures, but of slides, rehearsals, and repetitions.

And if the Shoah is unique in its scale, it did not arise from a moral vacuum.

It was the fruit of a century of rationalized hate, legitimized domination, and unpunished crimes.

To recall its shadows is not to diminish the Holocaust—but to place it within the long history of contempt for the Other.

SPEAK THEIR NAMES, SO THEY MAY LIVE

More than a century has passed, and still the footsteps of the Herero and Nama echo through Namibia’s red valleys.

No longer fleeing.

But bearing witness.

Every year, they march.

In period uniforms, in traditional dress, in silence.

They walk upon the land where their ancestors were hunted, parched, scorched by sun and bullets.

They march to remind the world that memory has no expiration date.

That the dead still cry to be named, to be returned, to be cleansed of oblivion.

Because this is not only about history.

It is about delayed justice, unearthed truth, blocked reparations.

It is about what the world does—or does not do—when entire peoples are wiped out, then erased from textbooks.

This genocide was first perpetrated by Europe.

Then denied.

Then buried in the dust of its archives.

Even today, it is taught in only a handful of schools.

Absent from memorials.

Unmarked by any holiday.

Yet it was in Africa that the 20th century first learned to kill methodically.

So what now, now that we know?

What do we do—while elsewhere, other peoples still fall to the bullets of impunity?

While other children are still dehumanized, other lands stolen in the name of “order,” other memories erased by diplomatic silence?

We have a duty.

A name.

A legacy.

To recite, one by one, the names History tried to erase.

To make heard, across centuries, the cry rising from the Omaheke desert to the walls of Auschwitz—to today’s camps—to slumbering consciences.

Because the dead do not ask for tears.

They ask to be heard.

And through them, that no one ever again be killed in the shadows.

FURTHER READING TO UNDERSTAND

- Jürgen Zimmerer & Joachim Zeller, L’Empire colonial allemand : crimes oubliés, Autrement, 2013.

- Benjamin Madley, From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe, European History Quarterly, 2005.

- Jan-Bart Gewald, Herero Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia, James Currey, 1999.

- Eugen Fischer, Die Rehobother Bastards und das Bastardierungsproblem beim Menschen, Jena, 1913.

- Pascal Blanchard, Nicolas Bancel, Sandrine Lemaire (eds.), La fracture coloniale, La Découverte, 2005.

- George Steinmetz, The Devil’s Handwriting, University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Elizabeth Baer, The Genocidal Gaze, Wayne State University Press, 2017.

- Henning Melber, Germany and Namibia: Negotiating the Past, Africa Spectrum, 2017.

- Memory Biwa & Reinhart Kössler, The Settler Colonial Present, The South Atlantic Quarterly, 2012.

- Podcast: The History of the Herero and Nama Genocide, DW, 2021.

- Documentary: Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich, BBC Four, 2004.

Table of contents

Where the Sand Carries the Bones

I. STOLEN LAND, IMPOSED SILENCE

II. DETONATORS: HUMILIATION, RAPE, USURY, AND REVOLTS

III. AN ORDER OF DEATH: VON TROTHA AND THE DOCTRINE OF EXTERMINATION

IV. CONCENTRATION CAMPS: SHARK ISLAND, FIRST INDUSTRIALIZATION OF DEATH

V. SCIENCE AS A WEAPON: MEDICINE, EUGENICS, AND THE FORESHADOWING OF NAZISM

VI. WHAT EUROPE CHOSE TO FORGET

VII. HEIRS OF THE UNSPEAKABLE: STRUGGLES FOR TRUTH AND JUSTICE

VIII. FROM THE DESERT TO AUSCHWITZ: GENOCIDES HAVE A HISTORY

Recite Their Names, So They May Live

Further Reading to Understand